| Web

and Book design, |

Click

Here to return to |

|

CHAPTER

XVI. ABOU

SIMBEL. WE came

to

Abou Simbel on the night of the 31st of January, and we left

at sunset on the 18th of February. Of these eighteen clear days, we

spent

fourteen at the foot of the rock of the great temple, called in the old

Egyptian tongue the Rock of Abshek. The remaining four (taken at the

end of the

first week and the beginning of the second) were passed in the

excursion to

Wady-Halfeh and back. By thus dividing the time, our long sojourn was

made less

monotonous for those who had no especial work to do. Meanwhile,

it was wonderful to wake every morning close under the steep

bank, and, without lifting one’s head from the pillow, to see

that row of giant

faces so close against the sky. They showed unearthly enough by

moonlight; but

not half so unearthly as in the grey of dawn. At that hour, the most

solemn of

the twenty-four, they wore a fixed and fatal look that was little less

than

appalling. As the sky warmed, this awful look was succeeded by a flush

that

mounted and deepened like the rising flush of life. For a moment they

seemed to

glow – to smile – to be transfigured. Then came a

flash, as

of thought itself.

It was the first instantaneous flash of the risen sun. It lasted less

than a

second. It was gone almost before one could say that it was there. The

next

moment, mountain, river, and sky were distinct in the steady light of

day; and

the colossi – mere colossi now – sat serene and

stony in

the open sunshine. Every

morning I waked in time to witness that daily miracle. Every

morning I saw those awful brethren pass from death to life, from life

to

sculptured stone. I brought myself almost to believe at last that there

must

sooner or later come some one sunrise when the ancient charm would snap

asunder, and the giants must arise and speak. Stupendous

as they are, nothing is more difficult than to see the

colossi properly. Standing between the rock and the river, one is too

near;

stationed on the island opposite, one is too far off; while from the

sand-slope

only a side-view is obtainable. Hence, for want of a fitting

standpoint, many

travellers have seen nothing but deformity in the most perfect face

handed down

to us by Egyptian art. One recognises in it the negro, and one the

Mongolian

type;1 while

another admires the fidelity with which

“the Nubian

characteristics” have been seized. Yet, in

truth, the head of the young Augustus is not cast in a loftier

mould. These statues are portraits – portraits of the same

man

four times

repeated; and that man is Rameses the Great. Now, Rameses the Great, if he was as much like his portraits as his portraits are like each other, must have been one of the handsomest men, not only of his day, but of all history. Wheresoever we meet with him, whether in the fallen colossus at Memphis, or in the syenite torso of the British Museum, or among the innumerable bas-reliefs of Thebes, Abydos, Gournah, and Bayt-el-Welly, his features (though bearing in some instances the impress of youth and in others of maturity) are always the same. The face is oval; the eyes are long, prominent, and heavy-lidded; the nose is slightly aquiline and characteristically depressed at the tip; the nostrils are open and sensitive; the under lip projects; the chin is short and square.

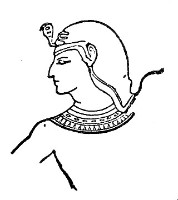

The

annexed woodcut gives the profile of the southernmost colossus,

which is the only perfect, or very nearly perfect, one of the four. The

original can be correctly seen from but one point of view; and that

point is

where the sandslope meets the northern buttress of the

façade,

at a level just

parallel with the beards of the statues. It was thence that the present

outline

was taken. The sandslope is steep, and loose, and hot to the feet. More

disagreeable climbing it would be hard to find even in Nubia; but no

traveller

who refuses to encounter this small hardship need believe that he has

seen the

faces of the colossi.

Viewed

from below, this beautiful portrait is foreshortened out of all

proportion. It looks unduly wide from ear to ear, while the lips and

lower part

of the nose show relatively larger than the rest of the features. The

same may

be said of the great cast in the British Museum. Cooped up at the end

of a

narrow corridor and lifted not more than fifteen feet above the ground,

it is

carefully placed so as to be wrong from every point of view and shown

to the

greatest possible disadvantage. The

artists who wrought the original statues were, however, embarrassed

by no difficulties of focus, daunted by no difficulties of scale.

Giants themselves,

they summoned these giants from out the solid rock, and endowed them

with

superhuman strength and beauty. They sought no quarried blocks of

syenite or

granite for their work. They fashioned no models of clay. They took a

mountain,

and fell upon it like Titans, and hollowed and carved it as though it

were a

cherry-stone, and left it for the feebler men of after-ages to marvel

at

forever. One great hall and fifteen spacious chambers they hewed out

from the

heart of it; then smoothed the rugged precipice towards the river, and

cut four

huge statues with their faces to the sunrise, two to the right and two

to the

left of the doorway, there to keep watch to the end of time. These

tremendous warders sit sixty-six feet high, without the platform

under their feet. They measure across the chest 25 feet and 4 inches;

from the

shoulder to the elbow, 15 feet and 6 inches; from the inner side of the

elbow

joint to the tip of the middle finger, 15 feet; and so on, in relative

proportion. If they stood up, they would tower to a height of at least

83 feet,

from the soles of their feet to the tops of their enormous

double-crowns. Nothing

in

Egyptian sculpture is perhaps quite so wonderful as the way

in which these Abou Simbel artists dealt with the thousands of tons of

material

to which they here gave human form. Consummate masters of effect, they

knew

precisely what to do, and what to leave undone. These were portrait

statues;

therefore they finished the heads up to the highest point consistent

with their

size. But the trunk and the lower limbs they regarded from a decorative

rather

than a statuesque point of view. As decoration, it was necessary that

they

should give size and dignity to the façade. Everything,

consequently, was here

subordinated to the general effect of breadth, of massiveness, of

repose.

Considered thus, the colossi are a triumph of treatment. Side by side

they sit,

placid and majestic, their feet a little apart, their hands resting on

their

knees. Shapely though they are, those huge legs look scarcely inferior

in girth

to the great columns of Karnak. The articulations of the knee-joint,

the swell

of the calf, the outline of the peroneus

longus

are indicated rather than developed. The toe-nails

and

toe-joints are given in the same bold and general way; but the fingers,

because

only the tips of them could be seen from below, are treated en bloc.

Their

faces show the same largeness of style. The little dimple which

gives such sweetness to the corners of the mouth, and the tiny

depression in

the lobe of the ear, are in fact circular cavities as large as saucers.

How far

this treatment is consistent with the most perfect delicacy and

even finesse of execution, may be gathered from the sketch. The nose

there

shown in profile is 3 feet and a half in length; the mouth so

delicately curved

is about the same in width; even the sensitive nostril, which looks

ready to

expand with the breath of life, exceeds 8 inches in length. The ear

(which is

placed high, and is well detached from the head) measures 3 feet and 5

inches

from top to tip. A recent

writer,2 who

brings sound practical knowledge to

bear upon the subject, is of opinion that the Egyptian sculptors did

not even

“point” their work beforehand. If so, then the

marvel is

only so much the

greater. The men who, working in so coarse and friable a material,

could not

only give beauty and finish to heads of this size, but could with

barbaric

tools hew them out ab initio

from

the natural rock, were the Michael Angelos of their age. It has

already been said that the last Rameses to the southward is the

best preserved. His left arm and hand are injured, and the head of the

uræus

sculptured on the front of the pschent is gone; but with these

exceptions the

figure is as whole, as fresh in surface, as sharp in detail, as on the

day it

was completed. The next is shattered to the waist. His head lies at his

feet,

half buried in sand. The third is nearly as perfect as the first; while

the

fourth has lost not only the whole beard and the greater part of the

uræus, but

has both arms broken away, and a big, cavernous hole in the front of

the body.

From the double-crowns of the two last, the top ornament is also

missing. It

looks a mere knob; but it measures eight feet in height. Such an

effect does the size of these four figures produce on the mind

of the spectator, that he scarcely observes the fractures they have

sustained.

I do not remember to have even missed the head and body of the

shattered one,

although nothing is left of it above the knees. Those huge legs and

feet covered

with ancient inscriptions,3 some

of Greek, some of

Phœnician origin,

tower so high above the heads of those who look at them from below,

that one

scarcely thinks of looking higher still. The

figures are naked to the waist, and clothed in the usual striped

tunic. On their heads they wear the double-crown, and on their necks

rich

collars of cabochon drops cut in very low relief. The feet are bare of

sandals,

and the arms of bracelets; but in the front of the body, just where the

customary belt and buckle would come, are deep holes in the stone, such

as

might have been made to receive rivets, supposing the belts to have

been made

of bronze or gold. On the breast, just below the necklace, and on the

upper

part of each arm, are cut in magnificent ovals, between four and five

feet in

length, the ordinary cartouches of the king. These were probably

tattooed upon

his person in the flesh. Some

have

supposed that these statues were originally coloured, and that

the colour may have been effaced by the ceaseless shifting and blowing

of the

sand. Yet the drift was probably at its highest when Burckhardt

discovered the

place in 1813; and on the two heads that were still above the surface,

he seems

to have observed no traces of colour. Neither can the keenest eye

detect any

vestige of that delicate film of stucco with which the Egyptians

invariably

prepared their surfaces for painting. Perhaps the architects were for

once

content with the natural colour of the sandstone, which is here very

rich and

varied. It happens also that the colossi come in a light-coloured vein

of the

rock, and so sit relieved against a darker background. Towards noon,

when the

level of the façade has just passed into shade and the

sunlight

still strikes

upon the statues, the effect is quite startling. The whole thing, which

is then

best seen from the island, looks like a huge onyx-cameo cut in high

relief. A statue

of Ra,4 to

whom the temple is dedicated, stands some

twenty feet high in a niche over the doorway, and is supported on

either side

by a bas-relief portrait of the king in an attitude of worship. Next

above

these comes a superb hieroglyphic inscription reaching across the whole

front;

above the inscription, a band of royal cartouches; above the

cartouches, a

frieze of sitting apes; above the apes, last and highest, some

fragments of a

cornice. The height of the whole may have been somewhat over a hundred

feet.

Wherever it has been possible to introduce them as decoration, we see

the ovals

of the king. Under those sculptured on the platforms and over the door,

I

observed the hieroglyphic character The

relative position of the two temples of Abou Simbel has been already

described – how they are excavated in two adjacent mountains

and

divided by a

cataract of sand. The front of the small temple lies parallel to the

course of

the Nile, here flowing in a north-easterly direction. The

façade

of the great temple is cut in the flank of the mountain, and faces due east. Thus

the

colossi, towering above the shoulder of the sand-drift, catch, as it

were, a

side view of the small temple and confront vessels coming up the river.

As for

the sand-drift, it curiously resembles the glacier of the Rhone. In

size, in

shape, in position, in all but colour and substance, it is the same.

Pent in

between the rocks at top, it opens out like a fan at bottom. In this

its

inevitable course, it slants downward across the façade of

the great temple.

For ever descending, drifting, accumulating, it wages the old stealthy

war;

and, unhasting, unresting, labours grain by grain to fill the hollowed

chambers, and bury the great statues, and wrap the whole temple in a

winding-sheet

of golden sand, so that the place thereof shall know it no more. It had

very nearly come to this when Burckhardt went up (A.D. 1813). The

top of the doorway was then thirty feet below the surface. Whether the

sand

will ever reach that height again, must depend on the energy with which

it is

combated. It can only be cleared as it accumulates. To avert it is

impossible.

Backed by the illimitable wastes of the Libyan desert, the supply from

above is

inexhaustible. Come it must; and come it will, to the end of time. The

drift

rose to the lap of the northernmost colossus and half-way up

the legs of the next, when the Philæ lay at Abou Simbel. The

doorway was clear,

however, almost to the threshold, and the sand inside was not more than

two

feet deep in the first hall. The whole façade, we were told,

had

been laid

bare, and the interior swept and garnished, when the Empress of the

French,

after opening the Suez Canal in 1869, went up the Nile as far as the

Second

Cataract. By this time, most likely, that yellow carpet lies thick and

soft in

every chamber, and is fast silting up the doorway again. How well

I

remember the restless excitement of our first day at Abou

Simbel! While the morning was yet cool, the painter and the writer

wandered to

and fro, comparing and selecting points of view, and superintending the

pitching of their tents. The painter planted his on the very brink of

the bank,

face to face with the colossi and the open doorway. The writer perched

some

forty feet higher on the pitch of the sandslope; so getting a side-view

of the

façade, and a peep of distance looking up the river.6

To

fix the

tent up there was no easy matter. It was only by sinking the tent-pole

in a

hole filled with stones, that it could be trusted to stand against the

steady

push of the north wind, which at this season is almost always blowing. Meanwhile

the travellers from the other dahabeeyahs were tramping

backwards and forwards between the two temples; filling the air with

laughter,

and waking strange echoes in the hollow mountains. As the day wore on,

however,

they returned to their boats, which one by one spread their sails and

bore away

for Wady Halfeh. When

they

were fairly gone and we had the marvellous place all to

ourselves, we went to see the temples. The

smaller one, though it comes first in the order of sailing, is

generally seen last; and seen therefore to disadvantage. To eyes fresh

from the

“Abode of Ra,” the “Abode of

Hathor” looks less

than its actual size; which is

in fact but little inferior to that of the temple at Derr. A first

hall,

measuring some 40 feet in length by 21 in width, leads to a transverse

corridor, two side-chambers, and a sanctuary 7 feet square, at the

upper end of

which are the shattered remains of a cow-headed statue of Hathor. Six

square

pillars, as at Derr, support what, for want of a better word, one must

call the

ceiling of the hall; though the ceiling is in truth the superincumbent

mountain. In this

arrangement, as in the general character of the bas-relief

sculptures which cover the walls and pillars, there is much simplicity,

much

grace, but nothing particularly new. The façade, on the

contrary, is a daring

innovation. To those who have not seen the place the annexed

illustration is

worth pages of description; and to describe it in words only would be

difficult. Here the whole front is but a frame for six recesses, from

each of

which a colossal statue, erect and life-like, seems to be walking

straight out

from the heart of the mountain. These statues, three to the right and

three to

the left of the doorway, stand thirty feet high, and represent Rameses

II and

Nefertari, his queen. Mutilated as they are, the male figures are full

of

spirit, and the female figures full of grace. The queen wears on her

head the

plumes and disk of Hathor. The king is crowned with the pschent, and

with a

fantastic helmet adorned with plumes and horns. They have their

children with

them; the queen her daughters, the king his sons – infants of

ten

feet high,

whose heads just reach to the parental knee. The

walls

of these six recesses, as they follow the slope of the

mountain, form massive buttresses, the effect of which is wonderfully

bold in

light and shadow. The doorway gives the only instance of a porch that

we saw in

either Egypt or Nubia. The superb hieroglyphs which cover the faces of

these

buttresses and the front of this porch are cut half-a-foot deep into

the rock,

and are so large that they can be read from the island in the middle of

the

river. The tale they tell – a tale retold, in many varied

turns

of old Egyptian

style upon the architraves within – is singular and

interesting. “Rameses,

the Strong in Truth, the Beloved of Amen,” says the outer

legend, “made this divine Abode6

for his royal wife,

Nefertari, whom

he loves.” The

legend

within, after enumerating the titles of the King, records

that “his royal wife who loves him, Nefertari the Beloved of

Maut, constructed

for him this Abode in the mountain of the Pure Waters.” On every

pillar, in every act of worship pictured on the walls, even in

the sanctuary, we find the names of Rameses and Nefertari

“coupled and

inseparable.” In this double dedication, and in the unwonted

tenderness of the

style, one seems to detect traces of some event, perhaps of some

anniversary,

the particulars of which are lost for ever. It may have been a meeting;

it may

have been a parting; it may have been a prayer answered, or a vow

fulfilled. We

see, at all events, that Rameses and Nefertari desired to leave behind

them an

imperishable record of the affection which united them on earth, and

which they

hoped would reunite them in Amenti. What more do we need to know? We

see that

the queen was fair; 7 that

the king was in his prime. We

divine the

rest; and the poetry of the place at all events is ours. Even in these

barren

solitudes there is wafted to us a breath from the shores of old

romance. We

feel that Love once passed this way, and that the ground is still

hallowed

where he trod. We

hurried

on to the great temple, without waiting to examine the lesser

one in detail. A solemn twilight reigned in the first hall, beyond

which all

was dark. Eight colossi, four to the right and four to the left, stand

ranged

down the centre, bearing the mountain on their heads. Their height is

twenty-five feet. With hands crossed on their breasts, they clasp the

flail and

crook; emblems of majesty and dominion. It is the attitude of Osiris,

but the

face is the face of Rameses II. Seen by this dim light, shadowy,

mournful,

majestic, they look as if they remembered the past. Beyond

the

first hall lies a second hall supported on four square

pillars; beyond this again, a transverse chamber, the walls of which

are

covered with coloured bas-reliefs of various gods; last of all, the

sanctuary.

Here, side by side, sit four figures larger than life – Ptah,

Amen-Ra, Ra, and

Rameses deified. Before them stands an altar, in shape a truncated

pyramid, cut

from the solid rock. Traces of colour yet linger on the garments of the

statues; while in the walls on either side are holes and grooves such

as might

have been made to receive a screen of metal-work. The air

in

the sanctuary was heavy with an acrid smoke, as if the

priests had been burning some strange incense and were only just gone.

For this

illusion we were indebted to the visitors who had been there before us.

They

had lit the place with magnesian wire; the vapour of which lingers long

in

these unventilated vaults. To

settle

down then and there to a steady investigation of the

wall-sculptures was impossible. We did not attempt it. Wandering from

hall to

hall, from chamber to chamber; now trusting to the faint gleams that

straggled

in from without, now stumbling along by the light of a bunch of candles

tied to

the end of a stick, we preferred to receive those first impressions of

vastness, of mystery, of gloomy magnificence, which are the more

profound for

being somewhat vague and general. Scenes

of

war, of triumph, of worship, passed before our eyes like the

incidents of a panorama. Here the king, borne along at full gallop by

plumed

steeds gorgeously caparisoned, draws his mighty bow and attacks a

battlemented

fortress. The besieged, some of whom are transfixed by his tremendous

arrows,

supplicate for mercy. They are a Syrian people, and are by some

identified with

the Northern Hittites. Their skin is yellow; and they wear the long

hair and

beard, the fillet, the rich robe, fringed cape, and embroidered baldric

with

which we are familiar in the Nineveh sculptures. A man driving off

cattle in

the foreground looks as if he had stepped out of one of the tablets in

the

British Museum. Rameses meanwhile towers, swift and godlike, above the

crowd.

His coursers are of such immortal strain as were the coursers of

Achilles. His

sons, his whole army, chariot and horse, follow headlong at his heels.

All is movement

and the splendour of battle. Farther

on, we see the King returning in state, preceded by his

prisoners of war. Tied together in gangs, they stagger as they go, with

heads

thrown back and hands uplifted. These, however, are not Assyrians, but

Abyssinians

and Nubians, so true to the type, so thick-lipped, flat-nosed, and

woolly-headed, that only the pathos of the expression saves them from

being

ludicrous. It is naturalness pushed to the verge of caricature. A little

farther still, and we find Rameses leading a string of these

captives into the presence of Amen-Ra, Maut, and Khons –

Amen-Ra

weird and

unearthly, with his blue complexion and towering plumes; Maut wearing

the crown

of Upper Egypt; Khons by a subtle touch of flattery depicted with the

features

of the king. Again, to right and left of the entrance, Rameses, thrice

the size

of life, slays a group of captives of various nations. To the left

Amen-Ra, to

the right Ra Harmachis,8 approve

and accept the sacrifice.

In the

second hall we see, as usual, the procession of the sacred bark. Ptah,

Khem,

and Bast, gorgeous in many-coloured garments, gleam dimly, like figures

in

faded tapestry, from the walls of the transverse corridor. But the

wonder of Abou Simbel is the huge subject on the north side of

the great hall. This is a monster battle-piece which covers an area of

57 feet

and 7 inches in length, by 25 feet 4 inches in height, and contains

over 1100

figures. Even the heraldic cornice of cartouches and asps which runs

round the

rest of the ceiling is omitted on this side, so that the wall is

literally

filled with the picture from top to bottom. Fully to

describe this huge design would take many pages. It is a

picture-gallery in itself. It represents not a single action but a

whole

campaign. It sets before us, with Homeric simplicity, the pomp and

circumstance

of war, the incidents of camp life, and the accidents of the open

field. We see

the enemy’s city with its battlemented towers and triple

moat;

the besiegers’

camp and the pavilion of the king; the march of infantry; the shock of

chariots; the hand-to-hand melée; the flight of the

vanquished;

the triumph of

Pharaoh; the bringing in of the prisoners; the counting of the hands of

the

slain. A great river winds through the picture from end to end, and

almost

surrounds the invested city. The king in his chariot pursues a crowd of

fugitives along the bank. Some are crushed under his wheels; some

plunge into

the water and are drowned.9 Behind

him, a moving wall of

shields

and spears, advances with rhythmic step the serried phalanx; while

yonder,

where the fight is thickest, we see chariots overturned, men dead and

dying,

and riderless horses making for the open. Meanwhile the besieged send

out

mounted scouts, and the country folk drive their cattle to the hills. A grand

frieze of chariots charging at full gallop divides the subject

lengthwise, and separates the Egyptian camp from the field of battle.

The camp

is square, and enclosed, apparently, in a palisade of shields. It

occupies less

than one sixth part of the picture, and contains about a hundred

figures.

Within this narrow space the artist has brought together an astonishing

variety

of incidents. The horses feed in rows from a common manger, or wait

their turn

and impatiently paw the ground. Some are lying down. One, just

unharnessed,

scampers round the enclosure. Another, making off with the empty

chariot at his

heels, is intercepted by a couple of grooms. Other grooms bring buckets

of

water slung from the shoulders on wooden yokes. A wounded officer sits

apart,

his head resting on his hand; and an orderly comes in haste to bring

him news

of the battle. Another, hurt apparently in the foot, is having the

wound

dressed by a surgeon. Two detachments of infantry, marching out to

reinforce

their comrades in action, are met at the entrance to the camp by the

royal

chariot returning from the field. Rameses drives before him some

fugitives, who

are trampled down, seized, and despatched upon the spot. In one corner

stands a

row of objects that look like joints of meat; and near them are a small

altar

and a tripod brazier. Elsewhere, a couple of soldiers, with a big bowl

between

them, sit on their heels and dip their fingers in the mess, precisely

as every

Fellah does to this day. Meanwhile it is clear that Egyptian discipline

was

strict, and that the soldier who transgressed was as abjectly subject

to the

rule of stick as his modern descendant. In no less than three places do

we see

this time-honoured institution in full operation, the superior officer

energetically

flourishing his staff; the private taking his punishment with

characteristic

disrelish. In the middle of the camp, watched over by his keeper, lies

Rameses’

tame lion; while close against the royal pavilion a hostile spy is

surprised

and stabbed by the officer on guard. The pavilion itself is very

curious. It is

evidently not a tent but a building, and was probably an extemporaneous

construction of crude brick. It has four arched doorways, and contains

in one

corner an object like a cabinet, which two sacred hawks for supporters.

This

object, which is in fact almost identical with the hieroglyphic emblem

used to

express a royal panegyry or festival, stands, no doubt, for the private

oratory

of the King. Five figures kneel before it in adoration. To

enumerate all or half the points of interest in this amazing picture

would ask altogether too much space. Even to see it, with time at

command and

all the help that candles and magnesian torches can give, is far from

easy. The

relief is unusually low, and the surface, having originally been

covered with

stucco, is purposely roughened all over with tiny chisel-marks, which

painfully

confuse the details. Nor is this all. Owing to some kind of saline ooze

in that

part of the rock, the stucco has not only peeled off, but the actual

surface is

injured. It seems to have been eaten away, just as iron is eaten by

rust. A few

patches adhere, however, in places, and retain the original colouring.

The

river is still covered with blue and white zigzags, to represent water;

some of

the fighting groups are yet perfect; and two very beautiful royal

chariots, one

of which is surmounted by a richly ornamented parasol-canopy, are as

fresh and

brilliant as ever. The

horses

throughout are excellent. The chariot frieze is almost

Panathenaic in its effect of multitudinous movement; while the horses

in the

camp of Rameses, for naturalness and variety of treatment, are perhaps

the best

that Egyptian art has to show. It is worth noting also that a horsemen,

that rara avis,

occurs

some four or five times

in different parts of the picture. The

scene

of the campaign is laid in Syria. The river of blue and white

zigzags is the Orontes;10 the

city of the besieged is

Kadesh or

Kades;11 the

enemy are the Kheta. The whole is, in fact, a

grand

picture-epic of the events immortalised in the poem of Pentaur

–

that poem

which M. de Rougé has described as “a sort of

Egyptian

Iliad.” The comparison

would, however, apply to the picture with greater force than it applies

to the

poem. Pentaur, who was in the first place a courtier and in the second

place a

poet, has sacrificed everything to the prominence of his central

figure. He is

intent upon the glorification of the King; and his poem, which is a

mere pæan

of praise, begins and ends with the prowess of Rameses Mer-Amen. If,

then, it

is to be called an Iliad, it is an Iliad from which everything that

does not

immediately concern Achilles is left out. The picture, on the contrary,

though

it shows the hero in combat and in triumph, and always of colossal

proportions,

yet has space for a host of minor characters. The episodes in which

these

characters appear are essentially Homeric. The spy is surprised and

slain, as

Dolon was slain by Ulysses. The men feast, and fight, and are wounded,

just

like the long-haired sons of Achaia; while their horses, loosed from

the yoke,

eat white barley and oats “Hard

by their chariots, waiting for the dawn.”

Like

Homer, too, the artist of the battle-piece is careful to point out

the distinguishing traits of the various combatants. The Kheta go three

in a

chariot; the Egyptians only two. The Kheta wear a moustache and

scalplock; the

Egyptians pride themselves on “a clean shave,” and

cover

their bare heads with

ponderous wigs. The Sardinian contingent cultivate their own thick

hair,

whiskers, and mustachios; and their features are distinctly European.

They also

wear the curious helmet, surmounted by a ball and two spikes, by which

they may

always be recognised in the sculptures. These Sardinians appear only in

the

border-frieze, next the floor. The sand had drifted up just at that

point, and

only the top of one fantastic helmet was visible above the surface. Not

knowing

in the least to what this might belong, we set the men to scrape away

the sand;

and so, quite by accident, uncovered the most curious and interesting

group in

the whole picture. The Sardinians12

(in Egyptian Shardana)

seem to

have been naturalised prisoners of war drafted into the ranks of the

Egyptian

army; and are the first European people whose name appears on the

monuments. There is

but one hour in the twenty-four at which it is possible to form

any idea of the general effect of this vast subject; and that is at

sunrise.

Then only does the pure day stream in through the doorway, and temper

the gloom

of the side-aisles with light reflected from the sunlit floor. The

broad

divisions of the picture and the distribution of the masses may then be

dimly

seen. The details, however, require candle-light, and can only be

studied a few

inches at a time. Even so, it is difficult to make out the upper groups

without

the help of a ladder. Salame, mounted on a chair and provided with two

long

sticks lashed together, could barely hold his little torch high enough

to

enable the Writer to copy the inscription on the middle tower of the

fortress

of Kadesh. It is

fine

to see the sunrise on the front of the Great Temple; but

something still finer takes place on certain mornings of the year, in

the very

heart of the mountain. As the sun comes up above the eastern hill-tops,

one

long, level beam strikes through the doorway, pierces the inner

darkness like

an arrow, penetrates to the sanctuary, and falls like fire from heaven

upon the

altar at the feet of the gods. No one

who

has watched for the coming of that shaft of sunlight can

doubt that it was a calculated effect, and that the excavation was

directed at

one especial angle in order to produce it. In this way Ra, to whom the

temple

was dedicated, may be said to have entered in daily, and by a direct

manifestation of his presence to have approved the sacrifices of his

worshippers. I need

scarcely say that we did not see half the wall-sculptures or even

half the chambers, that first afternoon at Abou Simbel. We rambled to

and fro,

lost in wonder, and content to wonder, like rustics at a fair. We had,

however,

ample time to come again and again, and learn it all by heart. The

Writer went

in constantly, and at all hours; but most frequently at the end of the

day’s

sketching, when the rest were walking or boating in the cool of the

late

afternoon. It is a

wonderful place to be alone in – a place in which the very

darkness and silence are old, and in which Time himself seems to have

fallen

asleep. Wandering to and fro among these sculptured halls, like a shade

among

shadows, one seems to have left the world behind; to have done with the

teachings of the present; to belong one’s self to the past.

The

very gods

assert their ancient influence over those who question them in

solitude. Seen

in the fast-deepening gloom of evening, they look instinct with

supernatural

life. There were times when I should scarcely have been surprised to

hear them

speak – to see them rise from their painted thrones and come

down

from the

walls. There were times when I felt I believed in them. There

was

something so weird and awful about the place, and it became so

much more weird and awful the farther one went in, that I rarely

ventured

beyond the first hall when quite alone. One afternoon, however, when it

was a

little earlier, and therefore a little lighter, than usual, I went to

the very

end, and sat at the feet of the gods in the sanctuary. All at once (I

cannot

tell why, for my thoughts just then were far away) it flashed upon me

that a

whole mountain hung – ready, perhaps, to cave in –

above my

head. Seized by a

sudden panic such as one feels in dreams, I tried to run; but my feet

dragged,

and the floor seemed to sink under them. I felt I could not have called

for

help, though it had been to save my life. It is unnecessary, perhaps,

to add

that the mountain did not cave in, and that I had my fright for

nothing. It

would have been a grand way of dying, all the same; and a still grander

way of

being buried. My

visits

to the great temple were not always so dramatic. I sometimes

took Salame, who smoked cigarettes when not on active duty, or held a

candle

while I sketched patterns of cornices, head-dresses of kings and gods,

designs

of necklaces and bracelets, heads of captives, and the like. Sometimes

we

explored the side-chambers. Of these there are eight; pitch-dark, and

excavated

at all kinds of angles. Two or three are surrounded by stone benches

cut in the

rock; and in one the hieroglyphic inscriptions are part cut, part

sketched in

black and left unfinished. As this temple is entirely the work of

Rameses II,

and betrays no sign of having been added to by any of his successors,

these

evidences of incompleteness would seem to show that the king died

before the

work was ended. I was

always under the impression that there were secret places yet

undiscovered in these dark chambers, and Salame and I were always

looking for

them. At Denderah, at Edfû, at Medinet Habu, at

Philæ,13 there

have

been found crypts in the thickness of the walls and recesses under the

pavements, for the safe-keeping of treasure in time of danger. The

rock-cut

temples must also have had their hiding-places; and those would

doubtless take

the form of concealed cells in the walls, or under the floors, of the

side-chambers. To come

out from these black holes into the twilight of the great hall

and see the landscape set, as it were, in the ebon frame of the

doorway, was

alone worth the journey to Abou Simbel. The sun being at such times in

the

west, the river, the yellow sand-island, the palms and tamarisks

opposite, and

the mountains of the eastern desert, were all flooded with a glory of

light and

colour to which no pen or pencil could possibly do justice. Not even

the

mountains of Moab in Holman Hunt’s

“Scapegoat” were

so warm with rose and gold. Thus our

days passed at Abou Simbel; the workers working; the idlers

idling; the strangers from the outer world now and then coming and

going. The

heat on shore was great, especially in the sketching-tents; but the

north

breeze blew steadily every day from about an hour after sunrise till an

hour before

sunset, and on board the dahabeeyah it was always cool. The happy couple took advantage of this good wind to do a good deal of

boating, and by judiciously timing their excursions, contrived to use

the tail

of the day’s breeze for their trip out, and the strong arms

of

four good rowers

to bring them back again. In this way they managed to see the little

rock-cut

Temple of Ferayg, which the rest of us unfortunately missed. On another

occasion they paid a visit to a certain Sheykh who lived at a village

about two

miles south of Abou Simbel. He was a great man, as Nubian magnates go.

His name

was Hassan Ebn Rashwan el Kashef, and he was a grandson of that same

old Hassan

Kashef who was vice-regent of Nubia in the days of Burckhardt and

Belzoni. He

received our Happy Couple with distinguished hospitality, killed a

sheep in

their honour, and entertained them for more than three hours. The meal

consisted of an endless succession of dishes, all of which, like that

bugbear

of our childhood, the hated Air with Variations, went on repeating the

same

theme under a multitude of disguises; and, whether roast, boiled,

stewed or

minced, served on skewers, smothered in rice, or drowned in sour milk,

were

always mutton au fond.

We now

despaired of ever seeing a crocodile; and but for a trail that

our men discovered on the island opposite, we should almost have ceased

to

believe that there were crocodiles in Egypt. The marks were quite fresh

when we

went to look at them. The creature had been basking high and dry in the

sun,

and this was the point at which he had gone down again to the river.

The damp

sand at the water’s edge had taken the mould of his huge

fleshy

paws, and even

of the jointed armour of his tail, though this last impression was

somewhat

blurred by the final rush with which he had taken to the water. I doubt

if

Robinson Crusoe, when he saw the famous footprint on the shore, was

more

excited than we of the Philæ at sight of this genuine and

undeniable trail. As for

the idle man, he flew at once to arms and made ready for the

fray. He caused a shallow grave to be dug for himself a few yards from

the

spot; then went and lay in it for hours together, morning after

morning, under

the full blaze of the sun, – flat, patient, alert,

– with

his gun ready cocked,

and a Pall Mall Budget up his back. It was not his fault if he narrowly

escaped

sunstroke, and had his labour for his reward. That crocodile was too

clever for

him, and took good care never to come back. Our

sailors, meanwhile, though well pleased with an occasional holiday,

began to find About Simbel monotonous. As long as the Bagstones stayed,

the two

crews met every evening to smoke, and dance, and sing their quaint

roundelays

together. But when rumours came of wonderful things already done this

winter

above Wady Halfeh – rumours that represented the Second

Cataract

as a populous

solitude of crocodiles – then our faithful consort slipped

away

one morning

before sunrise, and the Philæ was left companionless. At this

juncture, seeing that the men’s time hung heavy on their

hands,

our painter conceived the idea of setting them to clean the face of the

northernmost Colossus, still disfigured by the plaster left on it when

the

great cast14 was

taken by Mr. Hay more than half a century

before.

This happy thought was promptly carried into effect. A scaffolding of

spars and

oars was at once improvised, and the men, delighted as children at

play, were

soon swarming all over the huge head, just as the carvers may have

swarmed over

it in the days when Rameses was king. All they

had to do was to remove any small lumps that might yet adhere

to the surface, and then tint the white patches with coffee. This they

did with

bits of sponge tied to the ends of sticks; but Reïs Hassan, as

a

mark of

dignity, had one of the painter’s old brushes, of which he

was

immensely proud. It took

them three afternoons to complete the job; and we were all sorry

when it came to an end. To see Reïs Hassan artistically

touching

up a gigantic

nose almost as long as himself; Riskalli and the cook-boy staggering to

and fro

with relays of coffee, brewed “thick and slab” for

the

purpose; Salame perched

cross-legged, like some complacent imp, on the towering rim of the

great

pschent overhead; the rest chattering and skipping about the

scaffolding like monkeys,

was, I will venture to say, a sight more comic than has ever been seen

at Abou

Simbel before or since. Rameses’

appetite for coffee was prodigious. He consumed I know not how

many gallons a day. Our cook stood aghast at the demand made upon his

stores.

Never before had he been called upon to provide for a guest whose mouth

measured three feet and a half in width. Still,

the

result justified the expenditure. The coffee proved a capital

match for the sandstone; and though it was not possible wholly to

restore the

uniformity of the original surface, we at least succeeded in

obliterating those

ghastly splotches, which for so many years have marred this beautiful

face as

with the unsightliness of leprosy. What

with

boating, fishing, lying in wait for crocodiles, cleaning the

colossus, and filling reams of thin letter paper to friends at home, we

got

through the first week quickly enough – the painter and the writer working

hard, meanwhile, in their respective ways; the painter on his big

canvas in

front of the temple; the writer shifting her little tent as she listed.

Now,

although the most delightful occupation in life is undoubtedly

sketching, it must be admitted that the sketcher at Abou Simbel works

under

difficulties. Foremost among these comes the difficulty of position.

The great temple stands within about twenty-five yards of the brink of the bank,

and the

lesser temple within as many feet; so that to get far enough from

one’s subject

is simply impossible. The present writer sketched the small temple from

the

deck of the dahabeeyah; there being no point of view obtainable on

shore. Next

comes

the difficulty of colour. Everything, except the sky and the

river, is yellow – yellow, that is to say, “with a

difference; “ yellow ranging

through every gradation of orange, maize, apricot, gold, and buff. The

mountains are sandstone; the temples are sandstone; the sandslope is

powdered

sandstone from the sandstone desert. In all these objects, the scale of

colour

is necessarily the same. Even the shadows, glowing with reflected

light, give

back tempered repetitions of the dominant hue. Hence it follows that he

who

strives, however humbly, to reproduce the facts of the scene before

him, is

compelled, bon gré, mal

gré,

to

execute what some our young painters would now-a-days call a Symphony

in

Yellow. Lastly,

there are the minor inconveniences of sun, sand, wind, and

flies. The whole place radiates heat, and seems almost to radiate

light. The

glare from above and the glare from below are alike intolerable.

Dazzled,

blinded, unable to even look at his subject without the aid of

smoke-coloured

glasses, the sketcher whose tent is pitched upon the sandslope over

against the

great Temple enjoys a foretaste of cremation. When the

wind blows from the north (which at this time of the year is

almost always) the heat is perhaps less distressing, but the sand is

maddening.

It fills your hair, your eyes, your water-bottles; silts up your

colour-box;

dries into your skies; and reduces your Chinese white to a gritty paste

the

colour of salad-dressing. As for the flies, they have a morbid appetite

for

water-colours. They follow your wet brush along the paper, leave their

legs in

the yellow ochre, and plunge with avidity into every little pool of

cobalt as

it is mixed ready for use. Nothing disagrees with them; nothing poisons

them –

not even olive-green. It was a delightful time, however – delightful alike for those who worked and those who rested – and these small troubles counted for nothing in the scale. Yet it was pleasant, all the same, to break away for a day or two, and be off to Wady Halfeh. ____________________________1 The late

Vicomte E. de Rougé, in a letter to M. Guigniaut on the

discoveries at Tanis,

believes that he detects the Semitic type in the portraits of Rameses

II and

Seti I; and even conjectures that the Pharaohs of the nineteenth dynasty may

have

descended from Hyksos ancestors: “L’origine de la

famille

des Ramsés nous est

jusqu’ ici complétement inconnue: sa

prédilection

pour le dieu Set

ou Sutech,

qui éclate dès l’abord par le nom de

Séti

Iere (Sethos),

ainsi

que d’autres indices, pouvaient déjà

engager

à la reporter vers la Basse Egypte. Nous savions

même que

Ramsés II avait

épousé une fille du prince de Khet, quand le

traité de l’an 22 eut ramené la

paix entre les deux pays. Le profil

très-décidément sémitique

de Séti et

de

Ramsés se distinguait nettement des figures ordinaires de

nos

Pharaons

Thébains.” (See "Revue

Archéologique,"

vol. ix. A.D. 1864.) In the course of the same letter, M. de

Rougé adverts to

the magnificent restoration of the temple of Sutech at Tanis (Sān) by

Rameses

II, and to the curious fact that the god is there represented with the

peculiar

head-dress worn elsewhere by the Prince of Kheta. It is to

be remembered, however, that the patron deity of Rameses II was

Amen-Ra. His homage of Sutech (which might possibly have been a

concession to

his Khetan wife) seems to have been confined almost exclusively to

Tanis, where

Ma-at-iri-neferu-Ra may be supposed to have resided. 2 “L’absence de

points fouillés,

la simplification

voulue, la restriction des détails et des ornements

à

quelques sillons plus ou

moins hardis, l’engorgement de toutes les parties

délicates, démontrent que les

Egyptiens étaient loin d’avoir des

procédés

et des facilités inconnus.” – "La Sculpture Egyptienne",

par

Emile Soldi,

p. 48. “Un

fait qui nous parait avoir dû entraver les progrès

de la

sculpture,

c’est l’habitude probable des sculpteurs ou

entrepreneurs

égyptiens

d’entreprendre le travail à même sur la

pierre, sans

avoir préalablement

cherché le modèle en terre glaise, comme on le

fait de

nos jours. Une fois le

modèle fini, on le moule et on le reproduit mathematiquement

définitive. Ce

procédé a toujours été

employé dans

les grandes époques de l’art; et il ne nous

a pas semblé qu’il ait jamais

été en usage

en Egypte.” – Ibid.

p. 82. M. Soldi

is also of opinion that the Egyptian sculptors were ignorant of

many of the most useful tools known to the Greek, Roman, and modern

sculptors,

such as the emery-tube, the diamond-point, etc. etc. 3 On the

left

leg of this colossus is the famous Greek inscription discovered by

Messrs.

Bankes and Salt. It dates from the reign of Psammetichus I, and

purports to

have been cut by a certain Damearchon, one of the 240,000 Egyptian

troops of

whom it is related by Herodotus (Book ii. chaps. 29, 30) that they

deserted

because they were kept in garrison at Syene for three years without

being

relieved. The inscription, as translated by Colonel Leake, is thus

given in

Rawlinson’s "Herodotus"

(vol. ii.

p. 37): “King Psamatichus having come to Elephantine, those

who

were with

Psamatichus, the son of Theocles wrote this. They sailed, and came to

above

Kerkis, to where the river rises . . . the Egyptian Amasis. . . . The

writer is

Damearchon the son of Amœbichus, and Pelephus (Pelekos), the

son

of Udamus.”

The king Psamatichus here named has been identified with the Psamtik I

of the

inscriptions. It was in his reign, and not as it has sometimes been

supposed,

in the reign of Psammetichus II, that the great military defection took

place. 4 Ra, the

principal solar

divinity, generally represented with the head of a hawk, and the

sun-disk on

his head. “Ra

veut dire faire, disposer; c’est,

en effet, le dieu

Ra qui a disposé, organisé le monde, dont la

matière lui a été donnée

par Ptah.”

– P. Pierret: "Dictionnaire

d’Archéologie

Egyptienne."

“Ra

est une autre des intelligences démiurgiques. Ptah avait

créé le

soleil; le soleil, a son tour, est le

créateur des êtres, animaux et hommes.

Il est

à l’hémisphère

supérieure ce qu’Osiris est à

l’hémisphère inférieure. Ra

s’incarne

à

Héliopolis.” – A. Mariette: "Notice des

Monuments à Boulak,"

p. 123. 5 An

instance occurs, however, in a small inscription sculptured on the

rocks of the

Island of Sehayl in the first cataract, which records the second

panegyry of

the reign of Rameses II. – See "Récueil des

Monuments,

etc.:" Brugsch, vol. ii., Planche lxxxii.,

Inscription No.

6. 7 It is

not

often that one can say of a female head in an Egyptian wall-painting

that it is

beautiful; but in these portraits of the Queen, many times repeated

upon the

walls of the first Hall of the Temple of Hathor, there is, if not

positive

beauty according to our western notions, much sweetness and much grace.

The

name of Nefertari means Perfect, Good, or Beautiful Companion. That the

word

“Nefer” should mean both Good and Beautiful

– in

fact, that Beauty and Goodness

should be synonymous terms – is not merely interesting as it

indicates a lofty

philosophical standpoint, but as it reveals, perhaps, the latent germ

of that

doctrine which was hereafter to be taught with such brilliant results

in the

Alexandrian Schools. It is remarkable that the word for Truth and

Justice (Ma)

was also

one and the same. There is

often a quaint significance about Egyptian proper names which

reminds one of the names that came into favour in England under the

Commonwealth. Take for instance Bak-en-Khonsu,

Servant-of-Khons; Pa-ta-amen,

the

Gift of Ammon; Renpitnefer,

Good-year; Nub-en Tekh,

Worth-her-Weight-in-Gold (both women’s names); and Hor-mes-out’-a-Shu,

Horus-son-of-the-Eye-of-Shu – which

last, as a tolerably long compound, may claim relationship with

Praise-God

Barebones, Hew-Agag-in Pieces-before-the-Lord, etc. etc. 8 Ra

Harmachis, in Egyptian Har-em-Khou-ti, personifies the sun rising upon

the

eastern horizon. 9 See

chap. viii, pp. 126; also chap. xxi. 10 In

Egyptian, Aaranatu.

11 In

Egyptian, Kateshu.

“Aujourdhui

encore il existe une ville de Kades près d’une

courbe de

l’Oronte dans le

voisinage de Homs.” Leçons

de M. de Rougé,

Professées au Collége de France.

See

"Melanges D’Archeologie," Egyp.

and Assyr., vol. ii. p 269. Also a valuable paper, entitled

“The

Campaign of

Rameses II against Kadesh,” by the Rev. G. H. Tomkins, "Trans. of the Soc. of

Bib. Arch."

vol.

viii. part 3, 1882. The bend of the river is actually given in the

bas-reliefs. 12 “La

légion S’ardana

de

l’armée de Ramsés II

provenait d’une première descente de ces peuples

en

Egypte. ‘Les S’ardaina

qui étaient des prisonniers de

sa majesté,’ dit expressément le texte

de Karnak,

au commencement du poëme de Pentaur.

Les archéologues ont remarqué la

richesse de leur costume et de leurs armures. Les principales

pièces de leur

vêtements semblent couvertes de broderies. Leur bouchier est

une

rondache: ils

portent une longue et large épée de forme

ordinaire, mais

on remarque aussi

dans leurs mains une épée d’une

longueur

démesurée. Le casque des S’ardana est

très caracterisque; sa forme est arrondie, mais il est

surmonté d’une tige qui

supporte une boule de métal. Cet ornament est

accompagné

de deux cornes en

forme de croissant. . . . Les S’ardana de

l’armée

Egyptienne ont seulement des

favoris et des moustaches coupés très

courts.”

– "Memoire sur les Attaques

Dirigées contre l’Egypte,"

etc. etc.

E. de Rougé. "Revue

Archéologique,"

vol. xvi. pp. 90, 91. 13 A rich

treasure of gold and silver rings was found by Ferlini, in 1834,

immured in the

wall of one of the pyramids of Meröe, in Upper Nubia. See Lepsius’s

Letters,

translated by L. and J.

Horner, Bohn, 1853, p. 151. 14 This cast, the property of the British Museum, is placed over a door leading to the library at the end of the northern Vestibule, opposite the staircase. I was informed by the late Mr. Bonomi that the mould was made by Mr. Hay, who had with him an Italian assistant picked up in Cairo. They took with them some barrels of plaster and a couple of ladders, and contrived, with such spars and poles as belonged to the dahabeeyah, to erect a scaffolding and a matted shelter for the plasterman. The Colossus was at this time buried up to its chin in sand, which made their task so much the easier. When the mould of the head was brought to England, it was sent to Mr. Bonomi’s studio, together with a mould of the head of the Colossus at Mitrahenny, a mould of the apex of the fallen obelisk at Karnak, and moulds of the wall-sculptures at Bayt-el-Welly. Mr. Bonomi superintended the casting and placing of all these in the Museum about three years after the moulds were made. This was at the time when Mr. Hawkins held the post of Keeper of Antiquities. I mention these details, not simply because they have a special interest for all who are acquainted with Abou Simbel, but because a good deal of misapprehension has prevailed on the subject, some travellers attributing the disfigurement of the head to Lepsius, others to the Crystal Palace Company, and so forth. Even so careful a writer as the late Miss Martineau ascribes it, on hearsay, to Champollion. |