| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2019 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

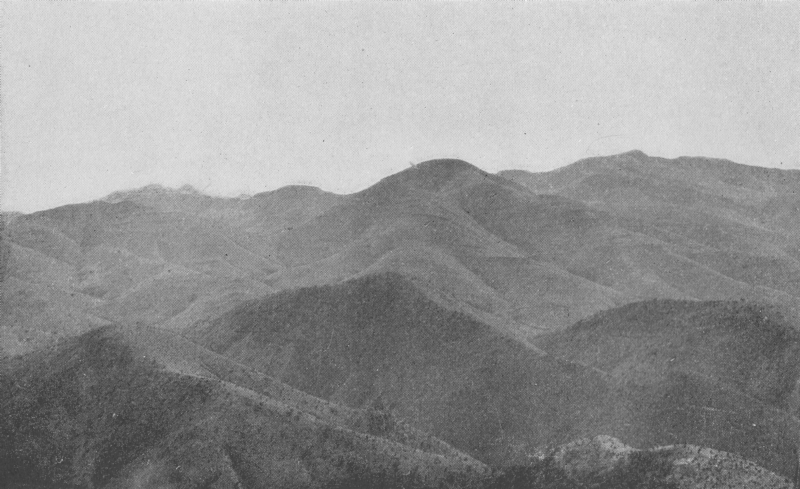

Round

about Bisbee. ALTHOUGH I had been for some days sightseeing from a car-window in New Mexico, and had had more than one good stroll over desert-like prairies, I was not so forcibly impressed with the fact that I was in the far West as when I reached this wonderful Arizona mining region. Then the country back of me was indeed “on East," and I was at last “out West." Of Bisbee itself there is little to be said. It is gathered together in a little valley, hidden by high hills, and presents no striking feature, as seen from the station, when you leave the cars, or later, as you pass along its single street. The little adobe houses perched upon the hill-sides, however, are somewhat picturesque, and, what is of more importance, very comfortable. It was then — late in July — the rainy season, and from noon until about sunset the rain is likely to be violent; but during the early morning one may wander over the hills and along the valleys without fear of a wetting. What had I in view in coming here? was the tiresome question that every miner asked as opportunity afforded; and when assured that it was merely to see new sights and a new country, an expression of doubt was plainly depicted on their countenances. They believed it was not merely to see a new flower or hear a new bird that brought me here. But it was: and now what of the sights and sounds round about Bisbee? Upon arrival I did not plunge in medias res, but looked upon the summits of the highest hills as inaccessible, and revelled in what I called mountain-climbing by scrambling over the near-by rocks. This tested my strength, gave me practice, added to my surefootedness, and so the day of a steep ascent found me equal to the task. We were off by 5 A.M., three of us, with a burro to carry our traps and a small boy to coax the patient donkey over the rocky trail. Our purpose was twofold: to reach the summit, and take photographs of such objects as struck our fancy. We succeeded admirably. There was not one familiar feature about or above us from the very start, for even the air and sky were strangely clear, and a soaring eagle that kept long in view seemed almost within gunshot, although circling far above an adjoining mountain; and later, when, following a swift-descending swoop, its impatient scream came floating earthward, we stopped as if the bird was threatening us. So it was that at the very outset the scales dropped from our eyes and our ears were quickened to novel sounds. But no new sound, as a bird's song, is so sure to attract attention as some one that has the subtle charm of association. A curved-billed thrush across the wide valley commenced singing, and at once the mountains vanished. How long I stood in the cool shadow of a thrifty oak I cannot tell, but when from a misty cloud the mountains reappeared, I was quite alone. I had been wandering under the homestead oaks, and for long after their misty outlines stood against the sky. If a clear atmosphere and high altitude sharpens one's wits, it may, too, overstrain the nerves and lead to many a blunder, particularly if the spirit of adventure is well upon one. I was in such a plight, and strange indeed if something should not befall me before I joined my party! As I was trudging along alone, every pebble rattling beneath my tread, I fancied some strange creature in my path. Not a crooked stick but suggested a serpent; and so, guarding against imagined dangers, I finally met with a real one: I sat upon a cactus. As a cure for unbridled imagination, I commend it. To better nurse my countless trivial wounds, I chose a rock for a resting-place, and considered the innumerable fragments of flinty stone that covered the entire hill-side. If color has aught to do with it, I was leaving behind me most tempting specimens of minerals. At almost every step I had been rolling down the hill crystals of many a hue, and dull-colored stone made beautiful by the green, blue, and crimson incrustations that covered them. Many a bit that I picked up and flung away was varied as the rainbow. But, beautiful as were all these, they paled to utter insignificance when brought in contact with the masses from the heart of the mountain. If one would know how magnificent a mineral may be, how it surpasses even the orchids among flowers, the butterflies among insects, or birds of paradise among birds, let him gather from the mouth of the great copper-mine fragments of the ore as they are ruthlessly dumped upon the ground. When malachite, azurite, and cuprite are seen as I saw them at Bisbee, then one can form some idea of Nature's perfected handiwork. If in the earth's unexplored regions there is awaiting man's coming some yet more magnificent exhibition than the play of sunlight upon clustered crystals, as I found them here, then man should have other senses whereby to appreciate it. Resuming my journey, I soon overtook my companions, and long before noon reached the summit. It was but a mass of loose, angular rocks, no larger than those that covered the mountain-side, nor more weather-beaten, although it is at such a spot that the clouds literally burst and spend their pent-up fury. This thought in mind, I was surprised to find, scattered between rock-masses, gray-green, brittle ferns, and one bright, ruddy flower, akin in appearance to our brilliant “painted cup" of the Jersey hills. How they could withstand the fury of the storms that rage thereabout, let some philosopher explain. Insignificant as was the vegetation here, it was equal to the task of holding desolation at bay, and no gloomy thoughts arose as we stood overlooking miles and miles of country. We were perched well aloft, surely, but as a mere speck overhead still floated the eagle that we had seen early in the day. It was a thrilling fancy that the eagle above us might be looking over the Pacific, and, with scarcely an effort, might turn eastward and be over our New Jersey home before we could reach the village at our feet. It was a merit of this day that rapid transit was the rule in all things, and we were never shocked by sudden transition from fancy to fact. From the soaring eagle to the broad-tailed humming-bird was a not unpleasant change, as I had never before seen a living species of this family except the familiar ruby-throat. It came and went, as such birds always do, without our knowledge of the direction it took, and promised to be quite uninteresting, until at last it spied our dog, and then its ire was excited. With an angry, bee-like whiz it darted to and fro, never actually touching the dog, but very loud in its threatenings as to the constantly-postponed next time. It seemed a more cowardly bird than the Eastern ruby-throat, which makes good its threats, and has been known to strike first and threaten afterwards. Fear of man seemed characteristic of a great deal of the animal life met with on the mountain, and I was not prepared to cope with this difficulty, having expected to find even the birds comparatively tame. Certainly the creatures that still linger in these now treeless mountains are seldom molested, and yet they all were more difficult to approach than allied forms at home. I realized this when a shining-crested flycatcher, that, as I saw it, looked like a black cedar-bird, came within fifty feet, and would permit of no nearer approach. But, thanks to the clear air, where nothing obstructs the sound, and vision is surprisingly acute, I could both see and hear this curious bird with some satisfaction. Its song is very sweet, yet I did not hear the full range of its melody, as one does who meets the bird during the nesting season. As to the wrens, they were not so bold as the little, brown fellows at home; and so through the whole list of animated nature. Herein lay the one disappointing feature of my mountain-climb. Over-anxiety for my neck caused my thoughts to centre in my heels on the return, and I saw surprisingly little; so consoled myself with the thought that what my first mountain failed to yield might be the special gift of an adjoining hill; and so it proved. But to spend hours on a mountain and come back with but one poor weed was too much for the patience of the miners, and I was truly pitied. For once, if not oftener, they had found an unquestionable crank. Very likely. But, then, if a man is not mildly a crank in some one direction, is he not sure to be a nonentity in all? |