|

1999-2004 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click Here to return to |

VI.

CAMBRIDGE AND HARVARD COLLEGE

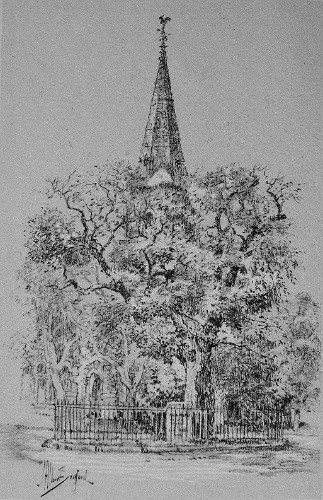

THE WASHINGTON ELM, GARDEN STREET, CAMBRIDGE.

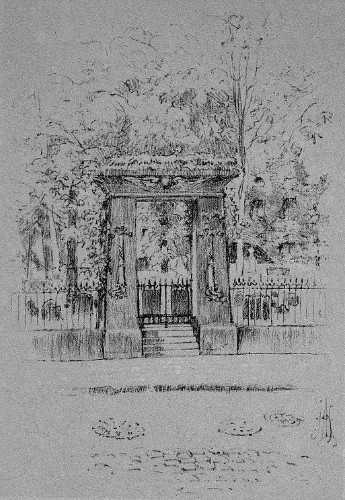

ENTRANCE TO THE OLD GRANARY BURYING GROUND, TREMONT STREET;

HERE LIES JOHN HANCOCK, HARVARD COLLEGE 1754; THE VICTIMS OF THE

BOSTON MASSACRE ARE BURIED HERE; ALSO SEVERAL SIGNERS OF THE

DECLARATION OF INDEPENDENCE

BY reason of common ancestry and interest, a close kinship unites Cambridge and Boston. Blood is thicker than water, even though the water constitute a physical barrier between them. Cambridge shares, and, if possible, intensifies the Boston spirit; yet it has its own unique and well defined individuality.

Some uncertainty seems to have persisted in the minds of the Puritan founders of Boston as to the permanency of their Shawmut location. The slopes of Trimount offered a very limited area for agricultural purposes; the settlers needed elbow room. Upon a seven-hundred-acre tongue of land almost completely engirdled by water, the problem of growth was serious. On the promontory, geographical contour simplified the matter of defence; so, in selecting a site for a town further inland, protection must be considered, along with the gained advantages of soil and space.

In December, 1630, the settlers decided to begin a new town at a spot nearly coincident with the present Harvard square, and "Newtowne" it was called for eight years. Here is a contemporary account of Newtowne, by William Wood, author of New England's Prospect, 1633:

"This place was first intended for a city, but, upon more serious considerations, it was thought not so fit, being too far from the sea, being the greatest inconvenience it hath. This is one of the neatest and best compacted towns in New England, having many fair structures, with many handsome contrived streets. The inhabitants, most of them, are very rich, and well stored with cattle of all sorts, having many hundred acres of land paled in with general fence, which is about a mile and a half long, which secures all their weaker cattle from the wild beasts."

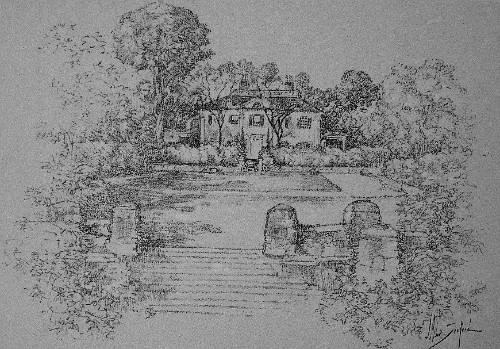

ELMWOOD, MT. AUBURN STREET, CAMBRIDGE; BIRTHPLACE OF JAMES

RUSSELL LOWELL.

Many of the Bostonians agreed to establish homes in the new fortified town, including Governor Winthrop, Thomas Dudley, the deputy governor, and the "assistants," who constituted the council, or legislative aids to the governor. Not all kept this promise. Dudley built his house near what is now Dunster street, two blocks from the Square. Winthrop, however, changed his mind, and though he actually built a house in Cambridge, he subsequently removed it to his lot on the corner of Milk street and old Corn Hill, in Boston. This frame dwelling was his second Boston residence. The first South Meeting House was built beside it, and afterward our own Old South, in 1729. When the British occupied the church, they pulled the ancient mansion to pieces and used it for fuel.

The "paling," a tall barrier of stout logs, extended from the Charles river to the creek that formed the north boundary of the town. It crossed the land now occupied by the College, on a line passing through or near the site of Gore Hall. No assault upon the paling is recorded, and as a defence against the Indians it need not have been built, since they were not of a menacing breed or disposition.

In his Wonder-Working Providence, Edward Johnson, whom we have had previous occasion to quote, wrote:

"When they had scarce houses to shelter themselves and no doores to hinder the Indians access to all they had in them ............ yet had they none of their food or stuffe diminished, neither children nor wives hurt in any measure, although the Indians came commonly to them at those times, much hungry belly (as they used to say) and were then in number and strength beyond the English by far."

This friendliness on the part of the aborigines was due to the conciliatory attitude of the colonists toward them; consider this injunction, which the settlers made their rule in dealing with the Indians:

"If any of the salvages pretend right of inheritance to all or any part of the lands granted in our patent, wee pray you endeavor to purchase their tytle, that wee maye avoide the least scruple of intrusion."

THE VASSALL HOUSE, HEADQUARTERS OF WASHINGTON, 1775-1776;

ALSO CALLED THE

CRAIGIE HOUSE AND LONGFELLOW HOUSE; IN THE FOREGROUND, LONGFELLOW PARK.

In spite of the intention of its founders, Cambridge failed to become the metropolis of Massachusetts. The Boston people did not flock thither; a Boston man hates to leave home, and the feeling seems to have taken shape very early in the history of the city. Although the General Court convened in Cambridge for a period, the town was never more than a considered possibility as a permanent capital. But as time passed, Cambridge came to occupy a position of fine distinction among New England cities.

In October, 1636, the General Court appropriated £400 "towards a school or college, whereof £200 to be paid the next year and £200 when the work is finished, and the next Court to appoint where and what building." In 1639 it was "ordered that the College agreed upon formerly to be built at Cambridge shall be called Harvard College." This was the year in which Stephen Daye started a printery in Cambridge, on a borrowed capital of £51, the first printing establishment in New England.

John Harvard gave his library and half his estate to the college, and in his honor the institution was named. Nearby, Master Corlett conducted a public grammar and preparatory school for fifty years.

He is said to have "very well approved himself for his abilities, dexterity and painfulness in teaching and educating of the youth under him." Painless education is a modern invention, like other anesthetic procedure.

William Wood, 1654, said of Harvard: "The edifice is very faire and comely within and without, having in it a spacious hall ............ a large library, with some books in it." The Italics are ours.

Edward Johnson refers to the college enclosure as "the yard," and today one seldom hears of the Harvard "campus." In old Newtowne days, the portion of the present quadrangle adjacent to the market place (now Harvard square) was called the "cow-yard." Today it is still the "yard."

The first three Harvard buildings were old Harvard, old Stoughton, and Massachusetts. The last mentioned, 1720, is the oldest college building now standing. To rebuild Harvard and Stoughton, money was raised by lotteries, authorized by the General Court, and of one such lottery the college itself won the capital prize, $10,000. The last was in 1811.

In Revolutionary times old Cambridge was a center for loyalists, many of whom were forced to leave the country, and suffer confiscation of their homes. One of these, Lieutenant-Governor Thomas Oliver, dwelt at Elmwood, afterwards the home of the poet Lowell. He signed an enforced resignation in 1774. During the war the house was used as a hospital. Later it was occupied by Elbridge Gerry, one of the "signers," who became governor, and afterwards vice-president. The poet's father acquired the property at the death of Mr. Gerry. The house was built previous to 1760, its name, Elmwood, dating back to the days of the elder Lowell.

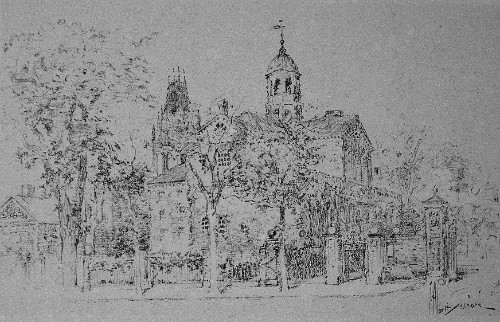

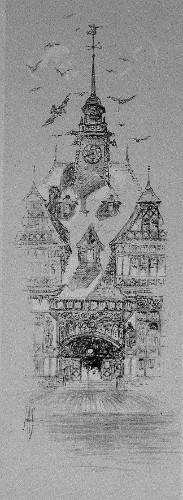

THE OLD GATE OF HARVARD COLLEGE; HARVARD HALL; BEYOND, THE

TOWER OF

MEMORIAL HALL; AT THE EXTREME LEFT, HOLDEN CHAPEL, 1744.

On a night neither recent nor remote, a Cambridge citizen going belatedly home along Garden street, encountered the oval iron fence that surrounds the Washington Elm. He felt his way around the circuit several times, then, terror-stricken, shouted, "Help, help, I'm locked in!"

The old tree still survives. the repeated rigors of our New England climate, and if the new forestry avail, may live indefinitely. But it has lost much of the spreading canopy under which Washington took command of the American army in 1775. It shares with the Craigie homestead the honor of having sheltered the great Commander. This was originally the estate of a rich Tory, Colonel John Vassall. General Washington took possession of the house in July, 1775, and chose for his personal use the southeast chamber, where afterward Henry Wadsworth Longfellow lived and worked. The poet himself guided many a visitor through the historic rooms, answering questions with gentle courtesy.

No American city has association with events of greater moment in our history than has Cambridge. Six men of Cambridge fell in the battle of Lexington. It was for many months the headquarters of the Revolution, and its citizens have helped shape the destiny of the nation. And in that golden generation of American letters just passed, the Cambridge immortals shared gloriously in laying the deep foundations of our national literature.

|

"Amid these fragments of heroic days, When thought met deed with mutual passion's leap, There sits a fame whose silent trump makes cheapWhat short-lived rumor of ourselves we raise. They had far other estimate of praise Who stamped the signet of their souls so deep In art and action, and whose memories keep Their height like stars above our misty ways." --James Russell Lowell. |

THE HEAD HOUSE, MARINE PARK,

SOUTH BOSTON.

Click the book image to continue to the next chapter