| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2008 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

II BEECHNUT Margaret felt very much disappointed to

have Carlo go

away. After a short time, however, she began to think of other things,

and

forgot her trouble altogether. The sun shone so cheerfully, and the

fresh,

spring-like air produced so invigorating an effect as to make her feel

quite

bright and happy. "I think I'll take a little walk," said

she. So she got up and walked along the piazza. Between the piazza and

the

garden there was a little yard, and the snow had entirely melted away

from the

part of the yard next to the house. The ground was bare, and she

stepped down

on it. A plank walk led along by the side of the yard, and as she was

not quite

sure it was right for her to go on the ground, she went to the plank

walk and

passed along on it between some rose and lilac bushes on one side and a

shed on

the other. At length she came to a door leading into

the shed.

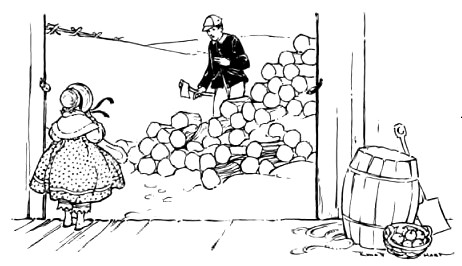

It was shut, but she opened it and looked in. On the opposite side of

the shed

was a large double door which was wide open, and she heard the sound of

some

one cutting wood out in the yard beyond. "I wonder who that is," said she. She walked through the shed expecting that

when she

reached the double door she could see who was cutting wood, but she

found that

the woodpile was in the way. She thought the chopper must be a boy who

worked

for her aunt, and who commonly went by the name of Beechnut. As she

wished very

much to go where he was she began to call as loudly as she could,

"Beechnut! Beechnut!" The sound of the ax ceased, and Beechnut

came around

the end of the woodpile. He was a tall boy about fourteen years of age.

His

real name was not Beechnut, but Antoine Bianchinetti. He had been

brought up in

Paris until two years ago, when his father came across the Atlantic

with him to

Canada. Shortly afterwards, his father decided to

remove to

the United States. He took with him all the money he had, and a supply

of

provisions to eat by the way, and he and Antoine started to travel

through the

woods on foot. In the midst of the journey Antoine's father fell sick

and died,

and Antoine had to come the remainder of the way alone. Soon he ate all

his

provisions and then began to live on what the farmers would give him as

he went

along, and, to some extent, on the nuts he found in the woods. In this manner he continued for two or

three days and

then reached Franconia. The house of Mrs. Henley was near the road, and

when he

came to it he sat down near the front gate on a mounting-stone — that

is, a

stone with a step by the side of it, which was used for mounting horses

and

getting into carriages. He sat there waiting for some one to see him

from the

house and come and offer him something to eat. This was what he always did when he was

hungry. He

was too proud to beg. At all the farmhouses where he stopped he never

would go

to the door and ask for food, but would sit down on a log or a stone

near the

house until the people saw him. Then, if they were kind-hearted, they

would

come out and ask him where he was going, and if anything was the

matter. If

they were not kind-hearted he did not wish for their help. He would

rather go

on alone and live on nuts. He had plenty of money with him, but it

was all in valuable

gold pieces, and he did not think that the farmers would be willing to

change

them. Besides, he was not sure it would be safe to have it known that

he had so

much money in his possession. When Antoine reached Mrs. Henley's house

he sat down

and waited patiently. At last Frank saw him and went and told his

mother there

was a boy out on the mounting-stone with a pack on his back and a cane

in his

hand, as if he were a traveler. Mrs. Henley told Frank he might go out

and

speak with the boy and ask him if he had been traveling far, and what

his name

was, and if he were hungry. So Frank went out to the stranger and

said, "My

mother wants to know if you have been traveling far." Antoine hesitated as if making a

calculation. He was

running over in his mind the distance from Paris across the ocean to

Montreal,

and from Montreal to Franconia. "About four thousand miles as near as I

can tell," he said. "What is your name?" asked Frank. "Antoine Bianchinetti," the boy replied. Frank studied on this singular name a

moment in

silence. He could make nothing of the first part of it, and he thought

the

second word was meant for Beechnut. "Where are you going?" Frank inquired

after

a little pause. "I don't know," responded Antoine, shaking

his head mournfully. "Are you hungry?" asked Frank. "Yes," said Antoine, "I am hungry and

tired." Frank then went in and told his mother that the boy out there said that he had walked four thousand miles, and that his name was Beechnut.  Mrs. Henley laughed at the absurdity of

this, but

Frank persisted that it was what the boy had told him. He might be

wrong, he

said, about the distance the boy had walked. "But I am very sure,"

declared Frank with great earnestness, " that the boy said his name was

Beechnut, only he did not pronounce it very well." Mrs. Henley sent out to invite the

stranger to come in. She gave him

some supper, and then becoming more and more interested in him and in

his

story, she invited him to stay all night. Her husband was away from home. He had

business which

made it necessary for him to travel a good deal, and the directing of

the

household affairs, and those of the farm also, fell largely to his

wife. It

happened that he returned the day after Beechnut, as Frank called him,

arrived,

and when he and Mrs. Henley had consulted together they decided to

engage the

boy to remain and work about the house for wages. Antoine hid the money he had brought with

him in the

barn, and said nothing about it for some time. However, as soon as he

became

well enough acquainted with Mr. Henley to feel certain that he was

trustworthy,

he took it to him and gave it into his care. Mr. Henley was much

surprised, but

he received the money and put it out at interest for Antoine's future

benefit. The name Frank had given the stranger was

adopted by

the other members of the family; but in the village he was generally

called

Antonio or Antony, and some of the village boys shortened this to Tony.

As he

was very good-natured he did not care what they called him. He had now

been at

Mrs. Henley's house two years and was a great favorite with all who

knew him. It has already been related how Margaret

called to

him when he was chopping in the yard. He came around the woodpile, and

she

said, "I want to go where you are." "All right," Beechnut responded, "and

would you like to ride or walk?" "Why — ride," said Margaret. "And will you ride in a sleigh, a

carriage, a

cart, or on a drag?" asked Beechnut. He was always doing or saying something

which the

children considered funny. Margaret smiled, and after hesitating a

moment

concluded to say, "On a drag." "And how will you be drawn," said

Beechnut,

"by oxen, or a horse, or a locomotive, or a bear?" "By a bear," was Margaret's answer. "Very well," said Beechnut, and he went

around the end of the woodpile and disappeared. Margaret waited some minutes, and she was

beginning

to wonder what had become of him when she heard a noise behind her. She

turned,

and there was Beechnut all covered up with a bearskin carriage robe,

and he was

crawling along on his hands and knees, growling as he came. "Why, Beechnut!" exclaimed Margaret. Beechnut threw off the bearskin and rose to his feet. He then went to the side of the shed and got a large tray such as is used in carrying dishes to and from the table. It was much worn and had been thrown out from the house. Beechnut put it down on the snow and told Margaret it was her drag. He helped her to seat herself on it, and it was so large there was plenty of room.  Next he went and got a strap and fastened

it to the

handle of the tray. After that he wrapped himself again in the

bearskin, got

down on all fours, took hold of the end of the strap, and dragged

Margaret

along over the snow, growling all the time like a bear. The side of the woodpile which was toward

Margaret

was covered with snow, but Beechnut took her around to the other side

where the

sun shone warm and the snow had melted off. He drew her over the chips

to a

pleasant corner and placed her so that she could lean against a smooth

log.

Then he laid the bearskin on the woodpile and returned to his work. But

he had

not been chopping long when Margaret said, "Beechnut, I wish you would

make me a seat with the bearskin." So Beechnut put a short board down near

the end of

the log which was at Margaret's back, and supported it on two sticks to

make a

little bunch. He then spread the bearskin over the seat and log in such

a

manner as to form a sort of cushioned chair that was both soft and

warm. When

the seat was finished Margaret sat down on it and Beechnut once more

resumed,

his work. He cut off several logs and split them with a beetle and

wedges,

talking all the time to Margaret and making her laugh. After a while, Margaret got up and said it

was time

for her to go in. Beechnut told her he was very much obliged to her for

giving

him her company, and that the next time she came out to see him he

would make

her something. "What will you make me?" asked Margaret. "Oh, I don't know exactly," replied

Beechnut. "I will make you a horse or a seesaw, whichever you

prefer." Beechnut then took Margaret up in his arms

and

carried her across the snow back to the shed. He put her down at the

door, and

she walked through the shed to the other yard and thence along the

planks to

the piazza and went into the house. |