|

Click Here to return to Boston Illustrated Content Page Click Here to return to Previous Chapter |

(HOME) |

|

Click Here to return to Boston Illustrated Content Page Click Here to return to Previous Chapter |

(HOME) |

|

II. THE NORTH END.

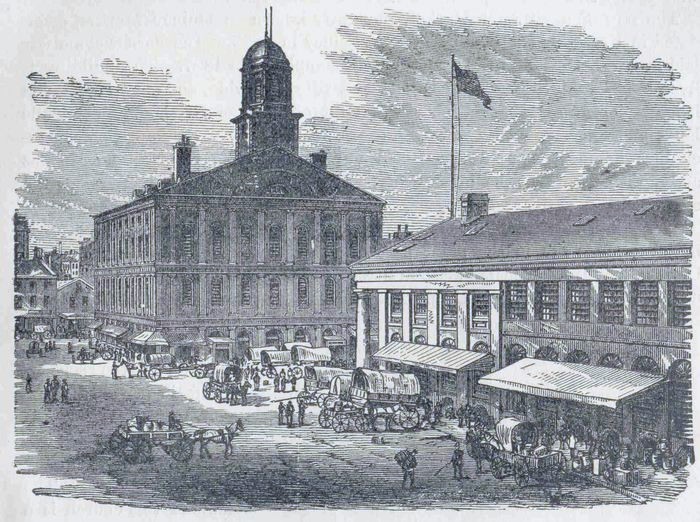

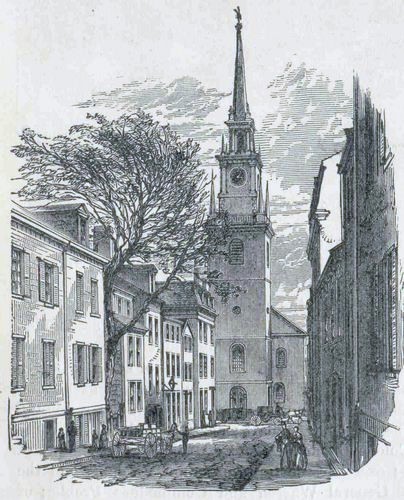

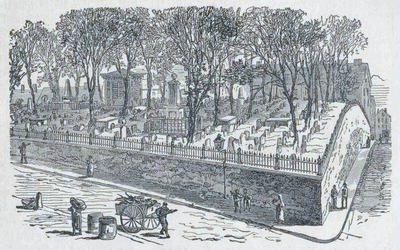

THE extension of the limits of Boston, and the movement of business and population to the southward, have materially changed the meaning attached to the term North End. In the earliest days of the town, the Mill Creek separated a part of the town from the mainland, and all to the north of it was properly called the North End. For our present purpose we include in that division of the city all the territory north of State, Court, and Cambridge Streets. This district is, perhaps, the richest in historical associations of any part of Boston. It was once the most important part of the town, containing not only the largest warehouses and the public buildings, but the most aristocratic quarter for dwelling-houses. But this was a long time ago. A large part of the North End proper has been abandoned by all residents except the poorest classes. Among its important streets may be mentioned Commercial, with its solidly built warehouses, and its great establishments for the sale of grain, ship-chandlery, fish, and other articles; Cornhill, once the head-quarters of the book-trade, a remnant of the business still lingering there; the streets radiating from Dock Square crowded with stores for the sale of cutlery and hardware, meats, wines, groceries, fruit, tin, copper, and iron ware, and other articles of household use; and Hanover, widened in 1869, and now as formerly a great market for cheap goods of all descriptions. Elsewhere in this district are factories for the production of a variety of articles, from a match to a tombstone, from a set of furniture to a church bell. There are but a few relics remaining of the North End of the olden time. The streets have been straightened and widened, and many of them go under different names from those first given them, while most of the ancient buildings have fallen to decay and been removed. Among such as are still left, the most conspicuous and the most famous is old Faneuil Hall, the “Cradle of Liberty.” This building was a gift to the town by Mr. Peter Faneuil. For more than twenty years before its erection the need of a public market had been felt, but the town would never vote to build one. In 1744) Mr. Faneuil offered to build a market at his own expense, and give it to the town, if a vote should be passed to accept it, and keep it open under suitable regulations. This offer was accepted by the town, after a hot discussion, by a narrow majority of seven. The building was erected in 1742; and only five years later the opposition to the market-house system was so powerful that a vote was carried to close the market. From that time until 1761 the question whether the market should be open or not was a fruitful source of discord in local politics, each party to the contest scoring several victories. In the last-named year Faneuil Hall was destroyed by fire. This seems to have turned the current of popular opinion in favor of the market, for the town immediately voted to rebuild it. In 1805 it was enlarged to its present size. From the time the Hall was first built until the adoption of the city charter in 1822, all town meetings were held within its walls. In the stirring events that preceded the Revolution it was put to frequent use. The spirited speeches and resolutions uttered and adopted within it were a most potent agency in exciting the patriotism of all the North American colonists. In every succeeding great crisis in our country’s history, thousands of citizens have assembled beneath this roof to listen to the patriotic eloquence of their leaders and counsellors. The great Hail is peculiarly fitted for popular assemblies. It is seventy-six feet square and twenty-eight feet high, and possesses admi-. ruble acoustic properties. The floor is left entirely destitute of seats, by which means the capacity of the hail, if not the comfort of audiences, is greatly in-creased. Numerous large and valuable portraits adorn the walls: a copy of the full-length painting of Washington, by Stuart; another of the donor of the building, Peter Faneuil, by Colonel Henry Sargent; Healy’s great picture of Webster replying to Hayne; excellent portraits of Samuel Adams and the second President Adams; of General Warren and Commodore Preble; of Edward Everett, Abraham Lincoln, and John A. Andrew; and of several others prominent in the history of Massachusetts and the Union. The Hall is never let for money, but it is at the disposal of the people whenever a sufficient number of persons, complying with certain regulations, ask to have it opened. The city charter of Boston, which makes but very few restrictions upon the right of the city government to govern the city in all local affairs, contains a wise provision forbidding the sale or lease of this Hall.  Faneuil Hall and Quincy Market. The new Faneuil Hall Market, popularly known as Quincy Market, originated in a recommendation by Mayor Quincy in 1823. The corner-stone was laid in April, 1825, and the structure was completed in 1827. The building is five hundred and thirty-five feet long and fifty feet wide, and is two stories in height. This great market-house was built at a cost of $150,000, upon made land; and so economically were its affairs managed that the improvement, including the opening of six new streets and the enlargement of a seventh, was accomplished without the levying of any tax, and without any increase of the city’s debt. The oldest church building in the city and one of the oldest of the historic burial-grounds are in the older part of the North End district. These are Christ Church, Episcopal, on Salem Street, and the old North Burying-Ground, near by, in what remains of Copp’s Hill. Christ Church was established in 1723, and the present is the first and only building ever occupied by the society. During the Revolution, the rector, the Rev. Mather Byles, Jr., left the town on account of his sympathy with the royal cause. The steeple of this church is a prominent landmark. It is, however, but a copy of the original steeple, from which the warning lights were hung on the night of April 18, 1775, which was blown down in the great gale of October, 1804. The tower contains a fine chime of eight bells, upon which have been rung joyful and mournful peals for more than a century and a quarter. The interior of the church is quaint and most interesting. Upon the walls are some historic paintings and mural ornaments; and the church possesses plate, pulpit bible and service books presented by George II., and other valuables. It has a bust of Washington, the first ever made. It has also a rare old christening-bowl. One portion of the gallery was once set apart for slaves.  Christ Church, Salem Street The old North Burying-Ground was the second established in the town. It has for many years been closed against interments, but has been faithfully cared for as a cherished old landmark. Its original limits, when first used for interments in 1660, were much smaller than now. Like most of the remaining relics of the early times, this burial-ground bears traces of the Revolutionary contest. The British soldiers occupied it as a military station, and used to amuse themselves by firing bullets at the gravestones. The marks made in this sacrilegious sport may still be discovered by careful examination of the stones. One of these most defaced is that above the grave of Captain Daniel Malcolm, which bears an inscription speaking of him as:

“A TRUE SON OF LIBERTY A FRIEND TO THE PUBLICK AN ENEMY TO OPPRESSION AN

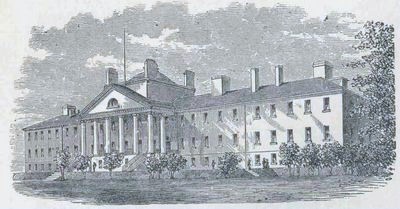

ONE OF THE FOREMOST IN OPPOSING THE REVENUE ACTS ON AMERICA.”  Copp’s Hill Burying-Ground. This refers to a bold act of Captain Malcolm, in landing a valuable cargo of wines, in 1768, without paying the duty upon it. The performance was in the night under the guard of bands of men armed with clubs. It would be called smuggling at the present day, but when committed it was deemed a laudable and patriotic act, because the tax was regarded as unjust, oppressive, and illegal. The most noted persons whose bodies repose within this enclosure were undoubtedly the three Reverend Doctors Mather, — Increase, Cotton, and Samuel; but there are many curious and interesting inscriptions to read, which would well repay a visit. The burying-ground is even now a favorite place of resort in the warmer months, and the gates stand hospitably open to visitors. Strangers will find the superintendent courteous and willing to give information regarding the older gravestones and the most noteworthy graves. It is to the credit of the city, that, when it became necessary in the improvement of this section of the city to cut down Copp’s Hill to some extent, the burying-ground was left untouched, and the embankment protected by a high stone-wall. Quite at the other extreme of the North End district is the Massachusetts General Hospital, a structure of imposing appearance devoted to most beneficent uses. This institution had its origin in a bequest of $ 5,000 made in 1799, but it was not until 1811 that the Hospital was incorporated. The State endowed it with a fee-simple in the old Province House, which was subsequently leased for a term of ninety-nine years; and the Massachusetts Hospital Life Insurance Company was required by its charter to pay one third of its net profits to the Hospital. Large sums of money were raised by private subscription both before the institution had begun operations and every year since. The handsome granite building west of Blossom Street was completed in 1821. In 1846 it was enlarged by the addition of two extensive wings, and in 1875 four new pavilion wards were completed. The stone of the original structure was hammered and fitted by the convicts at the State Prison. The system on which this noble institution is managed is admirable, in that it is so designed as to combine the principles of gratuitous treatment and the payment of their expenses by those who are able to do so. The Hospital turns away none who come within the scope of its operations, while it has room to receive them, however poor they may be. It has been greatly aided in this work by generous contributions and bequests. The fund permanently invested to furnish free beds amounts to over $ 600,000; and the annual contributions for free beds support about 100 at $100 each. To all who are able to pay for their board and for medical treatment the charges are in all cases moderate, never exceeding the actual expense. The general fund of the Hospital is about $1,100,000, and the total of restricted funds attains the same amount. The annual income is a quarter of a million dollars, which is usually slightly in excess of the expenses. These figures are for the Hospital proper and for the McLean Asylum for the Insane at Somerville, which is a branch of the institution. A Training School for Nurses in connection with the Hospital and a Convalescent’s Home in Belmont complete the equipment. From 3,000 to 3,500 patients are treated yearly, of whom more than three-fourths pay nothing. Besides these who are admitted to the Hospital, there are annually from 16,000 to 20,000 out-patients, who receive advice and medicine, or surgical or dental treatment. It will show more clearly how great good is done precisely where it is most needed, if we say that three-fourths of the male patients are classed as mechanics, laborers, teamsters, seamen, and servants; and more than half the female patients are seamstresses, operatives, and domestics.  The Massachusetts General Hospital. |