| THE

GARDEN

THE

garden is the touch

of nature which mediates between the seclusion of the home and the

publicity of the street. It is nature controlled by art. In this

assembling of trees, shrubbery, vines and flowers about the home, in

this massing of greensward or beds of bloom, man is conjuring the

beauties of nature into being at his very doorstep, and compelling

them to refresh his soul with an ever-changing pageantry of life and

color.

Unfortunately,

in this

workaday world, the possibility of the householder to be also a

gardener is regulated by severe necessity. As men crowd together, the

value of land increases, and so it is that in the heart of a large

city only an enlightened public sentiment makes practicable the

setting apart of areas where all may enjoy the redeeming grace of

foliage and flowers. In proportion to the scattering of men is the

extension of the garden possible, until the limit is reached in the

lodge amid the wilderness, where the overpowering presence of nature

makes the intrusion of an artificial garden an impertinence. In the

village, then, the opportunities of the garden seem to be greatest.

But

even the city home need not be wholly without the purifying influence

of plants and flowers. Where houses are most congested and there is

no land about the walls, one may resort to potted plants, and the

streets may be decorated with palms or small trees in tubs or big

terra-cotta pots. Vines may be planted in long wooden boxes, or,

better still, in cement troughs against the sides of the

house.

If one objects to

growing flowers in the rooms, little balconies or railed-in brackets

may be built outside the windows for holding rows of potted plants.

Hanging baskets containing vines or ferns are most effective on

porches, while boxes of earth may stand upon upper balconies from

which vines may grow and trail over the outer walls. A movement for

the decoration, with geraniums and other plants and vines, of the

residence district of the poor, would, I firmly believe, yield

immediate returns in the advancement of culture.

Another

expedient in the

absence of land about the home is the roof garden. If this were

sheltered from the prevailing wind with a wall or screen of glass, it

would give the urbanite a miniature park where be could enjoy fresh

air in seclusion.

But

these devices are all makeshifts for the unfortunate ones who must

live in the heart of a city. When a home is built in the town or

country, the matter of a garden must be taken into consideration.

Indeed, this should be studied even before the house is located on

the land. Modern town lots are commonly cut up in long, narrow

strips, so that by putting the house in the midst of a lot there will

be a front and a back yard. This conventional arrangement has its

advantages, although, as a rule, an unnecessary amount of space is

wasted on the back yard, the chief utility of which seems . to be to

afford room for the garbage barrel and for drying clothes. If a hint

is taken from the compact method of clothes-drying practiced by the

Chinese at their laundries, the land so often set apart for this

purpose can be greatly restricted, thus correspondingly enlarging the

garden. Two alternatives then remain to place the house far back

on the lot and have the garden all at the front, or to bring the

house forward and have a small open plot in front and a retired

garden in the rear.

Upon

hillsides, if the streets are laid out in a rational manner to

conform with the contour of the land, winding naturally up the

slopes, the lots will of necessity be cut into all sorts of irregular

shapes. This gives endless latitude in the placing of the houses upon

the lots, so that unconventional

groups of

buildings may be set upon the landscape in the most picturesque

fashion. But even when the lots are of the usual rectangular shape,

much ingenuity may be exercised in the location of the house with

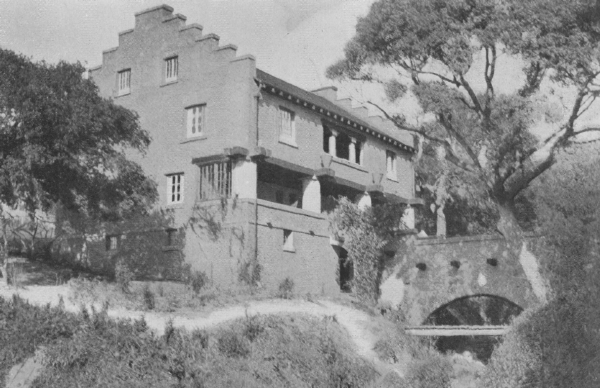

reference to the garden. I have in mind one corner lot with a stream

winding through it, shaded with venerable live-oaks. By putting the

rear of the house on the property line of the side street, the front

wall was close to the bank of the stream, and was approached by a

simple brick bridge which led to the broad veranda about the

entrance. This unusual location gave the effect of a large front

garden, and made the stream the principal feature. A more

conventional arrangement would have relegated this charming little

watercourse to the back yard.

Brick

Home in Dutch Style Approached Over a Bridge

Whenever

an entire block

of homes can be studied in one plan, much more can be accomplished

than by the customary method of each man for himself, regardless of

the interests of his neighbors. For example, if the houses must be

crowded together on lots of fifty-feet width, the garden space could

be made to yield the utmost privacy by some such arrangement as the

following: Suppose the houses to be set two or three feet back from

the property line, leaving just room enough to plant vines and bright

flowers along the front. If, then, a brick fire wall were erected on

each fifty-foot division line, the houses could be built touching one

another, and thus completely filling the block, save for the margin

of flowers. By planning each house on three sides of a hollow square,

with long, narrow rooms in wings extending lengthwise on the lots,

each home would have an inner court, completely sheltered from

neighbors, and with ample space behind it for a back yard. Or this

scheme might be reversed by facing the hollow square to the street,

in which case the court might be sheltered by a hedge or low wall.

According to the former plan, the long front wall would perhaps

appear somewhat monotonous, but it could be diversified by having

generous passageways opening directly through the houses into the

courts, and by the judicious use of open timber work and carving, if

the houses were of wood, or of ornamental terra-cotta, if of brick.

The continuous line of varied bloom next the sidewalk, with shade

trees on the street, would relieve this scheme of any stiffness. I

mention these devices merely to show that many interesting garden

effects might be obtained by the exercise of more thought in the

placing of the house, and especially by studying a group of

structures in connection with their surrounding land.

Now,

as to the garden itself: In the matter of architecture, two leading

types appear to be in vogue in California, a northern and a southern,

differentiated by an extreme or slight roof pitch. In considering the

garden, two pronounced types are also encountered the natural and

formal each of which is subject to two modes of treatment

according to the character of vegetation used, whether this be

predominantly indigenous or predominantly exotic.

By a

natural garden I understand one that simulates, as nearly as may be,

the charm of the wilderness, tamed and diversified for convenience

and accessibility. A treatment of this sort demands very considerable

stretches of land to produce a satisfactory result. The English parks

are probably the finest examples of this type, which can hardly be

successfully applied to town lots not over a hundred feet in width at

most. In a district where the lots are happily laid out on a somewhat

more generous plan, and especially where nature has not been already

despoiled of all her charms, this form of garden may be developed to

best advantage. If situated in the California Coast region, within

the redwood belt, nothing could give greater sense of peace and charm

than a grove of these noble trees varied with liveoaks, and with

other native trees and shrubs growing in their shade, such as madroρo

and manzanita, sweet-scented shrub, wild currant, redbud and azalea,

with wild-flowers peering from the leafy covert the hound's

tongue, baby-blue-eyes, shooting-star, fritillaria, eschscholtzia,

and a host of others. About such a garden as this there is a purer

sentiment a more refined love of nature undefiled, than can be

obtained by more artificial means; but such a garden needs room. Big

trees, and especially such native evergreens as the redwood and

live-oak, take an unexpected amount of space, and if crowded together

make the surroundings too dark and gloomy. On the California Coast

there is need of all the sunlight that heaven bestows. Then, too,

many people build their homes on the hillsides to enjoy the view. If

numbers of large trees are set out about their homes, the outlook is

soon obliterated, and the charm of far sweeps of bay and purple

ranges is lost. It may be suggested that there are plenty of smaller

native trees and shrubs that can be used, which will be adapted to a

restricted plot of ground. Practically it will be found, it seems to

me, that a garden thus limited to indigenous plants will prove rather

dull in color and lacking in character. Without the woodsy effect of

light and shadow, or the brilliance of cultivated flowers, the little

patch of green will be apt to seem rather commonplace.

This

brings me to the second treatment of the natural type of garden

the introduction of exotic plants into the scheme. The coast of

California, as far north as the San Francisco Bay region, and the

interior valleys for a hundred miles and more farther to the

northward, have a climate of such temperateness that an extraordinary

variety of exotics will thrive which, in less favored regions, would

only live under glass. Bamboo, palms, dracaenas, magnolias, oranges,

bananas, and innumerable other fragrant or showy plants of New

Zealand and Australia, of Africa, South America and the Indies, grow

with the hardihood of natives. Among the trees most commonly

introduced are such as the eucalypti, acacias, pittosporums,

grevilias, and araucarias, but the number of successfully growing

exotics is bewildering.

Flowers

which in colder climates must be carefully tended in pots, grow here

like rank weeds, while vines that in more rugged localities develop a

few timid sprays, shoot up here like Jack's beanstalk. An entire

house may be embowered in a single rose vine. Geranium hedges may

grow to a height of eight feet or more. It is a common sight to see

hundreds of feet of stone wall so packed with the pink blossoms of

the ivy-geranium that it appears like a continuous mass of bloom. The

calla sends up its broad leaves and white cups as high as a man's

head. The lemon verbena grows into a tree.

In the

old-fashioned

California gardens, advantage was taken of this prodigal growth, but

without much study of arrangement. They were natural gardens of

exotics, with curved paths, violet bordered, winding through the

shrubbery. Often there was great incongruity in the assembling of

plant forms, and the charm lay in the individual plants rather than

in the ensemble.

Over

against the natural garden, whether of indigenous or exotic plants,

may be set by way of contrast, the formal garden. The Italians are

masters of this type of garden architecture, and it is to them that

Californians may well turn for inspiration. A formal garden is one

arranged according to an architectural plan, with terraces, pools,

fountains and watercourses, out-of-door rooms, and some suggestions

of architectural or sculptural adornment. It would be possible to

design a formal garden exclusively or mainly of indigenous plants,

but this would unnecessarily cramp the artist in his work. By having

a choice of all the plants of the temperate zone, the landscape

gardener is given limitless power of expression in his art. It is, of

course, a prime essential to consider the effects of massing and

grouping, the juxtaposition of plants that seem to belong together,

and a due regard for harmony in color scheme.

Another

type which may be studied by the Californians to great advantage is

the Japanese garden. Conventional to a degree with which the Western

mind cannot be expected to sympathize, it is, nevertheless, a

miniature copy of nature made with that consummate aesthetic taste

characteristic of the Japanese race. The garden as they conceive it

must have its mimic mountains and lakes, its rivulets spanned by

arching bridges, its special trees and stones, all prescribed and

named according to certain stereotyped plans. But despite all this

conservatism and conventionality, the details are free and graceful,

with a completeness and

subtlety of finish that makes the Western

garden

seem crude and

commonplace by comparison. Their carved gates, patterned bamboo

fences, stone lanterns, thatched summer houses, and other ornamental

accessories are original and graceful in every detail. Like the

Italians, the Japanese make use of retired nooks and out-of-door

rooms, while artificial watercourses are features of their gardens.

My

desire in calling especial attention to these two types of gardens

developed by races as widely sundered as the Italian and the

Japanese, is not that we in California should imitate either, or make

a vulgar mixture of the two, but, rather, by a careful study of both,

to select those features which can be best adapted to our own life

and landscape, so that a new and distinctive type of garden may be

evolved here, based upon the best examples of foreign lands. As to

the precise form which this new garden type of California should

assume, it is perhaps premature to say, but one thing is vital, that

at least a portion of the space should be sequestered from public

view, forming a room walled in with growing things and yet giving

free access to light and air. To accomplish this there must be hedges

or vine-covered walls or trellises, with rustic benches and tables to

make the garden habitable. If two or more of these bowers are

planned, connected by sheltered paths, a center of interest for the

development of the garden scheme will be at once available. My own

preference for a garden for the simple home is a compromise between

the natural and formal types a compromise in which the carefully

studied plan is concealed by a touch of careless grace that makes it

appear as if nature had unconsciously made bowers and paths and

sheltering hedges.

In the

selection of plants there is one point which may be well kept in mind

to strive for a mass of bloom at all periods of the year. A

little study of the seasons at which various species flower will

enable one to have his garden a constant carnival of gay color. As

the China lilies and snowdrops wane in midwinter, the iris puts forth

its royal purple blossoms, followed by the tulips, the cannas, the geraniums

and the roses (both

of which latter are seldom entirely devoid of blossoms). In midsummer

there are eschscholtzias, poppies, hollyhocks, sweet peas and

marigolds, while chrysanthemums bloom in the autumn and early winter.

These are but the slightest hints of the way in which a study of the

floral procession of the seasons makes it possible to keep the garden

aglow with color at all seasons of the year.

In the

Japanese Garden at Golden Gate Park

Let

us, then, by all means, make the most of our gardens, studying them

as an art, the extension of architecture into the domain of life

and light. Let us have gardens wherein we can assemble for play or

where we may sit in seclusion at work; gardens that will exhilarate

our souls by the harmony and glory of pure and brilliant color, that

will nourish our fancy with suggestions of romance as we sit in the

shadow of the palm and listen to the whisper of rustling bamboo;

gardens that will bring nature to our homes and chasten our lives by

contact with the purity of the great Earth Mother.

|