| Web

and Book design, |

Click

Here to return to |

PARK

STREET CHURCH

THE lot

whereon the Granary stood, measuring one hundred and eighteen feet along Park

Street, was sold by the Town agents, November 10, 1795, for the sum of $8366 to

Major-General Henry Jackson, who commanded the Massachusetts Militia at the

time of the sale. He had served with distinction during the Revolution, and was

the owner of considerable real estate in the town. From him the Granary lot

passed to the control of Mrs. Hepsibah Swan, the widow of James Swan.

Thereafter it became the property of her daughters, who sold the premises,

April 13, 1809, to Caleb Bingham, book-seller and publisher; Andrew Calhoun,

merchant; and William Thurston, Esq., Trustees of the Church. The price paid

for this land was twenty thousand dollars.

A

subsequent deed to Samuel H. Walley, January 17, 1810, recites that “a Church

of Christ, called Park Street Church, had been gathered in the Town of Boston;

and a brick meeting-house lately erected on a street formerly called Centry

Street, and now called Park Place.” The Trustees “do permit and suffer the said

house and land to be used, occupied and enjoyed as and for a meeting-house or

place for the public, Protestant worship and service of God.”

The Granary

was removed in 1809, and the Church was built immediately afterward from

designs prepared by Peter Banner, an English architect and builder, of whom

little is known. The wooden capitals of the steeple are the handiwork of

Solomon Willard, the architect of Bunker Hill Monument. The mason-work was

under the supervision of Benajah Brigham. It was the intention of the Building

Committee to use common bricks; but better counsels prevailed, and face bricks

were employed. The building, now seen in its original red-brick dress, was

newly painted in 1906. At that time, to quote from a recent writer, “the

sympathetically toned gray of the body of the Church, with its white trimmings,

combined to give a pearly effect, which could not but convey to the coarsest apprehension

the fact that this Church was a pearl of great price for Boston.”

Henry James, the American novelist, described its style of architecture as “perfectly felicitous.” “Its spire,” he said, “recalls Wren’s bold London examples, like the comparatively thin echo of a far-away song; playing its part, however, for harmonious effect as perfectly as possible.” Mr. James regarded this Church building as “the most interesting mass of brick and mortar in America.” The weather-vane, which crowns the spire, is two hundred and seventeen feet above the street level. Many will recall the thrilling sight of a steeple-jack, engaged in regilding this vane a few years ago. It was not originally intended that the edifice should have a spire. But the Building Committee yielded to the prevailing sentiment that a Church occupying such a prominent site should be thus ornamented. And for more than a century the graceful spire has remained intact, defying the fury of winter storms; although it was observed to sway considerably during the great gale which destroyed Minot’s Ledge Light House in the middle of the last century.1

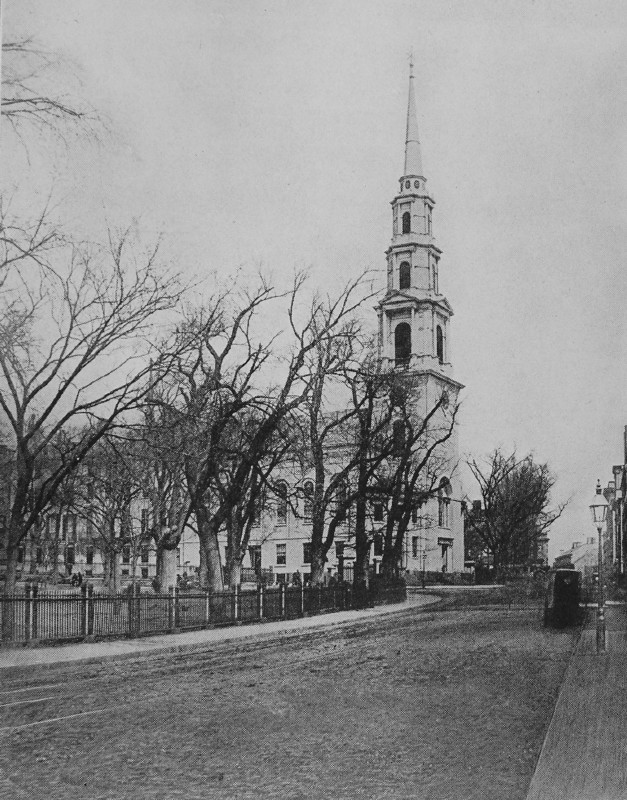

PARK STREET CHURCH ABOUT 1870

From a photograph owned by Dr. J. Collins Warren

The Park Street Church Society was organized at the

mansion of William Thurston, a well-known attorney, on Bowdoin Street, February

27, 1809; and in that house the first religious exercises of the new Society

were held. The Corner-Stone of the Church building was laid May 1, 1809; and

the total cost of the latter was somewhat over seventy thousand dollars. The

Dedication Sermon was preached by the Reverend Doctor Edward Dorr Griffin,

January 10, 1810; and he was installed as Pastor, July 31, 1811.

Mr.

Lindsay Swift, in his “Literary Landmarks of Boston,” wrote that Park Street

Church is an important strategic point; and that “all roads lead to Rome,

except in Boston, where they lead to, or certainly from this convenient centre

of the City’s life.” For many years the corner of Tremont and Park Streets has

been a rendezvous, and a point of departure, especially for strangers.

The

origin of the name” Brimstone Corner,” sometimes applied to this locality, has

been attributed to the fervid doctrines preached within the walls of the

Church. The true source of that name appears to be the historic fact that

brimstone, for use in making gunpowder, was stored in the building during the

War of 1812. There is also a tradition that in the early days of this Church,

sulphur was sprinkled on the sidewalk near by, to attract the attention of

wayfarers. In this building were founded the American Education Society (1815),

the Prison Reform Society, and the American Temperance Society (1826).

On the

Fourth of July, 1832, the song “America” was heard in public for the first

time, at a children’s celebration in Park Street Church. The author, Samuel

Francis Smith, then a theological student at Andover, Massachusetts, had

composed poetry from his childhood. Inspired by the words of a patriotic German

hymn, he determined to produce an anthem which should manifest the love felt by

him for his own country. “Seizing a scrap of paper, he began to write, and in

half an hour the words stood upon it substantially as they are sung to-day.”2

On Sunday forenoon, November 24, 1895, one of the

workmen engaged in excavating for the Tremont Street Subway, almost under the

front wall of Park Street Church, probably struck his pickaxe into a main

water-pipe, which burst; and the water shot up with such force that it broke

the window glass in the minister’s study, ruining its furnishings, and covering

with mud its carpet and luxurious upholstery. Fears were entertained that the

foundations of the building had been weakened. At the following evening service

the minister told the members of his congregation that it was an outrage to

permit the carrying on of such work at the very portals of the Church on a

Sunday. And with natural righteous indignation he referred to the Subway as “an

infernal hole,” in more than one sense. “And who is the Boss in charge of this

work?” he demanded. Then after a pause, he added, “It is the Devil!”

In 1809,

when Park Street Church was built, Boston still preserved the appearance of an

old English market-town. No curbstones separated the streets from the

sidewalks. The cows still browsed on the Common, and the Town Crier made his

proclamations. There were then but two houses of more than one story on the

present Tremont Street. “Colonnade Row had not been built, and Boston was a

city of gardens. There were only a few residences on Beacon Hill: its western

slope was a series of terraces. The business section of to-day still retained

its residential character, with its old-fashioned gardens, trees and churches.”3

In 1902

Park Street Church and its site were sold for one and a quarter million dollars

to a syndicate of business men, who proposed to erect in its stead a

sky-scraper office building. Thereupon a committee of influential persons was

formed, whose object was the preservation of the Church property. It was justly

claimed that the whole aspect of the Common and of the Granary Burial-Ground

would be irretrievably marred by the destruction of this impressive landmark.

The committee doubtless reflected the prevailing sentiment of the community, in

their plea that the preservation of the Church would avert a severe blow to the

architectural beauty of the City. And they maintained with reason that the

building could be made to serve as an important centre for educational and

civic work. Influenced, it may be, by the trend of public opinion, the members

of the syndicate failed to meet a condition of the transfer; namely, that they

should pay three hundred thousand dollars of the purchase money within a

specified time. Therefore it was announced in April, 1903, that the

preservation of the Church was assured. The published account of the

Semi-Centennial Celebration of the founding of Park Street Church, held in

1859, contains these eloquent words: “For nearly half a century this majestic

spire has withstood the burning heat of the summer’s sun, and the freezing cold

of inclement winters. The storms have raged and northwest winds have roared

around it; gales which have uprooted the massive elms of our magnificent

Common, have passed it unheeded; even the earthquake’s shock, and the

lightning’s fiery blast have shaken, yet spared it. And Time, old Time, which

subdues all things, has laid a gentle hand upon its head. What time and the

elements have suffered to endure, let man preserve!”

“I love

to stop before the beautiful Park Street Church spire,” said the Reverend J.

Edgar Park, in an Artillery Election Sermon, delivered in the New Old South

Church, June 7, 1920, “almost the last hold that the ancient town of Boston has

upon the cosmopolitan city; a spire that speaks still of the old residential

Beacon Street, and of the days when its bell called across the Common to its

congregation to gather in their meeting-house, to worship the God of the

Pilgrim Fathers. Here I feel that I am standing on one of the most historic and

beautiful spots, not only in this country, but in the whole world.”

All the

old meeting-houses of Boston, if we agree with an opinion expressed by former

Mayor J. V. C. Smith, M.D., in the year 1853, such as Park Street Church, the

Old South, and a few others with spires, were superior in architectural beauty

to the more modern edifices of higher cost. For, says our critic, “the genius

that is among us, ready to be exercised in the Metropolis of New England, seems

fated to be smothered by the overruling determination of old women and

Deacons!”

When a

Church was to be built in Boston, it was customary to have a committee appointed.

And oftentimes no two of any such a committee “had a rational notion of what

should, or should not be adopted in a plan. However classical, beautiful , or

grand the artist may have been in his projection, each one of the sapient

conservators on the committee must have a whim gratified, even if it is at the

expense of the artist’s reputation. Botch after botch follows, and when the

building is fairly completed, they are all laughed at for their stupidity, and

condemned for their vulgarity!”

If the learned gentleman could have seen some of Boston’s Church edifices of comparatively recent years, he might well have modified his above-quoted naïve utterances.

1 April 21, 1851.

2 C. A.

Browne, The Story of Our National Ballads.

3 The Preservation of Park Street

Church. Boston, 1903.