|

1999-2004 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click Here to return to |

|

1999-2004 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click Here to return to |

FINISHING THE NEST

THE first wasp that emerges from a nest is not a

queen.

THE first wasp that emerges from a nest is not a

queen.

It is smaller than the queen-mother, is not so brightly coloured, and is called a “worker.” It is an imperfect female, unable, as a rule, to lay eggs. The first thing it wants is something to eat, and this the queen-mother gives it.

It very often hides away in an empty cell for a while, as though to rest, or “think it over.” When it goes into a cell it now does so head first, with only its tail protruding.

The time for development from egg to imago, or perfect insect, seems to vary, perhaps according to the species, perhaps according to the temperature. One observer reports his wasps as five days in the egg, nine in the larval state, and thirteen in the pupal state, - twenty-seven days in all. Another, his as eight days in the egg, twelve or fourteen in the larval state, ten in the pupal, - thirty-one or thirty-two days in all. As a rule, it probably takes about a month to complete the development. All of the wasps hatched early in the season are workers, and as soon as they come out of their cells they prove their right to the name, for they take upon themselves the whole work of the nest. The queen can now devote her time to egg-laying, for the young workers clean out the cells and make them ready to receive another set of eggs. They also enlarge the comb by building more cells. They fly to a weather-beaten rail-fence or to an old stump, and there they stand and gnaw lengthwise of the grain until they have a little ball of wood-fibre, with which they fly home. They chew it thoroughly, wetting it with their sticky saliva, and then proceed to shape it into more cells.

Nobody tells them how to do all this, but they remember, somehow, that their mother did it this way before they were born.

Young Vespa lays down pulp for a roof, then builds the cell walls by adding strips of pulp at the edges and biting them into shape.

As she stands on the rim of an unfinished cell, adding pulp, the walls rise slowly, and soon a little six-sided cell testifies to her skill as a comb builder.

One sometimes has a chance to see the yellow-jackets at work on a nest that has been destroyed -- or where an attempt has been made to destroy it. If any of the little occupants escape destruction they will return to the old place and start the nest again, building it up, or rather down, from the foundation if necessary.

One should be on hand as soon as the agitation following the removal of the nest subsides enough to make a near approach safe, or else the first cells will have been built, and the whole enclosed in an envelope that completely conceals what is going on inside.

As soon as the workers of an undisturbed nest

begin to come out, they go to work upon the walls of the nest, adding layer

after layer, until sometimes there are a dozen or more.

As soon as the workers of an undisturbed nest

begin to come out, they go to work upon the walls of the nest, adding layer

after layer, until sometimes there are a dozen or more.

Quickly the little nest made by the mother wasp increases in size, when all is well with the swarm.

But there seem to be a great many vicissitudes in the lives of the hornets and yellow-jackets, and one may often find in an out-building a dozen of their little round nests, begun but never finished.

Doubtless something happened to the queen before her first brood was hatched. A greedy bird may have swallowed her, a boy may have killed her, she may have fallen into the water and been drowned, or there may have come a cold, rainy spell to which she succumbed, for wasps are delicate creatures and perish in large numbers during a bad season. Indeed, they are more dependent upon fair weather for their success in life than are many less hardy-looking animals.

Even where the brood has begun to hatch, if the queen is lost the workers soon abandon the nest.

Wasps can often be watched at work on the outer covering of the nest.

To pursue this particular line of observation, it is well to select a cold and cloudy day, as the wasps are then not so easily excited.

Dr. Ormerod, who spent a great deal of time studying wasps, has well described the method of nest-building as follows:

“When a wasp came home laden with building materials, she did not immediately apply these, but flew into the nest for about half a minute, for what purpose I could not ascertain. Then emerging she promptly set to work. Mounting astride on the edge of one of the covering sheets, she pressed her pellet firmly down with her fore-legs till it adhered to the edge, and walking backwards, continued this same process of pressing and kneading till the pellet was used up, and her track was marked by a short dark cord lying along the thin edge to which she fastened it. Then she ran forwards, and, as she returned again backwards, over the same ground, she drew the cord through her mandibles, repeating this process two or three times till it was flattened out into a little strip or ribbon of paper, which only needed drying to be indistinguishable from the rest of the sheet to which it had been attached.”

Dr. Ormerod also discovered that each wasp has not a place of her own at which to work, but that all work anywhere and anyhow, as bees build their combs. They know what the final result is to be, and all work towards that without finishing individual parts as they go along.

The variegated appearance of many nests is doubtless due to the fact that different wasps bring in materials of different colours and apply them indiscriminately.

Dr. Ormerod is of the opinion that only young wasps build, and this seems probable, as the secretion necessary to form the paper would be most abundant in young insects, just as with bees the younger ones perform the office of nurses, and supply the food partly digested by themselves to the larvae.

Young wasps are larger than old ones, and their

wings are not tattered, and it was such only that Dr. Ormerod saw at work on the

nest.

Young wasps are larger than old ones, and their

wings are not tattered, and it was such only that Dr. Ormerod saw at work on the

nest.

The old wasps find work enough in providing insects for the many hungry larvae. A flourishing wasp's-nest is a scene of constant building up and tearing down.

No sooner is the outer covering completed than the combs have to be enlarged and new tiers of them added.

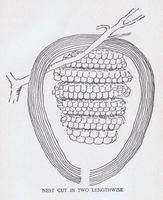

This enlarging is done by gnawing away the walls from the inside, and adding layers on the outside. Thus the space within is increased without exposing the combs.

There is never any connection between the walls of the cells and the combs.

The combs are suspended from supports above, and hang free in the space formed by the enclosing walls.

When a comb has reached a certain size the wasps do not continue to enlarge it, but suspend another comb below it, fastening the new structure to the old by a stout paper-pillar support in the centre, and this is often reinforced by a number of side supports.

The wasps use the roof of the new comb as a floor to the space above, and indeed a wasp's-nest is but a series of floors, or stages, suspended one below another, each floor having attached to its under side a large number of cells opening mouth down.

The same cells are generally used two or three times, for as soon as one brood is hatched the cells are cleaned and put in repair by the workers and more eggs are laid in them by the queen.

The first cells built are smaller than those in the later combs. As the colony prospers, it becomes generous in its treatment of the new members. The cells built by the many industrious workers are larger, and their well-fed occupants are also larger; indeed towards the end of the season there sometimes come forth large and portly workers that approximate the queen in size.