THE

SETTLEMENT AT PLYMOUTH

"God had sifted

three kingdoms to find the wheat for this planting,

Then had sifted

the wheat as the living seed of a nation;

So say the

chronicles old, and such is the faith of the people."

|

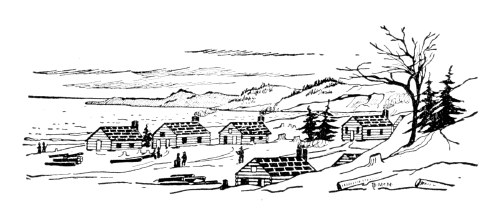

FOR purposes of convenience as well

as relationship the company was divided into nineteen families, as

before mentioned, each building their own house and residing together

therein.

Operations in this direction

commenced immediately upon their selection of a site and continued

throughout the winter.

To locate their respective houses

and to construct the same under the existing conditions, the winter

being intensely cold, was a great undertaking, and they labored amid

great hardships, though skillfully, with the timber near at hand.

Before spring they had constructed

two rows of houses, facing each other and stretching inland from a

point near the shore line, at the end of which was built by joint

effort a general storehouse in the centre of a barricaded plot of

ground.

Here they purposed keeping their

common belongings and the results of their labors in the field.

On 17th February a council was held

and Myles Standish, their only cavalier, appointed captain and vested

with power to maintain military rule. Standish was bred a soldier in

the Low Countries and had never enlisted in the army of Christ, but

joined the Puritans in England either through their desire to avail

themselves of his prowess or because of his own love of adventure and

excitement, as he might have presumed would be forthcoming from the

expedition to the new country.

In any event, he was willing to

plight his future with theirs, and proved a valuable addition to their

councils. Of irascible temper and just anger, he was irreproachable as

to integrity and devotion, and was well suited to the office.

Within a month of Standish assuming

command a lone red man came into Plymouth, saying, in good English,

"Welcome, Englishmen! Welcome, Englishmen!"

His name was Samoset, a Sagamore

from Monhegan, in the north, who had learned a few words of English

from the crews of the fishing vessels which had been in his

neighborhood. He was the first native to visit the settlers in their

new home, and, save by distant view, the first of his race that they

had come in contact with.

In a subsequent visit, made shortly

after, he brought with him another Indian, named Squanto, a native of

the same tribe, who had been kidnapped by Captain Hunt in 1614 and who

had been in England, whither he had been carried by his captor and

where he had picked up enough of the language to be able to converse

intelligently.

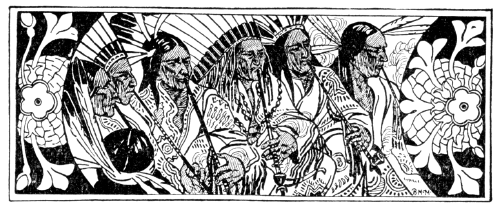

From him they learned that in the

neighborhood there were many tribes of red men, all under the dominion

of Massasoit, chief of the Wampanoags, who overran the southeasterly

portion of New England. On the first of April Massasoit appeared before

the settlers with sixty men, and in behalf of his allied tribes made an

offensive and defensive treaty, which guaranteed the settlers freedom

from molestation or annoyance, and which was strictly adhered to for

over half a century. It is likewise a significant fact that this colony

alone was thus favored with the good-will of the Indian, and standing

likewise alone in having kept faith with the native American.

The treaty also granted them lands

adjacent to the present location of the settlement, and the Indians

also sold them still more in the vicinity in anticipation of their

future needs.

The 5th April, 1621, saw the

departure of the Mayflower on her return voyage to

England. Yet another, sad and sorrowful parting. But with true

Christian fortitude and earnestness, though with a bitter

heart-longing, the little band that remained immediately set about

preparing the way for others yet to come.

During the past winter it is

recalled that one-half of the original number had succumbed to various

ills and disasters and now lay buried on the hilltop overlooking the

town, -- their graves covered with growing corn, that the natives might

not know to what numbers the little company had been reduced, and which

was still further lessened by the departure of the crew of the Mayflower,

who left at this time on the return voyage to England.

Among themselves there was little

dissension or variance to the general laws and rules laid down by the

councils. Whatever differences of individual opinions there may have

been, were for more moderate and less stringent views as regards their

form of self-government, and not in the least from any cause bearing

upon their ultimate object and unanimous desire -- the founding of a

new church in a new land. These minor considerations soon regulated

themselves, and by the early summer corn, barley, and peas were growing

as the result of their undivided attention to the details which made

their future not only possible but likewise an assured success.

Their early spring planting was

ably planned by the Indian, Squanto, who had become much enamored of

their good graces, and was intelligent and able in many respects beyond

any of his fellows.

Successful crops, generally,

rewarded their efforts at the coming of harvest, which having been

gotten in and housed in the common store, Governor Bradford sent men

with fowling-pieces into the wood to gun for wild turkey, which

abounded thereabouts, and who returned shortly with enough for a week's

supply for the common larder: Then followed a season of thanksgiving

and prayer, with much rejoicing at their present good fortune and the

fruits of their past labors. Within a year from the date of the arrival

of the Mayflower the second ship, the Fortune,

of fifty-five tons, anchored off Cape Cod on the 9th of November, 1621,

bringing recruits for the settlement and such additional supplies and

provender as the early voyagers were supposed to be in need of.

On board were thirty-five persons,

including Robert Cushman, many of them no doubt being of the party who

originally put back in the Speedwell. The Fortune

sailed from London early in July, but on account of

adverse winds did not clear the channel until the end of August,

thereby consuming four months on the voyage.

From the time of the departure of

the Mayflower in the April

previous up to the arrival of the Fortune in

November six more of their number had died, leaving but a mere fragment

of the original company to welcome the new comers. This influx,

however, did much to revive their tired spirits, and the winter passed

happily and comfortably amid new and enlarged plans for future

operations.

The following year another small

ship, the Anne, brought over still others, and

soon after their arrival the council decided to convey a detailed

report as to their progress and future prospects to the authorities in

England, and deputed Edward Winslow to make the report in person to the

representatives of the merchant adventurers in London.

Winslow sailed from New Plymouth in

the Anne on 18th September, and upon his arrival

in England made his report forthwith, with the result that further

provision was made for the fitting out of yet another expedition to

plant colonies in the vicinity of Plymouth Plantation, and more

especially at Cape Anne. Supplies were accordingly furnished for eighty

days for the use of the colony while transporting the additional

numbers thither, and the Charily was fitted out to

sail in March, 1622, and accompanied by Winslow as sponsor they set out

upon the track now so well laid down.

Aboard the Charity were shipped

several Devon cattle, the first ever brought into this country. And

here may be noted the fact of the vast quantity of Mayflower relics

which are supposed to exist even at the present day, the chief among

these being chairs, clocks, cradles, spinning-wheels, china, and

silverware. Without attempting to disparage the value or authenticity

of any heirlooms now in the possession of any one in particular, it is

well to remember the jocular statement that the Mayflower

must necessarily have been several times her actual size in order to

have brought all such into the country. Be this as it may, the

reference presumably holds good to the other ships which followed so

closely in the wake of the first voyage of the Mayflower. The

intending settlers were undoubtedly as well supplied with household

goods as their circumstances would seem to warrant, and in many cases

the reference is undoubtedly genuine, and the number of pieces which

exist to-day is probably large, even considering the ravages of time,

which is perhaps counterbalanced by the usual New England thrift, which

destroys nothing which may eventually become useful.

Luxuries, however, were not common

in their belongings, hence chairs, being considered luxuries and only

used by those high in the councils as a mark of rank, have proven

comparatively few in number, and teapots could not have been plentiful,

as an authority states that tea was worth $30 per pound at that time.

After a voyage approximating four

months, the usual length, the Charily arrived at Plymouth, and there

discharged a part of the company and the cattle, and taking on board

certain of the able men of the settlement and some hewn timber sailed

across the bay to Cape Anne. Here they proposed using the skill of the

forces at hand, and to speedily construct a new settlement on the lines

so successful at Plymouth.

They spent the winter here on a

rocky point of land, without the shelter of protecting hills and

forests, amid considerable hardship, and in the following spring

interest and enthusiasm in the future possibilities of the settlement

having languished to a considerable extent, the weakened remnant

removed and united with the contingent already located at Naumkeag, a

few miles distant.

The principal causes which led up

to the undertaking of the first voyage of the Mayflower, and

the subsequent voyages of other ships with the same ultimate object in

view, have been recounted herein. Their motives were not speculation,

excitement, or adventure, but the fundamental principle of freedom of

religious worship for their little hand of followers. This it was not

possible for them to find at home, and the final outcome had they

remained in Holland would have been vague and uncertain. Hence they

were of necessity obliged to roam, which, however, was set about with

that firm and earnest purpose which distinguished all previous acts of

the Puritans, and the after deeds of the Pilgrims.

The exodus opened a new era in the

history of the New World, and doubtless was the sowing of the seed

which afterward brought the colonists complete independence from the

rule of the Crown.

FINIS.

copyright, Kellscraft Studio

1999-2004

(Return to Web Text-ures)

|