| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2009 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

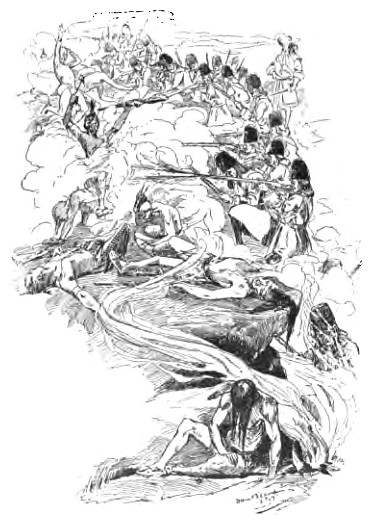

XIII. MAJOR WALDRON AND THE INDIANS.

THE province of Maine had now (1678) been purchased by Massachusetts, and, as the struggling settlers were still distressed by hostile Indians, the General Court of Massachusetts sent an army of a hundred and thirty English and forty friendly Indians to their relief. They came from Natick, and when they reached Dover they were incorporated with Major Waldron's troops. Major Waldron was a famous Indian-fighter, and had the reputation of being "one of the most perfidious and unscrupulous cheats in his treatment of the Indians." When they paid him what was due, he would fail to cross out their accounts, and exact payment again and again. In buying beaver skins by weight, he insulted and exasperated the Indians by insisting that his fist weighed just one pound. When their opportunity for revenge came, it was not likely that the savages would forget. But, in justice to the major, it must be said that in the first infamous treachery shown to the Indians in this campaign he was not the leader. He had sent a messenger to four hundred Indian warriors, inviting them to come to Dover to confer, in a friendly manner, upon a possible treaty of peace, pledging his honor for their safety. They came readily. Their own tribes were beginning to dwindle; the Massachusetts colony, growing strong, would send more and more soldiers to the aid of the Maine settlers. And they had always a lurking fear that the white man, with his many inventions, was the favorite child of the Great Spirit, and that, in spite of Squando and Simon and the other Indian seers, it was they, instead of the English, who were doomed to destruction. Peace was what the wiser among them really desired. But the burning and slaughtering of the Indians, and their merciless torturing of their captives, had been very recent, and were very fresh in the minds of the English, and ' they would have fallen upon them with furious slaughter if Major Waldron had not restrained them. He had pledged his sacred word that they should come and go in safety. The men made a dastardly plan, and although Major Waldron held out against it for a while, it is to be feared that his natural inclinations were with them from the first. Certain it is that he finally yielded, and one of the most infamous acts of treachery against the Indians of which the white settlers were ever guilty was perpetrated at this Dover conference. The Indians were invited by the English to engage with them in a sham battle. At a given signal there was to be a grand discharge of all the guns. The Indians guilelessly discharged their guns, while the English soldiers followed their secret instructions to load their muskets with balls and not to fire. Then they fell upon the helpless Indians, disarmed them all, and took them prisoners. Some of the Indians who were known to have been always friendly to the whites were set at liberty; but two hundred of the too confiding warriors were sent as prisoners to Boston. There all those convicted of taking life were executed, and he others were sent to the West Indies or other foreign countries and sold as slaves. Many colonists approved of this deed, and the government also sustained and abetted it.  The day after their sham-battle exploit, the troops under Major Waldron embarked in a vessel for Falmouth, and at Casco, whence the inhabitants had all been driven by the Indians, they established a garrison. Some of the settlers were emboldened by this protection to return to their homes, but the Indian attacks and depredations still continued. Seven men who ventured upon Munjoys Island, to kill some sheep that had been left there, were slain by the Indians, although they were armed and defended themselves desperately. In October the English returned to the Piscataqua, leaving about sixty men in the garrison. They had been gone but two days when a company of a hundred and twenty Indians, under the leadership of Mugg, a famous chief, made a furious attack upon the garrison. Mugg had been very friendly with the English and had lived some time among them. "He was the prime minister of the Penobscot sachem, an active and a shrewd leader, but who, by his intimacy with the English families, had worn off some of the ferocities of the savage character." Mugg called upon the inmates of the garrison to surrender, promising that they should be allowed to leave the place unharmed, with all their goods. Captain Henry Jocelyn, who commanded the fortress, unhesitatingly left it to confer with Mugg, placing himself completely in the power of the Indians. His confidence in Mugg was not misplaced, for no treachery whatever was practiced by the Indians. But a very curious thing happened. He returned unharmed to the fort, but only to find, to his great astonishment, that all the inmates, except those of his own household, had availed themselves of the Indians' permission to depart with their goods. They had hastily gathered together their household effects and taken to the boats, and were already at a good distance from shore. Jocelyn, who had not accepted the offered terms, finding himself thus abandoned and helpless, had no alternative but surrender. Mugg seems always to have dealt fairly in trade and in war, but not always to have been able to control his wily and treacherous allies. A naval expedition sent to Richmans Island for the rescue of some settlers who had taken refuge there, and for the removal of their property, was attacked by an Indian force that greatly outnumbered it. A part of the sailors were on board ship, and others on shore. The Indians immediately shot those on shore, or took them prisoners, and those on the vessel's deck were assailed by so furious a fire that they were forced to go below. Then the Indians cut the cables, and a strong wind blew the vessel ashore. The Indians shouted a threat to set the vessel on fire and burn the sailors to death unless they surrendered. Captain Fryer, the commander of the expedition, had been seriously wounded, and lay bleeding and helpless in the cabin. There were eleven in the vessel's hold, who agreed to surrender, upon condition that they should be allowed to ransom themselves within a given time by the payment of a certain amount of goods. The Indians accepted the terms, and released two of the prisoners, that they might obtain the ransom. They returned with the goods before the appointed time, but the Indians with whom they had made the terms had gone away. Other Indians had the remaining prisoners in charge, and they killed one of those who had returned with the ransom, took the goods, and refused to release the prisoners. The chieftain Mugg was very angry with the treacherous Indians. He was anxious for war to cease, and ventured to Piscataqua as an emissary of peace from Madockawando, his superior sagamore. Mugg carried with him to Piscataqua Captain Fryer, who was dying of his wounds, and restored him to his friends. He promised that the other prisoners should at once be set at liberty. Mugg was immediately given a passage to Boston, where, in behalf of Madockawando and another great chief, Cheberrind, he concluded a treaty. The treaty did not please all the Indians, which was not strange, for in it the English seem to have claimed everything and granted nothing. It was agreed that all hostilities should cease; that the English should receive full satisfaction for all damages they had suffered; that all prisoners and all vessels and goods which had been seized by the Indians should be restored; that the Indians should purchase ammunition only of agents appointed by the government; and that certain Indians accused of crime should be surrendered for trial and punishment. In concluding the treaty, Mugg said: "In attestation of my sincerity and honor, .I place myself a hostage in your hands till the captives, vessels, and goods are restored; and I lift my hand to heaven in witness of my honest heart in this treaty." Madockawando ratified this treaty, and fifty or sixty captives were restored to their homes. But the Canibas tribe, on the east bank of the Kennebec, remained hostile, scorned the treaty, and refused to release their captives. They were a powerful tribe, and were regarded by the English as very shrewd and sagacious. The site of their ancient village, opposite the mouth of Sandy River, is still shown. It is a fertile intervale, beautiful for situation. The ruins of their Roman Catholic chapel long remained, and its bell, weighing sixty-four pounds, was found in the ruins, and presented to Bowdoin College. To the Canibas tribe went Mugg, to try to persuade them to accept the treaty and release their captives. But he was not altogether successful. A pleasant story is told of one of Mugg's good deeds just before he sailed on his mission to the Canibas. A young man named Cobbet, the son of a clergyman of Ipswich, was among the captives found at Penobscot. He had been disabled by a musket wound, and, in that condition, delivered over to one of the most brutal and ferocious of the savages. Mugg, who had friendly relations with many of the English, had met the young man before, and, instantly recognizing him in the keeping of his cruel master, called him by name.  "I have just seen your father in Boston," he said, "and I promised him that his son should be restored to him. You must be released, according to the treaty." Madockawando and an English captain were standing by. The old chief knew that Cobbet's fiendish master would not allow him to go alive without a ransom, and he quickly turned to the English captain, and begged him to give, as a ransom, a gayly ornamented military coat which he had at hand. The captain delivered up the coat forthwith to the grimly satisfied savage, and young Cobbet was sent in safety to his home. An expedition consisting of two vessels, with ninety Englishmen and sixty friendly Natick Indians on board, was sent by the General Court to Casco and the Kennebec, to subdue the Indians in those parts, and to deliver the English captives detained in their hands. One vessel was commanded by Major Waldron, and the other by Major Frost. They made their first landing at Mare Point, in Brunswick.. The Indians who met them as they stepped on shore were led by Squando and Simon the Yankee-killer. Simon denied all accusations of intended hostilities, and declared that the Indians desired only peace, and had sent Mugg to the English for that purpose. The next day an unfortunate occurrence occasioned fresh difficulties. A large fleet of canoes was discovered rapidly drawing near to the vessels, and at the same time the log house of a settler was seen to be in flames. The English naturally supposed that the Indians had begun, in their usual way, to burn, pillage, and butcher. A company of armed men was immediately landed, and commenced a fire upon the Indians. The Indians retaliated. When at length a flag of truce was raised, the sagamores explained that the house took fire accidentally. They also declared that they had meant to return the captives, according to the treaty, but the weather had been so cold and the snow so deep that they had been unable to do so. The English, who could not be said to have covered themselves with glory in this enterprise, again set sail and crossed the wintry seas to the western shore of the Kennebec, opposite Arrowsic Island, where they landed. There half the men were set to work building a garrison. With the remainder of his men, in the two vessels, Major Waldron sailed to Pemaquid, where it had been arranged that a council should take place. He met there several sachems with Indians from various tribes. Major Waldron called upon these Indians to help the English to subdue the Indians who still remained hostile and refused to release their prisoners. One of the old sagamores replied: "Only a few of our young men, whom we cannot restrain, wish to enter upon the warpath. All the captives with us were intrusted to our keeping by the Canibas tribe. For the support of each one there are due to us twelve bearskins and some good liquor." The liquor was promptly forthcoming, and ransom was offered, but as yet only three captives were released. As the council met again in the afternoon, Major Waldron, who had previously suspected treachery, discovered some weapons where the Indians had concealed them. He seized a weapon and brandished it furiously, crying out that they were perfidious wretches, who had meant to rob and then kill them. This may or may not have been true; the savages were certainly often guilty of treachery. At all events, a wild panic followed. The Indians, unarmed, fled in dismay, and were pursued by armed men from the vessels, who mercilessly shot them down. Some of the Indians threw themselves into a canoe and pushed off in it. The canoe was upset, and five were drowned, while the rest were captured in trying to escape. Two chiefs and five other Indians were shot dead. Megunnaway, an old chief, was shot, after being dragged on board one of the vessels by Major Frost and one of his men. Majors Waldron and Frost returned to Arrowsic, carrying with them much plunder in the shape of goods and provisions taken from the Indians. One authority says, somewhat ambiguously, that the provisions "amounted to a thousand pounds of beef." At Arrowsic they shot Indians and took an Indian woman prisoner, sending her up to the Canibas, the stubborn keepers of captives, to demand an exchange. Leaving forty men in charge of their garrison on the mainland, they returned to Boston, boasting that they had not lost a single one of their number. But the disastrous result of their expedition had been to exasperate the Indians and inflame them to greater violence. This exasperation of the Maine Indians was increased when their ancient traditional enemies, the Mohawks, were hired by the English to help make war upon them. They immediately planned to destroy all the important points in Maine that they had not already laid waste. They adopted their old method of shooting down from ambush every white person within range. They shot down and instantly killed, in this way, nine visitors to the Arrowsic garrison. The holders of the fort were terror-stricken, and abandoned the place, distributing themselves about at stronger garrisons. At York and Wells the savages shot down men at work in the fields and standing in their cabin doors. Women and children dared not venture out of their houses, lest they should be carried away captive. The men whom they took prisonerß they put to death with horrible tortures. The garrison at Black Point was a strong one. For three days and nights the force under Lieutenant Tappan fought bravely in its defense. The great chieftain Mugg was here instantly killed. This was a severe blow to the Indians, who were always seriously affected by the death of their chiefs; and Mugg was one of those for whom they cherished a superstitious reverence. It was perhaps in reprisal for the loss that they renewed their fiendish tortures upon their captives. After the death of Mugg the Indians abandoned their attack on the Black Point garrison. But the end was not yet; and there was soon to take place there one of the fiercest and bloodiest battles of the long warfare. Two months afterwards the Black Point garrison was reŽnforced. A company consisting of ninety white men and two hundred friendly Natick Indians was sent there by the General Court. The Indians had prepared an ambuscade, and the white men allowed themselves to be entrapped. Captain Benjamin Swett and Lieutenant Richardson, the officers in command, were brave but reckless men. The Indians sent out a decoy which drew the ninety white men from the fort; then they feigned a retreat, and the English guilelessly pursued them until they were hedged in by a swamp and a thicket, both filled with Indian warriors. The hidden foe made a frightful onslaught. Lieutenant Richardson was instantly killed; and Captain Swett, wounded and fighting still, until exhausted by loss of blood, was cut to pieces by an Indian's tomahawk. Sixty of the men were killed. On the 12th of August, 1678, the English commissioners met Squando and the sagamores of the Kennebec and the Androscoggin tribes, and some simple articles of peace were drawn up and agreed upon. The hostilities were to cease. All captives on each side were to be surrendered without ransom. Every English family was to pay one peck of corn annually as a quitrent for the land it had gained from the Indians; and Major Phillips of Saco, who had very extensive possessions, was to pay one bushel each year. Peace was heartily welcome, for Maine's losses and suffering in the war had been very great. Two hundred and sixty had been killed or carried into captivity, and the wounded were unnumbered. A hundred and fifty captives were, after months of suffering, restored to their friends. So King Philip's War was over, in Maine as well as in Massachusetts, and for ten years the Maine settlers enjoyed comparative peace and security. But in 1688 difficulties between the French and the English aroused the Indians, who allied themselves with the French, to fresh hostilities. And they had not forgotten their old grudge against Major Waldron. The French and Indians had captured the strong fortress at Pemaquid, and then seized Falmouth and Newcastle. At Saco they were repulsed, but they surprised the settlement at Dover, and killed the inhabitants ruthlessly. A great company of them attacked Waldron's house, frantic in their desire for revenge upon their old enemy. Waldron was now eighty years old, but still strong and of undaunted courage. With his sword he defended himself, and drove the Indians from room to room until, at last, one struck him down, from behind, with his hatchet. Then they seized him, and dragged him into the living room, setting him upon a table in his own armchair. While he sat there, they ordered a supper prepared for them, and ate it, while they jeered at him. When they had finished, they took off his clothes, and submitted him to dreadful torture.  They gashed his breast with knives, and said mockingly, "So I cross out my account!" They cut off joints of his fingers, saying, "Now will your fist weigh a pound?" When they had amused themselves sufficiently in this way, they allowed him to fall upon his own sword, and thus end his torments. It was said that Major Waldron had, in his time, seized, and sent as slaves to Bermuda, a hundred Indians. |