| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2008 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

III

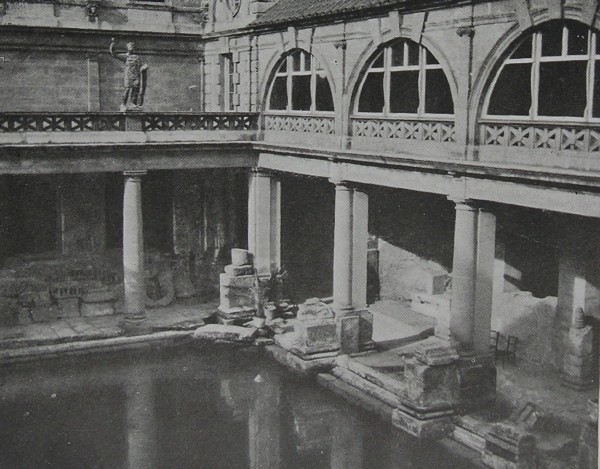

BATH AND ITS BATHS AT the risk of offending the somewhat sensitive guardians of the honour of Bath, the reflection shall be hazarded that the future of that city cannot hope to rival the glory of its past. In view of the vicissitudes of that past this may seem a daring prophecy. A chronicler of the early eighteenth century might have felt he was on sure ground in indulging in a similar forecast, only to have his gift of prevision made ridiculous by events which were still. to happen. Bath, indeed, has passed through three clearly-defined epochs of prosperity. The first of these dates far back to the period of the Roman occupation of Britain. Ignoring as little better than idle legends such stories as are told of British precursers, it seems established beyond dispute that the earliest to lay the foundations of a considerable city in this "warm vale" of the West were the triumphant masters of the old world. In dealing with such a remote period of history it cannot be expected that any hard and fast date shall be available, and yet it seems likely that the advent of the Romans may be placed somewhere about the year 45 of our era. It was in the early years of the reign of Claudius, that mild and amiable occupant of the Cæsars' throne, that a Roman legion is recorded to have made a complete conquest of this part of Somersetshire. To this period, then, it is usual to "attribute the first foundation of Bath, when the Romans, attracted by the appearance of those hot springs, whose uses they so well knew and so highly valued, fixed upon the low and narrow vale in which they rose for the establishment of a station and the erection of a town." For nearly four centuries the power of Rome was supreme in this sequestered dale of the West. Upon the rude foundations of the city reared about the year 45 subsequent rulers from the city by the Tiber upraised luxurious villas and stately temples. Due attention having been given by early comers to the military defences of the place, its subsequent and more leisurely adornment followed as the natural expression of the Roman temperament. "The elegant Agricola," surmises a local historian, "reposing a winter here from his successful campaign in Wales, would, in pursuance of his customary policy, decorate it with buildings, dedicated to piety and pleasure; and the polite Adrian, thirty years afterwards, founded an establishment in it, which at once rendered it the most important place in the southern part of Britain. This was Fabrica, or College of Armourers, in which the military weapons for the use of the legions were manufactured." A CORNER OF THE BATHS Thus it is not difficult for the imagination to trace that transformation of Bath into a miniature Rome which was repeated so often in the subject provinces of the empire. And there is another factor which demands special attention in the present case. The Roman was a confirmed devotee of the bath. No city of his was complete without its Thermæ, the meeting-place for the idle as well as the halls for ablution. An essential feature of these institutions was the underground furnace by which the water was heated, but at Bath the Romans were spared the expense and labour of furnace-constructing owing to the abundant waters issuing from their springs already hot. Under such circumstances of unusual good fortune it is not surprising that, in addition to the baths themselves, the most notable building reared here was a Temple of Minerva. It was erected on the site of the Pump-room of to-day, and considerable remains of its beautiful masonry were brought to light years ago and may still be seen in the Royal Literary Institution of the city. These relics include the tympanum of the Temple, and substantial fragments of columns, cornices and pilasters, all testifying to the elegance and superb workmanship of a building which cannot have had its equal in all Britain. Nor are these the only surviving vestiges of the Roman occupation of Bath. Keeping them silent company are pediments, and portals, and votive altars and monumental stones. From the time-worn inscriptions on these altars can be pieced together that gratitude for recovered health which was doubtless so fresh and sincere in those far-off years, but which sounds like a grim satire on human self-importance now that health and life itself matters so little; and this page of the dim past is fitly rounded off by the medicine stamp of a Roman quack which records that it was "the Phœburn (or Blistering Collyrium) of T. Junianus for such hopeless cases as have been given up by the Physicians." Alas for T. Junianus, who is himself now in a far more hopeless case than any of those credulous patients who pinned their faith to his Blistering Collyrium! For the beauty of its situation, the healing properties of its copious springs, and the social amenities it offered, Bath was no doubt exceedingly popular with the Roman soldiers and governors. Such a city must have offered liberal compensations for the exile even from Italy. In hardly any other outpost of the empire could life have held so many elements of pleasure. Yet, as the fifth century opened, the premonitions of coming changes must have cast a gloom over this happy Roman community. Internal decay and the assaults of the barbarians on the Western Empire were sapping the power which had so long held the nations in bondage. As each of the swift and tremendous blows of Alaric crippled the strength of Rome the necessity grew ever urgent for the withdrawal of the legions from the remote frontiers of the empire, and thus it came to pass that soon after the fifth century had entered upon its second decade the Roman masters of Britain sailed away from its shores for ever. So closed the first prosperous epoch in the history of Bath. And now came the centuries of adversity. Left to their own resources after enjoying for so long the protection of Roman arms, the natives of Britain became the prey of the Saxon and Danish hordes which poured into the land from over the North Sea. Many of these plundering bands penetrated to this fair West country and Bath itself became the centre of frequent and fierce conflict. To these years belong the exploits of arms with which romance and poetry have enhaloed the shadowy figure of Arthur and his knights of the Round Table, and some authorities have identified Bath with the prince's famous victory over the Saxons at Mons Badonicus in 520. But the prowess of Arthur or other native warriors was in vain; as the sixth century was waning an irresistible army of Saxons swept down on Somersetshire, overthrew the Britons at Deorham, eight miles from Bath, and firmly established Saxon ascendency where the Romans had so long made their home. With this conquest there broke the dawn of a second era of prosperity for "the city in the warm vale." And now the Roman name of Aquæ Solis gradually gave way to the Hæt Bathen — "hot baths" — of the Saxons, to be abbreviated in the unborn centuries to the one significant word of to-day. Save for an interregnum of misfortune during the raids of the Danes, Bath enjoyed many tokens of royal favour under the rule of the Saxons. Osric founded a convent here in 676; Athelstan established a mint within its walls; and Edgar, in 973, chose the city as the scene of a pageant of unprecedented splendour. "Condemned by Archbishop Dunstan," so the story goes, "to atone for an offence against the church, he was restricted from wearing his crown in public for the space of seven years; but, when this ecclesiastical censure was satisfied, he selected Bath as the place where his forgiveness should be published, by the splendid and gorgeous ceremony of his coronation." For several centuries after the Norman conquest Bath sinks into the background of English history. It emerges from obscurity for a brief space now and then, as when it was plundered by Geoffrey of Contance, and when, in 1574, it was honoured by a visit from Queen Elizabeth; but in the main the city slumbered peacefully on in its picturesque vale, untroubled by visions of the years of fame which were drawing near. Towards the close of the seventeenth century the outward aspect of the city gave little promise of the golden era which was soon to dawn. Although it had long been the seat of a bishop, and was resorted to by the sick for its springs, Bath was then, Macaulay says, "a maze of only four or five hundred houses, crowded within an old wall in the vicinity of the Avon. . . . That beautiful city which charms even eyes familiar with the masterpieces of Bramante and Palladio, and which the genius of Anstey and of Smollett, of Frances Burney and of Jane Austen, has made classic ground, had not begun to exist. Milsom Street itself was an open field lying far beyond the walls; and hedgerows intersected the space which is now covered by the Crescent and the Circus. The poor patients to whom the waters had been recommended lay on straw in a place which, to use the language of a contemporary physician, was a covert rather than a lodging." BATH, FROM THE AVON Some fifty years later a marvellous change had taken place. To whom belongs the credit? or to what particular incident was it due? Bathonians and others have been exercised with those questions for a long time. Now and then the discussion has waxed hot and furious, and it ill becomes an outsider to venture into the mêlèe. Yet a dispassionate survey of the situation reveals several instructive facts. One of these is that the visit, in 1687, of the Queen of James II. directed attention to the waters of Bath as a probable remedy for barrenness; a second is that the sojourn of Queen Anne in 1702 raised the city in social esteem; and a third introduces the claims of Beau Nash and John Wood. Here debatable ground is reached. Social England was ripe for a change. "People of fashion," as Goldsmith relates, "had no agreeable summer retreat from the town," and the claims of Bath were handicapped by the fact that the amusements "were neither elegant, nor conducted with delicacy." Manners in general were at a discount, and "the lodgings for visitors were paltry, though expensive." Nor was this all. Such reputation as the city possessed was founded upon its healing waters, and that reputation was in serious danger. One of the leading physicians of the age, in revenge for affronts offered him at Bath, declared that he would write a pamphlet which would "cast a toad into the spring." Such was the condition of the city at the advent of Beau Nash in 1703. That some twenty-five years later Bath had become the social centre of England, and had entered upon a century of unrivalled prosperity, is often placed to his credit. To him, it is asserted, the city "must mainly attribute the rapidity with which it sprang from an insignificant place into the focus of fashionable life, the most 'pleasurable' city in the Kingdom." It is well that this eulogy is qualified, but the qualification would have been more to the point had it been increased in emphasis and laid stress upon the name of John Wood. The latter was no Master of the Ceremonies; he was just a plain builder; but if destiny had not ordained his arrival on the scene at this crisis not all Nash's solemnity in "adjusting trifles" would have availed to start Bath on its career of prosperity. Yet, in claiming justice for Wood, it is imperative that due praise be also given to another of the creators of modern Bath. Indeed, when all the facts are considered, it is impossible to resist the conclusion that this other man, Ralph Allen by name, deserves more of the credit of the city's golden era than either Nash or Wood. Allen, a son of lowly parents, was but a youth when he settled in Bath as a post office assistant. His integrity, industry and ability soon marked him out for advancement, and in 1720 he promulgated a scheme of postal service for England which, adopted by the government, yielded him a yearly income of twelve thousand pounds. He was also interested in another enterprise which had more momentous results for the city of his adoption. Acquiring some large quarries near Bath, he conceived the idea of exploiting the peculiar stone of those quarries for building purposes, and it was in the carrying out of that scheme he called Wood to his aid. One of the greatest needs of the city was more adequate private buildings, without which the social interest in the place would speedily have died out, and that that need was met on such noble lines as are testified by the present aspect of Bath was due to the initiative of Allen aided by the executive skill of Wood and his son. Nor

should it be overlooked that in other respects Allen deserves well of

Bath. Not only did he take an alert interest in its municipal

government, and contribute generously to all worthy public

institutions, but his love of hospitality was the means of bringing

many illustrious visitors to the city. At his mansion of Prior Park

he received a constant succession of famous guests, including

Fielding, and Pope, and Mason, and Lord Chatham and the younger Pitt.

So long as English literature endures Allen is secure in remembrance.

Pope has enshrined his memory in the lines. "Let

humble Allen, with an awkward shame,

Do good by stealth, and blush to find it fame."

It is true the poet later in life grew cold towards his generous friend, and left him £150 in his will, that sum "being, to the best of my calculation, the account of what I have received from him, partly for my own, and partly for charitable uses;" but the implied satire of that bequest was robbed of its point by Allen remarking, "He forgot to add the other 0 to the 150," and sending the money to the city hospital. SITE OF HYPOCAUST BATH  THE ROMAN BATHS Fielding appears to have been a frequent and ever welcome guest at Prior Park, and nobly did he repay Allen's hospitality by portraying his unselfish character in Squire Allworthy in "Tom Jones," and by inscribing "Amelia" to him as a "small token" of his love and gratitude ,and respect. When the great novelist passed away, Allen undertook the charge of his children, paid for their education and remembered them generously in his will. BATH ABBEY No

one can muse upon the history of Bath from 1725 onwards. without

being impressed by the countless shades of illustrious men and women

who appear to walk its streets and haunt its buildings. Some of

these, though not the most notable, found a final resting-place in

the historic Abbey, which is so densely crowded with the memorials of

the dead as to. excuse the epigram:

"These

walls, so full of monument and bust,

Shew how Bath-waters serve to lay the dust."

Beau

Nash is of those buried here; another is James Quin, the actor, who

declared he did not know a better place than Bath for an old cock to

roost in. It was from this city that Quin sent his famous note to his

manager Rich. The actor had quarrelled with the manager, but in a

milder mood held out a tentative olive-branch in the laconic message:

"I am at Bath. Yours, James Quin," only to receive the curt

reply, "Stay

there and be damned. Yours, John Rich."

Wherever the visitor wanders in these streets, streets from which the tide of fashionable life has largely receded, he cannot escape memories of the men and women who made the fame of the late eighteenth century. Thomas Gainsborough is here, so busy with his sitters that his "house became gains' borough; "and Edmund Burke, come on a last vain quest for health; and Nelson, so renewed in strength that he would have all his sick friends join him; and the young Walter Scott, who was to carry away as his most abiding impression his first experience of the theatre; and Horace Walpole, so bored with the place that he could only "sit down by the waters of Babylon and weep, when I think of thee, oh Strawberry!"; and James Wolfe, seeking strength for his enfeebled body on the eve of setting his face towards Quebec and glory; and the Countess of Huntingdon, busy with her arrogant letters to the ministers of her sect; and Oliver Goldsmith, and Samuel Johnson, and countless other immortals. Other sons and daughters of fame were to enrich the associations of Bath in the opening half of the nineteenth century. Hither, as the century dawned, came the gentle Jane Austen, to reap the quiet harvest of an observing eye and garner its fruits in many a later page. Nor should the solitary figure of "Vathek" Beckford be forgotten, the rich and gifted misanthrope who made so barren a use of his wealth and his genius. Late in the procession, too, comes the grand and picturesque shade of Walter Savage Landor, a familiar figure in the streets of Bath for many a year. These children of genius have all passed on, and none have succeeded them. But for their sake, and because of its storied past, Bathonia, the "city of the warm vale," will ever hold its place of pride in the annals of England. |