| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2015 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

|

CHAPTER

V

THE JAPANESE GIRL The word "obedience" has a large part in the life of a Japanese boy; it is the whole life of a Japanese girl. From her babyhood she is taught the duty of obeying some one or other among her relations. There is an old book studied in every Japanese household and learned by heart by every Japanese girl, called "Onra-Dai-Gaku"--that is, the "Greater Learning for Women." It is a code of morals for girls and women, and it starts by saying that every woman owes three obediences: first, while unmarried, to her father; second, when married, to her husband and the elders of his family; third, when a widow, to her son. Up to the age of three the Japanese girl baby has her head shaved in various fancy patterns, but after three years old the hair is allowed to grow to its natural length. Up to the age of seven she wears a narrow obi of soft silk, the sash of infancy; but at seven years old she puts on the stiff wide obi, tied with a huge bow, and her dress from that moment is womanly in every detail. She is now a musume, or moosme, the Japanese girl, one of the merriest, brightest little creatures in the world. She is never big, for when at her full height she will be about four feet eight inches tall, and a Japanese woman of five feet high is a giantess. This is her time to wear gay, bright colours, for as a married woman she must dress very soberly. A party of moosmes tripping along to a feast or a fair looks like a bed of brilliant flowers set in motion. They wear kimonos of rich silks and bright shades, kimonos of vermilion and gold, of pink, of blue, of white, decorated with lovely designs of apple-blossom, of silk crape in luminous greens and golden browns, every shade of the rainbow being employed, but all in harmony and perfect taste. If a shower comes on and they tuck up their gaily-coloured and embroidered kimonos, they look like a bed of poppies, for each shows a glowing scarlet under-kimono, or petticoat.

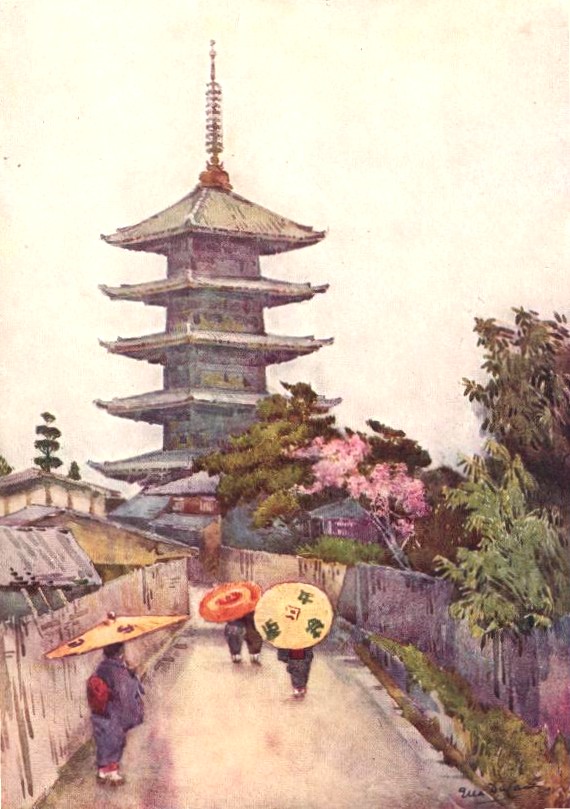

GOING TO THE TEMPLE Not only is this the time for the Japanese girl to be gaily dressed, but it is her time to visit fairs and temples, and to enjoy the gaieties which may fall in her way: for when she marries, the gates which lead to the ways of pleasure are closed against her for a long time. The duties of a Japanese wife keep her strictly at home, until the golden day dawns when her son marries and she has a daughter-in-law upon whom she may thrust all the cares of the household. Then once more she can go to temples and theatres, fairs and festivals, while another drudges in her stead. Marriage is early in Japan. A girl marries at sixteen or seventeen, and to be unmarried at twenty is accounted a great misfortune. At marriage she completely severs herself from her own relations, and joins her husband's household. This is shown in a very striking fashion by the bride wearing a white kimono, the colour of mourning; and more, when she has left her father's house, fires of purification are lighted, just as if a dead body had been borne to the grave. This is to signify that henceforward the bride is dead to her old home, and her whole life must now be spent in the service of her husband and his relations. The wedding rites are very simple. There is no public function, as in England, and no religious ceremony; the chief feature is that the bride and bridegroom drink three times in turn from three cups, each cup having two spouts. These cups are filled with saké, the national strong drink of Japan, a kind of beer made from rice. This drinking is supposed to typify that henceforth they will share each other's joys and sorrows, and this sipping of saké constitutes the marriage ceremony. The young wife now must bid farewell to her fine clothes and her merry-making. She wears garments of a soft dove colour, or greys or fawns, quiet shades, but often of great charm. She has now to rise first in the morning, to open the shutters which have closed the house for the night, for this is a duty she may not leave to the servants. If her husband's father and mother dwell in the same house, she must consider it an honour to supply all their wants, and she is expected to become a perfect slave to her mother-in-law. It is not uncommon for a meek little wife, who has obeyed every one, to become a perfect tyrant as a mother-in-law, ordering her son's wife right and left, and making the younger woman's life a sheer misery. The mother-in-law has escaped from the land of bondage. It is no longer her duty to rise at dawn and open the house; she can lie in bed, and be waited upon by the young wife; she is free to go here and there, and she does not let her chances slip; she begins once more to thoroughly enjoy life. It may be doubted, however, whether these conditions will hold their own against the flood of Western customs and Western views which has begun to flow into Japan. At present the deeply-seated ideas which rule home-life are but little shaken in the main, but it is very likely that the modern Japanese girl will revolt against this spending of the best years of her life as an upper and unpaid servant to her husband's friends and relations. But at the present moment, for great sections of Japanese society, the old ways still stand, and stand firmly. It was formerly the custom for a woman to make herself as ugly as possible when she was married. This was to show that she wished to draw no attention from anyone outside her own home. As a rule she blackened her teeth, which gave her a hideous appearance when she smiled. This custom is now dying out, though plenty of women with blackened teeth are still to be seen. Should a Japanese wife become a widow, she is expected to show her grief by her desolate appearance. She shaves her head, and wears garments of the most mournful look. It has been said that a Japanese girl has the look of a bird of Paradise, the Japanese wife of a dove, and the Japanese widow of a crow. |