| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2009 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

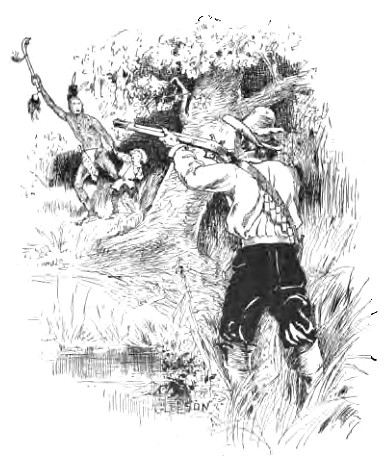

X. SIMON, THE YANKEE-KILLER.

AFTER the death of King Philip, some of the fiercest of his followers fled to Maine and distributed themselves among the eastern tribes. Their language was radically the same as that of the Maine Indians, but they used a dialect as different as was the cut of their hair. They were madly warlike, and of the superstitious sort, believing themselves commissioned by the Great Spirit to destroy the English. Some of these fugitive Indians could speak English, and three of the most bloodthirsty had acquired the English names of Simon, Andrew, and Peter. These three had escaped to the Merrimac River, a little while before the downfall of King Philip, and tried to conceal themselves among the Penacooks, who had remained neutral through the war. But the Penacooks surrendered them as murderers, and they were confined at Dover for many months, at length making their escape and fleeing to Casco Bay. They were all villains, but Simon, surnamed the "Yankee-killer," was the worst. He boasted that he had shot at many white settlers, and had only once failed in bringing his man to the ground. He had killed some settlers and taken others captive in Bradford and Haverhill. He escaped from Dover prison, made his way to Casco, and went to Anthony Brackett's house, where he represented himself as a "praying Indian," and completely won the confidence of the simple-hearted settler. He was a shrewd rascal, and, like Squando and Passaconaway, was accredited-by the Indians with a knowledge of the arts of magic. He apparently accepted the religion offered him by the missionaries, and regarded it with superstitious awe, as a superior kind of necromancy. Anthony Brackett had lost a cow, and Simon, assuming great friendliness, declared that he would find the Indians who had killed it, and would bring them to Brackett's house, of course with the understanding that payment or satisfaction of some sort was to be obtained from them. But Simon came at the head of a company of Indians, boldly entered the house, and took possession of Brackett's firearms. They were the Indians, Simon declared, who had killed his cow, and he had kept his promise. Now his friend Anthony might take his choice, to serve the Indians or be slain by them. Brackett chose to serve, and the savages bound him, his wife and five children, and a negro servant. Mrs. Brackett's brother, Nathaniel Mitten, resisted, and they instantly killed him. Brackett lived on a large farm at Back Cove, in Falmouth. There were clearings in the wilderness all about the cove, with cabins and small farms. Around the cove, at Presumpscot River, that day, Benjamin Atwell and Humphrey Durham were helping their neighbor, Robert Corwin, to get in his hay. The stillness of the beautiful August day was broken by the report of guns. Simon's men came from Anthony Brackett's, in one of the wild frenzies that often seemed to seize them as soon as they had shed blood, and shot down the three haymakers, who had no means of defense. They then went from one cabin to another, burning, slaying, and taking prisoners. Richard Pike and another man, who chanced to be in a canoe on the river, heard the sound of guns, and saw a little boy running, wild with terror, toward the river, pursued by the maddened, yelling savages. They were firing at the boy, and the bullets whistled over the heads of the men in the boat. Simon himself demanded from the river bank that the men should come ashore, but they plied their paddles for dear life; and as they did so they shouted the alarm to the inmates of the houses along the river, bidding them run for their lives to the garrison house. The first settlers of Portland had built their homes on the promontory, a hundred and sixty feet above the level of the sea, then called Cleaves Neck, and here they had erected their garrison house to protect them from their savage foes. But on this day those who had escaped to the garrison were few and feeble, and so terror-stricken that they dared not await the attack from the infuriated, merciless savages. They huddled together in the few canoes at hand, and sought refuge on the island near the harbor's mouth, now known as Cushings Island. From there they sent a messenger across the water to Scarborough (then known as Black Point) for aid. After night fell, a small party of men paddled bravely across the harbor and secured some powder, which they had left behind them in their hasty flight, and which, fortunately, the ransacking Indians had failed to find. Some of the other settlers succeeded in escaping the next day, and joined the fugitives on the island. They were in utter destitution, their lives alone being left to them. Everything in their homes was plundered or destroyed by the Indians. They were helpless, in the wilderness, with the bitter winter coming on. Casco Neck was depopulated and laid waste. Thirty-four persons were either killed or carried into captivity. As soon as the dreadful news reached Boston the General Court sent a vessel with provisions to the starving - outcasts on Cushings (then called Andrews) Island. The following letter, written from Portsmouth at this time, will give the reader some conception of the terror of those days. The letter was addressed to Major General Denison at Ipswich.

"This serves to cover a letter from Captain Hathorn, from Casco Bay, in which you will understand their want of bread, which want I hope is well supplied before this time; for we sent them more than two thousand weight, which, I suppose, they had last Lord's-day night. The boat that brought the letter brings also word that, Saturday night, the Indians burned Mr. Munjoy's house, and seven persons in it. On Sabbath day, a man and his wife, one George, were shot dead and stripped by the Indians at Wells. Yesterday, at two o'clock, Cape Nedick was wholly cut off; only two men and a woman, with two or three children, escaped. So we expect now to hear of further mischief every day. They sent to us for help, both from Wells and York; but we had so many men out of town that we know not how to spare any more. "Sir, please send notice to the council that a supply be sent to the army from the bay; for they have eaten us out of bread, and here is little wheat to be gotten, and less money to pay for it. The Lord direct you and us in the great concerns that are before us; which dutiful service presented in haste, I remain, sir, "Your servant, "RICHARD

MARTIN."

Anthony Brackett and his wife made their escape in a remarkable manner. It will be remembered that they were the first victims of Simon's raid, on that August day when the peaceful harvesting was going on at Casco Neck. When the Indians who had taken them captive, with Brackett, his wife, five children, and a negro servant, had reached the north side of Casco Bay, they heard the news of the taking of Arrowsic garrison house in Kennebec, with all its stores. They were overjoyed at this, and were anxious to be on hand to share the booty. Simon, notwithstanding his necromancy and superstition, had always a practical mind and was especially eager for gain. The Indians were in such haste to reach Kennebec that they promised Brackett and his wife a share of the spoils if they would hasten after them, bringing along a burden which each had been given to carry. Mrs. Brackett had seen an old birchen canoe lying at the waterside, and was inspired by the hope that it might be a providential opportunity offered for their escape. She first prudently asked the Indians to let the negro, their own servant, help them to carry their burdens, a request which Simon immediately granted. Then they begged a piece or two of meat, which was not denied them, Simon showing the curious mixture of kindness and ferocity which always distinguished him, as well as several of the other more noted Indians. Thus being furnished with help and provisions, the Indians leaving them to follow behind with their burdens and a young child, they could but look upon the whole circumstance "as a divine mandate to shift for themselves."  Mrs. Brackett also found a needle and thread in the house where they staid, on the east side of the bay, and with that she mended the canoe so that it was watertight. They all hastily embarked, and in that old canoe, which had been abandoned as being past repair, they crossed a water space eight or nine miles broad. They were in danger and in great terror of meeting Indians at Black Point, but fortunately the savages had just gone. Instead of hostile savages, they found at Black Point a vessel bound for Piscataqua, on which they made their final escape from the Yankee-killer and his savage horde. Anthony Brackett's brother-in-law writes pathetically to his mother of the dreadful calamity:

"HONOURED MOTHER: After my Duty and my wife's, presented to yourself, these may inform you of our present health, of our present being when others of our friends are by the barbarous Heathen cut off from having a being in this World. The Lord of late hath renewed his Witnesses against us and hath dealt very bitterly with us, in that we are deprived of the Societie of our nearest Friends, by the breaking in of the Adversarie against us. "On Friday last, in the Morning, your own son, with your two sons-in-law, Anthony and Thomas Brackett, with their whole Families were killed and taken by the Indians, we know not how; 'tis certainly known by us that Thomas is slain and his wife and children carried away captive. " And of Anthony and his Familie we have no Tidings and therefore think that they might be captivated the Night before, because of the Remoteness of their Habitation from neighbourhood. "Goodman Corbin and all his Familie, Goodman Lewis and his wife, James Russ and all his Familie, Goodman Durham, John Munjoy and Daniel Wakeley, Benjamin Hadwell and all his Familie are lost. All slain by Sun an Hour high in the Morning and after. " Goodman Wallis his dwelling House, and none besides his, is burnt: There are of men slain t i; of women and children 23 killed and taken. We that are living are forced upon Mr. Andrews his Island to secure our own and the Lives of our Families. We have but little Promise and are so Few in Number that we are not able to bury the Dead till more Strength come to us. The Desire of the People to yourself is that you would be pleased to speak to Mr. Munjoy and Deacon Phillips that they would entreat the Governor that forthwith Aid might be sent to us, either to fight the Enemie out of our Borders, that our English corn may be inned in, whereby we may comfortably live, or remove us out of Danger that we may provide for ourselves elsewhere. Having no more at Present but desiring your Prayers to God for his Preservation of us in these Times of Danger I rest, "Your dutiful Son, "THADDEUS CLARK. "From Casco Bay, 14, 6, 76. "Remember my love to my sister, etc." Direction: "These for his honoured Mother, Mrs. Elizabeth Harvy, living in Boston."

This band of Indians, under the leadership of Simon, began the hideous and wanton cruelties which make the details of the wars with the Indians in Maine too terrible to relate. Simon, an Indian like Squando, superstitious, and with a vague sense of a peculiar mission and peculiar powers, was utterly cruel and vindictive when his passion of hatred was thoroughly aroused. The taking of the Arrowsic garrison house, the news of which had helped the Brackett family to escape, was accomplished by a part of Simon's band which had separated from the others as a matter of strategy. It was one of the strongest fortresses in Maine, and the little settlement upon the beautiful Arrowsic Island was remarkably prosperous. Captain Lake, one of the proprietors, who was a rich man, had built a fine mansion there, as well as a strong fortress, with storehouses and mills. In the dead of the night a hundred Indians had landed stealthily upon the southeastern point of the island, made their lurking, catlike way through the woods, and crept in at the fort gate. Once inside the portholes, they, with fiendish yells, announced their mastery of the fort. The inmates, thus terribly surprised, made at first a fierce resistance; but seeing that the number of their enemies made it utterly hopeless, Captain Lake and Captain Davis, who were in charge of the fort, fled, with a few others, by a rear exit, and attempted to escape in a canoe to another island. The Indians pursued and fired upon them, and Captain Lake was killed. Captain Davis, wounded and crippled, was still able to land, and hid among the rocks, remaining for several days in severe suffering. Then, by the use of one arm, he succeeded in paddling to the mainland. The Indians burned all the buildings, with all provisions and supplies, upon Arrowsic Island, and left the pleasant little settlement a scene of utter desolation. About a dozen persons were so fortunate as to escape, while thirty-five were either killed or carried into captivity. The terrified settlers in the region fled from their homes to Monhegan, where it was easier to defend themselves than on the mainland. But clouds of smoke continually ascending from New Harbor, Corbins Sound, and Pemaquid, warned them that the savages were still at their terrible work of slaughter, pillage, and destruction; and in destitution and despair they crowded on board a vessel, and sailed for Piscataqua and Salem. On Munjoys (now Peaks) Island, about three miles from "the main," there was an old stone house which served as a garrison for many families of settlers fleeing for their lives from their burning homes. All along the coast, for sixty miles east of Casco Bay, the ravages of the Indians extended. The sunshiny peace and plenty of the summer had given way to terror and death and destitution. Again and again the settlers, with what seems an astonishing lack of prudence, allowed themselves to be surprised by the Indians under the leadership of the wily Simon. Some of the fugitives escaped to a garrison house on Jewells Island, and were pursued by the Indians, who were so elated that they no longer gave themselves the trouble of any secrecy or ambush. They landed on the island openly and with their dreadful war whoops. Strange to say, there was no sentinel oh the watch, no guard whatever. The men had all gone fishing, the women were washing at a brook, the children were scattered about the shore. The Indians immediately took possession of the house, cutting off the retreat of the women and children, and leaving the men no opportunity to return.  One small boy, left alone in the house, bravely fired two guns and shot two Indians. The men, off in fishing boats, heard the guns, and knew what was happening. One man rowing rapidly to shore was seen by his little son, who rushed to meet him. An Indian pursued the child, and seized him just as he reached the shore. The father leveled his gun and could have shot the Indian, but dared not lest he should also kill his child. He fled to Richmans Island for aid. The other men, brave, although they must have been hopeless, cut their way through the Indians and regained the fortress. In this desperate effort two were killed, and five, probably disabled by wounds, were made prisoners and carried away by the victorious savages. The Indians, who never exposed themselves to the guns of the settlers in the open field, hurried across the bay to Spurwink with their prisoners. A government vessel came, soon after, and carried the remaining Englishmen to a place of safety. A band of Indians, led by Simon, crossed the Piscataqua River to Portsmouth, burned a house, and took a woman with a baby captive, and also a young girl. There was an old woman in the family, but Simon said she should not be harmed, because she had, years before, shown kindness to his grandmother. He also gave the infant into her care. Simon was one of the "praying Indians," and seems certainly to have known the better way, if he did not follow it. It is related that Simon once sat with an English judge to decide upon a criminal case. Several women, Simon's wife among the rest, had committed some offense. Judge Almy thought that they should be punished with eight or ten stripes each. "No," said Simon; "four or five are enough. Poor Indians are ignorant. It is not Christian to punish as severely those who are ignorant as those who have knowledge." The judgment prevailed. But then Judge Almy inquired: "How many stripes shall your wife receive?" Simon promptly replied: "Double, because she had knowledge to have done better." Judge Almy, out of regard for Simon, remitted his wife's punishment entirely. Simon seemed much disturbed, but at the time he said nothing. Soon after, however, he remonstrated very severely against the decision of the judge, saying that his wife had had a chance to learn better. "To what purpose," said he, "do we preach a religion of justice if we do unrighteousness in judgment?" This event took place when Simon was an aged man, and when, by the power of Christianity, his character may have been greatly changed. Like so many of the wary old sagamores, Simon survived all the fierce and bloody wars in which he invariably " graced battle's brunt," and died at a very great age, probably in hope of happy hunting grounds hereafter. |