| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2010 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click

Here to return to

Castles and Chateaux of Old Navarre and the Basque Provinces Content Page Return to the Previous Chapter |

(HOME)

|

| CHAPTER XXIX

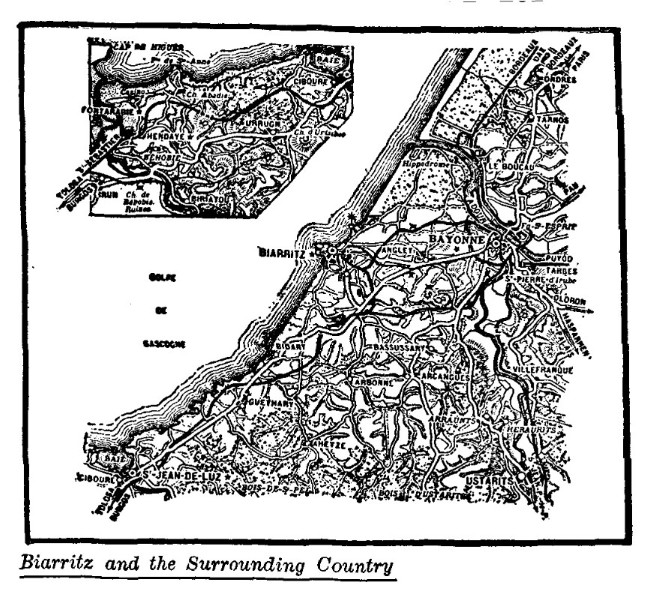

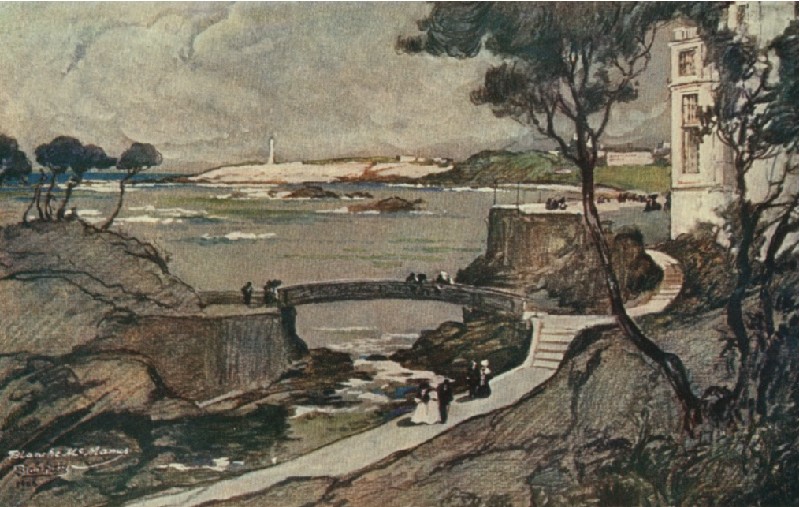

BIARRITZ AND SAINT-JEAN-DE-LUZ  BIARRITZ AND THE SURROUNDING COUNTRY IF Bayonne is the centre of commercial affairs for the Basque country, its citizens must at any rate go to Biarritz if they want to live "the elegant and worldly life." The prosperity and luxury of Biarritz is very recent; it goes back only to the second empire, when it was but a village of a thousand souls or less, mostly fishermen and women. The railway and the automobile omnibus make communication with Bayonne to-day easy, but formerly folk came and went on a donkey side-saddle for two, arranged back to back, like the seats on an Irish jaunting-car. If the weight were unequal a balance was struck by adding cobble-stones on one side or the other, the patient donkey not minding in the least. This astonishing mode of conveyance was known as a cacolet, and replaced the voitures and fiacres of other resorts. An occasional example may still be seen, but the jolies Basquaises who conducted them have given way to sturdy, bare-legged Basque boys — as picturesque perhaps, but not so entrancing to the view. To voyage "en cacolet" was the necessity of our grandfathers; for us it is an amusement only. Napoleon III, or rather Eugénie, his spouse, was the faithful godfather of Biarritz as a resort. The Villa Eugénie is no more; it was first transformed into a hotel and later destroyed by fire; but it was the first of the great battery of villas and hotels which has made Biarritz so great that the popularity of Monte Carlo is steadily waning. Biarritz threatens to become even more popular; some sixteen thousand visitors came to Biarritz in 1899, but there were thirty-odd thousand in 1903; while the permanent population has risen from two thousand, seven hundred in the days of the second empire to twelve thousand, eight hundred in 1901. The tiny railway from Bayonne to Biarritz transported half a million travellers twenty years ago, and a million and a half, or nearly that number in 1903; the rest, being millionaires, or gypsies, came in automobiles or caravans. These figures tell eloquently of the prosperity of this villégiature impériale. The great beauty of Biarritz is its setting. At Monte Carlo the setting is also beautiful, ravishingly beautiful, but the architecture, the terrace, Monaco's rock and all the rest combine to make the pleasing ensemble. At Biarritz the architecture of its casino and the great hotels is not of an epoch-making beauty, neither are they so delightfully placed. It is the surrounding stage-setting that is so lovely. Here the jagged shore line, the blue waves, the ample horizon seaward, are what make it all so charming. Biarritz as a watering-place has an all the year round clientèle; in summer the Spanish and the French, succeeded in winter by Americans, Germans, and English — with a sprinkling of Russians at all times.  BIARRITZ Biarritz, like Pau, aside from being a really delightful winter resort, where one may escape the rigours of murky November to March in London, is becoming afflicted with a bad case of la fièvre du sport. There are all kinds of sports, some of them reputable enough in their place, but the comic-opera fox-hunting which takes place at Pau and Biarritz is not one of them. It is entirely out of place in this delightful southland, and most disconcerting it is as you are strolling out from Biarritz some bright January or February morning, along the St: Jean-de-Luz road, to be brushed to one side by a cantering lot of imitation sportsmen and women from overseas, and shouted at as if you had no rights. This is bad enough, but it is worse to have to hear the talk of the cafés and hotel lounging-rooms, which is mostly to the effect that a fox was "uncovered" near the ninetieth kilometre stone on the Route d'Espagne, and the "kill" was brought off in the little chapel of the Penitents Blanc, where, for a moment, you once loitered and rested watching the blue waves of the Golfe of Gascogne roll in at your feet. It is indeed disconcerting, this eternal interpolation of inappropriate manners and customs which the grand monde of society and sport (sic) is trying to carry round with it wherever it goes. To what banal depths a jaded social world can descend to keep amused — certainly not edified — is gathered from the following description of a "gymkhana" held at Biarritz at a particularly silly period of a silly season. It was not a French affair, by the way, but gotten up by visitors. The events which attracted the greatest interest were the "Concours d'addresse," and the "pig-sticking." For the first of these, a very complicated and intricate course was laid out, over which had to be driven an automobile, and as it contained almost every obstacle and difficulty that can be conceived for a motor-car — except a police trap, the strength and quality (?) of the various cars as well as the skill (??) of the drivers, were put to a very severe test. Mr. —— was first both in "tilting at the ring" and in the "pig-sticking" contests, the latter being the best item of the show. One automobile, with that rara avis, a flying (air-inflated dummy) pig attached to it, started off, hotly pursued by another, with its owner, lance in hand, sitting beside the chauffeur. The air inflated quarry in the course of its wild career performed some curious antics which provoked roars of laughter. Of course every one was delighted and edified at this display of wit and brain power. The memory of it will probably last at Biarritz until somebody suggests an automobile race with the drivers and passengers clad in bathing suits. The gambling question at Biarritz has, in recent months, become a great one. There have been rumours that it was all to be done away with, and then again rumours that it would still continue. Finally there came the Clemenceau law, which proposed to close all public gambling-places in France, and the smaller "establishments" at Biarritz shut their doors without waiting to learn the validity of the law, but the Municipal Casino still did business at the old stand. The mayor of Biarritz has made strenuous representations to the Minister of the Interior at Paris in favour of keeping open house at the Basque watering-place, urging that the town would suffer, and Monte Carlo and San Sebastian would thrive at its expense. This is probably so, but as the matter is still in abeyance, it will be interesting to see how the situation is handled by the authorities. The picturesque "Plage des Basques" lies to the south of the town, bordered with high cliffs, which in turn are surmounted with terraces of villas. The charm of it all is incomparable. To the northwest stretches the limpid horizon of the Bay of Biscay, and to the south the snowy summits of the Pyrenees, and the adorable Bays of Saint-Jean-de-Luz and Fontarabie, while behind, and to the eastward, lies the quaint country of the Basques, and the mountain trails into Spain in all their savage hardiness. The offshore translucent waters of the Gulf of Gascony were the Sinus Aquitanicus of the ancients. A colossal rampart of rocks and sand dunes stretches all the way from the Gironde to the Bidassoa, without a harbour worthy of the name save at Bayonne and Saint-Jean-de-Luz. Here the Atlantic waves pound, in time of storm, with all the fury with which they break upon the rocky coasts of Brittany further north. Perhaps this would not be so, but for the fact that the Iberian coast to the southward runs almost at right angles with that of Gascony. As it is, while the climate is mild, Biarritz and the other cities on the coasts of the Gulf of Gascony have a fair proportion of what sailors the world over call "rough weather." The waters of the Gascon Gulf are not always angry; most frequently they are calm and blue, vivid with a translucence worthy of those of Capri, and it is that makes the "Plage de Biarritz" one of the most popular sea-bathing resorts in France to-day. It is a fashionable watering-place, but it is also, perhaps, the most beautifully disposed city to be found in all the round of the European coast line, its slightly curving slope dominated by a background terrace decorative in itself, but delightfully set off with its fringe of dwelling-houses, hotels and casinos. Ostend is superbly laid out, but it is dreary; Monte Carlo is. beautiful, but it is ultra; while Trouville is constrained and affected. Biarritz has the best features of all these. The fishers of Biarritz, living mostly in the tiny houses of the Quartier de l'Atalaye, like the Basque sailors of Bayonne and Saint-Jean-de-Luz, pursue their trade to the seas of Iceland and Spitzbergen. As a whaling-port, before Nantucket and New Bedford were discovered by white men, Biarritz was famous. A "lettre patent" of Henri IV gave a headquarters to the whalers of the old Basque seaport in the following words: "Un lieu sur la coste de la mer Oceane, qu'il se decouvre de six et set lieus, tous les navaires et barques qui entrent et sortent de la coste d'Espaiñe." A dozen miles or so south of Biarritz is Saint-Jean-de-Luz. The coquettish little city saw in olden times the marriage of Louis XIV and Marie Thérèse of Spain, one of the most brilliant episodes of the eighteenth century. In the town is still pointed out the Maison Lohabiague, a queer little angle-towered house, not in the least pretentious, where lived for a time the future queen and Anne d'Autriche as well. It is called to-day the Maison de l'Infante. There is another historic edifice here known as the Château Louis XIV, built by him as a residence for occupation "on the day of his marriage." It was a whim, doubtless, but a worthy one. St.-Jean-de-Luz has become a grand pleasure resort, and its picturesque port has little or no commercial activity save such as is induced by its being a safe port of shelter to which ships may run when battled by adverse winds and waves as they ply up and down the coasts of the Gascon Gulf. The ancient marine opulence of the port has disappeared entirely, and the famous galettes Basques, or what we would call schooners, which hunted whales and fished for cod in far-off waters in the old days, and lent a hand in marine warfare when it was on, are no more. All the waterside activity to-day is of mere offshore fishing-boats. Vauban had planned that Saint-Jean-de-Luz should become a great fortified port. Its situation and surroundings were admirably suited to such a condition, but the project was abandoned by the authorities long years since. The fishing industry of Saint-Jean-de-Luz is very important. First there is "la grande pêche," carried on offshore by several small steamers and large chaloupes, and bringing to market sardines, anchovies, tunny, roach, and dorade. Then there is "la petite pêche," which gets the shallow-bottom fish and shellfish, such as lobsters, prawns, etc. The traffic in anchovies is considerable, and is carried on by the cooperative plan, the captain or owner of the boat taking one part, the owner of the nets three parts of one quarter of the haul; and the other three-quarters of the entire produce being divided equally among the crew. Similar arrangements, on slightly varying terms, are made as to other classes of fish. Saint-Jean-de-Luz had a population of ten thousand two centuries ago; to-day it has three thousand, and most of those take in boarders, or in one way or another cater to the hordes of visitors who have made of it — or would if they could have suppressed its quiet Basque charm of colouring and character — a little Brighton. Not all is lost, but four hundred houses were razed in the mid-eighteenth century by a tempest, and the stable population began to creep away; only with recent years an influx of strangers has arrived for a week's or a month's stay to take their places-if idling butterflies of fashion or imaginary invalids can really take the place of a hard-working, industrious colony of fishermen, who thought no more of sailing away to the South Antarctic or the Banks of Newfoundland in an eighty-ton whaler than they did of seining sardines from a shallop in the Gulf of Gascony at their doors. Enormous and costly works have been done here at Saint-Jean-de-Luz since its hour of glory began with the marriage of Louis XIV with the Infanta of Spain, just after the celebrated Treaty of the Pyrenees. The ambitious Louis would have put up his equipage and all his royal train at Bayonne, but the folk of Saint-Jean would hear of nothing of the sort. The mere fact that Saint-Jean could furnish fodder for the horses, and Bayonne could not, was the inducement for the royal cortège to rest here. Because of this event, so says tradition, the king's equerries caused the great royal portal of the church to be walled up, that other royalties — and mere plebeians — might not desecrate it. History is not very ample on this point, but local legend supplies what the general chronicle ignores. On the banks of the Nivelle, in the days of Louis XIII, were celebrated shipyards which turned out ships of war of three hundred or more tons, to battle for their king against Spain. In 1627, too, Saint-Jean-de-Luz furnished fifty ships to Richelieu to break the blockade of the Ile of Ré, then being sustained by the English. One recalls here also the sad affair of the Connétable de Bourbon, his conspiracy against the king of France, and how when his treachery was discovered he fled from court, and, "accompanied by a band of gentlemen," galloped off toward the Spanish frontier. Here at Saint-Jean-de-Luz, almost at the very entrance of the easiest gateway into Spain through the Pyrenees, Bourbon was last seen straining every power and nerve to escape those who were on his trail, and every wit he possessed to secure an alliance with the Spanish on behalf of his tottering cause. "By Our Lady," said the king, "such treason is a blot upon knighthood. Bourbon a man as great as ourselves! Can he not be apprehended ere he crosses the frontier?" But no, Bourbon, for the time, was safe enough, though he met his death in Italy at the siege of Rome and his projected Spanish alliance never came off anyway. Ten or twelve kilometres beyond Saint-Jean-de-Luz is Urrugne and its clock tower. Victor Hugo rhymed it thus: "... Urrugne, Nom rauque dont le nom a la rime répugne," and his words, and the Latin inscription on its face, have served to make this little Basque village celebrated. "Vulnerant omnes, ultima necat" Travellers by diligence in the old days, passing on the "Route Royale " from France to Spain, stopped to gaze at the Horloge d'Urrugne, and took the motto as something personal, in view of the supposed dangers of travelling by road. To-day the automobilist and the traveller by train alike, rush through to Hendaye, with never a thought except as to what new form of horror the customs inspection at the frontier will bring forth. Urrugne is worth being better known, albeit it is but a dull little Basque village of a couple of thousand inhabitants, for in addition it has a country inn which is excellent of its kind, if primitive. All around is a delightful, green-grown landscape, from which, however, the vine is absent, the humidity and softness of the climate not being conducive to the growth of the grape. In some respects the country resembles Normandy, and the Basques of these parts, curiously enough, produce cider, of an infinitesimal quantity to be sure, compared to the product of Normandy or Brittany, but enough for the home consumption of those who affect it. |