| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2009 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

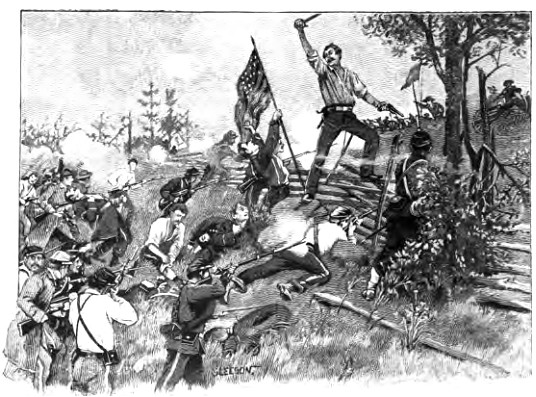

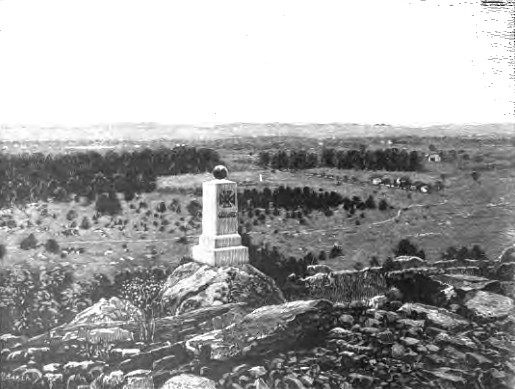

XIX. MAINE IN THE CIVIL WAR.

MAINE'S part in the Civil War was similar to that of many another state—she simply did her best. But that best was such an astonishing thing for a state of her resources, that the bare and cold statistics thrill her children's hearts with pride, and may well furnish excuse for a little boasting. She sent 72,945 men to the battlefields. The number killed in the army list (we have none of the navy or marine corps) amounted to 7,322. Maine furnished thirty-two infantry regiments, three regiments of cavalry, one regiment of heavy artillery, seven batteries of mounted artillery, seven companies of sharpshooters, thirty companies of unassigned infantry, seven companies of coast guards, and six companies for coast fortifications; 6,750 men were also contributed to the navy and marine corps. The amount of bounty paid in the state was $9,695,620.93. The value of hospital stores contributed was $731,134. Bangor boasted that she raised the first company of volunteers that enlisted in the United States. But the first company which filled its ranks and was accepted by the governor was the Lewiston Light Infantry. In the small town of Cherryfield the names of fifty volunteers were upon the enlistment roll in four hours after it was opened. Maine had an enrolled militia of about sixty thousand men, but in the "piping times of peace" there had been no drilling, and the militia was unarmed and unorganized. And yet the first and second regiments sent from Maine were so thoroughly armed and equipped as to receive especial praise from the United States Secretary of War. The Second Maine had the fortune to grace battle's brunt on eleven hard-fought fields in the course of two years. In the battle of Bull Run, where the Union army was completely routed and forced to flee, the Second carried itself with an undaunted courage that reflected great credit upon the state. A letter written to friends at home says: "The bravery of our boys is the theme of every one. All fought well, so well that it would seem difficult to particularize, but the boys speak so warmly of the conduct of Lieutenant Gurnsey, Captain Sargent, Lieutenant Casey, and Peter Welch, that I know it will give no offense to others to name them. Of young Gurnsey the boys say he is 'a little brick.' The regiment charged up a hill on a twenty-gun battery. At the top of the hill was a Virginia fence, only a few paces from the battery. Gurnsey commanded the left wing of his company, and, with a revolver in one hand and his sword in the other, he charged up the hill to the fence, on the top of which he leaped and, waving his sword, cried to his boys to follow him. Twice he led his men to the fence, but the murderous fire caused them to fall back and throw themselves on the ground behind an eminence, to shield themselves from the storm of iron hail. It was by this battery that the Ellsworth Zouaves were cut up. I noticed that young Gurnsey's clothes were covered with blood. His right-hand man was shot by his side. 'Then,' said he, 'I was mad, and would have reached that battery had we not been ordered back.'  "Peter Welch, I am told, rushed in and took two prisoners and brought them off, then went back, under a terrible fire, and brought off some of our wounded. At one time, when the regiment was forced to retire after a charge, Colonel Jameson said to his men: Who will go with me to the rescue of the wounded?' Six brave fellows followed him into the very jaws of death. "Little can you imagine how our hearts swell to our brave boys for their heroic conduct in this fight." But the history of these brave deeds is only the history of hundreds of others. Volumes could be filled with heart-thrilling examples of individual heroism. "Maine in the War" has been written, and we, at least, know these examples partially. To particularize, in so limited a space as these "Stories of Maine" afford, is to be unjust. The aim is only to cite cases where Maine, thrown into the thickest of the fight, showed her mettle. The Fourth Maine did duty in almost all the great battles that were fought during its term of service. At Fair Oaks, Malvern Hill, and Williamsburg, it rendered especially efficient service, as well as at Chancellorsville, where its commander, Major General Berry, was killed. The Fifth was another fighting regiment, and proved its valor by taking more prisoners than it ever had men in its ranks,—an almost unprecedented record. At the close of the battle in which the Union forces won Williamsburg and Yorktown, the Seventh Maine was visited by General McClellan and complimented for its gallantry. "Soldiers of the Seventh Maine," he said, "I have come to thank you for your bravery and good conduct in the action of yesterday. On this battle plain you and your comrades arrested the progress of the advancing enemy, saved the army from a disgraceful defeat, and turned the tide of victory in our favor. You have deserved well of your country and of your state; and in their gratitude they will not forget to bestow upon you the thanks and praise so justly your due. Continue to show the conduct of yesterday, and the triumph of our cause will be speedy and sure. In recognition of your merit you shall hereafter bear the inscription 'Williamsburg' on your colors. Soldiers, my words are feeble, but from the bottom of my heart I thank you!" With the Third Maine Regiment, commanded by Colonel (afterward General) O. O. Howard, originated the brilliant and laughable Stovepipe Artillery. The regiment was encamped within sight of the enemy's lines, in Virginia. Some of the men took a piece of stovepipe from a church, mounted it upon wheels, and ran it up to the top 'of a hill. It was a sport that relieved a little the horrors of war to see the enemy open a furious cannonade upon the inoffensive stovepipe. The Third's fighting was as successful as its fooling. After a hard-fought battle, when the regiment was reduced to one hundred and ninety-six rifles and fourteen officers, General Sickles said: "The little Third Maine saved the army to-day." The capture of Morris Island is said to have been largely due to the daring and skill of the Ninth Maine Regiment, and the finely drilled Eleventh had the honor of having been the first to pass and the last to leave the Chickahominy. The Fifteenth was the Aroostook regiment, and the men were forced to show their hardihood in the perils of the Mississippi swamps. In one year it lost three hundred and twenty-nine of its number, without being engaged in a battle. It had many of the hardships and sufferings without any of the glory of war, but its men showed the patient endurance which is sometimes the highest heroism. The Twelfth Maine distinguished itself by the capture of two batteries of six thirty-two pounders, with a stand of colors, a great quantity of ordnance stores, and Confederate currency to the amount of eight thousand dollars. The War Department ordered the captured colors to be retained by the regiment as a trophy of its brilliant victory. The heroism of the Maine soldiers in the minor battles of the war has naturally been less widely published. At the battle of Brandy Station the First Maine Cavalry made for itself a glorious record. The cavalry had not been highly esteemed, but on that day it saved the brigade under Kilpatrick, and when the fight was done received his hearty thanks for its services. Brandy Station is on the Orange and Alexandria Railroad, which crosses the Rappahannock River about fifty miles southwest of Washington. It is a small place, about five miles from the river, and near Culpeper. A fine, old-fashioned mansion, half a mile from the station, was the headquarters of the rebel general Stuart. In front of the house was a beautiful lawn, and behind it was woodland. A heavy force of artillery, cavalry, and infantry, upon the sloping grounds, faced the daring riders. They pressed up the hill and along its brow, an irresistible force that drove the enemy before it, Dashed at the battery, and captured it, cutting down such of the gunners as remained. It was the first battle of the regiment, and the men were wild with excitement and flushed with success. A mistake was made, here, in not carrying off the battery; but Colonel Douty planted a Union flag at the guns, and urged his men forward upon the enemy, leaving the guns unmanned. As

the Union men rushed after the retreating foe, from the woods on the

other side of the upland came other Confederate troops that seized

upon the guns, and when Colonel Douty turned from the enemy's

scattered and flying forces, he saw another detachment of them

manning the guns and apparently mustering in strong force to hold the

field.

The bugle rang out again the signal to charge, and as they rode back they saw the wide, sloping plain filled with fleeing Union troops and hotly pursuing Confederates. A steady, deadly fire was pouring from the guns, and mingled with the thunder of the artillery, with the rattle and the roar, was the wild, piteous cry of the horses as their flesh was torn by the bullets. There were shouts of combat and shrieks of the wounded and dying. And between these dreadful sounds came the tread of the horses of the flying cavalry—flying as if the day were lost. Again the bugle rang out, and again the battery was charged,—a deed of desperate courage. The "History of the First Maine Cavalry" thus records it: "The last charge brought them to a point in the valley between two hills, west of the battery and directly under its guns. At this critical moment it was discovered that they were completely surrounded and cut off from all support, while the Confederates were literally swarming on every side. The gunners on the hill were waiting to pour death through their devoted ranks. Lieutenant Colonel Smith was now in command, as Douty and some of the officers had been separated from the regiment during the hand-to-hand fight at the battery, and he saw only one avenue of escape. The men were formed and moved directly toward the battery as if inviting attack. For a moment they Dashed on, and when it was seen that the guns had been sighted and were about to be discharged, the order was given to swing to the right. In an instant after came the cannons' roar, but not a man or a horse fell. The grape and canister tore along the left flank, plowing the ground vacated but an instant before." At this moment of reprieve the glistening of bayonets was seen on the edge of the woods, and an orderly crossing the field was hailed with the question, "What are the troops in sight along the woods?" "The Sixth Maine," was his answer; and it was echoed along the ranks with a wild shout of joy. The danger was over since the Sixth Maine had come to the rescue. The Sixth, the lumbermen's regiment, was placed on record by its gallant colonel as a temperance regiment before it reached the field. As it passed through Philadelphia, a halt was made near some liquor shops. The proprietors were requested by the colonel not to sell liquors to his men, but they paid no attention whatever to the request. Colonel Knowles forthwith sent a squad of soldiers to shut up the shops, and placed a guard over the persistent rumsellers. He was immediately waited upon by a company of Quaker City fathers. "Friend Knowles," they said, "thy conduct meets our approval. We will back thee up if necessary." At Fredericksburg the Sixth made a noble record for itself. The supporting regiments on the right and left had broken under the terrific fire, and the enemy turned its attention to the Sixth Maine and the Fifth Wisconsin. Its entire fire was poured upon the ranks of the two regiments, and their destruction seemed imminent. But when they were expected to waver and break, there came, instead, a wild cheer, and a desperate rush upon the enemy's fortifications; and in four minutes from the time of attack the victory was won. The flag of the Sixth was the first to float from the enemy's battlements. The Tenth passed through great perils and hardships, being always in the thickest of the fight. In the valley of the Shenandoah it performed most notable service and showed great heroism. The men of the Thirteenth, Colonel Neal Dow's regiment, were among those that suffered the most severely and showed heroic fortitude. They endured first the almost tropical heat of Ship Island, and then were sent to Texas, where toilsome marches, malaria, and privations greatly reduced their ranks. Colonel Dow himself suffered the horrors of a Southern prison. Perhaps no Maine regiment endured more of the hardships of war, while receiving none of its emoluments, than did the Twenty-third. Most of the time of service was spent in guarding Washington. A fine company of men, socially and intellectually, they gave themselves to the severe labors of digging rifle pits and redoubts, of performing picket duty and building barricades. What the perils and hardships of war were may be understood from the records of the gallant Twenty-fourth. Nine hundred strong and able-bodied men enlisted, and but five hundred and seventy returned, and yet not one was killed in battle. This regiment served at the siege of Port Hudson. The Twenty-seventh, the York county regiment, showed its patriotism by remaining for the protection of Washington after its term of service had expired. The Twenty-eighth and Twenty-ninth regiments had their share in the fiercest battles of the war, as did also the Thirtieth, with an added share of terrible experience in the marsh lands of Louisiana. The Thirty-first plunged at once into the terrible battles of the Wilderness, and lost in one of the first engagements, in killed, wounded, and missing, two hundred and ninety-five men. The Maine Sixteenth had been left without proper clothing or camping outfit. The men had suffered incredible hardships from exposure to the cold, from hunger, and from a toilsome march, when they were plunged into the thickest of the terrible fight at Fredericksburg. They fought with desperate courage. Of four hundred and fifty men only two hundred and twenty-four survived the battle. "Whatever honor we can claim in that contest," said General Burnside, "was won by the Maine men."  The Twentieth won perhaps its greatest honors at Gettysburg, as did several other Maine regiments, and the Fifth Mounted Battery, which had before shown desperate courage in the bloodiest battles. The story of the battle has been told too often to warrant a repetition, but they were unfading laurels that the sons of Maine won that day. It was the Twentieth Maine that chanced to be in line when the Southern army, flying from the defeat of Richmond and Petersburg, found before them the alternative of surrender or utter annihilation. So Maine may boast as her share in the great Civil War that she raised the first company of volunteers, and that to her troops the surrender of the Confederate army was made,—but these were small things, indeed, in comparison with the years of heroic endeavor that came between. And for one story of bravery that is told a hundred remain untold; and greatest, often, was the heroism shown when the day was not won, and no one has had the heart to preserve the full details of the losing fight. |