| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2011 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

|

CHAPTER

X.

Adieu

to Yokuhama Views of Mount Fusi The Kino Channel and Inland

Sea Presents for the Queen The port of Hiogo and town of

Osaca Important marts for trade Good anchorage Crowds of

boats Islands Charming scenery Daimios' castles Towns

and villages Gorgeous sunset Village of Ino-sima Terraced

land "The pilot's home" River-like sea Scenes

on shore Clean and comfortable houses Fortress of Meara-sama

Visit of officials Their manners and customs Gale of wind

Extraordinary harbour Southern Channel Ship ashore Two

Jonahs on board Nagasaki in winter Arrival at Shanghae

Plants shipped for England.

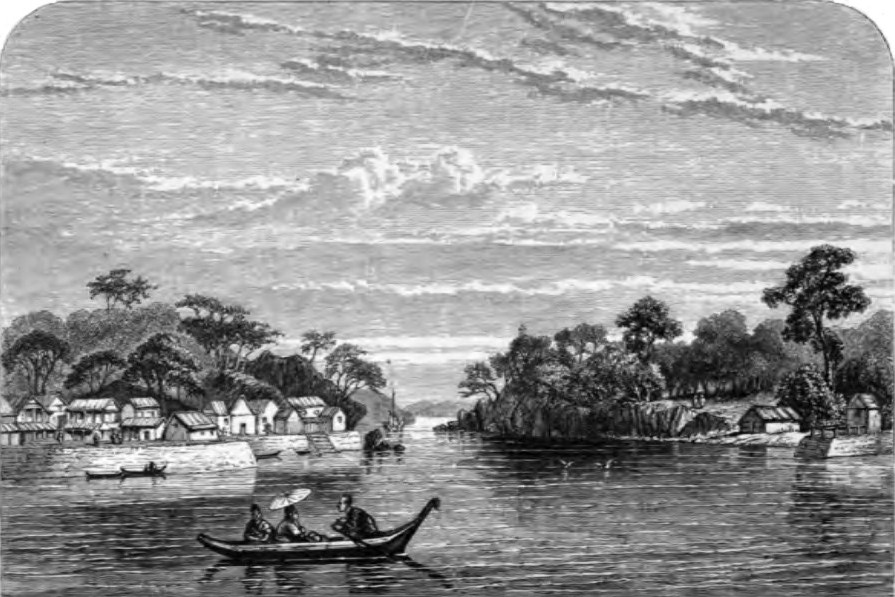

ON the 17th of December, 1860, the good steamship 'England,' in which I was passenger, weighed anchor and proceeded to sea. The wind, which had been blowing a gale the day before, was now light and fair, so that we were able to crowd on all sail and made rapid progress. The headlands which had lately been christened as "Mandarin Bluff" and "Treaty Point," were soon passed, and the pretty little towns of Yokuhama and Kanagawa were lost to our view in the distance. In the afternoon we passed Cape Sagami and the volcanic islands at the entrance of the Bay of Yedo, and were once more in the great Pacific Ocean. Cape Idsu that stormy cape, the dread of mariners, but which, I am bound to say, has as yet treated me kindly was also passed, and then darkness set in, and the fair land of Nipon was hidden from our eyes. On the following morning I was up and on deck before sunrise, and was well rewarded by the beauty of the scene. Landward, Fusiyama, or the "Holy Mountain," was seen towering high above all the other land, covered with snow of the purest white, and its summit already basking in the rays of the morning sun, although that luminary had not yet shown himself to the denizens of our lower world. Sailors and passengers alike looked often and long upon that lovely mountain, and it was with regret we watched it gradually disappear from our view and sink in the horizon. In the afternoon of this day we were abreast of Cape Oo-sima, and soon afterwards entered the Kino Channel, which lies between the islands of Sikok and Nipon, and leads into the Inland Sea. A reference to the map of Japan will give a better idea of the position of this sea than any description. No foreign vessel, except ships of war or transports, had been allowed to navigate its waters, and, as it had not been surveyed, it was necessary, in all cases, to obtain pilots from the Japanese Government before attempting the passage. The 'England' was not a ship of war nor in any way connected with the Government, and, in ordinary cases, would not have been permitted to pass through the sacred waters of the Inland Sea. But as Captain Dundas and his passengers were all anxious to view the beautiful scenery of which they had often heard, a request was sent to the authorities for permission and pilots, backed by the following powerful reasons. Her Majesty the Queen of Great Britain had presented a handsome steam-yacht to the Tycoon of Japan, and the latter had made a selection of lacquer-ware, paper screens, swords, and a variety of other articles, to send to Her Majesty in return. Now, although the good ship 'England' was not a "man of war," and had no great warrior amongst her crew and passengers, yet she had on board the presents for the Queen, and on that account was surely entitled to all the honours of a ship of war. Besides, she might be wrecked if exposed to the stormy waters of the North Pacific Ocean, the presents might be damaged or lost, and that was an additional reason why she ought to be allowed to take the smooth-water passage. The propriety and prudence of the course suggested was perceived at once by the authorities, and pilots were granted forthwith. As the night was calm and clear, we steamed onwards slowly, and found ourselves in the morning on the eastern side of the island of Awadji, or Smoto as it is called in some English charts. There is a passage on the south-east side of this island, but in its centre is a dangerous whirlpool, which all mariners carefully avoid. We therefore took the northern passage. As daylight was breaking the ship got ashore on a bank of soft mud. Our Japanese pilots appeared to be steering right on to the island, thinking, no doubt, that the wonderful English vessel, that went along without sails or paddles, could pass over land and villages as easily as she could plough the waters of the deep sea. Without much difficulty we got the ship afloat again, and proceeded on our voyage, but our confidence in the knowledge of our pilots was considerably lessened. Going onward in a northwesterly direction, we approached the entrance to the bay of Hiogo and Osaca. This beautiful Inland Sea was greenish in colour and smooth as a mill-pond. In the direction of the towns just mentioned it was studded with the white sails of small junks, showing that this portion of the Japanese islands must be densely populated. Fishing-boats were seen in all directions busily employed in securing food for the teeming population; and pleasant-looking villages and Daimios' castles were observed scattered along the shores of the bay. The town of Hiogo, which is the seaport of the imperial city of Osaca, is one of the ports which, according to the treaty, should be opened to foreign trade in 1863; and from all accounts it is likely to prove the most important place in Japan. Kζmpfer, who passed through Osaca about 170 years ago, tells us that he found it "extremely populous, and, if we can believe what the boasting Japanese tell us, can raise an army of eighty thousand men among its inhabitants. It is the best trading town in Japan, being extraordinarily well situated for carrying on commerce, both by land and water. This is the reason why it is so well inhabited by rich merchants, artificers, and manufacturers. . . . Whatever tends to promote luxury, or to gratify sensual pleasures, may be had at as easy a rate here as anywhere, and for this reason the Japanese call Osaca the universal theatre of pleasures and diversions. Plays are to be seen daily, both in public and private houses; mountebanks, jugglers who can show artful tricks, and all the raree-show people who have either some uncommon or monstrous animal to exhibit, or animals taught to play tricks, resort thither from all parts of the empire, being sure to get a better penny here than anywhere else." In proof of this demand for luxuries in Osaca, Kζmpfer tells us that the Dutch East India Company "sent over from Batavia, as a present to the Emperor, a casuar, a large East India bird who would swallow stones and hot coals. This bird having had the ill luck not to please our rigid censors the governors of Nagasaki, and we having thereupon been ordered to send him back to Batavia, a rich Japanese assured us that, if he could have obtained leave to buy him, he would have willingly given a thousand taels for him, as being sure, within a year's time, to get double that money by showing him at Osaca." Hiogo and Osaca were visited by Mr. Alcock in the summer of 1861, and his despatch to Earl Russell fully confirms Kζmpfer's account. "The approach to Hiogo is good and easy, the anchorage secure; the navigation to Osaca for cargo-boats short and easy also, not more than four or five miles from the bay, though some fifteen from Hiogo, which is to Osaca what Kanagawa is to Yedo. Only this last is a capital filled chiefly with Daimios and their retainers dominant classes, which consume much and produce nothing, and are decidedly hostile to foreign commerce, as diminishing their own share and endangering its easy and secure appropriation; while Osaca is a great mercantile centre, situated on a plain intersected by twenty branches of a river, and spanned by innumerable bridges, some of them 300 paces across; with this great advantage (above all others) over Yedo, that, although an imperial city, it is comparatively free from the two-sworded generation of locusts and obstructives. There are a large number of Daimios' residences, occupying more than a league of the river's banks, but I fancy these are seldom occupied, or only temporarily, by their owners. Immense activity reigns everywhere; and although it was difficult to make much way in finding out the true prices, with yakoneens whose business it was to mislead us and fill their own pockets, I saw enough to satisfy myself that, if anything like free interchange could once be established, this would supply a market more than equal in importance to all the other ports combined." It would appear, therefore, that the towns of Hiogo and Osaca are likely to be places of considerable importance in a mercantile point of view. In situation these towns possess great advantages. They are in the central and most populous part of the empire, are easily approached from the sea, and there is good anchorage for ships in Hiogo Bay, or the Gulf of Osaca. Moreover, Osaca is only a day's journey from Miaco, the residence of the spiritual Emperor, and the sacred capital of Japan. Thunberg left Osaca by torchlight in the morning, and reached Miaco the same evening. He says, "Except in Holland, I never made so pleasant a journey as this with regard to the beauty and delightful appearance of the country. Its population, too, and cultivation, exceed all expression. The whole country on both sides of us, as far as we could see, was nothing but a fertile field; and the whole of our long day's journey extended through villages, of which one began where the other ended." These ports are not only placed in a most favourable position for commerce, but they also swarm with merchants; and they have few of those idle, two-sworded gentry, who are the curse of Yedo, and who will render that capital unsafe as a residence for foreigners certainly during the lives of the present generation. The great tea-producing districts of Japan are also situated in this part of the country, a circumstance which will render these ports of considerable value to the foreign merchant. In fact, if we can rely upon the statements of Kζmpfer, Thunberg, and other travellers and their statements would seem to be confirmed in Mr. Alcock's despatch which I have just quoted Osaca appears to be to Japan what Soo-chow was to China in the days before the rebellion, and what it may one day become again namely, the great emporium of trade and luxury. As we were not at this time bound for Hiogo or Osaca, we did not proceed further up the bay, but, bearing southward through a narrow strait between the islands of Awadji and Nipon, we soon reached a wider part of the sea. As we steamed along, the scenery was very lovely and enjoyable. A calm and glassy sea was skirted on each side by hills of various heights from 800 to 2000 feet, sometimes apparently rugged and barren, and sometimes covered with trees and brushwood. Thick clouds of morning mist rested here and there for a while amongst the hills and sometimes on the water, and then became dispersed, allowing us to view the charming scenery, which for a time had been obscured. Fishing-boats were swarming in all directions, and their pretty white sails added not a little to the beauty of the scenery. The excitement experienced by the passengers, and even by the sailors, was something most unusual; sketch-books, pencils, and journals were all in great request, and impressions were produced upon us all which will not easily be forgotten. We were now in what is called the Harama-nada Sea. It gradually widens until the distance between the two shores that is, between the islands of Nipon and Sikok is about thirty miles. Our course lay nearer the eastern than the western side of the passage. In the afternoon we came to a group of islands, through which we sailed until the evening. Some of these are remarkable for their peculiar forms. One named Ya-sima had a rocky summit, giving it the appearance of a huge camel kneeling to receive its load. Viewed from a different point, it looked like the ruins of an ancient castle. Another, called the Che-se-Fusi, or Little Fusiyama, was a remarkable representation, although in miniature, of its snow-capped namesake. Both these islands will no doubt prove valuable landmarks to mariners in this sea, as they have probably been for ages past to the Japanese. The scenery in this part of the sea was quite a panorama ever shifting as we sailed onwards. Now we opened up a beautiful bay, with a fishing village on its shores, and terraced cultivation extending a short way up the side of the hills. Losing sight of this, other islands, bays, and coves came constantly into view to charm and delight the eye. In one flat valley on our left we had a good view of a town of considerable size, in which a Daimio of great power resided and reigned supreme. His castle appeared to be strongly fortified, and had numerous watch-towers on its walls. These castles are apparently numerous in all parts of the empire, for many of them were seen on the shores of the "Inland Sea" during our passage through it. Although the scenery through which we had passed had been most picturesque and beautiful, yet the land did not appear to be rich or fertile. With the exception of little patches of terraced-work near the sea-shore, the ground seemed in a state of nature where the hand of the agriculturist had never ventured to turn over the soil. Rocks, apparently of granite and clay-slate, with red barren earth, were seen everywhere in patches amongst the scanty vegetation of stunted fir-trees. Perhaps in spring, or during the rainy season, when the hills are green, these islands may not present such a barren appearance; and no doubt, as in China, the interior may be rich and fertile, although the land is barren near the sea-shore. But though not rich in an agricultural point of view, the strange and romantic hills and valleys, the rugged rocks, and those sights of nature "stern and wild," contrasted with towns and villages nestled in snug coves, and basking on the shores of this beautiful "Inland Sea," made more than one of our little party express a wish to be set on shore, and to become a "hermit of the glade" for the remainder of his days amongst such scenery. I was rather disappointed in the number of trading-junks and fishing-boats seen during the day. The weather was fine, and there was nothing to keep them in their anchorages near the shore had they really existed. A place like this in China would have swarmed with them; and, as I have already stated, they were numerous in the vicinity of the ports of Hiogo and Osaca towns which we know to be large and populous. This fact, together with the sterile character of the land, would lead to the conclusion that the southern part of Nipon, and the western part of Sikok, do not possess a large population or an extensive trade. Time will show whether these surmises are correct, or whether this absence of marine traffic be due to some other cause. There are numerous well-sheltered anchorages in many parts of this sea; but, as in China, there seem to be some special ones which alone the natives are accustomed to use, to the total neglect of the others, and no doubt for native craft these are the best ones. We passed one of these favoured places about three o'clock in the afternoon, and our pilot wanted the captain to go in there and anchor for the night. This proceeding, however, did not suit the ideas of Englishmen, who are always in a hurry, and it was intimated to our good pilot that it was too early in the day to anchor, and that we must go on until the evening. Before dark another place was pointed out as a safe anchorage for the night. A fishing-junk was at anchor a short distance ahead of us; and our pilot thought, naturally enough, that there must be good anchorage in her vicinity. But when we got up with the junk, a cast of the lead showed us that she was at anchor in a place where there were twenty-three fathoms of water! She had, no doubt, only a light kedge out, and had taken up that position for fishing operations. We therefore steamed onwards until our soundings gave twenty fathoms, when Captain Dundas, fearing to approach nearer the shore, dropped anchor for the night. A few minutes before we anchored the sun went down behind the islands of the west, and, in bidding the "Inland Sea "adieu for the day, lighted up the clouds in the most gorgeous manner, and gave them the appearance of mountains of fire and gold. And thus ended my first day in the Harama-nada Sea. Next morning (Dec. 20), at daylight, we weighed anchor with considerable difficulty, owing to the length of chain we had out in our deep anchorage. We discovered, too, that, at a short distance from where we had spent the night, there was an excellent anchorage, with only eight fathoms of water over it. During the forenoon we came up with a pretty-looking village of considerable size, named Ino-sima. Here the land appeared much more fertile than we had seen since entering the sea. The houses were scattered over the sides of the hills amongst fields and gardens of terraced land, and surrounded with healthy fruit-trees, apparently pears. The young crops of wheat and barley were above ground, forming broad patches of the liveliest green, most pleasing to look upon. Half-way up the hills cultivation ceased, and beyond all was barren or in a state of nature. One of our pilots informed us that he was a native of this place, and it was sketched immediately and romantically called "The Pilot's Home."  Ino-Sima, "Our Pilot's Home" Our passage during the morning of this day had been straight and broad, and of easy navigation, even for a sailing vessel; but about 1 P.M. we entered a pass between some islands which was certainly not more than half a mile in width. Here the scenery was very remarkable, and perhaps the finest we had yet seen. Pretty villages, temples, and farm-houses were observed on every side of us. Now and then we passed a fertile valley, in a high state of cultivation, stretching far back amongst the hills. The houses, too, seemed to be nicely thatched and tiled, and had an air of comfort and cleanliness about them rarely seen in oriental countries. We appeared to be sailing down some smooth river, which every now and then widened or narrowed according to the formation of the land. Around us there were hills and mountains, of various heights and of every conceivable form. The lowest rose but a few feet above the water, while the highest seemed fully two thousand feet high. Here and there, in our progress, I observed a column of stone erected upon the top of a sunken rock to warn the mariner of the hidden danger. On one of the banks of this river-like sea a broad road was observed skirting the beach under an avenue of trees. Our pilots informed us that this was a portion of the Tokaido, or imperial highway, which leads all the way from Yedo to Nagasaki. Sometimes the sea appeared completely land-locked, and resembled a lake with its bays and inlets; at other times it had the river-like appearance I have already noticed. Some of us compared it to Loch Lomond, Loch Katrine, or the Kiles of Bute; but, although probably it had a partial resemblance to all these places in the Scottish Highlands, yet it had a character peculiarly its own. In the afternoon we had a good view of the castle and fortress of Meara-sama, situated at the head of a deep bay. This castle is said to be remarkable in Japan for its great strength. It is supposed to be one of the strongest in the empire, and perfectly impregnable. A massive sea-wall was built along the sea-shore; while behind this wall were seen castles, turrets, and watchtowers, inhabited by this feudal chief and his numerous retainers. Leaving this bay and its stronghold on our right and to the westward, our course led us in a more southerly direction, the channel still narrow and winding. This part continued as populous as that which I have already noticed when we entered the "narrows," and large villages, composed of comfortable-looking houses not densely packed together, but divided by fields and gardens were everywhere seen along the shores. In the evening we passed out into a wider part of the sea, and anchored for the night at a place called Metari. Boats in large numbers, filled with wondering natives, had been sculling round us to get a sight of the ship that went ahead without wind or sails, and of the strange beings from some far-off foreign land who crowded her deck. While we were sitting at dinner, and speaking of the strange and beautiful scenery through which we had passed during the day, a messenger came on board to inform us that the high officers of the place were coming off to pay us a visit. In a few minutes three quiet, modest-looking individuals were ushered into the cabin, and led up to the head of the table, where Captain Dundas was seated. They wanted to know whence we came, what we wanted, and whither we were bound all of which questions, with many others, were answered to their entire satisfaction. They were then politely offered wine, biscuits, and sundry other things which were upon the table. Each of them tasted what was set before him, and then, pulling out a piece of paper, wrapped up in it the remainder of the solids, and thrust the parcel into his wide sleeve. Such is the custom of the country, and such is termed politeness in Japan. A numerous retinue of servants attended these high officials, all of whom were delighted with what was given to them, and begged for more! As these gentry took their departure, they intimated to us that an officer of a yet higher rank than theirs was coming on board. This personage presented himself soon afterwards, and, giving his swords to an attendant, walked up to the head of the table as the others had done. The ceremony of questioning, drinking, eating, and pocketing was gone through a second time, and then, with many low bows and expressions of thanks, the great man and his attendants took their departure for the shore. Dec. 21st. We weighed anchor this morning as usual at daylight. We were now in what is called the Suwo-nada Sea. It is wide, has few islands, and is connected with the Pacific Ocean by a wide passage known as the Bun-go Channel. We were too far from the land to note anything worthy of interest on its shores. This sea is chiefly remarkable for gales of wind of great violence, owing, probably, to the Bun-go Channel forming a sort of funnel between this Inland Sea and the Pacific Ocean. We were destined to experience one of these gales on the present occasion. It commenced in the morning, and by the afternoon had increased to a hurricane. The wind was not steady, but came down in fearful gusts, strong enough, almost, to blow any one overboard who ventured on the poop of the vessel. A trysail, which had been set, was riven from the sheets, and its block shaken with fearful violence and thrown into the sea. The scene reminded me of a powerful bulldog tearing and shaking a cat, and then casting it away in anger when he had deprived it of life. In this state of things the 'England' made but little headway, and it was determined that we should look out for a safe anchorage for the night. We therefore bore up for the mainland of Nipon, to the westward, and made for a place called, in Japanese charts, Kamino-saki. This is a most extraordinary anchorage, and well worth the attention of those who navigate this sea. As we approached the land there seemed to be no shelter except an open bay, protected indeed by the land on the west, but fully exposed to the eastward. On nearing the shore, however, we observed an opening on our left, not more than sixty yards wide, which looked at first sight almost artificial, but was merely natural nevertheless, and which led into a beautiful land-locked harbour. We steamed through this narrow passage, and anchored in thirteen fathoms water. The place in which we now were had all the appearance of an inland lake, and was protected from the wind in all directions. On each side of us two small towns were observed, pleasantly situated on the banks of the lake, and forming little crescents along its shores. The houses had whitewashed walls, and appeared to be clean and comfortable looking buildings. Little temples also appeared on the hill-sides, surrounded by pine-trees; and Buddhist priests were seen about the doors. Hills filled the background, well-wooded in some parts, and terraced in others all the way up to their summits, showing that here the soil was fertile and productive. Pinus Massoniana seemed to be the most common timber-tree in this quarter. On our approach the whole of the inhabitants of these quiet and secluded villages came out of their houses to look at the strange He-funy, or fire-ship; but the water being rather rough, the wind tempestuous, and night closing in, none of them ventured off from the shore. This evening we were therefore allowed to dine in peace, and were not honoured with the presence of yakoneens and other "high officers" at our table. Next day our progress was slow, as the gale was still blowing, and we anchored about eight o'clock in the evening. At daylight on the following morning the Southern Strait, which leads out of the Inland Sea into the Corea Strait and China Sea, was visible ahead of us, and distant some ten or twelve miles. A large fleet of junks and boats was seen coming out from the strait, having, no doubt, taken shelter during the gale of the previous days. The entrance to this strait is about half a mile in width; it is bounded on the north by the southern end of Nipon, and on the south by Kiu-siu. Two small towns, one on each side, were visible on its shores. As we passed along, the strait widened considerably; and a large town, named Simone-saki, was observed on our right hand. A little further on, to the left, the residence of a Daimio named Korkura was pointed out, and we met that worthy himself in a painted barge, going in the direction of Simone-saki. The scenery in the vicinity of the strait is hilly, the hills being often conical in form, and covered with trees and brushwood. Generally the country has that barren and uncultivated character which I have already often alluded to in describing our voyage down this sea. It presents a striking contrast to the volcanic regions near Yedo, where every inch of land is capable of being profitably cultivated, although, for some reason, thousands of acres are lying waste, or covered with brushwood of little value. But although the shores of the Inland Sea, beautiful though they are, present a barren aspect to the voyager, yet there must be many rich valleys amongst these hills capable of producing abundant crops to supply "the wants of man and beast." Glimpses of these were caught as we sailed along the shores, and there must have been many more which were hidden from our view. These the streams which flow down from the mountains irrigate and fertilise, while the climate of Japan is probably one of the finest in the world. Before we got clear of the strait some alarm was felt owing to the shallowness of the water, and it must be confessed we had no great confidence in the knowledge of our pilots. After having had for some time only three and three-and-a-half fathoms of water, we suddenly felt an unusual motion, which old sailors like myself knew to be an intimation from the ship that she was "hard and fast ashore." And so it was; we had touched a bank having only two fathoms of water on it, which our good ship refused to go over, and from which she could not recede. Our Japanese pilots took the matter very coolly, and told us we should have to remain in our present position until the tide rose, when we should have water enough. This was all very well, and it turned out quite true; but what if one of those sudden gales for which this coast is famous had come on in the mean time! We had no fear for our lives, as we might easily have reached the shore in boats, but my beautiful collection of plants, which was on board, I certainly looked upon as being in the greatest danger. While matters looked rather gloomy, a good-natured gentleman came up to me, and "hoped my collections were insured!" Although the circumstances in which we were placed at this time were far from being pleasant, we could not resist having a good joke with two of our fellow-passengers. Dr. and Mr. had both been unfortunate at sea, and had related, during our voyage, the stories of their various shipwrecks. On more than one occasion they had been told that we held them responsible for any ill-luck that might befall us during the present voyage; that both of them were evidently Jonahs; and that, if we chanced to get into danger, they must be prepared to go overboard in order to ensure the safety of the ship. When, therefore, all our efforts to get into deeper water appeared fruitless, and when the 'England' began to bump uncomfortably on the ground, an intimation was conveyed to these gentlemen that their time had come, and that they had better prepare for the fatal plunge. The sacrifice, however, was not required, as the tide rose before we could carry out our benevolent intentions, and the vessel floated safely into deeper water. As we had now passed out of the Inland Sea, Captain Dundas determined not to trust the native pilots any longer, and kept well out from all the dangers of the coast. It was now bitterly cold, and the tops of all the hills were covered with snow. We encountered another gale of wind when off the Gotto Islands, and reached the quiet little harbour of Nagasaki without any further adventures, all of us highly pleased with our voyage through the Inland Sea. As the 'England' remained three days at Nagasaki, I employed the time in visiting a number of places in the vicinity, and added several novelties to my collections. The face of the country had undergone a great change since my former visit. It was now winter; deciduous trees were leafless, the rice-lands were lying fallow, and the hill-sides were green with the young crops of wheat and barley. The dress of the people had changed with the season; and the children, instead of being carried on the backs of children as before, were now borne about on their bosoms. As my Ward's cases were all quite full, it was necessary to pack the Nagasaki plants in baskets, and these were put away in the long-boat on the starboard side of the ship. On the 29th of December we bade adieu, for the present, to the pleasant shores of Japan, and sailed for China. A short time after we had put to sea I felt some regret at not having put my plants in the boat on the port side, which, being to leeward, was less exposed to spray from the sea. It was lucky, as it turned out, that no alteration was made, for on the following day we encountered a heavy gale of wind; the ship rolled dreadfully; and a quantity of planks piled on the house in midships gave way, and carried the long-boat, that hung on the port side, headlong into the sea! On the 2nd of January we arrived at Shanghae, where I was kindly received by Mr. Webb, the worthy successor of my old friend the late Mr. Beale. My time was now fully occupied in repacking and preparing the plants for the long voyage which was yet before them. The most important portion was confided to the care of Captain Taylor, of the ship 'Tung-yu,' who, a short time before this, had had the honour to introduce into Europe the living salamander now in the gardens of the Zoological Society of London. Captain Taylor delivered these plants in the most excellent condition. Some of them were exhibited before the Horticultural Society, at South Kensington, three days after their arrival in England; and it was remarked that they looked as if they had been luxuriating all their lives in the pure air of Bag-shot, instead of having just been landed from a sea voyage of sixteen thousand miles. |