|

1999-2004 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click Here to return to |

|

1999-2004 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click Here to return to |

LEGS AND WINGS

SIX is the allotted number of legs in the insect world, and this number has Vespa. They, with her wings, are borne by the compact thorax, whose value in insectdom is principally for affording points of attachment to the organs of progression, and a place of support for the muscles that move those organs.

Like the bees, the wasps are eternally making their toilet.

Vespa, like a neat old tabby-cat, washes her face and hands with her tongue. She puts her paws, so to speak, in her mouth and licks them clean, then while they are presumably still damp, she draws them over her head, turning that important part of her diminutive person this side and that, very much as puss does when performing the same office.

Vespa cleans her wings, thorax, and abdomen with

her legs, like a bee, but she is not so particular about her hinder parts as is

my lady the bee. It is not necessary, as she is a hard and polished person,

encumbered with but few hairs, and those not of a dust-catching structure.

Vespa cleans her wings, thorax, and abdomen with

her legs, like a bee, but she is not so particular about her hinder parts as is

my lady the bee. It is not necessary, as she is a hard and polished person,

encumbered with but few hairs, and those not of a dust-catching structure.

Her precious antennae receive a great deal of attention, and, like the bee, she has implements on purpose to clean them.

Her antenna cleaners, though not so well-finished as those of the bee, resemble them in structure.

In the bend of the fourth and fifth joints of each foreleg is the cleaner.

It consists of a little flattened prong or valve hanging from near the lower end of the fourth joint and of a curved groove at the upper end of the fifth joint.

This groove is fitted with a circle of teeth.

When the antenna is to be cleaned, the leg is raised above it, the antenna is

slipped along until it rests in the groove, then the leg is flexed, the valve or

prong fits down over the antenna, and as the latter is pulled through, the edges

of the valve on one side, and the teeth of the groove on the other, clean it

perfectly.

Vespa is particularly fond of exercising these clever little arrangements for keeping the antennae in order, and whenever she is at rest may be seen giving frequent dabs at her face, first one side and then the other, each time drawing an antenna through its cleaner. She seems to do it unconsciously while she sits meditating, as some people pull their moustaches or twist their hair. Occasionally she makes a careful and prolonged toilet, scraping and pulling her antennae many times in succession.

Besides these admirable instruments for toilet purposes, there is a pair of sharp prongs on the lower end of the fifth joint of Vespa's middle and hind legs, and these are used in cleaning the legs and wings. The wasp is very, skilful with them, evidently understanding perfectly their value as articles of the toilet.

Otherwise Vespa's legs are not remarkable. She does not use them for pollen gathering, and so lacks the pollen-collecting implements of the bee, and she does not use them to any great extent in nest-building, -- that important and interesting work being performed principally by her jaws and tongue.

Vespa goes whizzing through the world propelled

by wings that in themselves do not appear capable of sustaining her weight in

the air. Nor were they capable but for the powerful motor that impels them with

such force and skill that they are apparently able to defy the attraction of

gravitation, and spurning the earth bear her aloft in the air.

Vespa goes whizzing through the world propelled

by wings that in themselves do not appear capable of sustaining her weight in

the air. Nor were they capable but for the powerful motor that impels them with

such force and skill that they are apparently able to defy the attraction of

gravitation, and spurning the earth bear her aloft in the air.

The power that gives them their great force is found in certain thoracic muscles that throw the wings into such rapid vibrations they are able to play the part of aerial propellers, and away goes Vespa, merrily humming as she speeds along.

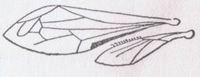

In structure and movement the wings of the wasp

are similar to those of the bee.

Like the bee, she has four of them, two on either side of the thorax and attached about half-way from the head to the abdomen, -- attached, one may be sure, at the point best to maintain the balance of the body when it is held suspended in the air.

The front wing is the larger, and the two are attached close together.

That these two wings may effectually act as one,

they are, like the bee's wings, hooked together. Along the upper edge of the

lower wing toward its outer margin, is a row of hooks that fit into a groove

running along the under edge of the upper wing.

That these two wings may effectually act as one,

they are, like the bee's wings, hooked together. Along the upper edge of the

lower wing toward its outer margin, is a row of hooks that fit into a groove

running along the under edge of the upper wing.

When the hooks are caught in the groove the wings are so closely locked together that the two look and act like one.

The wings of the true wasps differ from those of the diggers and of the bees by being folded, fan-like, down the middle.

This fold occurs in the large wings, and when the wasp is at rest with her fans closed she has an exceedingly slender and elegant-looking pair of wings lying along the sides of her body.

This lengthwise folding of the wings is convenient when Vespa crawls about the narrow spaces of her nest, and it more effectually disposes of them when they are not wanted than the bee's method of unhooking hers and slipping the under ones out of the way below the upper ones. Vespa does not seem to unhook her wings when at rest, but folds the under ones over at the joint without unhooking them. So her wing is in reality folded together like a little fan of three “sticks.”

Vespa hums as she flies, the sound being due to the rapid vibrations of her wings. At home, however, she is silent, her nest is not buzzing with happy industry; it is quiet with happy industry, and even when disturbed gives forth no such threatening murmur as pours from a disturbed bee-hive. There is excitement enough within, however, and out rush the frightened occupants, as eager to inflict punishment as though they had been as noisy in their wrath as their relatives.

When a wasp flies about one's face in an angry frame of mind it buzzes with loud vehemence, but as a community the Vespae rage in silence.

Like the bee, the wasp has a voice besides that made by the wing vibrations. If she is held between the thumb and forefinger by the thorax, the operator being careful what she is doing with her sting end meantime, a very distinct vibration of the whole thorax is felt. Indeed the head and the upper part of the legs share these curious motions, and a high-keyed buzzing is heard even when the wings are not moved at all.

Like the bee the wasp's “spiracles” or openings to the air-cavities in thorax and abdomen contain vocal organs, particularly those in the thorax, and when these are thrown into vibration they give rise to the shrill outcry of the captured insect. In the air-cavities of thorax and abdomen the blood is aerated as our own is in our lungs.

Concerning Vespa's voice, Moffett, an early English writer, in his entertaining “Theatre of Insects,” says,

“They make a sound as Bees do, but more fearful, hideous, terrible, and whisteling, especially when they are provoked to wrath.”

Evidently Mr. Moffett had had experience of them when “provoked to wrath,” and possibly the memory of their stings made him think ill of their voices.