|

1999-2002 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click Here to return to |

|

1999-2002 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click Here to return to |

V

OVER BEACON HILL

As we were strolling down the Beacon Street Mall while the Englishman remarked the charm of the Beacon Street border largely of old-time architecture, disfigured though it is in spots by the intrusion of incongruous reconstruction, the Artist recalled the earliest extant painter’s sketch of the Common, of a date some sixty years after Bennett’s pen picture, which includes this border.

It is a water color representing the Common and Beacon Street as they appeared in or about 1805 — 1806, when the making of Park Street was under way, and the development of Beacon Hill west of the new Bulfinch State House into a fair urban West End, was progressing. Although the border was occupied in part in the Province period our guest was told that no piece of provincial architecture is seen in the line. The oldest dates back only to 1804—1805, about the period of this painting. Several pieces are of the second decade of the nineteenth century. Others are examples of the spacious Boston domestic architecture of the eighteen thirties.

From its first occupation the border was a favored seat of Boston respectability. When Bennett wrote in 1740 two seats were here, one at the head of the line, the other at the foot. The street was then a lane through the Common “and so to the sea” — the Back Bay, the bound of this side of the Common then being the hill. The house at the head was the mansion of Thomas Hancock, uncle of the famous John, then new, it having been erected in 1737, and pronounced one of the most elegant in Town. At the foot or back on the hill slope, were “Bannister’s Gardens”, the estate of Thomas Bannister, merchant — or at this time of his heirs — occupying the six-acre home-lot of William Blaxton, the first planter, which he reserved from the sale of the peninsula to the inhabitants. Between these two places the hill spread out much as in its primitive state. The Hancock mansion was the first house to be erected on the top of the hill west of the summit, or the highest of the three peaks. The mansion-house stood in solitary grandeur with no neighbor westward for some thirty years.

Then in or about 1768 John Singleton Copley, the painter, built here, setting his house midway :down the line, about where we see the distinguished double-swell front stone house, now the home of the Somerset Club, originally the early nineteenth-century mansion-house of David Sears, merchant, eminent in his day Copley at this time was at the height of his prosperity as the court painter of Boston gentility, and upon his fortunate, and happy, marriage in 1769 with Miss Susanna Clarke, the fifth daughter of Richard Clarke, a wealthy merchant, agent of the East India Company in Boston, and later one of the consignees of the tea which the Bostoneers threw overboard, he acquired a large part of the hill west of the Hancock holdings, including the Blaxton six-acre lot which had passed from the Bannisters. Thus Copley became the holder of the largest private estate in the Town — a rare distinction for a painter of that day, or of any day.

From that time till after the Revolution the border was occupied for the most part by the Hancock and Copley places alone. Copley’s house has been attractively described as a comfortable roomy wooden mansion, or rather country house, of colonial yellow, lacking the elegance of its grander neighbor but refined, with pleasant gardens, ample stable and outbuildings. Copley called his domain “The Farm.” In this house he painted some of his best portraits. Trumbull, the younger painter, in his familiar description of a call upon him here, pictures him engagingly as the prosperous painter and social light. Copley left this house and went to England in 1774 with his father-in-law, never to return to Boston or to the country, although his heart was with the American cause. A year later, on the edge of the Siege, his family also sailed and joined him there. After the Revolution General Harry Knox occupied the yellow mansion for a season, and here portly Madam Knox, in her slimmer years the toast of the Continental army officers as the American Beauty, gave sumptuous dinners. Then in 1795, upon the selection of a site on the hilltop, west of the summit — the Hancock cow pasture — for the Bulfinch State House, and the beginning of its erection, the Copley domain was acquired by two astute Bostonians, Harrison Gray Otis and Jonathan Mason, who saw in the establishment of the new State House here their opportunity for a profitable real estate operation on a large scale. On their subsequent union of interests with two others, owners of contiguous lands, began the transformation of the hill from a place of fields and pastures into a sumptuous residential quarter. In course of time the eminence was graded, West Hill, or Mount Vernon, the third peak, on the western side, was cut down, and the new West End of pleasant streets and fair dwellings rose, bringing fortune to the syndicate, and renown to Beacon Hill.

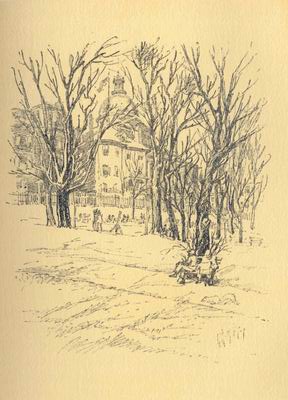

Dome of the State House, and site of the old John Hancock

House

The picture of 1805—1806 shows, at the head of the Beacon Street line, the new Bulfinch State House, completed in 1798. Next west facing the Street in a row, appear the Hancock mansion-house, carriage-house, and stable. At this time the mansion was occupied by Madam Scott, John Hancock’s widow, who had married one of his ship masters, Captain James Scott, and was dispensing the hospitality of the house as graciously if not so lavishly as in Governor John’s day. The estate was yet one of the largest and finest in Town. When Thomas Hancock died in 1764 it comprised, with the mansion-house and various outbuildings, gardens, orchards, nurseries, and pastures; and extended along Beacon Street to the present Joy Street, back over the hill to Mt. Vernon and Hancock streets, and over the site of the Bulfinch State House to the summit. All this he devised to his widow, along with his “chariots, chaises, carriages, and horses”, and “all my negroes”, and with a neat sum of money, making Lydia Hancock, daughter of a Boston bookseller, the richest widow that had to that day ever lived in Boston. She died in 1777, when the estate passed by her will to John Hancock, her favorite nephew, who maintained it in all its glory and made it historic, till his death in 1790. He died in testate, having been able on his deathbed to dictate only the minutes of a will, in which, it is said, he gave the mansion-house to the Commonwealth.

It remained much in its original state a respected landmark long after the upbuilding of the lands about it. At length, in 1863, heroic efforts of citizens to secure its reservation by the State as a permanent memorial having failed, it was demolished, to the keen regret of all Bostonians even to the present day. Its site is marked by the two imposing heavy-faced houses of the brown-stone period of domestic architecture, near the unique foot passage of Hancock Avenue alongside the State House grounds. The upper one is now a publishing house, the first of a succession of old-time mansions along the line transformed, without marring their rare façades, into book-producers’ headquarters, which suggests the colloquial title of “Publishers’ Row.” The houses next below the two brown-stones, occupying the remainder of the front of the old Hancock estate to the Joy Street corner, are all of early nineteenth-century date and associated with the names of famous Boston merchants. The mansion at the corner was sometime the seat of George Cabot, distinguished in his day in public as in mercantile life and as the astute head of the Essex Junto. Just below the lower Joy Street corner we have pictured in the 1805—1806 water color, a neat wooden house with pillared front, and of a “peach-bloom” color. This was erected before 1792 as the country seat (for this part of the Town was counted suburban at that time) of Doctor John Joy, one of the owners of land contiguous to the Copley domain who became a member of the syndicate that developed the hill. His estate occupied the block between Joy and Walnut streets, and extended back up the hill to Mt. Vernon Street. The peach-bloom house remained till 1833, when it was removed, and upon the estate were erected three houses on the Beacon Street front, and four on Joy Street, all of which, save one, are still retained, good examples of the highest type of the Boston swell-front. The first of the three on Beacon Street, which the present apartment-house, the Tudor, replaces, was occupied successively by merchants of distinction — Israel Thorndike; Robert Gould Shaw, grandfather of Colonel Robert Gould Shaw, commander of the first negro regiment recruited at the North in the Civil War, whose memorial by Saint Gaudens we have seen at the head of the mall facing the street; and Frederick Tudor, the “ice king,” who first introduced ice into the tropics and made a fortune in the adventure.

“No”, the Englishman who had heard the legend was answered, “it was not he who was the recipient of George III’s hearty reception at court, — ‘Eh? Tudor? One of us?’ It was his father, Judge Tudor, friend of Washington, and of his staff.” In the other two of these three houses have also lived notable merchants. So, too, were highly respected merchants the first occupants of the houses next below to the Walnut Street corner, both of an earlier date —erected about 1816 The first was the seat of Samuel Appleton, till his death in 1853 at the age of eighty-seven, the corner one, of Benjamin P. Homer. Next in the picture appears a brick mansion-house of quiet dignity, on the lower Walnut Street corner. This we see yet standing, presenting a side to Beacon Street instead of the front as originally, the front door having been shifted to the Walnut Street side when the lane that became Walnut Street was widened. It is distinguished as the oldest of all now on the line. It was built in 1804—1805 by John Phillips, lawyer, a Bostonian by family connections distinctively of the Boston “Brahmin” class, at that time the Town advocate and public prosecutor, afterward first mayor of the city; but of wider name as the father of Wendell Phillips, who was born in this house in 1811. At a later period it was a Winthrop house, the house of Lieutenant-governor Thomas L. Winthrop, accomplished gentleman, but, like the estimable John Phillips, generally known as the father of a more distinguished son, Robert C. Winthrop.

This is the last house in the line shown in the picture of 1805—1806. The two next below it, rich examples of the distinctive Boston type, date from 1816. The upper one was originally the mansion of Nathan Appleton, merchant and manufacturer, younger brother of William Appleton; the other, of Daniel P. Parker, a large ship-owner in his time. Of the David Sears stone mansion we have spoken. That next but one below, the brick mansion with yellow porch and luxuriant mantle of woodbine and wisteria, dates from the eighteen-twenties, originally built for Harrison Gray Otis, his second mansion erected on the Copley domain, and designed to combine elegance and comfort. Here Mr. Otis, one of the most courtly of Bostonians, lived the remainder of his gentlemanly life, dispensing, we are told, a refined hospitality. He died in 1848. Originally between the Sears and Otis mansions was a beautiful garden. The house next below was long the seat of Eben D. Jordan, one of the earliest of Boston’s retail “merchant princes.”

At the Spruce Street entrance where we turn from the mall for the stroll over the hill, we are opposite the site of the first Boston house and the seat of the first Bostonian, in which Winthrop and his associates at their coming found the amiable and cultivated Englishman so agreeably established, surrounded by his garden of English roses, his orchard growing the first American apple, and close by the “excellent spring” of which he had “acquainted” Winthrop when courteously “inviting and soliciting” the governor to come over from Charlestown and settle on his peninsula.

The pioneer cottage is supposed to have stood on or just back from this Beacon Street line somewhere between this Spruce Street and Charles Street; while the six-acre home-lot extended back up the hillside over what are now Chestnut Street, Mt. Vernon Street, and Louisburg Square to Pinckney Street. It is a fascinating picture which the historians have given us of this first Boston seat and of this first Bostonian. Blaxton had been living here alone some six years before the coming of the colonists, bartering with the Indians for beaver skins for trading, cultivating his garden and orchard, browsing among his books of which he seems to have had good store, and in neighborly communion with the three or four other Englishmen then established on islands in the harbor and on the near mainland, who had come out as he had with Robert Gorges in 1620. He was well born, a graduate of Emanuel, the Puritan college, Cambridge, with his degree of Bachelor of Arts in 1617, and Master of Arts in 1621. Though a nonconformist “and detesting prelacy,” he still adhered to the Church of England, continuing to wear his canonical coat. For a while after the settlement had begun he was little disturbed, probably because of the remoteness of his seat from the Town center on the harbor front, and lived along amicably with the Puritans. But at length his independent spirit rebelled, and he declared, so the tradition runs, “I came from England because I did not like the Lords Bishops, but I cannot join with you because I could not be under the Lords Brethren.” So, after the sale of his rights in the peninsula, with the exception of the home-lot, he bought a stock of cows with the sum he received, thirty pounds, and moved off again into the wilderness. His new home was established in Rhode Island on the banks of the river which afterward took his name — spelled Blackstone. He, however, retained pleasant relations with his Boston friends, and some years after his withdrawal he married in Boston a Puritan widow. He seems to have been a kindly gentleman, fond of nature and a lover of animals, and there is declared to be historical proof for the quaint story that he trained a moose-colored bull to bit and bridle and saddle.

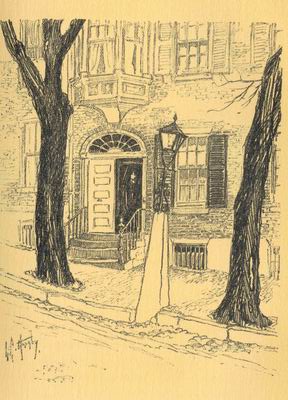

Colonial Doorway and Lamp on Mount Vernon Street

It is felicitous, our Englishman agreed, that the neighborhood of the home of this scholarly first Bostonian should have in after years become the favorite dwelling-place of men of letters, and the literary workshop of modern Boston. On the home-lot site, on this Beacon Street line, lived William H. Prescott during the last fourteen years of his life, his house being the upper of the two with pillared porticoes, we see below Spruce Street, Number 55. Here he prepared the greater part of his histories of the Spanish conquest when almost blind. On the cornice of his library-room were fixed those “crossed swords” to which Thackeray alludes in the opening lines of “The Virginians” — the swords borne by Prescott’s grandfather, Colonel Prescott, the commander at the Battle of Bunker Hill, and by his wife’s grandfather, Captain Linzee, the commander of the “Falcon,” one of the British warships in the same engagement. These crossed swords, our Englishman was told, are now to be seen similarly attached to a library wall in the house of the Massachusetts Historical Society, to which they were given after Prescott’s death. Also on the home-lot site, back of the Prescott house, on Chestnut Street, Number 50, Francis Parkman lived for twenty-nine years, during which appeared all of the seven volumes of his “France and England in North America.” Nearly opposite Parkman’s, at Number 43, lived the poet Richard Henry Dana for more than forty years of his long life of ninety-one years, which closed here in 1876.

Higher up, at Number 17, lived the poet-preacher, Cyrus A. Bartol, for more than sixty years of his almost as long life, which closed in his eighty-eighth year in 1900. Doctor Bartol’s house, and Number 15, his next door neighbors’ and kinsfolks’ — the Reverend and Mrs. John T. Sargent, both leaders in their time in “advanced thought” — were the meeting places alternately of the Radical Club.

This club was the descendant of the Transcendental Club of the forties in which sparkled such lights as Emerson, George Ripley, the founder of “Brook Farm,” and Margaret Fuller. At Number 16 John Lothrop Motley lived in the late forties and early fifties. Lower down, at Number 33, John G. Palfrey resided in the early sixties, but in the late sixties his home was in Louisburg Square. On West Cedar Street, opening from Chestnut Street down the hill, at Number 3, the “poet for poets,” and translator of Dante, Doctor T. W. Parsons, dwelt for some time in his latter years with his brother-in-law, George Lunt, a poet of the eighteen fifties, and his sister, Mrs. Lunt, writer of graceful lyrics. Sometime after the Lunts’ day Henry Childs Merwin, one of the small group of high ranking modern American essayists, occupied this house. At the upper corner of West Cedar and Mt. Vernon streets Professor Percival Lowell, the astronomer, who has made Mars so neighborly, dwells and works.

In Louisburg Square, at Number 2, William Dean Howells lived when editing the Atlantic Monthly. Number 10 was the home of Louisa M. Alcott in her latter prosperous years, and here her remarkable father, A. Bronson Alcott, passed in comfort his last days and serenely died. On Mt. Vernon Street, above Louisburg Square, at Number 83, William Ellery Channing lived during the latter years of his choice life, which closed in 1842. On the opposite side, at Number 76, Margaret Deland wrote the novels that first brought her fame. Later she was domiciled farther down on the hillslope, at Number 112. At the top of the hill, the house Number 59, with classic entrance door, was the last home of Thomas Bailey Aldrich. Earlier Aldrich had lived at the foot of the hill, on Charles Street, Number 131, now forlorn, then fair and beautiful with rich borders of shade trees — near neighbor of Oliver Wendell Holmes at Number 164, and James T. Fields, Number 148. His first home in Boston, to which he came to live in 1867, was the “little house on Pinckney Street,” of his pleasant description — Number 84, on the slope toward West Cedar Street.

On Pinckney Street up the slope have lived at different periods: John S. Dwight, master music critic, editor of Dwight’s Journal of Music (1852 — 1881), at Number 66; George S. Hillard, choice literary critic and essayist in the forties and fifties, at Number 62 in his latter years, earlier at Number 54, where Hawthorne was much a guest, and perhaps lived for a while with his friend (and whence, by the way, Hawthorne directed that unique letter to James Freeman Clarke, in July, 1842, engaging the good minister to marry him to Sophia Peabody, but without naming place or date); Louise Imogen Guiney, poet and essayist, at Number 16, before her removal to Oxford, England; Edwin P. Whipple, critic and essayist of leading in his time, and one of the literary lecturers most sought during the flourishing days of the “Lyceum” (he is said to have lectured more than a thousand times), at Number 11, near the head of the street. This was Whipple’s house for nearly forty years, till his death in 1886. His working study was a pleasant room on the second floor delightfully cluttered with books. In this house now refashioned is fittingly the literary workshop of Miss Alice Brown, story writer and prize play winner.

In this quarter, built up after London models with local variations — Chestnut Street of architectural refinement, embellished with doorways that Bostonians term colonial; quaint Acorn Street, a single carriage-width and with a single line of old style toy houses; reserved Louisburg Square; narrow Pinckney Street of variegated architecture and gentility; stately Mt. Vernon Street mounting from the river over the hill to the State House Archway and, as Henry James whimsically pictures, “fairly hanging there to rest, like some good flushed lady of more than middle age, a little spent and ‘blown’ ”, — here in this mellow quarter, with the London flavor yet lingering about it, our Englishman remarked that, like Daniel Neal’s “gentleman from London” a century back, he felt “almost at home” as he observed its character and its houses.

In Chestnut Street his attention was especially called to the group of three houses, Numbers 13, 15, and 17 — the Bartol house and its neighbors — for their architectural interest, and also because they were the first houses built on this street, and were the gifts of their builder, Madam Hepsibah Swan, one of the four composing the syndicate that developed this West End, to her three married daughters, in about 1810. Madam Swan was the wife of that remarkable Colonel James Swan of whose mansion-house on Tremont, then Common, Street beside the Common, we have spoken. On Mt. Vernon Street the upper line of broad-breasted, spacious mansions of a past sumptuous style, set back from the public sidewalk in aristocratic seclusion, impressed our guest as the distinguishing note of the street. The fine old colonial mansion with pebble-paved courtyard, the third in the group of three houses next this block and just above Louisburg Square, the Englishman was told, was the first mansion house that Harrison Gray Otis erected for his own occupation on the Copley purchase, and dates from about 1800. In Louisburg Square he was pointed to the central enclosure bedecked with tall trees, and toy statues at either end, as the place of Blaxton’s “excellent spring.”

There was the “dark side” of the hill, the slope north of Pinckney Street, that we did not penetrate, for the atmosphere that once gave this side peculiar distinction has gone, and it is no longer interesting, or over-clean. It was the “ dark side” from the free negro settlement occupying the north slope below Myrtle and Revere Streets before the Civil War and after, and as a center of anti-slavery agitation. The line between the haven of self-satisfied middle-classism on the south side and the north side residential quarter with its colored fringe, was sharply drawn. Fifty or sixty years ago over and on the hill’s brow in comparative obscurity were nurtured the seeds of anti-slavery and abolitionism later to bloom so terribly. After dark in the eighteen forties and fifties these little streets must have reeked with sedition against respectability. It was in the schoolroom of the little negro church on Smith Court off Joy (then Belknap) Street, and below Myrtle Street, that on that bitter cold, snowy January night, in 1832, the New England Anti-Slavery Society was organized by the small band who had been barred out of Faneuil Hall, when Garrison uttered his memorable prophecy: “We have met here to-night in this obscure schoolhouse; our numbers are few and our influence limited; but mark my prediction. Faneuil Hall shall ere long echo with the principles we have set forth. We shall shake the Nation by this mighty power.” The little meeting house was the scene of many more abolition meetings, and it might have been mobbed had it not been of stout brick. It yet stands in the little court, but is now, and long has been, a Jewish synagogue.

At the head of Mt. Vernon Street as we approached the Archway we crossed the gardens of the old Hancock place, or the site of them, between Hancock Avenue and Hancock Street. The Archway is a quite modern affair, we observed, and marks great changes made in the topography hereabouts. It dates back only to 1889—1895, with the erection of the State House Annex, the second addition to the Bulfinch Front, and preserving the traditions of the original structure, beneath which it passes. Before that time Mt. Vernon Street continuing, as the Archway now carries it, to the farther side of the State House, there took a sharp turn to the right and passed into Beacon Street nearly opposite the head of Park Street. It was then lined with fine houses, mostly Boston swell-fronts. From its north side at the turn opened Beacon Hill Place, a delightful foot passage to Bowdoin Street, bounded by three aristocratic houses, all historic from the character of their occupants at different periods. These pleasant houses and street lines were swept off to make way for the Annex, and for the park at the side, State House Park. Also went down the Beacon Hill Reservoir, a massive fortress-like structure on the Hancock Street line, facing Derne Street, with noble arches on its front, built in 1849, and called in its day the noblest piece of architecture in the city. The Annex and the space at its park side mark the site of the summit, or highest of the three peaks of the hill; while the pillar of stone topped with an eagle which we see in the park facing Ashburton Place, is a duplicate of the monument that last crowned the peak in place of the beacon of Colony and Province days — the monument of Bulfinch’s design erected in 1790—1791, the first in the country to commemorate the Revolution. The peak remained unshorn, a beautiful grassy cone-shaped mound, behind the Bulfinch Front reaching almost as high as the gilded dome now reaches, till 1811. It was cherished then as it had been from Colony days as the crowning glory of the Town. A visit to its top for the fine view which it commanded was the finishing feature of the round of Boston sights. On pleasant summer evenings gay dinner or supper parties at the houses in its neighborhood were wont not infrequently to adjourn to the lookout for enjoyment of the moonlight, the gentle zephyrs, and flirtatious communion. The approach to it from the Mt. Vernon Street side was through a turnstile to a flight of steps leading part way up and joining a broad path in which convenient footholds had been worn. The way from Derne and Temple streets was direct to the monument by Beacon Steps, so called. The hill cutting beginning in 1811 occupied a dozen years, and was fittingly called “the great digging.” To-day the cutting into the park to make way for the twentieth-century State House wing, occupies, with the employment of the steam shovel in place of the hand-digger, not much more than a dozen days. With the completion of this wing, and its companion on the west side, greater changes will have been effected in this quarter; and, alas! Beacon Hill, which now alone retains in its richness the old Boston flavor, will have lost more of its earlier charm.