|

1999-2003 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click Here to return to |

|

1999-2003 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click Here to return to |

VI

THE MARLIN OR SPEARFISH

“WITH HIS MOUTH WIDE OPEN AND HIS FINS ALL SPREAD, WALKING ON HIS TAIL AND STANDING ON HIS HEAD SPEARFISH OR SWORDFISH, CALL HIM WHAT YOU WILL, HE’S THE VERY KING OF THE FIGHTING DEVILS STILL.”

THE MARLIN OR SPEARFISH

(Tetrapturis mitsukurii)

I JOURNEYED from Maine to Santa Catalina Island, California, at the end of August to attempt to take a marlin. This fish is the jumping-jack of the Pacific ocean, and I had heard so much of his acrobatic performances that I decided that no journey would be too long if I could but capture one.

The marlin is sometimes called the Japanese swordfish, which is a misnomer, for his so-called sword is a spear shaped like a marlin-spike, hence the name, marlin. He is a true spearfish and is to be found in the warm waters of the Pacific ocean.

He appears, as a rule, off the island of San Clemente in early September, coming from the south. San Clemente is twenty miles due south of Santa Catalina Island.

Some years these fish have been very numerous off the latter island during the second half of the month of September, but I was disappointed when told on my arrival at the Tuna Club that but one fish had so far been taken during the summer. Others had been reported but they were few and far between.

As the members of the club were all fishing for swordfish (Xiphias gladius) I had to follow suit, for no tuna were reported.

We roamed the ocean and “Shorty,” my boatman, and Pard, his dog, looked for swordfish. I kept a line wet most of the time, hoping for a stray marlin.

After ten days’ swordfishing I heard that the marlin were reported as being plentiful off the island of San Clemente and decided, Mohammed-like, to go to the mountain.

What makes the waters around the Channel Islands ideal for fishing is the fact that on nine out of ten mornings during the summer months you will find the ocean as smooth as glass. About noon the westerly trades begin to blow. Sometimes it is a gentle wind but often it blows hard and the sea becomes too rough for comfortable fishing after two o’clock.

We made an early start from Avalon in order to take advantage of a smooth sea, coasted along lovely Santa Catalina, cleared the island, and steered due south for the camp at San Clemente.

It was not long before the fog which overhangs the islands in the early mornings lifted so that we could see San Clemente in the distance.

THE CAMP AT SAN CLEMENTE

San Clemente is evidently the overflow of a great volcano and is a mountain of rock and lava rising from the sea. It is studded with caverns and caves, not only along the coast line but beneath it and up its cañon-riven sides.

The flora consists of arborvitae, ironwood, cactus, and ice-plants, and wild oats grow on the tableland.

The island belongs to the United States government and is leased as a sheep-ranch. It supports some fifteen thousand sheep and wild goats which feast upon the wild oats and use the caves for shelters. The only inhabitants are the sheep herders and Pete Schneider, a Belgian, who runs the camp at Mosquito Harbour where we were bound.

We reached the island about four hours after leaving Avalon, having seen but little sea-life on the way—only a few sunfish jumping here and there and a school or two of porpoises.

We found the camp a very simple one but clean and the food very good. We slept under canvas, washed and shaved out of doors, and took our meals in a wooden shack.

The island is about eighteen miles long and has great majestic beauty of outline. The waters that surround it have been celebrated for fishing. Tuna, yellowtail, white sea-bass, black sea-bass, and marlin are to be found in plenty at the right seasons.

We found but one party fishing there and they arrived home at suppertime empty handed.

I told “Shorty” to find out from their boatman where the marlin were trading, for several fish had been taken during the week. The jealous boatman gave “Shorty” the wrong advice by telling him the fish were to be found in shore.

We started the following morning bright and early and zigzagged the whole length of the island but found only one fish lazily sunning himself on the surface. Try as we would we could not persuade him to look at any bait.

We trolled for ten weary hours. I say weary hours for it is a strain to troll a flying-fish bait weighing a pound at the end of one hundred or more feet of line held by thumb pressure only, for one must be ready to give line if one has a strike as the fish pick up the bait and move off before gorging it. That is the theory but not my experience, for the following day I trolled with only seventy-five feet of line and struck the fish when he struck me.

That night a kind sportsman told me that we had been on the wrong track, that the fish were off shore at the eastern end of the island. It seems the kelp-cutter from the potash factory at San Diego had been cutting the kelp, some of which had floated off shore and harboured much bait, and the marlin were feeding on this small fry.

We were off at seven the following morning and rounded Eastern Point where the sea was breaking on the reef in great circles of white foam.

We trolled around the point, into and around Smugglers’ Cove, a celebrated fishing ground, and then made a bee line off shore. About six miles out we found acres of floating kelp with myriads of small fish jumping about, evidently being pursued.

It was not long before we lost the teaser. A teaser is a flying-fish attached by twenty-five feet of line to a fifteen-foot bamboo pole. No hook is used. This flying-fish skitters along on top of the water and acts as chum. My bait was fifty feet further astern.

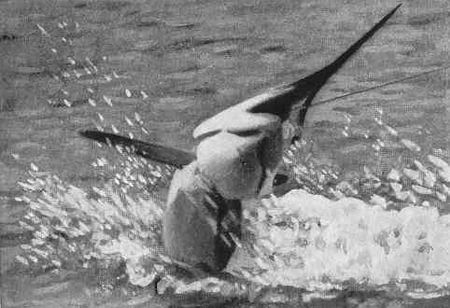

MARLIN WHEN FIRST HOOKED

THE END OF A JUMP

I soon had a strike and hooked a marlin. He jumped half out of water and tried to shake the hook loose but I had driven it well home. He then performed a stunt that was beyond all my fishing experience. We were following the fish at full speed at the time and the reel brake was on, but this strong and lively fish jumped twenty-two times in a straight line tearing the line off the bending rod as he went. He then sounded and jumped again, fought on top of the water, swam in circles, and performed every kind of piscatorial acrobatics known. He jumped twenty-nine times and in forty-five minutes I had him alongside stone dead. My first marlin! I was warm with excitement and pleasure, for my journey of thirty-five hundred miles had now been well worth while. “Shorty” shook me by the hand and suggested that we land a few more, which we proceeded to do after stowing our fish on board.

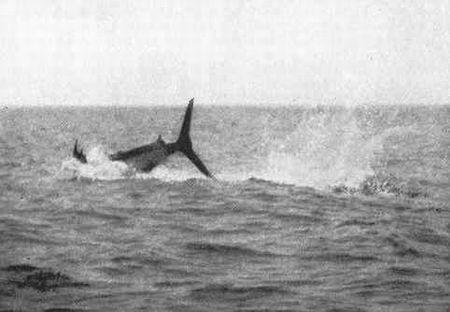

I soon had another strike and hooked the fish. This one proved to be a perfect dancing-master, for after showing his beak and shaking his head he made a run of about one hundred feet, then rose up out of the sea and did a song and dance on the end of his tail for fully one hundred yards. We were following him at full speed but he was simply stripping the line from off the reel. Then he disappeared below the surface and “Shorty” said: “You have lost him.” The line was slack and I was reeling in as fast as I could when suddenly I saw the spearfish on top of the water, charging down upon us, while following him was the bag of the slack line cutting the spindrift off the tops of the white-crested waves. He was coming at great speed. I yelled: “Port your helm, ‘Shorty,’” and as the boat turned the fish shot by on the surface close under the stern.

Would he have gone through or under the boat had we not altered our course? I wonder.

As the line became taut the fish jumped clear of the surface. He jumped in all twenty-two times and in thirty-five minutes came alongside belly up, when it was found that he was hooked in the tail.

The fish was beautiful to look at. The greater part of his body was bright silver and he was striped with translucent royal purple stripes an inch wide. His back was dark green bronze and his tail and fins were mauve.

When in the water he is a blaze of glory but the colours soon fade after the dead fish is exposed to the air. A mounted marlin gives one an idea of the graceful shape of the fish but no idea of his real beauty of colour.

It took us some time to hoist the dead fish on board, for although a fish only weighs in the water the number of pounds that the water he displaces would weigh, any part of the fish that is above the surface is of course dead weight.

The first fish had been laid across the stern of the boat; that was easy, but this fish had to be roped on to the narrow deck on the port side.

His weight at the moment was over two hundred pounds and the combined weight of fisherman and boatman was only two hundred and sixty pounds. “Shorty” fastened the peak halliard block to the bill of the marlin while I roped his tail. Then the fish was hoisted half out of the water but I did not have strength enough to lift the other half on board. I told “Shorty” to gaff the fish in or near the anal fin and give me a hand, get the fish on board, and lower away.

ONE HUNDRED YARDS ON END OF TAIL

Now a funny thing happened. It was rough and we were rolling about in the trough of the sea. As “Shorty” attempted to drive the gaff home the end of the bamboo teaser pole, which had been carelessly thrown on top of the deck house and was foul of the mast, caught “Shorty” in the back as the boat rolled and catapulted him into the sea. He climbed back on board a very wet and surprised sailorman for he did not know what had hit him.

We soon found the floating kelp and the jumping small fry and had not been trolling more than a quarter of an hour before we ran into a school of marlin. Four or five rushed after the teaser and pulled the pole overboard. It went bobbing away astern, first disappearing entirely, then shooting straight up on end. This happened several times in a most comical manner before the fish disconnected the flying-fish from the line to which it was made fast.

A moment later a marlin took my bait, I hooked him, and the music began again. The fish emerged with beak open and shook himself, then rushed on top of the water for one hundred yards and jumped clear of the surface. He then pirouetted once or twice on the end of his tail and jumped again. After jumping sixteen times in twenty minutes he sounded and fought more like a true swordfish than a marlin. He was a tough customer to handle and it took me eighty minutes to land him.

I looked at my watch as he was gaffed and found it was just three hours and a half from the time of the strike of the first fish!

“Shorty” remarked: “Some fishing, eh? Let’s corral another.”

I insisted on having lunch first, which we devoured while the launch with her six hundred pounds of fish on deck tried hard to roll over.

A heavy sea was running. It had been all I could do while playing the last fish to keep from going overboard. Had it not been for my patent rod rest which held my rod steady and gave me something to hold on to, I should have been in the sea and like “Shorty” arrayed in an Isadora Duncan bathing suit.

It was too rough to fish so we started back to camp. We had not gone far before “Shorty” saw a swordfish, a true broadbill. He slowed the launch down and wanted me to try him. I told him to give the fish a wide berth and go full steam ahead. I wanted no five-hour fight with a broadbill in that rough sea after the three hours and a half of calisthenics that I had been through. In fact I had had enough fishing for one day. How seldom that happens!

On our way back to the camp we ran into a large school of marlin. The crest of every big wave was pierced by their large dorsal fins as they rode on the top of the heavy swells. I never saw such a fish picture before and it was heartrending to think that it was too rough to fish with safety. We had a teaser pole out, which was torn loose. The fish seemed ready to devour everything in sight.

It was too rough to go back to Avalon that night so we remained at the camp.

The wind was strong from the northwest and as our course was due north we had a rough trip of over five hours and a half the following day and arrived at Avalon with everything on board afloat.

The fish were weighed on the Tuna Club scales thirty hours after they had been taken and tipped the beam at 189, 186, and 183 pounds. These fish seem all to be of about the same length, from ten to eleven feet, their weight depending on their girth.

Marlin are the most sensational fish that swim. Their pace and agility, the way they walk the tight rope on the end of their tails, and their power to jump have to be seen to be believed.

I am told that the heavy fish—record 372 pounds—do not jump much and are hard to kill.

A friend of mine saw a marlin in the fish market at Honolulu that weighed 725 pounds, and it is said that fish exist that weigh one thousand pounds or more.

THREE AND ONE HALF HOURS’ FISHING AT SAN CLEMENTE

The tackle allowed by the rules of the Tuna Club is a rod of wood consisting of a butt and tip not to be shorter than six feet nine inches over all; the tip not less than five feet in length and to weigh not more than sixteen ounces; line not to exceed standard 24 thread. The hooks used are the regulation tarpon trolling-hooks. The wire leader is twelve feet long and the bait a flying-fish. I fished with 1,000 feet of line but most fishermen carry from 1,200 to 1,500 feet.

RECORD

The first marlin, weighing 125 pounds, was

taken in 1903.

There was another taken in 1905 and again in 1908.

9 were taken in 1909

9 were taken in 1910

34 were taken in 1911

100 were taken in 1912

22 were taken in 1913

24 were taken in 1914

47 were taken in 1915

70 were taken in 1916

315 fish

The largest fish weighed 340 pounds.

Click

here to continue to the next chapter of

Some Fish and Some Fishing