|

1999-2004 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click Here to return to |

|

1999-2004 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click Here to return to |

STARTING THE NEST

THE well-known grey structures wasps build in

trees, under the eaves or in the ground, are generally seen in the fall of the

year. Then the leaves have left the tree branches bare disclosing the nests so

carefully hidden under the foliage in the summer time.

THE well-known grey structures wasps build in

trees, under the eaves or in the ground, are generally seen in the fall of the

year. Then the leaves have left the tree branches bare disclosing the nests so

carefully hidden under the foliage in the summer time.

Moreover, in the fall of the year, boys fearlessly take down these nests and hang them up as ornaments in the house.

Boys do not take them down in the summer-for a very good reason; but they know that after the first frost the nest has no fiery occupants to defend it; it is an abandoned domicile-safe booty for whoever finds it.

Sometimes a hornet's nest is nearly as large as a bushel basket, but that is at the end of the season. The beginning of every nest is simple enough, and consists of but a cluster of three small cells.

Early in the summer the females of the social wasp may be seen flying about, searching everywhere for a good building-site.

One is suspicious that Madam Vespa uses this nest-hunting as excuse for a prolonged lark, seizing the opportunity to investigate her little universe, and find out a great many things besides the best location for a home. The large yellow queens of the yellow-jackets, may be seen flying about in the spring, peering into every cranny in the woods, investigating every fallen log and heap of rubbish, poising on vibrating wings under the eaves of buildings, examining every growing tree, bush, or herb, and what is more noticeable, examining with equal minuteness any human brother who happens to be abroad. Certainly they do not intend to suspend a nest from any part of your person, yet they favor you with as prolonged and careful an examination as they give to any tree, or rock, or roof.

If the windows are open they are sure to come into the house; then they are in a state of consuming curiosity. What does everything mean? They examine each article of furniture in a comically thorough manner, flying around and behind it, and hanging buzzing so close to it that they seem to be testing its quality with their antennae. Sometimes it is but one or two objects that thus occupy them, sometimes one of them will remain an hour in a room satisfying herself concerning every object in it, not slighting any quiet and inoffensive occupant that may be there. Indeed the human owner of this strange nest seems oftentimes to puzzle her more than all else, and if one but keeps still she proceeds upon a very flattering inspection, -- very likely poising directly in front of one's eyes, so close that the breeze made by her little wings can be distinctly felt. Her small face is close to yours, her large eyes gazing intently into your own; and there she hangs while you, flattered by her close attention, sit and look calmly back at her or close your eyes until the close buzzing of her ladyship ceases to roar in your ears. One living in a region of wasps becomes quite familiar with these spring visits, and at least one person feels slighted if Queen Vespa enters the room and goes out without noticing its human occupant. It is unnecessary to say that wasps under such circumstances never sting. They are simply about their business, trying to get an education out of the only book at their command. In a few weeks these large yellow queens disappear. Other, smaller, less prodigally yellow creatures roam the fields, but the large queens are absorbed in domestic duties that keep them within their doors.

The queen-hornets also intrude their black-and-white presence in people's houses in the spring, but they do not seem so curious nor so friendly. Their investigations seem rather aimless, in comparison with those of their yellow relative, and their manner is much more suspicious and, if one may say so, tempestuous.

Only the perfect females or “queens” of the Vespae survive the winter, and when they are wakened to life by the warm sun of early summer, each little queen wasp has upon her shoulders the responsibility of the whole family, -- she must build her own house as well as take care of her own offspring. She does not start in life, like the queen bee, with thousands of helpers ready to do all the work and even to feed her royal highness.

She must do everything for herself, at least at first.

When she has found a place to her mind, perhaps

in the branches of a tree, or under the projecting eaves of a building, or in a

hole in the ground, Vespa betakes herself to a grey and weatherworn rail, or to

an old stump, and there she sits and gnaws lengthwise of the grain until she has

a little bundle of wood-fibre in her jaws.

When she has found a place to her mind, perhaps

in the branches of a tree, or under the projecting eaves of a building, or in a

hole in the ground, Vespa betakes herself to a grey and weatherworn rail, or to

an old stump, and there she sits and gnaws lengthwise of the grain until she has

a little bundle of wood-fibre in her jaws.

This she takes to her chosen site and chews into pulp, mixing it with saliva from her mouth.

Now behold the first paper-maker of the world at work!

For the social wasps were making a serviceable paper ages and ages before man dreamed of such a thing.

When the Egyptians were laboriously cutting their records in stone, or drawing them up on the pressed pith of the papyrus, and the Europeans theirs on the inner bark of trees, and the North American Indians were tanning the hides of animals and painting their messages upon them, the wasp folk were busy making a true paper, a paper that man finally learned to make, in essentially the same way that the wasp makes it.

For paper is only vegetable fibre reduced to pulp and pressed into sheets.

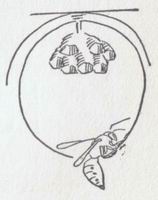

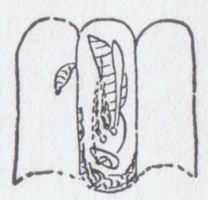

Having gathered her little ball of wood-fibre, and reduced it to a pulp of proper consistency by chewing and moistening with sticky saliva, Vespa first builds a slender stem or support for her future home.

To the end of this she hangs a little cluster of three or more hexagonal cells, also of paper.

She begins at the roof and builds down, suspending her habitation from above, A instead of building it on foundations that rest on the earth.

She begins her first cell, but does not finish

it before she starts another, and when she has a cluster of three half-finished

cells she lays an egg in the first one, and goes on building. As fast as the

cells are large enough she deposits an oblong white egg in each, placing it in

an angle of the cell and about one half or two thirds down, or what will be one

half or two thirds down when the cell is finished.

She begins her first cell, but does not finish

it before she starts another, and when she has a cluster of three half-finished

cells she lays an egg in the first one, and goes on building. As fast as the

cells are large enough she deposits an oblong white egg in each, placing it in

an angle of the cell and about one half or two thirds down, or what will be one

half or two thirds down when the cell is finished.

Her cells are six-sided, and are like honey-comb cells, excepting that they are made of paper instead of wax, and are suspended mouth down instead of lying on one side.

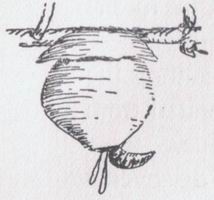

Since the cells hang mouth down, one naturally wonders why the eggs do not fall out as soon as put in.

The reason is that each is covered with a sticky substance, so that it is glued firmly to the cell wall.

The ancients had as little idea of the origin of wasps as they had of the origin of bees, and while they believed the bees were bred from the decaying carcass of a bull, the wasps, they tell us, came from the dead body of an ass or a horse, the fierce swift hornets owing their origin to the body of a war-horse.

There was also a superstition among the Egyptians that wasps were generated from the decaying carcass of a crocodile.

However, a later generation discovered that wasps proceed from eggs laid in the cells of the nest by the queen wasp.

The egg is generally placed in an inner angle of the cell, and is attached by one end.

Her first three cells completed, Vespa starts another row of cells around them, depositing an egg in each as soon as it is ready.

She evidently does not consider these exposed

cells a safe resting-place for her progeny, for no sooner has she formed a

little group of nine or a dozen cells than she proceeds to make a paper wall

about them.

She evidently does not consider these exposed

cells a safe resting-place for her progeny, for no sooner has she formed a

little group of nine or a dozen cells than she proceeds to make a paper wall

about them.

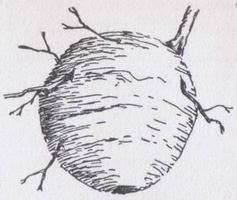

The result of her labours is a pretty little grey ball, with a hole in the bottom, enclosing the group of cells, but not attached to them. The first wall made consists of but one layer of grey paper, and at that stage the nest looks its prettiest.

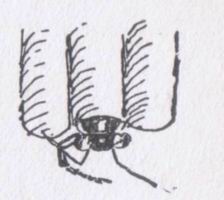

Vespa finally devotes all her time to caring for her progeny, for in a few days the first eggs laid have hatched into tiny white maggot-like larvae, and every day more eggs hatch out. Queen Vespa is obliged to go hunting food for these ravenous infants. They are still attached to the side of the cell by the tail end, but their mouths are free, and are always ready to open for something to be put in.

They have little round white heads, with little pin points of eyes and a pair of tiny, brown, horny jaws. The eyes of the larva are simple, the compound eyes not appearing until the adult form. When the comb is jarred, out are thrust all these little heads, and the mouths are opened wide, for they suppose that Mother Vespa is coming to feed them.

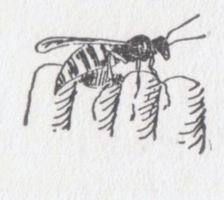

When a number of the eggs have hatched, Vespa

devotes most of her time to catching flies and other insects, chewing them up

and feeding the hungry youngsters in the cells with them.

When a number of the eggs have hatched, Vespa

devotes most of her time to catching flies and other insects, chewing them up

and feeding the hungry youngsters in the cells with them.

One is reminded of a mother bird feeding her nestlings, when watching the mother wasp going from cell to cell, and putting food into each little open mouth.

The larvae are always ready to open their mouths, and it is no wonder they are forever asking for more, as they grow at a marvellous rate, in the course of a few days filling their cradle cells with their plump, white bodies.

One trying ordeal every young Vespa has to pass through, and that is the change of position in its downward-opening cell. Since the egg is glued to an angle of the cell part way down, when it hatches, the larva grasps the cell with two little feet at the end of its tail, at the same spot where it was hatched. As it grows larger, however, it must manage somehow to reach the bottom of the cell, so that it may have room to continue its growth.

This migration to the bottom of the cell

necessitates turning around twice, letting go its hold on the side of the cell,

and yet keeping its position in the downward-pointing cell so as not to fall

out.

This migration to the bottom of the cell

necessitates turning around twice, letting go its hold on the side of the cell,

and yet keeping its position in the downward-pointing cell so as not to fall

out.

If the difficult feat of letting go, turning around, and moving to the bottom of the cell is accomplished, all is well.

But sometimes it is not accomplished. Poor baby Vespa, using her still useful tail-feet and her jaws to hang on by, slips or makes a miscalculation, and out it tumbles head over heels.

It is said the mother wasp sometimes puts it back after such an accident but generally it lies and wriggles in the cold outer world until death claims it.

Or if it falls out later in the season the worker wasps carry it out of the nest and leave it to perish.

But if it once gets fixed in the bottom of the

cell, with its head hanging down, all it has to do is to stay there.

But if it once gets fixed in the bottom of the

cell, with its head hanging down, all it has to do is to stay there.

This may look difficult, but it is really easy, for young Vespa is now a fat, white grub, or larva, with a brown head, footless, it is true, but with a way of ruffling up the sides of its body that enables it to fit tightly in the cell and there remain.

When the larva has reached the limit of its growth it finds its mouth full of silk. This comes out through a hole in its lip, and whenever it touches anything with its mouth little viscid threads like saliva are drawn out, and these harden into a fine, glistening silk.

Now young Vespa ceases to crave food. She touches the side of her cell with her mouth, draws back her head, touches another part of her cell, draws back her head, -- each time pulling out sticky threads that harden into silk.

Thus moving her head about, she lines all but

the bottom of her cell with soft, tough, white silk; then she reaches out her

head and weaves back and forth, back and forth, over the opening to her cell,

until she has formed a strong cap or roof over her head. From the very beginning

she has more responsibility than the young bee; no fond nurse seals the opening

to her cell, she is obliged to do that wholly for herself. The cap made, the

infant is now lying in a silken bag of her own manufacture, open at one end and

closed at the other with a cap of silk that is heavier than the silk used in

making the rest of the bag.

Thus moving her head about, she lines all but

the bottom of her cell with soft, tough, white silk; then she reaches out her

head and weaves back and forth, back and forth, over the opening to her cell,

until she has formed a strong cap or roof over her head. From the very beginning

she has more responsibility than the young bee; no fond nurse seals the opening

to her cell, she is obliged to do that wholly for herself. The cap made, the

infant is now lying in a silken bag of her own manufacture, open at one end and

closed at the other with a cap of silk that is heavier than the silk used in

making the rest of the bag.

Her cocoon, if such it can be called, is much heavier and stronger than the similar covering the young bee makes for itself.

She is now safely wrapped up, her silk covering preventing the too rapid evaporation of the juices of her body.

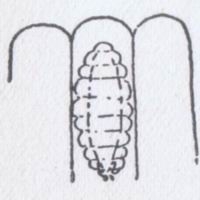

Lying there motionless, a marvellous change comes over her. She loses her fat larval form, a waist line appears, below it is a ringed abdomen, above it is a thorax with incipient legs and wings, and a waspish-looking head.

She is now a “pupa,” and at one stage of her

transformation is a very charming little creature, as she is as white as snow,

and has the daintiest legs and antennae lying close to her body.

She is now a “pupa,” and at one stage of her

transformation is a very charming little creature, as she is as white as snow,

and has the daintiest legs and antennae lying close to her body.

As time goes on, however, she grows darker-coloured until finally a perfect wasp lies in the silk-lined cell.

During her larval life Vespa sheds her skin as she increases in size, and finally, throwing off the last delicate covering from her pupal body, she is ready to step forth into the world and see what is going on there.

She reaches out her jaws, which are much larger

and stronger than the brown dots of jaws she possessed as a larva, and with them

cuts a hole in the cap she spun over her head a few days ago. As she works she

moistens the spot with saliva.

Snip, snip, snip, go the jaws in the dark cell.

One can easily hear them at work. Then a little opening appears. Snip, snip, snip, go the jaws until the hole is large enough to let out one of the antennae.

This organ, newly freed from confinement, waves about as though examining the world into which its little owner is about to enter.

But the jaws are still snipping, and finally the cap is so nearly cut away that Vespa's face can be seen filling the opening of the cell.

Then a foot appears, a fore-leg is stretched out, and very likely the first thing it does is to clean the antenna.

It is very amusing to watch a young Vespa coming

out of its cell, tucked away, all but the head and fore-legs, and industriously

cleaning its face and hands and polishing up its antennae.

It is very amusing to watch a young Vespa coming

out of its cell, tucked away, all but the head and fore-legs, and industriously

cleaning its face and hands and polishing up its antennae.

It takes its time, and when it has rested from the effort of uncapping its cell, and has thoroughly made the toilet of its head and hands, it begins to pull itself out.

It grasps the surrounding comb with its fore-feet, and struggles until it has pulled out its second pair of legs.

The remainder is easy, and in a moment more a shining young wasp stands on the comb and surveys its surroundings.