| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2008 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

CHAPTER III THE EXQUISITE FURNITURE OF DUNCAN PHYFE SO far as I have been able to discover there are not many more than one hundred pieces of genuine Duncan Phyfe furniture to be found in museums or private collections to-day. It is a great pity, for Americans ought to know more about the work of this New York cabinet-maker of a hundred years ago. Most of the books on furniture either fail to mention Phyfe or dismiss him with a few words as one of the many followers of Sheraton. He was much more than that, for while he owed much to his English contemporary he developed a style of his own an American style, mark you and the best of his work is equal to anything ever produced by Sheraton or Hepplewhite. I think I am not overestimating him. An examination of such pieces as are to be found in the collection of Mr. R. T. Haines Halsey of New York cannot fail to awaken an enthusiastic admiration for the exquisite feeling for line, color, and detail which animated the work of this post-Revolutionary craftsman. Fortunately, however, there are now signs of a Phyfe revival. Since the exhibits at the Metropolitan Museum of Art during the Hudson-Fulton Celebration in 1909, the name of Phyfe has become more or less familiar to people who never heard it before. On Twenty-sixth Street, New York, just east of Third Avenue, there is a dusty, crowded little shop where fine reproductions of old furniture are made by two men named Hagen, who learned their trade from their father, Ernest Hagen, lately deceased, who was an inspired craftsman of the old school. It is not my purpose to advertise a modern cabinet-making business, but if it had not been for the unencouraged persistence and artistic enthusiasm of Mr. Hagen the elder, it is likely that we should be ignorant of the little we now know about Duncan Phyfe. Mr. Hagen followed every clue, interviewed every surviving relative, and before he died set down his discoveries in a notebook which, through the courtesy of Mr. Halsey, is now before me. While I have been able to obtain some additional information about Phyfe and his work, I think I cannot do better than quote at some length from Mr. Hagen's notebook. "In 1783 or 1784," he writes, "just after the close of the Revolutionary War, a Scotch family by the name of Phyfe left their home at Loch Fannich, thirty miles northwest of Inverness, with six or eight children, of whom two died on the long voyage in the old, slow sailing vessel. Coming here they settled in or near Albany, New York. "The second oldest son, Duncan, then about sixteen years old, learned the cabinet-maker's trade in Albany, and after a time set up a shop for himself. But he could not find work enough to make it pay in Albany, so he moved to New York and started business in Broad Street where most of the cabinet makers were then located. He got some work from Mrs. Langdon, the daughter of John Jacob Astor, which, done to her satisfaction, got him more orders. But after all it was not enough, and he concluded that he would go back to Albany and try it there a second time. When Mrs. Langdon heard of this she persuaded him to stay here and promised to help him wherever she could and recommend him to her friends. "He remained in New York, and after several moves finally settled at 35 Partition Street, which is now that part of Fulton Street lying west of Broadway, East Fulton Street being then called Fair Street. This was in 1795. In 1816 the name of the street was changed to Fulton and the houses were renumbered, his number being 192 and 194 with his dwelling house opposite at 193. "In 1837 the firm's name changed to Duncan Phyfe & Sons. In 1840 it again changed to Duncan Phyfe & Son, the son's name being James D. Phyfe. In 1847 he sold out and retired, but still lived at 193 Fulton Street until his death, which occurred August 16, 1854, in the eighty-sixth year of his age. He was buried in the family vault in Greenwood Cemetery, Brooklyn. His wife Rachel (nιe Salde or Salade) was born in Holland and died July 17, 1851. "Duncan

Phyfe's chief merit lies in the carrying out and especially improving

of the Sheraton style of settees, chairs, and tables in his best

period. The work about 1820, although the workmanship was perfect,

gradually degenerated in style, at first to the questionable American

Empire, and after 1830 to the heavy and nondescript veneered style of

the time when the cholera first appeared in New York. From 1833 to

1840 or 1845 the overdecorated and carved rosewood style set in which

Phyfe himself called 'butcher furniture.'

"Phyfe's shop stood at the west corner of Church Street. This whole block is now being pulled down [1907] to make room for the new tunnel to Jersey City. The site of his house opposite is now occupied by the Fire Department as an engine house. "Within a stone's throw of the old shop, in the sexton's office of St. Paul's Church, is one of Phyfe's sofas. Two chairs which they had to match it were lost. "Duncan Phyfe of Jersey City, now ninety-three years old [since deceased], who knows more about the old affairs than any of the other members of the family, says that his uncle was a very plain man, always working and always smoking a short pipe. In 1842 a Lord John Hays visited his shop to get some information concerning cabinet woods, when he would not even take the pipe out of his mouth. He was very strict in his habits and all the members of the family had to be in bed by nine o'clock. After retiring from business he kept on working at the bench making small things for his folks which they still preserve. . . ." Duncan Phyfe is described by his grandson as a small man of slight build. He was a member of the Brick Presbyterian Church and a very strict Calvinist. The more austere tenets of his faith had the effect of making his latter years somewhat gloomy. He was married young and had four sons and three daughters, the eldest daughter being named Isabella after the sister who had died at sea. For this daughter he built and furnished a commodious mansion at New Market, New Jersey, which is now occupied by his great-grandson, Mr. F. P. Vail. Mr. Vail, by the way, owns several excellent examples of Duncan Phyfe furniture, particularly of the Empire period. He also treasures a silver tea service which Phyfe designed, had executed in New York, and presented to his wife at the close of the War of 1812. Mrs. Vail is authority for the statement that the name was spelled Fife or Fyfe in Scotland, but that the family changed it for business reasons after settling here. At least one of Phyfe's brothers Lockland was associated with him in business, while John Phyfe was a grocer at 30 Barclay Street. After 1820 the names of several Phyfes appear in the directories, perhaps sons and nephews of the cabinet-maker. There was James A. Phyfe, a cabinet-maker on James Street; James, a carver, at 30 Barclay Street; John, Jr., ivory turner, 30 Barclay Street; Michael, cabinet-maker, 38 Dey Street. The Hudson Terminal Building now stands on the site of Duncan Phyfe's shop. His name and trade appear in the New York Directory of 1802 the only Phyfe in the book with the Partition Street address. When the name of the street was changed to Fulton in 1816, Phyfe's numbers were at first 168-172, with his house at 169; thus he appears in the 1821 directory. The numbers were changed to 194-196 and 193 about 1826. It is recorded that Phyfe's business grew until he employed over a hundred journeymen cabinet-makers. Nevertheless, he undoubtedly went through a severe struggle before he succeeded. In fact, he was never so successful that he could afford to be independent; he was obliged to follow the tastes of the times, which accounts for the deplorable deterioration of his style after 1820. His ideals of craftsmanship, however, never permitted him to turn out poor construction or slipshod workmanship, so that he never made cheap furniture. Consequently, his market was limited to the well-to-do class which was none too numerous in those post-Revolutionary days. During the first few years of his New York career, before his work was appreciated, he must have had a hard fight for business existence, but he held to his artistic ideals and perfected his style and workmanship. It was his very attitude of exclusiveness, no doubt, which at last caught the fancy of wealthy patrons. The Astors took him up between 1798 and 1800 and started the Duncan Phyfe vogue, and he was saved from bankruptcy. In

spite of Phyfe's just claim to artistic recognition, and in spite of

his prominence in the commercial life of New York, his name is

scarcely mentioned in any of the local histories or biographical

dictionaries. In fact, the only mention of any interest that I have

found has been taken from the official narrative of the Erie Canal

Celebration, prepared by Col. Wm. L. Stone in 1825. After Gov. DeWitt

Clinton had performed the ceremony of the commingling of the waters

of Lake Erie with those of the Atlantic, a portion of the water was

placed in an American-made glass bottle to be sent to France as a

gift to General Lafayette. The bottle was placed in a wooden box or

casket made from a cedar log brought down from Erie in the first

canal boat, Seneca

Chief,

and the man who constructed the casket was Duncan Phyfe, the most

skilled wood worker in the city.

In the course of his investigations Mr. Hagen discovered an old bill made out by Phyfe on January 4, 1816, for goods sold to Charles N. Bancker of Philadelphia. It is valuable for several reasons: it is a personal document a hundred years old, in the handwriting of a man of distinction, and it gives the current prices for the better class furniture of those days. Single chairs were priced at $22 each, a sofa at $122, a pier table at $265, a pair of card tables $130, etc. While our factories are to-day able to turn out well-made furniture at lower prices than these, it is not to be compared with the Phyfe pieces for beauty or for thoroughness of workmanship. For hand-made furniture it was not costly, for rents and wages were lower then, and these same pieces could not be duplicated to-day, with anything like the same grade of materials and workmanship, at those prices. The chairs would cost from $25 to $35 and the other pieces in proportion. In connection with these figures it is interesting to learn that the journeymen cabinet-makers of that day had an effective and dignified union organization which fixed the prices on all work. There are copies in existence of an interesting old book published in 1796 by "The Journeymen Cabinet and Chair Makers of New York," which gives in detail the union's prices for every sort of furniture then made, with all possible modifications, and states that the journeymen shall "work ten hours per day; employers to find candles." Phyfe designed his furniture by fashioning models in his workshop. He was a wretched draftsman, as is shown by two sketches on the back of the aforementioned bill, which offend all laws of proportion and perspective. He was an artist with his tools, not with his pencil. Phyfe's work may be divided into three periods: the Adam-Sheraton from 1795 to about 1818; the American Empire from 1818 to 1830; the "butcher furniture" from 1830 to 1847. On the work of the first period and part of the second his claim to immortality rests. As has already been stated, the deterioration of his style was through no choice of his but because he was obliged by commercial conditions to follow the fashions of the times. Even the quality of workmanship fell off during hard times because there was no market for expensive furniture and Phyfe had to make a living. As a result the beautiful carving and finely modeled tool work gradually disappeared and his furniture became less and less distinctive. After the War of 1812 times were especially hard; there was a financial panic in 1817; and probably Phyfe made very little of his finer furniture during these years. After 1818 he yielded gradually to the popular influence of the styles of the French Empire, and the first of his Empire pieces display considerable merit, but he was soon obliged to give way before the demand for heavier and more showy designs. In short, it is safe to say that the finest examples of Phyfe's work now in existence those worthy to be known as "Phyfe furniture" belong to the period prior to 1812. Before venturing into an analysis of Phyfe's peculiar style and a study of its sources and development, it may be well to mention briefly the various kinds of furniture on which he specialized. These were chiefly chairs, sofas, tables, and sideboards. He worked in mahogany, plain and veneered, importing the finest quality of Cuban and Santo Domingan wood. It is said that his insistence on quality in the raw material led the West Indian exporters to speak of the very finest timbers as "Duncan Phyfe logs," and to mark them with his initials. He is said to have paid as high as $1,000 apiece for some of these logs. He was very proud of his wood and owned a private yard where he stacked his lumber. Thus he made certain of perfect seasoning. He selected and cut his veneering with the utmost care and applied it with Peter Cooper's best glue. Except for a little satinwood and bird's-eye maple, Phyfe used practically nothing but mahogany, until he was forced to supply the demand for rosewood toward the end of his career. Of his sideboards, I have never seen one in the style of his early period, and I am led to believe that he made few if any until after 1820. He is said to have followed Sheraton, Hepplewhite, and Chippendale in his sideboard designs, but those I have seen have all shown Empire characteristics, and they range from very fine to commonplace. Two

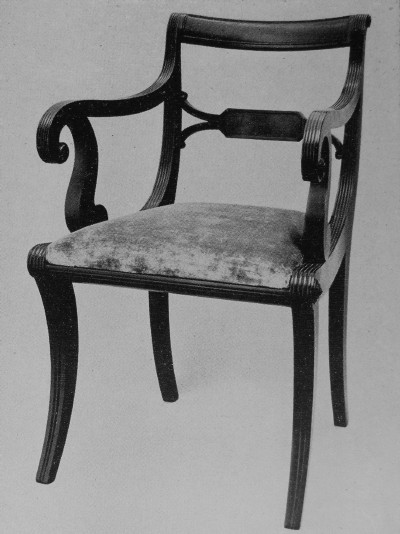

types of chairs are especially worthy of mention. In one

probably

the earlier the back shows two horizontal pieces, finely

carved

and modeled, and curved to fit the body. In the other the motif of

the back is the lyre, which indicates the approach of the Empire

feeling. This lyre, often finely carved and with strings of brass or

whalebone, was one of Phyfe's favorite details, not only for chairs,

but for tables, sofas, and other pieces.

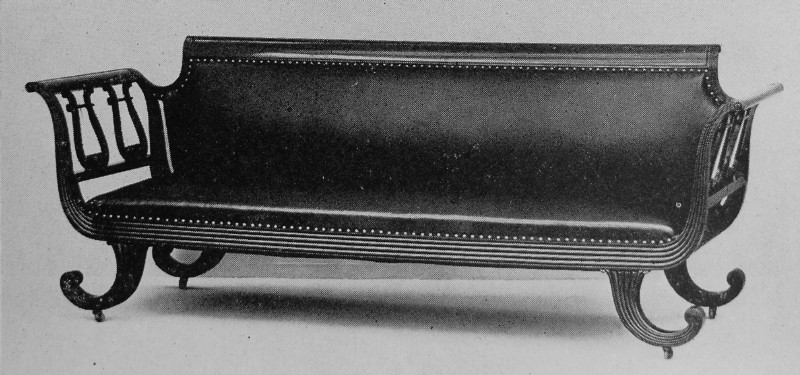

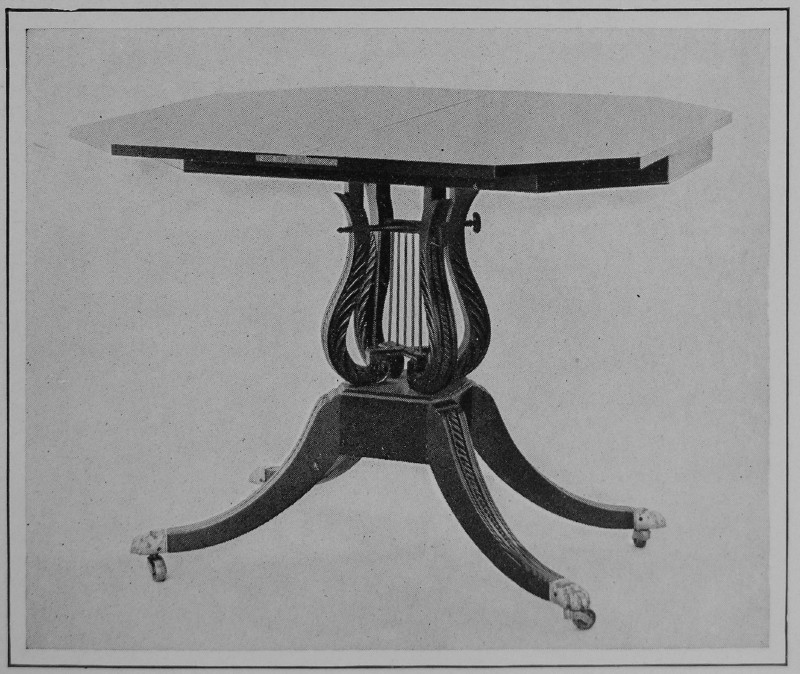

Phyfe's chairs are alone sufficient to give the lie to the claim that he was a mere adapter of Sheraton's designs, for while Sheraton loved straight lines and right angles, Phyfe was devoted to graceful and delicate curves. A few of his early chairs show straight legs, but for the most part his chair legs sweep outward in a concave curve of infinite grace. This is true not only of the later period, when it might have been explained on the ground of Empire influence, but of much of his earlier work. The chair backs, too, were curved gracefully backward, and the line of the stiles, seat, and front legs usually formed one continuous curve. His sofas and settees show many of the characteristics of the chairs, with the same mastery of sweeping curve, exquisite proportion, and dainty detail, and with the lyre motif used frequently at the ends. His tables are equally distinguished in design and workmanship. He made several types of dining tables, both extension and sectional, with the lyre frequently appearing in the pedestals. The same motif appears often on his smaller tables, but their more noticeable characteristic is the avoidance of straight lines in both tops and legs. The leaves are nearly always slightly rounded, with sometimes the clover-leaf pattern at the corners. The pedestals are often either crossed lyres or finely carved pillars, to which are attached three or four legs, curving gracefully outward in the characteristic con cave sweep. Phyfe certainly never copied this curve from his Georgian predecessors. He seldom if ever made a table with four vertical legs at the corners until after 1830. A specialty of his was a card table standing on a tripod fitted with an internal mechanism which made it possible to move two of the legs outward and drop a leaf, so that the table could be placed close against the wall. These tables, which cost about $60 apiece, cannot be duplicated to-day for less than $75. In the handling of mahogany to bring out its highest value of texture and color, Phyfe never had a superior. He loved the wood and was a master in the treatment of both carved and plain surfaces. He used no marquetry, no inlay of lighter woods, but frequently he placed most effectively an inlaid panel of crotch mahogany veneer on a surface of plainer wood. The result is at once elegant and restrained. His simple, plain moldings and reedings are clean-cut and fine. He was very fond of parallel rows of reeding along the legs of chairs and tables and the arms of chairs and sofas, which accentuate the curving lines and the effect of slenderness. His table drawers are often edged with a delicate, plain, rounded molding that is charming. His simpler carving was executed with the utmost care and precision; his more elaborate work was a marvel of the art. The acanthus was a favorite motif on sofa legs, table pedestals, etc., and wheat ears, swags, and other classic details often appear on the backs of chairs and sofas, in low but sharp relief. This carving was always refined and well placed. About 1805 Phyfe, like Sheraton, accepted the demand for brass mountings, but in spite of the on ward sweep of the Empire vogue he kept his brass-work delicate and refined. He made lyre strings and drawer pulls of brass, and used brass lion paws for table feet. Duncan Phyfe unquestionably exerted a restraining and corrective influence on American taste. Sir Purdon Clark, when director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, asserted that as a workman and designer Phyfe surpassed any of his British contemporaries. His best work was well-nigh perfect in line, proportion, and workmanship, and in its details and general design it displayed a character all its own. Moreover, he exhibited a remarkable knowledge of and feeling for the principles of classic art. When and where he acquired this understanding it would be difficult to say. He was only a boy when he reached this country, and he probably learned his trade in Albany. He could not have gained an extensive artistic education before he left Scotland. In general, Phyfe's style throughout seems to be composed of three elements, skilfully commingled the Adam-Sheraton, the Empire, and his own originality. His work undoubtedly was influenced by the Sheraton popularity and shows, probably unconsciously, some of the characteristics of the Scotch adaptation of Sheraton's style. Much more clearly marked, however, is Phyfe's kinship with his Scotch predecessors, Robert and James Adam. There are in existence Adam chairs which bear a close resemblance to Phyfe's. In the Victoria and Albert Museum, in England, there are two Adam chairs which are particularly interesting from this point of view. One has a lyre in its back, with brass strings, and the other shows the typical Phyfe sweep of curve along the stiles, seat, and front legs. Other authentic Adam chairs exhibit details more like those of Phyfe's early work than anything Sheraton did. It

is not unlikely that Phyfe owned books of both Adam and Sheraton

designs from which he gleaned ideas while developing his own

individual style. Gradually

he added what he saw fit from the Empire, always avoiding excess in

his new departures until the age of monstrosities had fully set in.

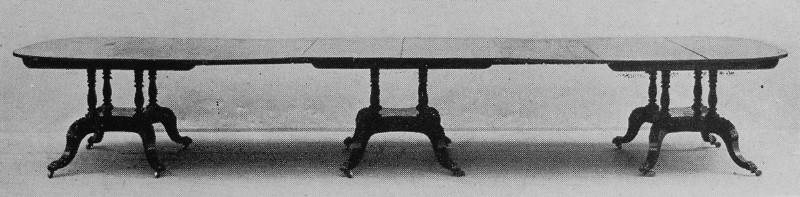

With a hundred men employed in Phyfe's shop it seems strange that so few pieces of his work have come down to us. But we know that his best furniture was made for a small and wealthy clientθle and it may be that most of his men were busy with some sort of inferior work not now connected with his name. Mr. Hagen spent years searching for authentic Phyfe furniture and it is not likely that he missed very much. Mr. R. T. Haines Halsey of New York has the largest, and in every way the finest, collection I have seen some twenty chairs and fifteen other pieces. Mr. Dwight Blaney of Boston and other New York and New England collectors have acquired a few excellent pieces. The pieces on view in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, unfortunately do not represent Phyfe's best work. The most notable piece is a sectional mahogany dining table, of unusual design, eleven feet six inches long by four feet ten inches wide. It is in excellent condition and was the bequest of Mrs. Maria P. James of Norwalk, Connecticut. It is in three sections, each standing on a four-legged base carved in acanthus patterns and with brass lion's-paw feet. Accompanying this table there is a set of five lyre-back chairs. The museum also owns a smaller table of similar design, and an Empire cabinet has been loaned to the collection by Miss Anna P. Livingston. It is of fine mahogany veneer with glass doors and stands about six feet tall. If it is an authentic Phyfe piece, it represents his later Empire style. Present-day values of Phyfe furniture depend entirely on how badly the collector wants them. Mr. Halsey has paid widely varying prices for his, his chairs averaging $100 apiece and his tables $200, but his are especially fine pieces. A fair value would be $75 for side chairs, $85 for arm chairs, and $100 for card tables, with the values of sofas and dining tables running up as high as $500. But as there is little likelihood of there being any extensive traffic in genuine Phyfe furniture, these figures have but little significance. Phyfe furniture is rarer and finer, to my mind than Chippendale's. I don't know that any one has ever attempted to counterfeit Phyfe furniture. Perhaps the fakers have not realized its value. It was seldom marked with Phyfe's name, and other American Empire work has been palmed off occasionally as that of Duncan Phyfe. The collector's safeguard is an intimate knowledge of Phyfe's handiwork; no other American made anything comparable to it. A

reproduction is not an antique, and true collectors scorn

reproductions; but authentic Phyfe pieces are so rare and his style

so worthy of preservation that this sentiment should not be allowed

to stand in the way of its perpetuation through the medium of fine

reproductions. Only in this way can the work of our greatest American

cabinet-maker be brought into modern American homes. Here is a great

opportunity for American furniture manufacturers, provided they have

the vision and skill to re produce Phyfe's work and not murder the

style by inferior execution.

|