1999-2002

(Return to Web Text-ures)

Tales Told in Twilight

Content Page

Click Here to return to

the previous section

(HOME)

1999-2002 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click Here to return to Tales Told in Twilight Content Page Click Here to return to the previous section |

(HOME) |

ROBIN HOOD AND HIS MERRY MEN.

ROBIN HOOD AND HIS MERRY MEN. Robin Hood, as we know, dwelt in the Yorkshire Forest of Barnsdale, though in Sherwood Forest he seems to have been at home. One day, this most proud and courteous of outlaws declared that he could not dine till he got some guest who should pay for their cheer. So his faithful followers, Little John, so called in sport be.cause he was seven feet high; Will Scatheloek, whom men named also Scarlett, and Much, the miller's sturdy son, he sent out toward Wafting Street, that they might perchance make prize of some rich traveler. Then, before long, they fell in with a knight riding through one of the forest glades, yet in little knightly pride, for he sat downcast on his sorry steed, thinly clad, all woe-begone and poverty.stricken of aspect, aud wept as he went along. "A sorrier man than he was one Rode never in summer's day!" All the same, Little John knelt courteously to give him his master's pressing invitation, which the knight was nothing loath to accept, saying he had heard much good of Robin Hood. So they all went together to Robin's lodge among the woods, where the hungry outlaw also welcomed his guest with a great show of friendliness, and when they had "washed and wiped together," they sat down to dinner. A good meal it was, bread and wine in plenty, with venison, swans, pheasants, and every kind of game; and the starveling knight confessed that he had not had such a dinner for three weeks. "If I come again, Robin,

Here by this country, As good a dinner I shall thee make As thou hast made to me." Robin thanked him, but said that he must now pay before he went, since it was not seemly that a yeoman should be at the cost of entertaining a knight. Alas! replied the knight, he had no more in the world than ten shillings, which he was ashamed to offer. In that case, declared Robin, he would not take a penny, but wou]d rather lend his guest money, if in need. To make sure, however, he bid Little John examine tlie knight's mantle, which in those days was a rider's baggage, and, this being spread on the ground, his "coffer" was found to contain no more than half a pound, as he had said. Robin Hood asked how one of his degree came to be so poor, and heard in reply a moving tale of family misfortune. The knight's son had had the misfortune to kill a knight of Lancashire, and to get him out of this trouble, the father had been forced to pledge his lands to the rich Abbot of St. Mary. Now the day was at hand on which he must pay up four hundred pounds, or see his inheritance pass into possession of the greedy monks. His friends had all abandoned him in his poverty; they pretended not to know a man at the point of ruin; nobody would lend him money or go bail for him. So he saw nothing for it but to go over the salt sea to Palestine. "And see where Christ was quick and dead,

On the Mount of Calvary. Farewell, friend, and have good day-- It may no better be!" But it was not Robin Hood's way to turn his back on one in distress. Even his men wept for pity of the poor knight; and now, ordering the best wine to be brought out for a guest who could pay only with thanks, their master sent Little John to his treasury for four hundred pounds, which he counted out as a loan, to be repaid that day twelvemonth, under the same greenwood tree, on no other security than the love of Our Lady. Moreover, Robin and his friendly men gave the knight scarlet and green cloth to make a good suit of clothes, and a good horse and a new saddle, and a pair of boots and gilt spurs; and Little John was lent him to go along as squire, since it seemed unbecoming for a knight to ride without a single attendant. This knight, then, Sir Richard of the Lee by name, turned from his sad way to the Crusades, and went joyfully back, blessing the outlaws, as well he might, for "the best company that ever he came in." Without fail, Our Lady helping him, he promised to keep his tryst that day twelvemonth under the greenwood tree. Next day, there was joy and revel at St. Mary's Abbey, where the proud priests thought that their debtor could not discharge the bond, and that they would forthwith enter into his goodly heritage, worth by the year as much as had been lent upon it. The prior, indeed, had pity on the poor man, whom he believed to be already suffering hunger and cold far beyond the sea; but the abbot, and that "fat-headed monk" the cellarer, were bent on exacting their bond; and here they had no less an officer than the high justice at hand, with other men of law, to adjudge the forfeiture if Sir Richard failed to pay, as like was. But as this good company sat at meat, to the gate came their debtor, he and his followers all in poor apparel, for he meant to fool the covetous monks before paying them their due. He came lowly into the hall and knelt down, pretending he had not a penny, and praying for delay. With haughty looks and scornful words, the abbot spurned his entreaties, not even having the courtesy to bid him rise. But his countenance changed, when Sir Richard leaped up, and out of a bag shook four hundred pounds of bright gold. '' Sir Abbot, and ye men of law,

Now have I held my day; Now shall I have my land again, For ought that you can say!" Leaving them to stomach their discomfiture as best they could, he strode out of these inhospitable doors, and now first arrayed himself in the good clothes he had got from Robin Hood. Thus, in gallant guise, he rode home to tell his wife and children what had befallen, and bid them pray for the kind outlaw. A year he lived at home, till he had gathered together four hundred pounds. This money in his cloak.bags, and carrying also a present of a hundred bows and a hundred sheaves of peacock-feathered arrows, inlaid with silver, in token of his gratitude for the loan, he set out to pay Robin on the appointed day, attended now by a goodly retinue of a hundred men, well armed and harnessed, so much had his state bettered through the year's delay. But as he rode along singing for lightness of heart, he came to a place where a wrestling was going on, and turned aside to see the sport. And from sport the wrestlers, it would seem, came to earnest, for the rest set upon a good yeoman, stranger as he was, who had deserved the prize, and came near to have killed him in this quarrel. Then our knight, "for love of Robin Hood," would not suffer that any yeoman should be wronged, so he and his men spurred into the fray, and laid about them, till the yeoman was allowed to take his prize--a white bull, a tall steed richly equipped, a pair of gloves, a gold ring, and a pipe of wine. For the wine Sir Richard paid him down five marks, and set it abroach on the spot, to restore good humor among all who were there. This business delayed him some three hours; and thus went by the hour of noon, when he should have been at his tryst with Robin Hood. Meanwhile Robin Hood awaited him impatiently, for he would not dine till the knight came to keep his word. Little John had returned to the greenwood, after playing some fine tricks of his own upon the sheriff of Nottingham. He, with Scarlett and Much, went out to see if any one were coming through the forest; and soon they were aware of a fat monk riding along the road, with some fifty attendants and more to grace his lordly state. When the outlaws stopped him, and gave their master's invitation to dinner, the monk called out on Robin Hood for a strong thief of whom he had heard no good. But all his men took to flight as soon as they heard the arrows whistling about their ears; and, willy-nilly, he was brought to the lodge in the greenwood. Now Robin could sit down to his dinner, and the monk had sullenly to let himself be entertained by this jesting crew. After dinner they asked who he was, and their unwilling guest confessed himself the high cellarer of St. Mary's Abbey; whereupon the chief called to mind how, half in jest and half in earnest, Our Lady had been appointed the borrow, or security, between him and that faithless knight: "'But I have great marvel,' said Robin,

'Of all this long day; I dread Our Lady be wroth with me, She sent me not my pay.' "'Have no doubt, master,' said Little John 'Ye have no need, I say. This monk it hath brought, I dare well swear, For he is of her abbey.' "'And she was a borrow,' said Robin, 'Between a knight and me, Of a little money that I him lent Under the greenwood tree .... "'Thou toldest with thine own tongue, Thou mayest not say nay, How thou art her servant, And servest her every day. " 'And thou art made her messenger My money for to pay.'" In short, the monk must tell how much money he had with him. Only twenty marks, he vowed; and if so, said Robin, he would rather lend to him than take a penny. But when they came to search, more than eight hundred pounds were counted out of this fat churchman's coffers, which Robin Hood took for himself, saying that, Our Lady was the truest woman he ever knew, who paid twice the sum for which she had gone bail. The angry monk cried out in vain. He was allowed to go on his way, declaring very truly that he might have dined cheaper in the next town. " 'Greet well your abbot,' said Robin, And your prior, I you pray, And bid him send me such a monk To dinner every day.'" Scarcely was the monk gone when up came the knight, giving for his delay a good excuse, as Robin judged, and said that whoever helped a worthy yeoman should always be his friend. Then Sir Richard would have paid down the four hundred pounds; but Robin told him that Our Lady herself had already paid the debt by her cellarer, so how could he take the money twice over? And to show how nobly he dealt with honest debtors, he made the knight a present of half the monk's money in return for that gift of bows and arrows we know of. " 'Have here four hundred pounds,

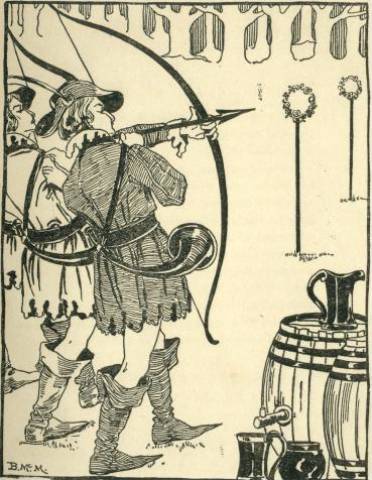

Thou gentle knight and true, And buy horse and harness good, And gild thy spurs all new. " 'And if thou fail any spending, Come to Robin Hood, And by my troth thou shalt none fail The while I have any good.'" So once more Sir Richard and Robin parted good friends; and all were merry but the poor monk, riding home to his abbey to tell what had become of its rents. After this Robin Hood and his men lived quietly in the greenwood for a time, till they heard news of a great archery contest at Nottingham. And though it was the proud sheriff of that place, Robin Hood's sworn enemy, who was thus inviting all archers of the north to try their skill, our outlaws were not the men to stay away from such a meeting. So to Nottingham they went, sevenscore strong; and we may be sure that their leader proved himself the best man at the butts. But when he had taken his prize there rose a cry that this was Robin Hood, and the sheriff's men tried to seize him. Then his men bent their good bows, no longer in sport, and fighting they made their way out of the town. But Little John was sore hurt by an arrow in the knee, so that he prayed his master to kill him outright, that he might neither hinder their escape nor fall alive into the hands of the sheriff. This Robin swore he would not do for all the gold in England, and, turning about from time to time to hold the pursuers at bay, they bore the wounded man to Sir Richard's castle, which, luckily, lay on their road. Right glad was the grateful knight to see his benefactor, and willingly he gave him refuge, shutting the castle gates, letting down the drawbridge and defying all the threats of the sheriff, who in vain summoned him to give up the king's enemy. The baffled sheriff then rode straight to "London town, all for to tell our king." This was not the first complaint against Robin Hood that had come to the king's ears. He sent the sheriff back, promising himself to be at Nottingham within a fortnight to deal with that bold rebel and his friend the knight--a thing much easier said than done. Meanwhile, after feasting with Sir Richard twelve days, and letting Little John be healed of his wound, Robin had gone back to the greenwood. Then that proud sheriff, not able to take the outlaw in his forest retreat, laid wait night and day for Sir Richard, till at last he caught him out hawking, and carried him off to prison at Nottingham, bound hand and foot. Straight way his wife got to horse, and rode to Robin Hood with her complaint: " 'Let thou never my wedded lord

Shamefully slain to be; He is fast bound to Nottingham ward, All for the love of thee?' Nor was Robin one to desert his friend in such a strait. With all his men he hastened to Nottingham, met the sheriff and his prisoner in the street, cut Sir Richard's bonds, drove away the guard; and as to the sheriff, fetched him down from his horse with an arrow, then smote off his head, and left him lying there--no more to trouble honest archers. Now was there more need than ever for both Robin Hood and Sir Richard to hide themselves in the woods. The king traveled to Nottingham with a great array, but could not come at the outlaws, though every day he heard how they were masterfully killing his deer. All he could do was to proclaim the knight a traitor and seize his lands, which yet he durst hardly bestow upon any other, since the new lord would never have peace so long as Robin Hood lived. Full of wrath as the king was, not less grew his curiosity to see this bold outlaw, who thus set him and his officers at defiance. To this end he took advice to disguise himself as a monk, a kind of bait sure to tempt Robin. Dressed like a portly abbot, with five of his knights also robed in monkly weeds, be rode into the forest; and sure enough he had not gone a mile there before up started Robin and his men. Robin took the king's horse by the bridle, saying: " 'Sir Abbot, by your leave, Awhile ye must abide. " 'We be yeomen of this forest Under the greenwood tree; We live by our king's deer, Other shift have not we. " 'And ye have churches and rents both, And gold full great plenty: Give us some of your spending For Saint Charity.'" In answer to this sturdy begging, the king said he had no more than forty pounds, which Robin forthwith divided, gave half of it to his men, and courteously returned the other half. Then the pretended abbot delivered him a message, as from the king, bidding him come to Nottingham, and showing him the royal broad seal as token, at the sight of which Robin fell reverently on his knees, declaring how he loved no man in the world like his king. So much had men belied him in calling him a rebel, when it was only sheriffs, keepers, bafiiffs, and other ministers of justice that he could nowise abide! In honor of the message he brought Robin Hood now bid the "abbot" stay to dinner, and served him with the best of their woodland cheer. The guest was amazed to see how many merry men came flocking up at the sound of their chief's horn, and how dutifully they did obeisance to this outlaw. "His men are more at his bidding Than my men be at mine!" So thought the king under his cowl. Then, after dinner, though the outlaws had drunk to the king's health, he was startled to see them handling their bows, half believing some treason was meant. But it was only to give proof of their skill in archery. Two wands were set up, fifty paces, too far apart judged the king, not knowing what sturdy arms these men had; and on each wand a rose garland, at which they were to shoot. Whoever missed the garland must lose his arrow and let himself be punished by a buffet on his bare head, for such was their custom; and even their chief himself had to submit to this forfeit of ill fortune. Twice Robin cleft the wand, but at his third shot, as will happen to the best of archers, he missed the garland by three fingers' breadth and more, whereupon his followers laughingly demanded that he should stand forth and "take his pay." Since so it had to be, he delivered himself to the abbot, desiring him to administer the buffet. He objected that this was not the part of a churchman; but when Robin urged him, giving him full leave to "smite on boldly," the king folded up his sleeve, and, without more ado, dealt the outlaw such a blow as had almost brought him to the ground. It was Robin's turn to be astonished. Then, looking hard at that stalwart monk who had such kingly pith in his arm, all at once he was aware of the truth, and fell on his knees, and Sir Richard too-- "And so did all the wild outlaws, When they saw them kneel. 'My lord, the King of England, Now I know you well!'" Thus he submitted himself, craving the king's mercy for him and his men. The king graciously forgave them all, on condition that Robin gave up this lawless life and went back with him to take service at the court. Robin dutifully consented; then, the king and his knights having exchanged their monkish disguise for more seemly garments of Lincoln green, they all rode together to Nottingham, shooting by the way "pluck. buffet," and neither king nor outlaw spared each other if it were the mischance of either to stand a hearty cuff. When they arrived, the townspeople were alarmed to see so many green coats, thinking the king had been killed and that Robin Hood now came to sack the town. "Full hastily they began to fly,

Both yeomen and knaves, And old wives that might evil go, They hopped on their staves. "The king laughed full fast, And commanded them again; When they saw our comely king, I wish they were full fain." In short, all was now mirth and revelry at Nottingham, where the king in turn feasted his guests. Sir Richard got his lands again, and Robin Hood went up to London to dwell at the court. But here the doughty woodsman was like a bird in a cage. He pined after his free forest life; he could not feel at home where he might not hunt for his own dinner. He spent all his money with the open hand which came readily to one who had been so long in the way of replenishing his treasury by robbing a rich monk or two. His men fell away from him when he could no longer keep them. And at length, when he had lived at court little over a year the chance sight of some young archers shooting one day reminded him how he had once been accounted the best bowman in England; and he could no longer restrain his longing for the greenwood and the chase. Making excuse to the king of a pilgrimage, and getting leave to stay away no more than seven days, he stole back to his old haunts for good and all. The first thing he did was to kill a deer; then he put his horn to his mouth, and at the well remembered sound all the outlaws of the forest quickly gathered together, and ere long "Seven score of right young men Came ready in a row." With them he lived henceforth under the greenwood tree as of old, shooting the king's deer, and defying the king's officers--nay, paying no heed to the king's own command. No one durst meddle with him in the heart of the forest; and there he might have lived on many a year, but that he was beguiled by a monk, as some say, or as others tell, by a woman, and that of his own kin. For Robin growing old, found his eye and hand failing him, so knew that he had fallen ill, and must seek the help of some cunning leech, such as were priests and nuns in those days. He betook himself, then, to the nunnery at Kirkley, of which his cousin was Prioress, and begged her to bleed him for his health's sake. But the false nun, set on to it by his enemies, was minded to bleed him to death who had so trusted himself in her hands. She locked him up in a private chamber, and let the vein run till next day at noon. In vain he tried to escape by the window; his strength was all ebbing away; he could do no more than blow three weak blasts on his bugle horn. The faithful Little John heard from the forest, and knew his call--knew, too, by its feebleness that Robin must be near death. He hastened to Kirkley, where "he broke locks two or three," and made his way into that chamber in which Robin lay helpless. At the sight of his dying master, Little John fell on his knees, begging, in wrath and sorrow, for leave-- " 'To burn fair Kirkley Hall, And all their nunnery.' " 'Now nay, now nay,' quoth Robin Hood;

'That boon I'll not grant thee; I never hurt woman in all my life, :Nor man in woman's company. " 'I never hurt fair maid in all my time, Nor at my end shall it be. But give me my bent bow in my hand, And a broad arrow I'll let flee; And where this arrow is taken up, There shall my grave digg'd be. " 'Lay me a green sod under my head, And another at my feet; And lay my bent bow by my side, Which was my music sweet; And make my grave of gravel and green, Which is most right and meet.'" So died Robin Hood, as he had lived, and so was buried, many there were to say a prayer over his and grave. "For he was a good outlaw, And did poor men much good." Click to continue to the next chapter of Tales Told in Twilight.

|