| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2008 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click

Here to return to

When Life Was Young At the Old Farm in Maine Content Page Return to the Previous Chapter |

(HOME)

|

CHAPTER

XX

CEDAR BROOMS AND A NOBLE STRING OF TROUT It was a part of Gram's

household creed, that the

wood-house and carriage-house could be properly swept only with a cedar

broom.

Brooms made of cedar boughs, bound to a broom-stick with a gray tow

string,

were the kind in use when she and Gramp began life together; and

although she

had accepted corn brooms in due course, for house work, the cedar broom

still

held a warm corner in her heart. "A nice new cedar broom is the best

thing

in the world to take up all the dust and to brush out all the nooks and

corners," she used to say to Theodora and Ellen; and when, at stated

intervals, it became necessary, in her opinion, to clean the wood-house

and

other out-buildings, or the cellar, she would generally preface the

announcement by saying to them at the breakfast table, "You must get me

some broom-stuff, to-day, some of that green cedar down in the swamp

below the

pasture. I want enough for two or three brooms. Sprig off a good lot of

it and

get the sprigs of a size to tie on good." The girls liked the trip, for it

gave them an

opportunity to gather checkerberries, pull "young ivies," search for

"twin sisters" and see the woods, birds and squirrels, with a chance

of espying an owl in the swamp, or a hawk's nest in some big tree; or

perhaps a

rabbit, or a mink along the brook. If they could contrive to get

word of their trip to

Catherine Edwards and she could find time to accompany them, so much

the more

pleasant; for Catherine was better acquainted with the woods and

possessed that

practical knowledge of all rural matters which only a bright girl, bred

in the

country with a taste for rambling about, ever acquires. A morning proclamation to gather

broom-stuff having

been issued at about this time, the three girls set off an hour or two

after

dinner for the east pasture; Mrs. Edwards, who was a very kind,

easy-going

woman, nearly always allowed Catherine to accompany our girls. Kate, in

fact,

did about as she liked at home, not from indulgence on the part of her

mother

so much as from being a leading spirit in the household. She was very

quick at

work; and her mother, instead of having to prompt her, generally found

her

going ahead, hurrying about to get everything done early in the day.

Then, too,

she was quick-witted and knew how to take care of herself when out from

home.

Mrs. Edwards always appeared to treat Kate more as an equal than a

daughter.

There are children who are spoiled if allowed to have their own way,

and others

who can be trusted to take their own way without the least danger of

injury,

and whom it is but an ill-natured exercise of authority to restrict to

rules. The Old Squire was breaking

greensward in the south

field that afternoon with Addison and Halse driving the team which

consisted of

a yoke of oxen and two yokes of steers, the latter not as yet very well

"broken" to work. My inexperienced services were not required; but to

keep me out of hurtful idleness, the old gentleman bade me pick up four

heaps

of stones on a stubble field near the east pasture wall. It was a kind

of work

which I did not enjoy very well, and I therefore set about it with a

will to

get it done as soon as possible. I had nearly completed the

fourth not very large

stone pile, when I heard one of the girls calling me from down in the

pasture,

below the field. It was Ellen. She came hurriedly up nearer the wall.

"Run

to the house and get Addison's fish-hook and line and something for

bait!"

she exclaimed. "For there is the greatest lot of trout over at the Foy

mill-pond you ever saw! There's more than fifty of them. Such great

ones!" "Why, how came you to go over

there?" said

I; for the Foy mill-pond was fully a mile distant, in a lonely place

where

formerly a saw-mill had stood, and where an old stone dam still held

back a

pond of perhaps four acres in extent. The ruins of the mill with

several broken

wheels and other gear were lying on the ledges below the dam; and two

curiously

gnarled trees overhung the bed of the hollow-gurgling stream. Alders

had now

grown up around the pond; and there were said to be some very large

water

snakes living in the chinks of the old dam. It was one of those ponds

the

shores of which are much infested by dragon-flies, or "devil's

darn-needles,"

as they are called by country boys, — the legend being that with their

long

stiff bodies, used as darning needles, they have a mission, to sew up

the

mouths of those who tell falsehoods. "Oh, Kate wanted to go," replied

Ellen.

"We went by the old logging road through the woods from the cedar

swamp.

She thought we would see a turtle on that sand bank across from the old

dam, if

we sat down quietly and waited awhile. The turtles sometimes come out

on that

sand bank to sun themselves, she said. So we went over and sat down,

very

still, in the little path at the top of the dam wall. The sun shone

down into

the water. We could see the bottom of the pond for a long way out. Kate

was

watching the sand bank: and so was I; but after a minute or two,

Theodora

whispered, 'Only see those big fish!' Then we looked down into the

water and

saw them, great lovely fish with spots of red on their sides, swimming

slowly

along, all together, circling around the foot of the pond as if they

were

exploring. Oh, how pretty they looked as they turned; for they kept

together

and then swam off up the pond again. "Kate whispered that they were

trout. 'But I

never saw so many,' she said, 'nor such large ones before; and I never

heard

Tom nor any of the boys say there were trout here.' "We thought they had gone

perhaps and would not

come again," Ellen continued. "But in about ten minutes they all came

circling back down the other shore of the pond, keeping in a school

together

just as when we first saw them. We sat and watched them till they came

around

the third time, and then Kate said, 'One of us must run home and tell

the boys

to come with their hooks.' I said that I would go, and I've run almost

all the

way. Now hurry. I'll rest here till you come. Then we will scamper

back." In a corner of the vegetable

garden where I had dug

horse-radish a few mornings before, I had seen some exceedingly

plethoric

angle-worms; and after running to the wood-house and securing a

fish-hook, pole

and line which Addison kept there, ready strung, I seized an old tin

quart, and

going to the garden, with a few deep thrusts of the shovel, turned out

a score

or two of those great pale-purple, wriggling worms. These I as hastily

hustled

into the quart along with a pint or more of the dirt, then snatching up

my

pole, ran down to the field where Nell was waiting for me, seated on

one of my

lately piled stone heaps. "Come, hurry now," said she; and

away we

went over the wall and through brakes and bushes, down into the swamp,

and then

along the old road in the woods, till we came out at the high conical

knoll,

covered with sapling pines, to the left of the old mill dam. There we

espied

Kate and Theodora sitting quietly on a log. "Oh, we thought that you never

would come,"

said the former in a low tone. "But creep along here. Don't make a

noise.

They've come around six times, Ellen, since you went away. I never saw

trout do

so before. I believe they are lost and are exploring, or looking for

some way

out of this pond. I guess they came down out of North Pond along the

Foy Brook;

for they are too large for brook trout. They will be back here in a few

minutes, again. Now bait the hook and drop in before they come back.

Then sit

still, and when they come, just move the bait a little and I think

you'll get a

bite." I followed this advice and sat

for some minutes,

dangling a big angle-worm out in the deep water, off the inner wall of

the dam,

while my three companions watched the water. Presently Theodora

whispered that

they were coming again; and then I saw what was, indeed, from a

piscatorial

point of view, a rare spectacle. First the water waved deep down, near

the

bottom, and seemed filled with dark moving objects, showing here and

there the

sheen of light brown and a glimmer of flashing red specks, as the

sunlight fell

in among them. For an instant I was so intent on the sight, that I

quite forgot

my hook. "Bob it now," whispered Kate, excitedly. I had scarcely given my hook a

bob up and down when,

with a grand rush and snap, a big trout grabbed worm, hook and all.

Instinctively I gave a great yank and swung him heavily out of the

water, my

pole bending half double. The trout was securely hooked, or I should

have lost

him, for he fell first on some drift logs and slid down betwixt them

into the

water again. Seizing the line in my hands, since the pole was too light

for the

fish, I contrived to lift him up and land him high and dry on the dam,

close at

the feet of the girls. "Well done!" Theodora whispered.

"Oh,

isn't he a noble great one, and how like sport he jumps about! Too bad

to take

his life when he's so handsome and was having such a good time among

his

mates!" "Unhook him quick and throw in

again!"

cried Kate. "Be careful he don't snap your fingers. He's got sharp

teeth.

Don't let him leap into the water. That's good! We'll keep him behind

this log.

Now bait again with a good new worm." "But they've gone," said

Theodora.

"They darted away when you pulled this one out. It scared them." I had experienced some

difficulty in disengaging my

hook from the trout's jaw, but at length put on another worm and

dropped in

again, not a little excited over my catch. "I'm afraid they will not come

around

again," said Ellen. Kate, too, thought it doubtful whether we would see

anything more of the school. "I guess they will beat a retreat up to

North

Pond," said she. We sat quietly waiting for eight

or ten minutes and

were losing hope fast, when lo! there they all came again — swimming

evenly

around the foot of the pond in the deep part, as before, winnowing the

water

slowly with their fins. Again I waited till my hook was

in the midst of the

school; and this time I had scarcely moved it, when another snapped it.

I had

resolved not to jerk quite so hard this time; but in my excitement I

pulled

much harder than was necessary to hook the trout and again swung it out

and

against the wall of the dam. With a vigorous squirm the fish threw

himself

clean off the hook; but by chance I grabbed him in my hands, as he did

so, and

threw him over the dam among the raspberry briars — safe. "Well done again," said Theodora. In a trice I had rebaited my

hook and dropped in a

third time; but as before the vagrant school had moved on. They had

seemed

alarmed for the moment by the commotion, and darted off with

accelerated speed.

But we now had more confidence that they would return and again settled

ourselves to wait. "Oh, I want to catch one!"

exclaimed Ellen. "I wish we had more hooks," said

Kate.

"We would fish at different points around the pond." After about the same interval of

time and in the same

odd, migratory manner, the beautiful school came around four times more

in

succession; and every time I swung out a handsome one. Kate then took

the pole

and caught one. Then Ellen caught one; and afterwards Theodora took her

turn

and succeeded in landing a fine fellow which flopped off the dam once,

but was

finally secured. In the scramble to save this last one, however, I

rolled a

loose stone off the dam into the water; and either owing to the splash

made by

the stone, or because the trout had completed their survey of the pond,

they

did not return. We saw nothing more of the school although we had not

caught a

fifth part of them. After waiting fifteen or twenty

minutes we went along

the shore on both sides of the pond but could not discern them

anywheres. It is

likely that they had gone back to the larger pond, two miles distant. At that time, the very odd

circumstances attending

the capture of these trout did not greatly surprise me; for I knew

almost

nothing of fishing. But within a considerable experience since, I have

never

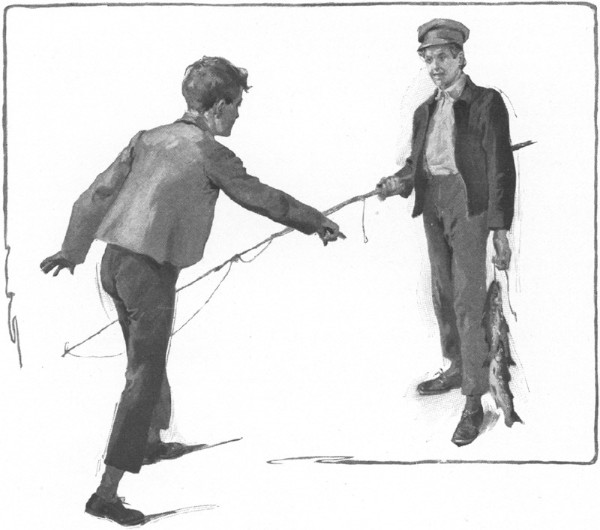

seen anything like it. We laid the nine large trout in

a row on the dam,

side by side, and then strung them on a forked maple branch. They were

indeed

beauties! The largest was found that night to weigh three pounds and

three quarters;

and the smallest two pounds and an ounce. The whole string weighed over

twenty-two pounds. Going homeward, we first took turns carrying them,

then hung

them on a pole for two to carry. Our folks were at supper when we

arrived at the house

door with our cedar and our fish. When they saw those trout, they all

jumped up

from the table. Addison and Halse had never caught anything which could

compare

with them for size; both of the boys stared in astonishment. "Where in the world did you

catch those whopping

trout?" was then the question which we had to answer in detail. Kate carried three of them home

with her; and we had

six for our share. The Old Squire dressed two of the largest; and

grandmother

rolled them in meal and fried them with pork for our supper. I thought

at the

time that I had never tasted anything one half as good in my life! Next morning Addison got up at

half past four and

having hastily milked his two cows, went over to the old mill-pond, to

try his

own hand at fishing there. He found Tom Edwards there already; but

neither of

them caught a trout, nor saw one. Addison went again a day or two

after; and

the story having got abroad, more than twenty persons fished there

during the

next fortnight, but caught no trout. Evidently it was a transient

school. I never caught a

trout in the mill-pond, afterwards; although the following year Addison

made a

great catch in a branch of the Foy stream below the dam under somewhat

peculiar

circumstances. At the far end of the dam, a

hundred feet from the flume,

there was an "apron," beneath a waste-way, where formerly the

overflow of water went out and found its way for a hundred and fifty

yards,

perhaps, by another channel along the foot of a steep bank; then,

issuing

through a dense willow thicket, it joined the main stream from the

flume. Water rarely flowed here now,

except in time of

freshets, or during the spring and fall rains; and there was such a

prodigious

tangle of alder, willow, clematis and other vines that for years no one

had

penetrated it. From a fisherman's point of view there seemed no

inducement to

do so, since this secondary channel appeared to be dry for most of the

time. In point of fact, however, and

unknown to us, there

was a very deep hole at the foot of the high bank where the channel was

obstructed by a ledge. The hole thus formed was thirty or forty feet in

length,

and at the deepest place under the bank the water was six or seven feet

in

depth; but such was the tangle of brush above, below and all about it

that one

would never have suspected its existence. An experienced and observing

fisherman would have

noted, however, that always, even in midsummer, there was a tiny rill

of water

issuing through the willows to join the main stream; and that, too,

when not a

drop of water was running over the waste-way of the dam. He would have

noted

also that this was unusually clear, cold water, like water from a

spring. There

was, in fact, a copious spring at the foot of the bank near the deep

hole; and

this hole was maintained by the spring, and not by the water from above

the

dam. Addison was a born observer, a

naturalist by nature;

and on one of these hopeful trips to the mill-pond, he had searched out

and

found that hidden hole on the old waste-way channel, below the dam.

When he had

forced his way through the tangled mass of willows, alders and vines

and

discovered the pool, he found eighteen or nineteen splendid speckled

trout in

it. Either these trout had come over

the waste-way of the

dam in time of freshet, and had been unable to get out through the rick

of

small drift stuff at the foot of the hole; or else perhaps they were

trout that

had come in there as small fry and had been there for years, till they

had

grown to their present size. Certain it is that they were now two-and

three-pound

trout. Did Addison come home in haste

to tell us of his

discovery? Not at all. He did not even allow himself to catch one of

the trout

at that time, for he knew that Halstead and I had seen him set off for

the old

mill-pond. He came home without a fish, and remarked at the

dinner-table that

it was of no use to fish for trout in that old pond — which was true

enough. The next wet day, however, he

said at breakfast to

the Old Squire, "If you don't want me, sir, for an hour or two this

morning, I guess I'll go down the Horr Brook and see if I can catch a

few

trout." Gramp nodded, and we saw Addison

dig his worms and

set off. The Horr Brook was on the west side of the farm, while the old

mill-pond lay to the southeast. What Addison did was to fish down the

Horr

Brook for about a mile, to the meadows where the lake woods began. He

then made

a rapid detour around through the woods to the Foy Brook, and caught

four trout

out of the hidden preserve below the old dam. Afterwards he went back

as he had

come to the Horr Brook, then strolled leisurely home with eight pounds

of

trout. Of course there was astonishment

and questions.

"You never caught those trout in the Horr Brook!" Halstead exclaimed.

But Addison only laughed. "Ad, did you get those beauties

out of the old

mill-pond?" demanded Ellen. "No," said Addison, but he would

answer no

more questions. About two weeks after that he

set off fishing to the

Horr Brook again, and again returned with two big trout. Nobody else

who fished

there had caught anything weighing more than half a pound; and in the

lake, at

that time, there was nothing except pickerel. But all that Addison

would say

was that he did not have any trouble in catching such trout. The mystery of those trout

puzzled us deeply. Not

only Halstead and I, but Thomas Edwards, Edgar Wilbur and the Murch

boys all

did our best to find out where and how Addison fished, but quite

without

success. Cold weather was now at hand and the fishing over; Addison astonished us, however, by bringing home two noble trout for Thanksgiving day.

THOSE BIG TROUT. The next spring, about May 1st,

he went off fishing,

unobserved, and brought home two more big trout. After that if he so

much as

took down his fish-pole, the rumor of it went round, and more than one

boy made

ready to follow him. For we were all persuaded that he had discovered

some

wonderful new brook or trout preserve. Not even the girls could endure

the grin of superior

skill which Addison wore when he came home with those big trout.

Theodora and

Ellen also began to watch him; and the two girls, with Catherine

Edwards,

hatched a scheme for tracking him. Thomas had a little half-bred cocker

spaniel

puppy, called Tyro, which had a great notion of running after members

of the

family by scent. If Thomas had gone out, and Kate wished to discover

his

whereabouts, she would show him one of Thomas's shoes and say, "Go find

him!" Tyro would go coursing around till he took Thomas's track, then

race

away till he came upon him. The girls saved up one of

Addison's socks, and on a

lowery day in June, when they made pretty sure that he had stolen off

fishing,

Ellen ran over for Kate and Tyro. Thomas was with them when they came

back, and

Halstead and I joined in the hunt. The sock was brought out for Tyro to

scent;

then away he ran till he struck Addison's trail, and dashed out through

the

west field and down into the valley of the Horr Brook. All six of us followed in great

glee, but kept as

quiet as possible. It proved a long, hot chase; for when Tyro had gone

along

the brook as far as the lake woods, he suddenly tacked and ran on an

almost

straight course through the woods and across the bushy pasture-lands,

stopping

only now and then for us to catch up. When we came out on the Foy Brook

at a

distance below the old dam, the dog ran directly up the stream till he

came to

the place where the little rill from the hidden hole joined it; then he

scrambled in among the thick willows. We were a little way behind, and

knowing that the dog

would soon come out at the mill-pond, we climbed up the bank among the

low

pines on the hither side of the brook. Tyro was not a noisy dog, but a

few moments after he

entered the thicket we heard him give one little bark, as if of joy. "He's found him!" whispered

Kate.

"Let's keep still!" Nothing happened for some

minutes; then we saw

Addison's head appear among the brush, as if to look around. For some

time he

stood there, still as a mouse, peering about and listening. Evidently

he

suspected that some one was with the dog, most likely Thomas, and that

he had

gone to the mill-pond to fish; but we were not more than fifty feet

away, lying

up in the thick pine brush. After looking and listening for

a long while, Addison

drew back into the thicket, but soon reappeared with two large trout,

and was

hurrying away down the brook when we all shouted, "Oho!" Addison stopped, looking both

sheepish and wrathful;

but we pounced on him, laughing so much that he was compelled to own up

that he

was beaten. He showed us the hole — after we had crept into the thicket

— and

the ledge where he had sat so many times to fish. "But there are only

four

more big trout," he said. "I meant to leave them here, and put in

twenty smaller ones to grow up." The girls thought it best to do

so, and Halstead and

I agreed to the plan; but three or four days later, when Theodora,

Ellen and

Addison went over to see the hole again, we found that the four large

trout had

disappeared. We always suspected that Thomas caught them, or that he

told the

Murch boys or Alfred Batchelder of the hole. Yet an otter may possibly

have

found it. In May, two years afterward, Halstead and I caught six very

pretty

half-pound trout there, but no one since has ever found such a school

of

beauties as Addison discovered. |