| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2010 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click

Here to return to

Castles and Chateaux of Old Navarre and the Basque Provinces Content Page Return to the Previous Chapter |

(HOME)

|

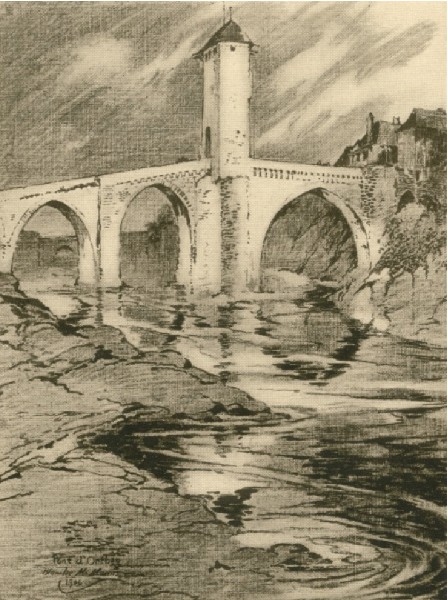

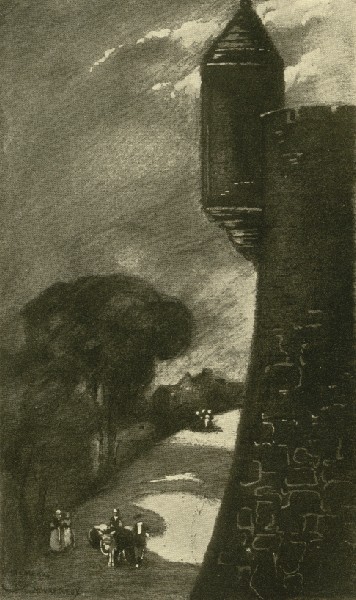

| CHAPTER XXIII

ORTHEZ AND THE GAVE D'OLORON ORTHEZ is another of those cities of the Pyrenees which does not live up to its possibilities, at least not in a commercial sense. Nevertheless, some of us find it all the more delightful for that. It is a city where the relics of the Middle Ages and the Renaissance are curiously intermingled, and if one within its walls so chose he could imagine himself as living in the past as well as in the present, and this in spite of the fact that the city has been remodelled and restored in certain quarters out of all semblance to its former self. There is little or nothing remaining of that time which Froissart described with such minuteness when writing of the court at Orthez' château. All that remains of this great pile is the Tour de Moncade, but from its grandeur and commanding site one realizes well enough that in its time it was hardly overshadowed by the better preserved edifices at Pau and Foix. At the northeast of Orthez, on a hill overlooking the city is an ancient, rectangular tower, its sides mellowed by ages, and its crest in ruins. "Savez-vous ce que sont ces ruines?" you ask of any one, and they will tell you that it is all that remains of the fine château of Gaston Phœbus. Fêtes and crimes were curiously intermingled within its walls, for always little rivulets of blood flowed in mediæval times as the accompaniment of the laughter of the feast. Gaston de Foix, after the burning of his château, came to Orthez in the thirteenth century, and began the citadel of Orthez — the "château-noble" of the chronicles of Froissart. The edifice played an important rôle in the history of Béarn. At that time Gaston was a vassal of Edward III of England who was then making a Crusade in the East. On his return he found this "château-noble" already built, and his surprise was great, for he knew not what it portended. He concluded that it could only mean the rebellion of his vassal, and he ordered the Seneschal of Gascony to demand the surrender of the property. When this was refused Edward seized it and all the domains of Béarn, and sent Gerard de Laon as envoy to put the new political machinery in running order. The envoy entered Orthez without the least obstacle being put in his way, but in an instant the gates were closed and he was made a prisoner. Irritated by this outrage, Edward, at the head of an imposing army, marched on Orthez. Gaston, seized with fear, lost his head, and made up his mind to surrender before he was attacked. No protestations of future devotion to his overlord would, however, be accepted, and Edward made him prisoner on the spot. To regain his liberty, Gaston promised to turn over the "Fortresse d 'Orthez" but, when he was set free, he established himself with a doubled garrison behind his walls and prepared for resistance. Edward pleaded for justice and honourable dealing, and a quarrel, long and animated, followed. The affair took on such proportions that the Pope sent his legate, as an intermediary, to make peace. Gaston would hear of no compromise, and called upon the king of France to take his part. A sort of council was finally arranged, during which Gaston became so exasperated that he threw his glove in the face of the English king. He begged the king's pardon afterwards, and an agreement was reached whereby everything was left as it had been before the quarrel began. Many imperishable souvenirs are left of the reign at Orthez of the brilliant Gaston de Foix, when tourneys and fêtes followed in rapid succession. It was Orthez' most brilliant epoch. It was here, to the court of Gaston Phœbus, that Messire Jehan Froissart came, in 1388, and stayed three weeks and some of his most brilliant pages relate to this visit. Of his host, the chronicler said: "De toutes choses il est si parfait." Gaston Phœbus was so powerful and magnificent a seigneur in his own right, and his castle at Orthez was such a landmark of history that Louis XI — who conceded little enough to others as a usual thing — said to his followers as he was passing through Béarnais territory on a pilgrimage: "Messeigneurs, laissez l'epée de France, nous sortons ici du royaume." Gaston Phœbus was the most accomplished seigneur of his time, and he had for his motto "Toquos-y se gaasos" — "Attack who dares." One day, in the month of August, 1390, on returning from a bear hunt, greatly fatigued, he was handed a cup from which to drink. He drank from the cup and instantly expired. Was he poisoned? That is what no one knows. It was the custom of the time to make away with one's enemies thus, and in this connection one recalls that Gaston himself killed his own son because he would not eat at table.  THE PONT D'ORTHEZ Orthez was deserted by the court for Pau, and in time the natural destruction of wind and weather, and the hand of man, stripped the château to what one sees to-day. The Pont d'Orthez is a far better preserved monument of feudal and warlike times, and it was a real defence to the city, as can be readily understood by all who view it. Its four hardy arches span the Gave as they did in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries. It was from the summit of one of the sentinel towers of this most remarkable of medieval bridges that the soldiers of Montgomery obliged the monks to throw themselves into the river below. The "Brothers of the Bridge" were a famous institution in mediæval times, and they should have been better treated than they usually were, but too frequently indeed they were massacred without having either the right or the means to defend themselves. The history of Montgomery's connection with Orthez, or more particularly the Pont d 'Orthez, reads almost as if it were legend, though indeed it is truth. The story is called by the French historians "La Chronique de la Tour des Caperas." Jeanne d'Albret, the mainstay of Protestantism in her day, wished to make Orthez the religious capital, and accordingly she built here a splendid church in which to expound the theories of Calvin and brought "professors" from Scotland and England to preach the new dogma. Orthez became at once the point of attack for those of the opposite faith, and as horrible a massacre as was ever known took place in the streets of Orthez and gave perhaps the first use of the simile that the river flowed as a river of blood. Priests and monks were the special prey of the Protestants, while they themselves were being attacked from without. One by one as they were hunted out from their hiding-places the priests and lay brothers were pushed from the parapet of the bridge into the Gave below. If any gained the banks by swimming they were prodded and stabbed by still other soldiery with lances, and from this great noyade the great Tour des Caperas became known as the Tour des Prêtres. To-day Montauban and Orthez have relatively the largest Protestant populations of any of the cities of France. The old Route Royale between Bayonne and the capital of Béarn and Navarre passed through Orthez, and the same narrow streets, irregular, badly paved, and badly kept up, are those which one traverses to-day on entering and leaving the city. One great improvement has been made in the ancient quarter of the town — though of course one does not know what historical souvenirs it may have supplanted — and that is the laying out of a mail or mall, planted on either side with great elms, and running from the banks of the Gave to the fine fifteenth-century — but still Gothic — church, well at the centre of the town. The "jambons de Bayonne" are mostly cured at Orthez, and it is indeed the leading industry of the city. The porkers of Orthez may not be corn fed, but they are well and cleanly nourished, which is more than can be said of many "domesticated pigs" in New and Old England, which are eaten with a great relish by those who have brought them up. In the religious wars Orthez played a grand rôle, and in 1814 it was the scene of one of the great struggles of France against alien invasion of her territory. Just north of the city, on the height of a flanking hill, Wellington — at the head of a force very much superior, let no one forget — inflicted a bloody defeat on Maréchal Soult. The Duc de Dalmatie lost, it is recorded, nearly four thousand men, but he wounded or killed six thousand in the same engagement. General Foy here received his fourth wound on the field of battle. Orthez is one of the really great feudal cities of the south of France. In the ninth century it was known as Orthesium, and belonged to the Vicomtes de Dax, who, only when they were conquered by Gaston III, Prince of Béarn, ceded the city to the crown of Béarn and Navarre. It was in the château of Orthez that the unfortunate Blanche of Castille, daughter of the king of Aragon, was poisoned by her sister, the wife of Gaston IV, Comte de Foix. This was one of the celebrated crimes of history, though for that matter the builder of the château, the magnificent (sic) Gaston Phœbus, committed one worthy to rank with it when he killed his brother and "propre fils" on the mere suspicion that they might some day be led to take sides against him. Orthez flourished greatly under its Protestant princes, but it waned and all but dwindled away in the unpeaceful times immediately following upon the revocation of the Edict of Nantes. The cessation of the practice of the arts of industry, and very nearly those of commerce, left the city poor and impoverished, and it is only within recent generations that it has arisen again to importance. The donjon of Moncade is all that remains of the once proud château where Gaston Phœbus held more than one brilliant court on his excursions beyond the limits of his beloved Foix. It dominates the whole region, however, and adds an accentuated note of grimness to the otherwise gay melody of the Gave as it flows down to join the Adour from the high valleys of the Pyrenees. On the opposite hillside is a memorial in honour of the brave General Foy, which will recall to some the victory of Wellington over Soult, and to others, who have not forgotten their Dumas, the fact that it was General Foy who first gave the elder Dumas his start as writer of romances. Salies de Béarn is a near neighbour of Orthez, and can be omitted from no Pyrenean itinerary. The bustling little market-town and watering-place combined dates, as to the foundation of its great industry, back to the tenth century, when the Duc de Gascogne gave to the monks of the Monastery of Saint Pé an establishment ready fitted that they might commence the industry of recovering salt from the neighbouring salt springs. All through mediæval times, and down as late as 1840, the industry was carried on under the old concession. All the distractions of a first-class watering-place may be had here to-day, and the "season" is on from May to September. The city is the birthplace of Colonel Dambourges, who became famous for his defence of Quebec against the English in 1775. At Salies is still the house which sheltered Jeanne d'Albret when she took the waters here, and not far away is the spot where died Gaston Phœbus, as he was returning from a bear hunt. These two facts taken together make of Salies hallowed historic ground. At Salies de Béarn one recalls a scrap of literary history that is interesting; Dumas père certainly got inspiration for the names of his three mousquetaire heroes from hereabouts. Not far away is Athos — which he gave to the Comte de la Fère, while Aramits and Artagnan are also near-by. In any historical light further than this they are all unimportant however. Six kilometres to the northward is the Château de Bellocq, a fine mediæval country house (fourteenth century), though unroofed to-day, the residence of Jeanne d'Albret when she sojourned in the neighbourhood. The walls, flanked with four great round towers, are admirably preserved, and the vaulting and its ribs, two square towers and a great entrance gate show the manner of building of the time with great detail. Five leagues from Orthez, on a little valley plain, watered by the Gave d'Oloron, is the tiny little city of Navarreux. Its population is scarce above a thousand, but it is the centre of affairs for twenty-five communes, containing perhaps twelve thousand souls. It is a typical, bustling, little Pyrenean metropolis, and the comings and goings on market-day at the little Hôtel de France are as good an illustration of the life and manners of a people of small affairs as one will find in a year of travel. Henri d'Albret of Navarre picked out the site of the city in the midst of this fertile plain, and planned that it should increase and multiply, if not in population, at least in prosperity, though it was at first a "private enterprise," like Richelieu's garden-city in Touraine. The preeminence of Navarreux was short lived. Henri d'Albret had built it on the squared-off, straight-street, Chicago plan, had surrounded it with walls, and even had a fortress built by Vauban, in the expectation of making it the commercial capital of the Pyrenees, but man proposes, and the lines of communication or trade disposes, and many a thought-to-be-prosperous town has finally dwindled into impotency. There was a good deal in the favour of Navarreux; its situation was central, and it was surrounded by a numerous population, but its dream was over in a couple of hundred years and the same year (1790) saw both its grandeur and its decadence. To-day it remains still a small town, tied to the end of an omnibus line which runs out from Orthez a dozen or fifteen kilometres away. The fortifications of Vauban are still there and a remarkable old city gate, called the Porte St. Antoine, a veritable gem of feudal architecture. The very dulness and disappointment of the place appeal to one hugely. One might do worse than doze away a little while here after a giddy round at Pau or Biarritz. Navarreux is of the past and lives in the past; it will never advance. As a fortress it has been unclassed, but its walls one day guarded — as a sort of last line of defence — the route from Spain via Ronçevaux and Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port. In those days it certainly occupied a proud position in intent and in reality, as its citadel sat high on a little terrace-plateau, dominated in turn by the red dome of its church still higher up. The effect is still much the same, impotent though the city walls and ramparts have become.  THE WALLS OF NAVARREUX The route into Navarreux from the south is almost a tree-shaded boulevard, and crosses the Gave on an old five-arched bridge, so narrow that one vehicle can scarcely pass, — to say nothing of two. This picturesque bridge was also the work of Henri d'Albret, the founder of the primitive city. This first foundation was a short distance from the present village. Its founder in a short time came to believe he had made a mistake, and that the bourg as it was placed would be too difficult to defend, so he tore it down in real northwest Dakota fashion, and built the present city. Louis XIV and Vauban had great plans for it, and would have done much, but Oloron in time relieved it of all pretensions to a distinction, as, in turn, Pau robbed Oloron. Between Navarreux and Sauveterre, along the Gave d'Oloron, is a whole string of little villages and hamlets whose names are scarcely ever mentioned except by the local postman. It is a winsome valley, and the signs of civilization, pale though they be, throw no ugly shadows on the landscape. Midway between these two little centres is Audaux, which possesses a vast seventeenth-century château, flanked with a series of high coiffed pavilions and great domes, like that of Valençay in Touraine. Its history is unimportant, and is rather vague, but a mere glance at its pompous ornateness is a suggestion of the great contrast between the châteaux of the north and centre of France and those of the Midi. In the north the great residential châteaux, as contrasted with the fortress-châteaux, were the more numerous; here the reverse was the case, and the feudal château, which was more or less of a fortress, predominated. The Château d'Audaux, sitting high on its own little plateau, and surrounded by great chestnut trees, is almost the peer of its class in these parts — from a grandiose architectural view point at any rate. Sauveterre, twenty kilometres from Navarreux, is one of those old-time bourgs which puts its best side forward when viewed from a distance. Really it is nothing but a grim old ruin, so far as its appeal for the pilgrim goes. Close acquaintance develops a squalor and lackadaisical air which is not in the least in keeping with that of its neighbours. It is the ensemble of its rooftops and its delightful site which gives Sauveterre almost its only charm. In the Middle Ages it was a fortified town which played a considerable part in olden history. To-day the sole evidence that it was a place of any importance is found in a single remaining arch of its old bridge, surmounted by a defending tower similar to those which guard the bridges at Orthez and Cahors, but much smaller. There is another relic still standing of Sauveterre's one-time greatness, but it is outside the town itself. The grim, square donjon of the old Château de Montréal rises on a hilltop opposite the town, and strikes the loudest note of all the superb panorama of picturesque surroundings. It was the guardian of the fate of Sauveterre in feudal times, and it is the guardian, or beacon, for travellers by road to-day as they come up or down the valley. Within the town there is, it should be mentioned, a really curious ecclesiastical monument, the thirteenth-century church, with a combination of Romanesque and Gothic construction which is remarkable; so remarkable is it that in spite of its lack of real beauty the French Government has classed it as a "Monument Historique." The sublime panorama of the Pyrenees frames the whole with such a gracious splendour that one is well-minded to take the picture for the sake of the frame. This may be said of Tarbes as well, which is a really banal great town, but which has perhaps the most delightful Pyrenean background that exists. Sauveterre is another centre for the manufacture of rope-soled espadrilles, which in Anglo-Saxon communities are used solely by bathers at the seaside, but which are really the most comfortable and long-enduring footwear ever invented, and are here, and in many other parts of France, worn by a majority of the population. Up out of the valley of the Oloron and down again into that of the Bidouze, a matter of eighteen or twenty kilometres, and one comes to Saint-Palais which formerly disputed the title of capital of French Navarre with Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port. This was because Henri d'Albret, king of Navarre, established his chancellerie here after the loss of Pamplona to Spain. Saint-Palais is what the French call a "ville mignonne." Nothing else describes it. It sits jauntily perched on a tongue of mother earth, at the juncture of the Joyeuse and the Bidouze, and its whitewashed houses, its tiled roofs and its washed-down dooryards and pavements suggest that some of its inhabitants must one day have been in Holland, a place where they pay more attention to this sort of house-cleaning than anywhere else. Saint-Palais has no historical monuments; all is as new and shining as Monte Carlo or the Digue at Ostend, but its history of long ago is important. Before 1620 it was the seat of the sovereign court of French Navarre and possessed a mint where the money of the little state was coined. The most distinctive architectural monument of Saint-Palais, the modern church and the hybrid Palais de Justice being strictly ineligible, is the fronton for the game of pelote, Saint-Palais being one of the head centres for the sport. Arthur Young, a great traveller, an agriculturist, and a writer of repute, passed this way in 1787. He made a good many true and just observations, more or less at hazard, of things French, and some others that were not so just. The following can hardly be literally true, and if true by no means proves that Jacques Bonhomme is not as good a man as his cousin John Bull, nor even that he is not as well nourished. "Chacun à son gout!" He said, writing of the operation of getting dinner at his inn: "I saw them preparing the soup, the colour of which was not inviting; ample provision of cabbage, grease and water, and about as much meat, for a score of people, as half a dozen Suffolk farmers would have eaten, and grumbled at their host for short commons." What a condemnation to be sure, and what an unmerited one! The receipt is all right, as far as it goes, but he should have added a few leeks, a couple of carrots and an onion or two, and then he would have composed a bouilli as fragrant and nourishing as the Englishman's chunks of blood-red beef he is for ever talking about. Our "agriculturist" only learned half his lesson, and could not recite it very well at that. In the midst of a great plain lying between Saint-Palais, Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port and Bayonne, perhaps fifty kilometres south of the left bank of the Adour, are the neighbouring little towns of Iholdy and Armendarits. The former is the market town of a vast, but little populated, canton, and a village as purely rustic and simple as one could possibly imagine. Iholdy and its few unpretentious little shops and its quaint unworldly little hotel caters only to a thin population of sheep and pig growers, and their wants are small, save when they go afield to Peyrehorade, St. Jean or Bayonne. One eats of the products of the country here, and enjoys them, too, even if mutton, lamb and little pig predominate. The latter may or may not be thought a delicacy, but certainly it was better here than was ever met with before by the writer of these lines; and no prejudice prevented a second helping. Armendarits, Iholdy's twin community, saw the birth of Renaud d 'Elissagory, who built what was practically the first gunboat. The birthplace of "Petit Renaud," as he was, and is still, affectionately called, the inventor of galiotes à bombes, is still inhabited and reckoned as one of the sights of these parts. |