| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2008 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click

Here to return to

When Life Was Young At the Old Farm in Maine Content Page Return to the Previous Chapter |

(HOME)

|

|

CHAPTER

XVIII APPLE-HOARDS We heard a great deal concerning

"Reconstruction" of the Union that summer. The Old Squire was

painfully concerned about it; he feared that Congress had made mistakes

which

would nullify the results gained by the Civil War. The low character of

the

men, sent to the South to administer the government, revolted him. He

used to

bring his newspaper to the table nearly every meal and would sometimes

fling it

down indignantly, crying, "Wrong! wrong! all wrong!" Then he and

Addison would discuss current politics, while the rest of us listened,

Theodora

gravely, Halstead scoffing, and I often very absently, for as a boy I

had other

more trivial interests chiefly in mind. I recall that the old gentleman

used

frequently to exclaim, "You boys must begin to read the Constitution.

Next

after the Bible, the Constitution ought to be read in every family in

our

land." I have to confess that at this

particular time I was

much less interested in the Constitution than in the luscious fall

apples out

in the orchard, and the rivalry to secure them. "Have you got a hoard?" was the

question

which, at about this time, began to be whispered among us. At first the query was a novelty

to me; my thoughts

went back to a story which I had once read concerning a horde of

robbers on the

steppes of Central Asia. In this case, however, the thing referred to

was a

hoard of early apples. I had gone to the Edwardses on some domestic

errand; it

was directly after breakfast, and Thomas, who was putting a new tooth

in the

"loafer rake," had set a fine, mellow "wine-sap," from

which he had taken a bite, on the shed sill beside him. "Got a pile of

those fellows in my hoard," he remarked, with a boastful wink. "Have

you got a hoard down at your house?" "Tom is always bragging about

his hoard,"

said Catherine, who had come to the kitchen door, to hear any news

which I

might have to impart. "He thinks nobody can have a hoard but

himself." "She's got one," Tom whispered

to me, as

Catherine turned away. "She's awful sly about it, for fear I'll find

it,

and I think I know where it is. I'll bet she has gone to it now," he

added, taking another bite; and jumping up, he peeped into the kitchen.

"She has" he whispered to me. "Come on, still;

don't say a word and we will catch her." I remember feeling a certain

faint sense of

repugnance to engaging in a hunt for Catherine's apple preserve; but I

followed

Tom around the wood-shed, past a corn-crib, and then around to the

north side

of the barn. "Now sneak along beside the

stone wall

here," said Tom. "Keep down. Don't get in sight." We crawled along in cover of the

stone wall and came

down opposite the garden and orchard. Tom then peeped stealthily over. "There she is!" he whispered,

"right

out there by the Isabella grape trellis; keep still now, she's going

back to

the house. We'll find her hoard." We searched about the grape

trellis and over the

entire garden for ten minutes or more, but found no secret preserve of

apples. As we returned to the wood-shed,

Kate came out,

smiling disdainfully. "Found it?" she asked us, — a

question

which I felt to be an embarrassing one. With an air of triumph, she

then

displayed a fine yellow Sweet Harvey. "Oh, don't you think you are

cunning?"

muttered Tom. "But I'll find your hoard all the same." "Let me know when you do,"

replied Kate,

with a provoking laugh. "Oh, you'll know when I find

it," said Tom.

"I'll take what there is in it. That was all a blind — her going out to

the grape-vine," he remarked to me, as Kate turned away about her work.

"She went down there on purpose to fool us, and get us to hunt there

for

nothing." I went home quite fully informed

in regard to the

ethics of apple-hoards. The code was simple; it consisted in keeping

one's own

hoard undiscovered, and in finding and robbing those of others. "Have you got an apple-hoard?" I

asked

Addison, as soon as I reached home. For all reply, he winked his

left eye to me. "Doad's got one, too," he said,

after I had

had time to comprehend his stealth. "You didn't tell me," I remarked. Addison laughed. "That would be

great

strategy!" he observed, derisively, "to tell of it! But I only made

mine day before yesterday. I thought the early apples were beginning to

get

good enough to have a hoard. I want to get a big stock on hand for

September

town-meeting," he added. "I mean to carry a bushel or two, and peddle

them out for a cent apiece. The Old Squire put me up to that last year,

and I

made two dollars and ninety cents. That's better than nothing." "Are you really contented here?

Are you

homesick, ever?" I asked him. "Well," replied Ad, judicially,

after

weighing my question a little, "it isn't, of course, as it would have

been

with me if it had not been for the War, and father had lived. I should

be at

school now and getting ahead fast. But it is of no use to think of

that; father

and mother are both in their graves, and here I am, same as you and

Doad are.

We have got to make our way along somehow and get what education we

can. It is

of no use to be discontented. We are lucky to have so good a place to

go to. I

like here pretty well, for I like to be in the country better, on the

whole,

than in the city. Things are sort of good and solid here. The only

drawback is

that there isn't much chance to go to school; but after this year, I

hope to go

to the Academy, down at the village, ten or twelve weeks every season." "Then you mean to try to get an

education?"

I asked, for it looked to me to be a vast undertaking. "I do," replied Addison,

hopefully.

"Father meant for me to go to college, and I mean to go, even if I get

to

be twenty before I am fitted to enter. I will not grow up an ignoramus.

A man

without education is a nobody nowadays. But with a good education, a

man can do

almost anything." "Halse doesn't talk that way,"

said I. "I presume to say he doesn't,"

replied

Addison. "He and I do not think alike." "But Theodora says that she

means to go to

school and study a great deal, so as to do something which she has in

mind, one

of these days," I went on to say. "Do you know what it is?" "Cannot say that I do," Addison

replied,

rather indifferently, as I thought. "Oh, I suppose it is a good

thing for girls to

study and get educated," Addison continued. "But I do not think it

amounts to so much for them as it does for boys." This, indeed, was an opinion far

more common in 1866

than at the present time. "Perhaps it is to be a teacher?"

I

conjectured. "Maybe," said Addison. But I was thinking of

apple-hoards. There was a

delightful proprietary sense in the idea of owning one. It stimulated

some

latent propensity to secretiveness, as also the inclination to play the

freebooter in a small way. This was the first time that I

had ever had access to

an orchard of ripening fruit, and those "early trees" are well fixed

in my youthful recollections. Several of them stood immediately below

the

garden, along the upper side of the orchard. First there was the

"August

Pippin" tree, a great crotched tree, with a trunk as large round as a

barrel. Somehow such trees do not grow nowadays. The August Pippins began to

ripen early in August.

These apples were as large as a teacup, bright canary yellow in color,

mellow,

a trifle tart, and wonderfully fragrant. When the wind was right, I

could smell

those pippins over in the corn-field, fifty rods distant from the

orchard. I

even used to think that I could tell by the smell when an apple had

dropped off

from the tree! Then there were the "August

Sweets," which

grew on four grafts, set into an old "drying apple" tree. They were

pale yellow apples, larger even than the August Pippins, sweet, juicy

and

mellow. The old people called them "Pear Sweets." Next were the "Sour Harvey," the

"Sweet Harvey," and the "Mealy Sweet" trees. The

"Mealy Sweet" was not of much account; it was too dry, but the

Harveys were excellent. Some of the Sweet Harveys were almost as sweet

as

honey; at least, I thought so then. Then there were the "Noyes

Apple" and the

"Hobbs Apple." The Noyes was a deep-red, pleasant-sour apple, which

ripened in the latter part of August; the Hobbs was striped red and

green,

flattened in shape, but of a fine, spicy flavor. The "sops-in-wines," as, I

believe, the

fruit men term them, but which we called "wine-saps," were a

pleasant-flavored apple, scarcely sweet, yet hardly sour. A little

later came

the "Porters" and "Sweet Greenings," also the

"Nodheads" and the "Minute Apples," the

"Georgianas" and the "Gravensteins," and so on until the

winter apples, the principal product of the orchard, were reached. We began eating those early

apples by the first of

August, in spite of all the terrible stories of colic which Gram told,

in order

to dissuade us from making ourselves ill. As the Pippins and August

Sweets

began to get mellow and palatable, we rivalled each other in the haste

with

which we tumbled out of doors early in the morning, so as to capture,

each for

himself or herself, the apples which had dropped from the trees

overnight.

Every one of us soon had a private hoard in which to secrete those

apples which

we did not eat at the time. There were numerous contests in rapid

dressing and

in reckless racing down-stairs and out into the orchard. Little Wealthy, on account of

her youth, was, to some

degree, exempted from this ruthless looting. We all knew where her

hoard was, but

spared it for a long time. She believed that she had placed it in a

wonderfully

secret place, and because none of us seemed to discover it, she boasted

so much

that Ellen and I plundered it one morning, before she was awake, to

give her a

wholesome lesson in humility. A little later, just before the

breakfast hour,

Wealthy stole out to her preserve — to find it empty. I never saw a

child more

mortified. She felt so badly that she could scarcely eat breakfast, and

her lip

kept quivering. The others laughed at her, and soon she left the table,

and no

doubt shed tears in secret over her loss. After breakfast Ellen and I

sought her out, and

offered to give back the apples that we had taken. The child was too

proud,

however, to obtain them in such a way, and refused to touch one of them. No such clemency as had been

shown to Wealthy was

practised by any one toward the others; no quarter was given or taken

in the

matter of robbing hoards. For a month this looting went on, and was a

great

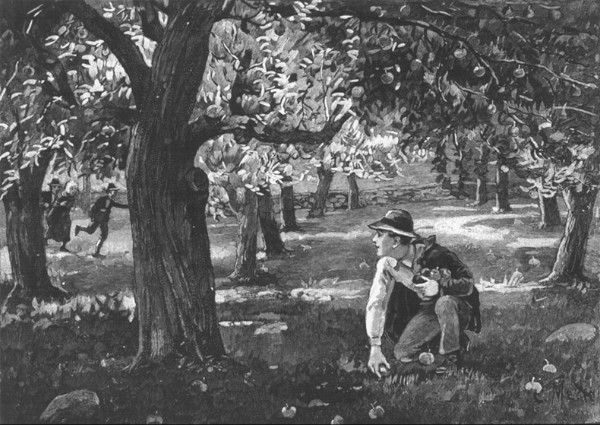

contest of wits.  THE EARLY APPLES. Theodora's was the only hoard

that escaped detection

during the entire summer and autumn. She had her apples hidden in an

empty

bee-hive, which stood out in the garden under the "bee-shed" about

midway in the row of thirteen hives. The most of us were a little

afraid of the

bees, but Theodora was one of those persons whom bees seem never to

sting. She

was accustomed to care for them, and thus to be about the hives a great

deal.

Not one of us happened to think of that empty bee-hive. The shed and

some lilac

shrubs concealed the place from the house; and Doad went unsuspected to

and

from the hive, which she kept filled with apples. We spent hours in

searching

for her hoard, but did not learn where she had concealed it until she

told us

herself, two years afterwards. Ellen had the worst fortune of

us all. We found her

hoard regularly every few days. At first she hid it in the wagon-house,

then up

garret, and afterward in the wood-shed; but no sooner would she

accumulate a

little stock of apples than some one of us, who had spied on her goings

and

comings, would rob her. Even Wealthy found Nell's hoard once, and

robbed it of

nearly a half-bushel of apples. Nell always bore her losses

good-denature, and

obtained satisfaction occasionally by plundering Halse and me. I remember that my first hoard

was placed in the very

high, thick "double" wall of the orchard. I loosened and removed a

stone from the orchard side of the wall, and then took out the small

inside

stones from behind it until I had made a cavity sufficient to hold

nearly a

bushel. Into this cavity I put my apples, and then fitted the outer

stone back

into its place, thus making the wall look as if it had not been

disturbed. This

device protected my apples for nearly a fortnight; but at length Ellen,

who was

on my track, observed me disappear suspiciously behind the wall one

day, and an

hour or two later took occasion to reconnoiter the place where I had

disappeared. She passed the hidden cavity

several times, and would

not have discovered it, if she had not happened to smell the mellow

August

Pippins of my hoard. Guided by the fragrance which they emitted, she

examined

the wall more closely, and finally found the loose stone. When I went

to my

preserve, after we had milked the cows that evening, I found only the

empty

hole in the wall. I next essayed to conceal my

hoard in the ground. In

the side of a knoll, screened from the house by the orchard wall and a

thick

nursery of little apple trees, I secretly dug a hole which I lined with

new

cedar shingles. For a lid to the orifice leading into it, I fitted a

sod. A

little wild gooseberry bush overhung the spot, and I fancied that I had

my

apples safely hidden. But never was self-confidence

worse misplaced! It was

a cloudy, wet afternoon in which I had thus employed myself. Halse had

gone

fishing; but Addison chanced to be up garret, reading over a pile of

old

magazines, as was his habit on wet days. From the attic window he

espied the

top of my straw hat bobbing up and down beyond the wall, and as he

read, he

marked my operations. With cool, calculating shrewdness he remained quiet for three or four days, till I had my new hoard well stocked with "Sweet Harveys," then made a descent upon it and cleared it out. Next morning, when, with great stealth and caution, I had stolen to the place, I found my miniature cavern empty except for a bit of paper, on which, with a lead-pencil, had been hastily inscribed the following tantalizing bit of doggerel: "He hid his hoard in the ground And thought it couldn't be found; But forgot, as indeed he should not, That the attic window overlooked the spot." For about three minutes I felt

very angry, then I

managed to summon a grin, along with a resolve to get even with Addison

— for I

recognized his handwriting — by plundering his hoard, if by any amount

of

searching it were possible to find it. Addison was supposed to have the

best

and biggest hoard of all, and thus far none of us had got even an

inkling as to

where it was hidden. I watched him as a cat might

watch a mouse for two

days, and made pretty sure that he did not go to his hoard in the

daytime. Then

I bethought myself that he always had a pocketful of apples every

morning, and

concluded that he must visit his preserve sometime "between days,"

most likely directly after he appeared to retire to his room at night. So on the following night I lay

awake and listened.

After about half an hour of silence, I heard the door of his room open

softly.

With equal softness I stole out, and followed Addison through the open

chamber

of the ell, down a flight of stairs into the wagon-house, and then down

another

flight into the carriage-house cellar. He had a lamp in his hand. When

he entered the cellar

the door closed after him, so that I did not dare go farther. I went

back into

the chamber, concealing myself, and waited to observe his return. He

soon made

his appearance, eating an apple; there was a smile on his face, and his

pockets

were protuberant. Next day I proceeded to search

the wagon-house

cellar, but for some time my search was in vain. There was in the cellar a large

box-stove, into which

I had often looked, but had seen only a mass of old brown paper and

corn-husks.

On this day I went to the stove and pulled out the rubbish, when lo! in

the

farther end I saw three salt boxes, all full of Pippins and August

Sweetings. I was not long in emptying those boxes, but I wanted to leave in the place of the apples a particularly exasperating bit of rhyme. I studied and rhymed all that forenoon, and at last, with much mental travail, I got out the following skit, which I left in the topmost box: "He was a cunning cove Who hid his hoard in the stove; And he was so awful bright That he went to it only by night. But there was still another fellow Whose head was not always on his pillow." I knew by the sickly grin on

Ad's face when we went

out to milk the cows next morning that my first effort at poetry had

nauseated

him; he could not hold his head up all day, to look me in the face,

without the

same, sheepish, sick look. Where to put my next hoard was a

question over which

I pondered long. I tried the hay-mow and several old sleighs set away

for the

summer, but Addison was now on my trail and speedily relieved me of my

savings. There were many obstacles to the

successful

concealment of apples. If I were to choose an unfrequented spot, the

others,

who were always on the lookout, would be sure to spy out my goings to

and fro.

It was necessary, I found, that the hoard should be placed where I

could visit

it as I went about my ordinary business, without exciting suspicion. We had often to go into the

granary after oats and

meal, and the place that I at last hit on was a large bin of oats. I

put my

apples in a bag, and buried them to a depth of over two feet in the

oats in one

corner of the bin. I knew that Addison and Halse would look among the

oats, but

I did not believe that they would dig deeply enough to find the apples,

and my

confidence was justified. It was a considerable task to

get at my hoard to put

apples into it, or to get them out; but the sense of exultation which I

felt,

as days and weeks passed and my hoard remained safe, amply repaid me. I

was

particularly pleased when I saw from the appearance of the oats that

they had

been repeatedly dug over. As I had to go to the granary

every night and morning

for corn, or oats, I had an opportunity to visit my store without

roundabout

journeys or suspicious trips, which my numerous and vigilant enemies

would have

been certain to note. The hay-mow was Halse's

hoarding-place throughout the

season, and although I was never but once able to find his preserve,

Addison

could always discover it whenever he deemed it worth while to make the

search. To ensure fair play with the

early apples, the Old

Squire had made a rule that none of us should shake the trees, or knock

off

apples with poles or clubs. So we all had equal chances to secure those

apples

which fell off, and the prospect of finding them beneath the trees was

a great

premium on early rising in the months of August and September. I will go on in advance of my

story proper to relate

a queer incident which happened in connection with those early apples

and our

rivalry to get them, the following year. The August Sweeting tree stood

apart

from the other trees, near the wall between the orchard and the field,

so that

fully half of the apples that dropped from it fell into the field

instead of

into the orchard. We began to notice early in

August that no apples

seemed to drop off in the night on the field side of the wall. For a long time every one of us

supposed that some of

the others had got out ahead of the rest and picked them up. But one

morning

Addison mentioned the circumstance at the breakfast table, as being

rather

singular; and when we came to compare notes, it transpired that none of

us had

been getting any apples, mornings, on the field side of the wall. "Somebody's hooking those

apples, then!"

exclaimed Addison. "Now who can it be?" For we all knew that a good

many apples must fall into the field. "I'll bet it's Alf Batchelder!"

Halse

exclaimed. But it did not seem likely that Alfred would come a mile, in

the

night, to "hook" a few August Sweets, when he had plenty of apples at

home. Nor could we think of any one

among our young

neighbors who would be likely to come constantly to take the apples,

although

any one of them in passing might help himself, for fall apples were

regarded

much as common property in our neighborhood. Yet every morning, while there

would be a peck or

more of Sweetings on the orchard side of the wall, scarcely an apple

would be

found in the field. Addison confessed that he could

not understand the

matter; Theodora also thought it a very mysterious thing. The oddity of

the

circumstance seemed to make a great impression on her mind. At last she

declared that she was determined to know what became of those Sweets,

and asked

me to sit up with her one night and watch, as she thought it would be

too dark

and lonesome an undertaking to watch alone. I agreed to get up at two

o'clock on the following

morning, if she would call me, for we wisely concluded that the

pilferer came

early in the morning, rather than early in the night, else many apples

would

have fallen off into the field after his visit, and have been found by

us in

our early visits. I did not half believe that

Theodora would wake in

time to carry out our plan, but at half-past two she knocked softly at

the door

of my room. I hastily dressed, and each of us put on an old Army

over-coat, for

the morning was foggy and chilly. It was still very dark. We went out

into the

garden, felt our way along to a point near the August Sweeting tree,

and sat

down on two old squash-bug boxes under the trellis of a Concord

grape-vine,

which made a thick shelter and a complete hiding-place. For a mortal long while we sat

there and watched and

listened in silence, not wishing to talk, lest the rogue whom we were

trying to

surprise should overhear us. At intervals Theodora gave me a pinch, to

make

sure that I was not asleep. An hour passed, but it was still dark when

suddenly

we heard, on the other side of the wall, a slight noise resembling the

sound of

footsteps. Instantly Doad shook my arm.

"Sh!" she

breathed. "Some one's come! Creep along and peep over." I stole to the wall, and then,

rising, slowly parted

the vine leaves, and tried to see what it was there. Presently I

discerned one,

then another dim object on the ground beyond the wall. They were

creeping

about, and I could plainly hear them munch the apples. Then Theodora peeped. "It's two

little bears, I

believe," she breathed in my ear, with her lightest whisper, yet in

considerable excitement. "What shall we do?" I peeped again. If bears, they

were very little ones. I mustered my courage. As a

weapon I had brought an

old pitchfork handle. Scrambling suddenly over the wall, I uttered a

shout, and

the dark objects scudded away across the field, making a great scurry

over the

stubble of the wheat-field, but they were not very fleet. I came up

with one of

them after a hundred yards' chase, when it suddenly turned and faced me

with a

strange loud squeak! Drawing back, I belabored it with my fork handle

until the

creature lay helpless, quite dead, in fact. Theodora came after me in alarm.

"Oh, my, you

have killed it!" she exclaimed. "What can it be?" I put my hand cautiously down

upon its hair, which

was coarser than bristles and sharp-pointed. Turning the body over with

the

fork handle, I found that it was really heavy. We could not, in the darkness,

even guess what the

animal was, and went back to the house much mystified. The Old Squire

had just

arisen, and we told him the story of our early vigil. "Wood-chucks, I

guess," was his comment, but we knew that they were not wood-chucks.

Addison

was then called up, to get his opinion, and when told of the animal's

exceedingly coarse, sharp-pointed hair, he exclaimed, "I know what it

is!

It's a hedgehog!" He bustled around, got on his

boots, and went out

into the field with me. It was now light, and he had no sooner bent

down over

it than he pronounced it to be a hedgehog fast enough, or rather a

Canada

porcupine. Its weight was over thirty pounds, and some of the quills on

its

back were four or five inches in length, with needle-like, finely

barbed

points. The other hedgehog escaped to

the woods, and did not

again trouble us. The next summer the August Sweetings that fell into

the field

from the same tree were quite as mysteriously taken at night by a

cosset sheep,

which for more than a fortnight escaped nightly from the farm-yard, and

returned thither of its own accord after it had stolen the apples.

Again

Theodora and I watched for the pilferer, and captured the cunning

creature in

the act. During that first year at the

farm, the old folks did

not pay much attention to our apple-hoards, but by the time our

contests were

under way the second season, they, too, caught the contagion of it,

from

hearing us talk so much about it at the breakfast table. At first the

Old

Squire merely dropped some remarks to the effect that, when he was a

boy, he

could have hidden a hoard where nobody could find it. "Well, sir, we would like to see

you do

it!" cried Halse. The old gentleman did not say at

the time that he

would, or would not, attempt such an exploit. Moved by Ellen's

serio-comic

lamentations over her losses, Gram also insinuated that she knew of

places in

the house in which she could make a hoard that would be hard for us to

find;

but the girls declared that they would like to see her try to hide a

hoard away

from them. Not many days after these

conversations had occurred,

the Old Squire rather ostentatiously took a very fine August Pippin

from his

pocket, as we were gathering round the breakfast table, and, after

thumbing it

approvingly, set it beside his plate, remarking, incidentally, that if

one

wanted his apples to ripen well, and have just the right flavor, it was

necessary that he should place his hoard in some dry, clean, perfectly

sweet

place. Of course we were not long in

taking so broad a hint as

that. Several sly nudges and winks went around the table. "He's got one!" Addison

whispered to me, as

Gram poured the coffee, and from that time the Old Squire, in all his

goings

and comings, was a marked man. He had thrown down a challenge to us,

and we

were determined to prove that we were as smart as he had been in his

youthful

days. But for more than a week we were unable to gain the slightest

hint as to

where his preserve was situated. Meantime Gram had also begun to place

a nice

August Sweet beside her own plate every morning, as she glanced with a

twinkle

in her eye over to the Old Squire. We rummaged everywhere that

week, and even forgot to

carry on mutual injury and reprisal, in our desire to humble the pride

of our

elders. We even bethought ourselves of the words "perfectly sweet,"

which the old gentleman had used in connection with hoards, and looked

in the

sugar barrel, but quite in vain. Yet all the while we were daily going

by the

place where the Old Squire's hoard was concealed; passing so near it

that we

might have laid hands on it without stepping out of our way, for it was

in the

wood-house beside the walk which led past the tiered up stove wood into

the

wagon-house and stable. Ten or twelve cords of wood,

sawed short and split,

had been piled loosely into the back part of the wood-house, but in

front of

this loose pile, and next the plank walk, the wood had been tiered up

evenly

and closely to a height of ten feet. The Old Squire managed to pull

from this

tier, at a height of about four feet, a good-sized block, and then,

reaching in

behind it, had made a considerable cavity. Here he deposited his

apples,

replacing the block, which fitted to its place in the tier so well that

the

woodpile appeared as if it had not been disturbed. Shrewdly mindful of

the fact

that our keen nostrils might smell out his preserve, he cunningly set

an old

pan with a few refuse pippins in it on a bench close beside the place. Gram's hoard was hidden, with

equal cunning, in the

"yarn cupboard," where were kept the woollen balls and yarn hanks,

used in darning and knitting, — a small, high cupboard, with a little

panel

door, set in the wall of the sitting-room next to the fireplace and

chimney.

The bottom of this cupboard was formed of one broad piece of pine

board, which

seemed to be nailed down hard and fast; but the old lady, who knew that

this

board was loose, had raised it and kept her apples in a yarn-ball

basket

beneath it. She often had occasion to go to

the cupboard to get

or replace her knitting, and for a long time none of the girls

suspected her

hiding-place. The plain fact was that those girls, as a rule, steered

clear of

the yarn cupboard, for they none of them very much liked to knit or

darn. But

at last Ellen happened to go to it one day for a darning-needle, and

smelled

the apples. Even then she could not discover the hoard, but she went in

search

of Theodora, who penetrated the secret of the loose bottom board. They came with great glee to

tell us of their

discovery, and we were thereby stimulated to renewed efforts to unearth

the Old

Squire's preserve. The girls promised to say nothing of their discovery

for a

day or two, and at Ellen's suggestion we agreed that if we could find

Gramp's

hoard, we would rob both hoarding-places at once and have the laugh on

them

both at the same time. We had watched the Old Squire

closely, and felt sure

that he did not go to his hoard at any time during the day. As he was

an early

riser, it seemed probable to us that he did his apple-hoarding before

we were

astir. Addison and I accordingly agreed to get up at three o'clock the

following morning and secretly watch all his movements. By a great

effort we

rose long before light, and dressing, stole out through the wood-house

chamber

and down the wagon-house stairs into the stable. Here I concealed

myself behind

an old sleigh, while Addison went back into the wood-house and posted

himself

on the high tier of wood that fronted on the passageway, lying there in

such a

posture that he could get a peep of the long walk. It had hardly begun to grow

light, when we heard the

old gentleman astir in the kitchen. Presently he came out through the

stable

and fed the horses, then returned. As he went back through the

wood-house, he

stopped on the walk beside the high tier of wood on which Addison lay.

After

listening and looking about him, he removed the block of wood, took out

a fine

pippin from his hoard, and carefully replaced the block. This amused Ad so greatly that

he nearly shook the

tier of wood down in his efforts to repress laughter, and after the old

gentleman had gone into the house, he came tiptoeing out into the

stable to

tell me, with much elation, what he had seen. During the forenoon we examined

the hoard and told

the girls about it. We arranged to rob both the old folks' hoards late

that

evening, and fill our own with the plunder. To emphasize the exploit,

we agreed

to take some of the largest apples to the breakfast-table next morning.

We

fancied that when the old folks saw those apples, and found out where

we got

them, they would think there were young people living nearly as bright

as those

of fifty years ago. Theodora did not really promise

that she would assist

in the scheme, but she laughed a good deal over it, and seemed to

concur with

the rest of us. That evening as soon as the old

folks had retired and

the house had become quiet, Addison and I cleared out the Old Squire's

preserve; and, meantime, Ellen and Theodora had slipped down-stairs

into the

sitting-room and emptied Gram's hoard in the yarn cupboard. We met out

in the

garden and divided the spoils; then not liking to trust each other to

go

directly to our respective hoards, we deposited our shares of the

plunder in

three different boxes in the wagon-house, and looked forward with no

little

zest to the fun next morning at the breakfast-table. But on visiting the boxes next

morning, they were all

empty! Some one had made a clean sweep. Not an apple was left in them!

Addison

and I were astounded when we compared notes a few minutes before

breakfast.

"Who on earth could have done it?" he whispered, after he found out

that I was not the traitor. We hurried to the wood-house and

peeped into the Old

Squire's hoarding-place. It was brimful of apples! A light began to

dawn upon

us. Had the old gentleman watched our performance on the previous

evening and

outwitted us all? It looked so, for on going in to breakfast, there

beside the

plates of each of the old folks stood a great nappy dish, heaped full

of choice

Pippins and Sweets! Addison stole a look around and then dropped his

eyes; I

did the same, while Ellen looked equally amazed and disconcerted.

Theodora,

too, remained very quiet. We concluded that our elders had

completely outdone

us, and that they were enjoying their victory in a manner intended to

convey

their ironical appreciation of our small effort to rob them. The more

we

considered the matter, the more sheepish we felt. "These are charming good

pippins, aren't they,

Ruth?" said the old gentleman to Gram. "Charming," answered she. Addison gave me a punch under

the table, as if to

say, "Now they are giving us the laugh." "And I'm sure we're much obliged

for them,"

the Old Squire continued. "Indeed, we are obliged," said

Gram. Their remarks seemed to me a

little odd, but I didn't

look up. Not another word was spoken at

the table, but

afterwards Addison and Ellen and I got together in the garden and

mutually

agreed that we had been badly beaten at our own game. "They are too old and

long-headed for us to

meddle with," said Addison. "I cannot even imagine how they did it. I

guess we had better let their hoards alone in the future." None the

less

we could not help thinking that there had been something a little queer

about

our defeat. It was nearly two years later

before the truth about

that night's frolic came to light. Theodora did it. She could not bear

to have

the old folks beaten and humiliated by us, for whom they were doing so

much.

After we had robbed their hoarding-places, she sallied forth again and

took all

of our shares as well as her own, and then having replenished the

looted

hoarding-places, she filled the two nappy dishes from her own hoard and

set

them beside their plates. The best part of the joke was

that the Old Squire and

Gram never knew that they had been robbed, and thought only that we had

made

them a present of some excellent apples. When Theodora saw how

chagrined the

rest of us were, she kept the whole matter a secret. |