| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2010 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click

Here to return to

Castles and Chateaux of Old Navarre and the Basque Provinces Content Page Return to the Previous Chapter |

(HOME)

|

| CHAPTER XVII

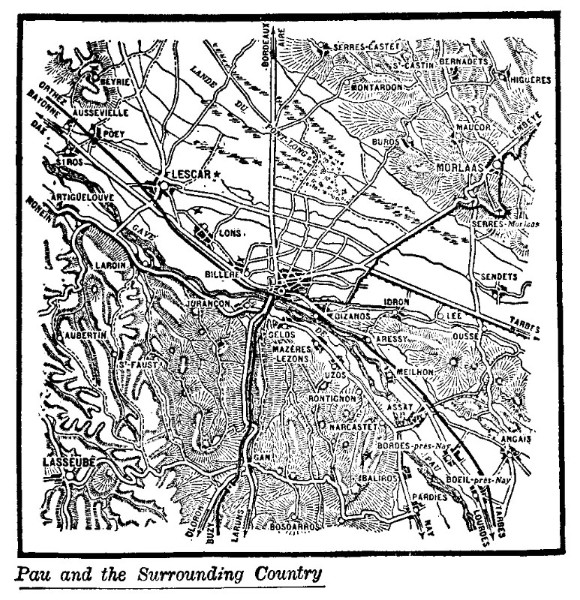

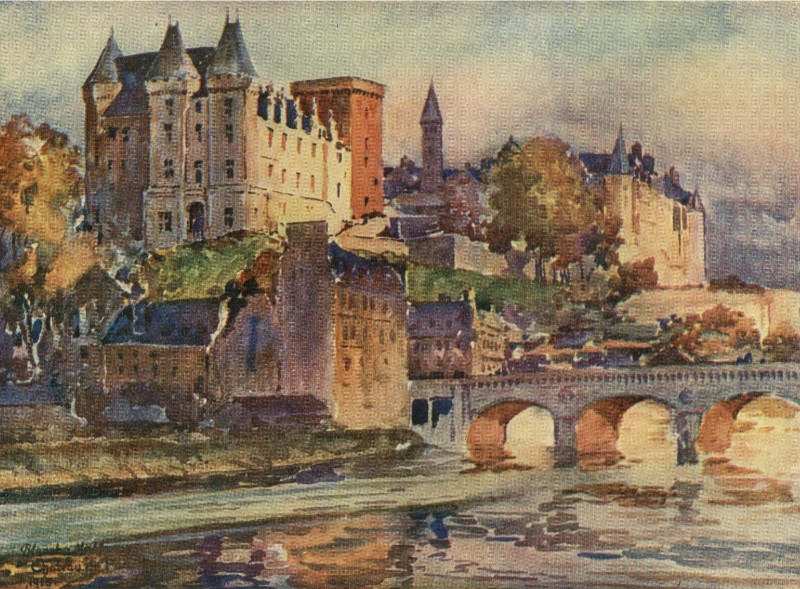

PAU AND ITS CHATEÁU  PAU AND THE SURROUNDING COUNTRY PAU, ville d'hiver mondaine et cosmopolite, is the way the railway-guides describe the ancient capital of Béarn, and it takes no profound knowledge of the subtleties of the French language to grasp the significance of the phrase. If Pau was not all this it would be delightful, but what with big hotels, golf and tennis clubs, and a pack of fox-hounds, there is little of the sanctity of romance hanging over it to-day, in spite of the existence of the old château of Henri IV's Bourbon ancestors.  ARMS OF THE CITY OF PAU The life of Pau, in every phase, is to-day ardent and strenuous, with the going and coming of automobile tourists and fox hunters, semi-invalids and what not. In the gallant days of old, when princes and their followers held sway in the ancient Béarnaise capital, it was different, quite different, and the paternal château of the D'Albrets was a great deal more a typical château of its time than it has since become. If the observation is worth anything to the reader "Pau est la petite Nice des Pyrénées." This is complimentary, or the reverse, as one happens to think. Pau's attractions are many, in spite of the fact that it has become a typical tourist resort. The château itself, even as it stands in its reconstructed form, is a pleasing enough structure, as imposingly grand as many in Touraine. This palace of kings and queens, which saw the birth of the Béarnais prince who was to reign at Paris, has been remodelled and restored, but, in spite of this, it still remains the key-note of the whole gamut of the charms of Pau, and indeed of all Béarn. The Revolution and Louis Philippe are jointly responsible for much of the garish crudity of the present arrangement of the Château de Pau. The mere fact that the edifice was a prison and a barracks from 1793 to 1808 accounts for much of the indignity thrust upon it, and of the present furnishings — always excepting that exceedingly popular tortoise-shell cradle — only the wall tapestries may be considered truly great. In spite of this, the memories of the D'Albrets, of Henri IV, of Gaston, and of the "Marguerite des Marguerites" still hang about its apartments and corridors. The Vicomte de Béarn who had the idea of transferring his capital from Morlaas to Pau was a man of taste. At the borders of his newly acquired territory he planted three pieux or pau, and this gave the name to the new city, which possessed then, as now, one of the most admirable scenic situations of France, a terrace a hundred feet or more above the Gave, with a mountain background, and a low-lying valley before. The English discovered Pau as early as 1785, fifty years before Lord Brougham discovered Cannes. It was Arthur Young, that indefatigable traveller and agriculturalist, who stood as godfather to Pau as a tourist resort, though truth to tell he was more interested in industry and turnip-growing than in the butterfly doings of "les éléments étrangers" in French watering places of to-day. Throngs of strangers come to Pau to-day, and its thirty-five thousand souls make a living from the visitors, instead of the ten thousand of a century and a quarter ago. The people of Pau, its business men at any rate, think their city is the chief in rank of the Basses-Pyrénées. Figures do not lie, however, and the local branch of the Banque de France ranks as number sixty-five in volume of business done on a list of a hundred and twenty-six, while Bayonne, the real centre of commercialism south of Bordeaux, is numbered fifteen. In population the two cities rank about the same. The real transformation of Pau into a city of pleasure is a work, however, of our own time. It was in the mid-nineteenth century that the capital of Béarn came to be widely known as a resort for semi-invalids. Just what degree of curative excellencies Pau possesses it is not for the author of this book to attempt to state, but probably it is its freedom from cold north and east winds. Otherwise the winter climate is wintry to a certain degree, and frequently damp, but an appreciable mildness is often to be noted here when the Riviera is found in the icy grip of the Rhône valley mistral. The contrast of the new and the old at Pau is greatly to be remarked. There are streets which the French describe as neuves et coquettes, and there are others grim, mossy and as dead as Pompeii, as far as present-day life and surroundings are concerned. Formerly the river Hédas, or more properly a rivulet, filled the moat of the château of the kings of Navarre, but now this is lacking. The château has long been despoiled of its furnishings of the time of Henri IV and his immediate successors. Nothing but the mere walls remain as a souvenir of those royal days. The palatial apartments have been in part destroyed, and in part restored or remodelled, and not until Napoleon III were steps taken to keep alive such of the medieval aspect as still remained. Pau, with all its charm and attraction for lovers of history and romance, has become sadly over-run of late with diversions which comport little enough with the spirit of other days. Fox-hunting, golf tournaments and all the Anglo-Saxon importations of a colony of indulgent visitors from England and America are a poor substitute for the jousting tournaments, the jeux de paume and the pageants of the days of the brave king of Navarre. Still Pau, its site and its situation, is wonderfully fine. Pau is the veritable queen of the Pyrenean cities and towns, and mingles all the elements of the super-civilization of the twentieth century with the sanctity of memories of feudal times. The Palais d'Hiver shares the architectural dignity of the city with the château, but a comparison always redounds to the credit of the latter. Below the terrace flows the Gave de Pau, and separates the verdant faubourg of Jurançon from the parent city. The sunlight is brilliant here, and the very atmosphere, whether it be winter or summer, is, as Jean Rameau puts it, like the laughter of the Béarnais, scintillating and sympathetic. The memories of the past which come from the contemplation of the really charming historical monuments of Pau and its neighbourhood are admirable, we all admit, but it is disconcerting all the same to read in the local paper, in the café, as you are taking your appetizer before dinner, that "the day was characterized with fine weather and the Pau foxhounds met this morning at the Poteau d'Escoubes, some twenty kilometres away to the north. A short run uncovered a fox in a spinny, and in time he was 'earthed' near Lascaveries!" This is not what one comes to the south of France to find, and the writer is uncompromisingly against it, not because it is fox-hunting, but because it is so entirely out of place. The early history of the city of Pau is enveloped in obscurity. Some sort of a fortified residence took shape here under Centulle IV in the ninth century, and this noble vicomte was the first to be freed of all vassalage to the Duc d'Aquitaine, and allowed the dignity of independent sovereignty. On the occasion when the Bishop Amatus of Oloron, the legate of the Pope Gregory VII, came to confer upon Centulle the title of comte, in place of that of vicomte which he had inherited from his fathers, a ceremony took place which was the forerunner of the brilliant gatherings of later days. Says the chronicler: "The drawbridge of the château lowered before the Papal Legate, and as quickly as possible he delivered himself of the mandement of the Pope, a document which meant much to the future history of Béarn." Pau owes its fame and prosperity to the building of a château here by the Béarnais princes. To shelter and protect themselves from the incursions of the Saracens a fortress-château was first built high on a plateau overlooking the valley of the Ossau. Possession was taken of the ground necessary for the site by a bargain made with the inhabitants, whereby a certain area of paced-off ground was to be given, by the original dwellers here, in return for the privilege of always being present (they and their descendants) at the sittings of the court. Just who built or planned the present Château de Pau appears to be doubtful. Of course it is not a thoroughly consistent or homogeneous work; few mediæval châteaux are. That master-builder Gaston certainly had something to do with its erection, as Froissart recounts that when this prince came to visit the Comte d'Armagnac at Tarbes he told his host that "il y a faisait édifier un moult bel chastel en la ville de Pau, au dehors la ville sur la rivière du Gave." The great tower is, as usual, credited to Gaston, and it is assuredly after his manner. Old authors nodded, and sometimes got their facts mixed, so one is not surprised to read on the authority of another chronicler of the time, the Abbé d'Expilly, that "the Château de Pau was built by Alain d'Albret during the regency of Henri II, towards 1518." Favyn, in his "Histoire de Navarre," says, "Henri II fit bastir à Pau une maison assez belle et assez forte selon l'assiette du pays." These conflicting statements quite prepare one to learn that Michaud in his "Marguerite de Valois" says that that "friend of the arts and humanity" built the "Palais de Pau." These quotations are given as showing the futility of any historian of to-day being able to give unassailable facts, even if he goes to that shelter under which so many take refuge — "original sources." One learns from observation that Pau's château, like most others of mediæval times, is made up of non-contemporaneous parts. It is probable that the original edifice served for hardly more than a country residence, and that another, built by the Vicomtes de Béarn, replaced it. This last was grand and magnificent, and with various additions is the same foundation that one sees to-day. It was in the fifteenth century that the present structure was completed, and the gathering and grouping of houses walls, all closely hugging the foot of the cliff upon which stood the château, constituted the beginnings of the present city. It was in 1464 that Gaston IV, Comte de Foix, and usurper of the throne of Navarre, established his residence at Pau, and accorded his followers, and the inhabitants of the immediate neighborhood, such privileges and concessions as had never been granted by a feudal lord before. A parlément came in time, a university an academy of letters and a mint, and Pau became the accredited capital of Béarn.  CHÂTEAU DE PAU The development of Pau's château is most interesting. It was the family residence of the reigning house of Béarn and Navarre, and the same in which Henri IV first saw light. In general outline it is simple and elegant, but a ruggedness and strength is added by the massive donjon of Gaston Phœbus, a veritable feudal pile, whereas the rest of the establishment is built on residential lines, although well fortified. Other towers also give strength and firmness to the château, and indeed do much to set off the luxurious grace of the details of the main building. On the northeast is the Tour de Montauset of the fourteenth century, and also two other mediæval towers, one at the westerly and the other at the easterly end. The Tour Neuve, by which one enters, does not belie its name. It is a completely modern work. Numerous alterations and repairs have been undertaken from time to time, but nothing drastic in a constructive sense has been attempted, and so the cour d'honneur, by which one gains access to the various apartments, remains as it always was. Within, the effect is not so happy. There are many admirable fittings and furnishings, but they have been put into place and arranged often with little regard for contemporary appropriateness. This is a pity; it shows a lack of what may be called a sense of fitness. You do not see such blunders made at Langeais on the Loire, for instance, where the owner of the splendid feudal masterpiece which saw the marriage of Anne de Bretagne with Charles VIII has caused it to be wholly furnished with contemporary pieces and decorations, or excellent copies of the period. Better good copies than bad originals! The châteaux of France, as distinct from fortified castles merely, are what the French classify as "gloires domestiques," and certainly when one looks them over, centuries after they were built, they unquestionably do outclass our ostentatious dwellings of to-day. There are some excellent Gobelin and Flemish tapestries in the Château de Pau, but they are exposed as if in a museum. Still no study of the work of the tapestry weavers would be complete without an inspection and consideration of these examples at Pau. The chief "curiosity" of the Château de Pau is the tortoise-shell cradle of Henri of Béarn. It is a curio of value if one likes to think it so, but it must have made an uncomfortable sort of a cradle, and the legend connected with the birth of this prince is surprising enough to hold one's interest of itself without the introduction of this doubtful accessory. However, the recorded historic account of the birth of Henri IV is so fantastic and quaint that even the tortoise-shell cradle may well be authentic for all we can prove to the contrary. There is a legend to the effect that Henri d'Albret, the grandfather of Henri IV, had told his daughter to sing immediately an heir was born: "pour ne pas faire un enfant pleureux et rechigné." The devoted and faithful Jeanne chanted as she was bid, and the grandfather, taking the child in his arms and holding it aloft before the people, cried: "Ma brebis a enfanté un lion." The child was then immediately given a few drops of the wine of Jurançon, grown on the hill opposite the château, to assure a temperament robust and vigorous. As every characteristic of the infant prince's after life comported well with these legendary prophecies, perhaps there is more truth in the anecdote than is usually found in mediæval traditions. Another account has it that the first nourishment the infant prince took was a "goutte" (gousse) of garlic. This was certainly strong nourishment for an infant! The wine story is easier to believe. The "Chanson Béarnais" sung by Queen Jeanne on the birth of the infant prince has become a classic in the land. As recalled the Béarnais patois opened thus: "Nostre dame deou cap deou pour, ajouda me a d'aqueste bore." In French it will be better understood: — "Notre

Dame du bout du pont,

Venez & mon aide en cette heure! Priez le Dien du ciel Qu'il me delivre vite; Qu'il me donne un garçon. Tout, jusqu'au haut des monts, vous implore. Notre Dame du bout du pont, Venez à mon aide en cette heure." It was in the little village of Billère, on the Lescar road, just outside the gates of Pau, that the infant Henri was put en nourrice. The little Prince de Viane, the name given the eldest son of the house of Navarre, was later confided to a relative, Suzanne de Bourbon, Baronne de Miossens, who lived in the mountain château of Coarraze. The education of the young prince was always an object of great solicitude to the mother, Jeanne d'Albret. For instructor he had one La Gaucherie, a man of austere manners, but of a vast erudition, profoundly religious, but doubtful in his devotion to the Pope and church of Rome. The child Henri continued his precocious career from the day when he first became a bon vivant and a connoisseur of wine. By the age of eleven he had translated the first five books of Cæsar's Commentary, and to the very end kept his literary tastes. He planned to write his mémoires to place beside those of his minister, Sully, and the work was actually begun, but his untimely death lost it to the world. Another dramatic scene of history identified with the Pau château of the D'Albrets was when Henri IV took his first armour. As he was out-growing the early years of his youth, the queen of Navarre commanded the appearance at the palace of all the governors of the allied provinces. The investiture was a romantic and imposing ceremony. The boy prince was given a suit of coat armour, a shield and a sword. A day on horseback, clad in full warrior fashion, was to be the beginning of his military education. All the world made holiday on this occasion; for three days little was done by the retainers save to sing praises and shout huzzas for their king to be. For the seigneurs and their ladies there were comedies and dances, and for all the people of Gascogne who chose to come there were great fêtes, cavalcades and open-air amusements on the plain of Pau below the castle. The culmination of the fête was on the evening of the third day. The young prince of Navarre, dressed as a simple Béarnais, with only a gold fleur-de-lis on his béret, as a mark of distinction, came out and mingled with his people. As a finishing ceremony the prince took again his sword, and, amid the shouts and acclamations of the populace, plunged it to the hilt in a tall broc, or jug, of wine, and raised it — as if in benediction — first towards the people, then towards the army, then towards the ladies of the court — as a sign of an unwritten pact that he would ever be devoted to them all. The sun fell behind the crests of the Pyrenees just as this ceremony was finished, and the youth, saluting the smiling king and queen, — his father and mother — left with his "gens d'armes pour faire le tour de sa Gascogne." The memory of Henri Quatre remains wondrous vivid in the minds of all the Béarnais, even those of the present day, and peasant and bourgeois alike still talk of "notre Henri," when recounting an anecdote or explaining the significance of some historic spot. Well, why not! Henri lived in a day when men made their mark with a firmer, surer hand, than in these days of high politics and socialistics. The Béarnais never forget that Henri, Prince de Béarn — the rough mountaineer, as he was called at Paris — was a joyous compatriot, a lover and a poet, and that he knew the joys of passion and the sorrows of suffering as well as any man of his time. The following old chanson, sung to-day in many a peasant farmhouse of Béarn proves this: — "Le

coeur blessé, les yeux en larmss,

Ce coeur ne songe qu'a vos charmes, Vous êtes mon unique amour; Près de vous je soupire, Si vous m'aimez à votre tour, J'aurai tout ce que je désire .." Under the reign of Louis XIV the inhabitants of Pau would have erected a statue in honour of the memory of the greatest of all the Béarnais — of course Henri IV — but the insistent Louis would have none of it, and told them to erect a statue to the reigning monarch or none at all. Nothing daunted the Béarnais set to work at once and an effigy of Louis XIV rose in place of Henri the mountaineer, but on the pedestal was graven these words: "A ciou qu'ils l'arrahil de nouste grand Enric." "To him who is the grandson of our great Henri." One of the great names of Pau is that of Jean de Gassion, Maréchal de France. He was born at Pau in 1609. At Rocroi the Grand Condé embraced him after the true French fashion, and vowed that it was to him that victory was due. He was full of wise saws and convictions, and proved himself one of France's great warriors. The following epigrams are worthy of ranking as high as any ever uttered: — "In war not any obstacle is insurmountable." "I have in my head and by my side all that is necessary to lead to victory." "I have much respect, but little love for the fair sex." (He died a célibataire.) "My destiny is to die a soldier." " I get not enough out of life to divide with any one." This last expression was gallant or ungallant, selfish or unselfish, according as one is able to fathom it. At any rate de Gassion was a great soldier and served in the Calvinist army of the Duc de Rohan. The following "mot" describes his character: "Will you be able to follow us?" asked de Rohan at the Battle of the Pont de Camerety in Gascogne. "What is to hinder?" demanded the future Maréchal of France, "you never go too fast for us, except in retreat." He recruited a company of French for the aid of Gustavus Adolphus in his campaign in Upper Saxony, and presented himself before that monarch on the battle field with the following words: "Sire, I come with my Frenchmen; the mention of your name has induced them to leave their homes in the Pyrenees and offer you their services...." At the battle of Leipzig (1631) Gassion and his men charged three times and covered themselves with glory. The "Histoire de Maréchal de Gassion," by the Abbé de Puré, and another by his almoner Duprat, an "Eloge de Gassion" (appearing in the eighteenth century), are most interesting reading. De Gassion it would seem was one of the chief anecdotal characters of French history. Another of the shining lights of Pau (though he was born at Gan in the suburbs) was Pierre de Marca, an antiquarian whose researches on the treasures of Béarn have made possible the writings of hundreds of his followers. He was born in Pau a few years before Henri IV, and died an Archbishop of Paris in 1689. His epitaph is a literary curiosity. "Ci-git

Monseigneur de Marca,

Que le Roi sagement marqua Pour le Prelate de son Eglise, Mais la mort qui le remarqua Et qui se plait à la surprise Tout aussitôt le demarqua." |