|

PREHISTORIC

REMAINS

AHU OR

BURIAL-PLACES

FIG. 31. STATUE

AT THE BRITISH MUSEUM.

For back of statue

see fig. 106.

FIG. 31. STATUE

AT THE BRITISH MUSEUM.

For back of statue

see fig. 106.

CHAPTER

XIII

PREHISTORIC

REMAINS

AHU OR

BURIAL-PLACES

Form of

the Easter Island Image Position and Number of the Ahu Design and

Construction of the Image Ahu Reconstruction and Transformation The

Semi-pyramid Ahu The Overthrow of the Images and Destruction of the

Ahu.

In many

places it is possible in the light of great monuments to reconstruct

the past.

In Easter Island the past is the present, it is impossible to escape

from it;

the inhabitants of to-day are less real than the men who have gone; the

shadows

of the departed builders still possess the land. Voluntarily or

involuntarily

the sojourner must hold commune with those old workers; for the whole

air

vibrates with a vast purpose and energy which has been and is no more.

What was

it? Why was it? The great works are now in ruins, of many comparatively

little

remains; but the impression infinitely exceeded anything which had been

anticipated, and every day, as the power to see increased, brought with

it a

greater sense of wonder and marvel. If we were to tell people at home

these

things," said our Sailing-master, after being shown the prostrate

images

on the great burial place of Tongariki, they would not believe us."

The

present natives take little interest in the remains. The statues are to

them

facts of every-day life in much the same way as stones or banana-trees.

Have

you no moai" (as they are termed) "in England? was asked by one boy,

in a tone in which surprise was slightly mingled with contempt; to ask

for the

history of the great works is as successful as to try to get from an

old woman

selling bootlaces at Westminster the story of Cromwell or of the

frock-coated

worthies in Parliament Square. The information given in reply to

questions is

generally wildly mythical, and any real knowledge crops up only

indirectly.

Anyone

who is able to go to the British Museum can see a typical specimen of

an Easter

Island statue, in the large image which greets the approaching visitor

from

under the portico (fig. 31). The general form is unvarying, and with

one

exception, which will be alluded to hereafter, all appear to be the

work of

skilled hands, which suggests that the design was well known and

evolved under

other conditions. It represents a half-length figure, at the bottom of

which

the hands nearly meet in front of the body. The most remarkable

features are

the ears, of which the lobe is depicted to represent a fleshy rope

(fig. 58),

while in a few cases the disc which was worn in it is also indicated

(fig. 59).

The fashion of piercing and distending the lobe of the ear is found

among

various primitive races.1 The tallest statues are over 30

feet, a

few are only 6 feet, and even smaller specimens exist. Those which

stood on the

burial-places, now to be described, are usually from 12 to 20 feet in

height,

and were surmounted with a form of hat.2

Position and Number of Ahu. In

Easter Island the problem of the disposal of the dead was solved by

neither

earth-burial nor cremation, but by means of the omnipresent stones

which were

built up to make a last resting-place for the departed. Such

burial-places are

known as "ahu," and the name will henceforth be used, for it

signifies a definite thing, or rather type of thing, for which we have

no equivalent.

They number in all some two hundred and sixty, and are principally

found near

the coast, but some thirty exist inland, sufficient to show that their

erection

on the sea-board was a matter of convenience, not of principle. With

the

exception of the great eastern and western headlands, where they are

scarce, it

is probably safe to say that, in riding round the island, it is

impossible to

go anywhere for more than a few hundred yards without coming across one

of

these abodes of the dead. They cluster most thickly on the little coves

and

their enclosing promontories, which were the principal centres of

population.

Some are two or three hundred yards away from the edge of the cliff,

others

stand on the verge; in the lower land they are but little above the

sea-level,

while on the precipitous part of the coast the ocean breaks hundreds of

feet

below.

It was

these burial-places, on which the images were then standing, which so

strongly

impressed the early voyagers and whose age and origin have remained an

unsolved

problem.

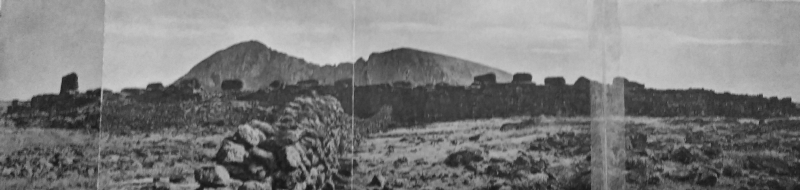

Ranu Raraku Ahu Kia-ori-ori

Ahu

Akahanga

Ahu Orpiri Ahu

Harι-o-ava

FIG. 32. AKAHANGA COVE AND NEIGHBOURING AHU

Portion of an image

still

standing

Rano Raraku, S. E.

face

Bases of fallen images

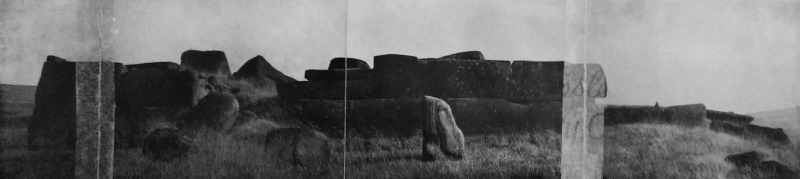

FIG. 33. AHU TONGARIKI, SEAWARD SIDE

During

the whole of our time on the island we worked on the ahu as way opened.

Those

which happened to lie near to either of our camps were naturally easy

of

access, but to reach the more distant ones, notably those on the north

shore,

involved a long expedition. Such a day began with perhaps an hour's

ride; at

noon there was an interval for luncheon, when, in hot weather, the

neighbourhood was scoured for miles to find the smallest atom of shade;

and the

day ended with a journey home of not less than two hours, during which

an

anxious eye was kept on the sinking sun. The usual method, as each ahu

was

reached, was for S. to dismount, measure it and describe it, while I

sat on my

pony and scribbled down notes; but in some manner or other every part

of the

coast was by one or both of us ridden over several times, and a written

statement made of the size, kind, condition, and name of each monument.

Unfortunately

there is in existence no large-scale plan of the coast, a need we had

to supply

as best we could; map of Easter Island there is none, only the crude

chart; the

efforts of our own surveyor were limited, by the time at his disposal,

to

making detailed plans of a few of the principal spots. The want is to

be

regretted geographically, but it does not materially affect the

archaeological

result. We were always accompanied by native guides in order to learn

local

names and traditions, and it was soon found necessary to make a point

of these

being old men; owing to the concentration of the remains of the

population in

one district, all names elsewhere, except those of the most important

places,

are speedily being forgotten. The memories of even the older men were

sometimes

shaky, and to get reasonably complete and accurate information the

whole of a

district had, in more than one case, to be gone over again with a

second

ancient who turned out to have lived in the neighbourhood in his youth

and

hence to be a better authority.

Original Design and

Construction of Image

Ahu. The burial-places

are not all of one type, nor all constructed to

carry statues; some also are known to have been built comparatively

recently,

and will therefore be described under a later section. The image ahu

are,

however, all prehistoric. They number just under a hundred, or over

one-third

of the whole.3 The figures

connected with them, of which traces still remain, were counted as 231,

but as

many are in fragments, this number is uncertain.

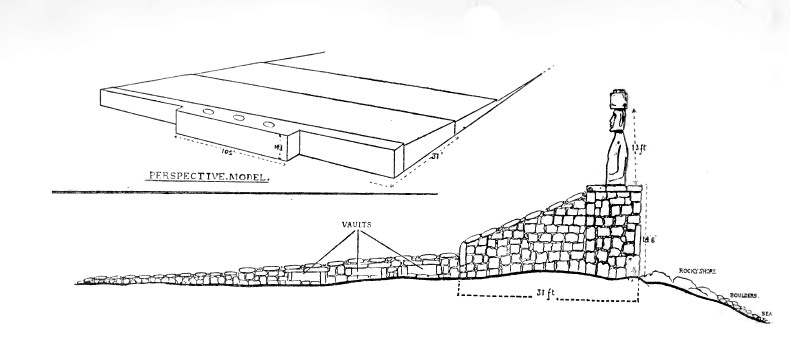

A typical

image ahu (fig. 36) is composed of a long wall running parallel with

the sea,

which, in a large specimen, is as much as 15 feet in height and 300

feet in

length; it is buttressed on the land side with a great slope of

masonry. The

wall is in three divisions. The main or central portion projects in the

form of

a terrace on which the images stood, with their backs to the sea; it is

therefore broad enough to carry their oval bed-plates; these measure up

to

about 10 feet in length by 8 feet or 9 feet in width, and are flush

with the

top of the wall. On the great ahu of Tongariki there have been fifteen

statues,

but sometimes an ahu has carried one figure only.

The wall

which forms the landward side of the terrace is continued on either

hand in a

straight line, thus adding a wing at each end of the central portion

which

stands somewhat farther back from the sea (fig. 41). Images were

sometimes

placed on the wings, but it was not usual. From this continuous wall

the

masonry slopes steeply till it reaches a containing wall, some 3 feet

high,

formed of finely wrought slabs of great size and of peculiar shape; the

workmanship put into this wall is usually the most highly finished of

any part

of the ahu. Extending inland from the foot of this low wall is a large,

raised,

and smoothly paved expanse. The upper surface of this, too, has an

appreciable

fall, or slope, inland, though it is almost horizontal, when compared

with the

glacis.

By the

method of construction of this area, vault accommodation is obtained

between

its surface pavement and the sheet of volcanic rock below, on which the

whole

rests. In the largest specimen the whole slope of masonry, measured

that is

from either the sea-wall of the wing or from the landward wall of the

terrace

to its farthest extent, is about 250 feet. Beyond this the ground is

sometimes

levelled for another 50 or 60 yards, forming a smooth sward which much

enhanced

the appearance of the ahu. In two cases the ahu is approached by a

strip of

narrow pavement formed of water-worn boulders laid flat, and bordered

with the

same kind of stone set on end; one of these pavements is 220 feet in

length by

12 feet in width, the other is somewhat smaller (fig, 93).

Head on its back Statue on its

front

Crown of

back

Portion of an image still standing

FIG. 34. AHU TONGARIKI, LANDWARD SIDE

With fifteen fallen statues.

FIG 35. AHU VINAPU

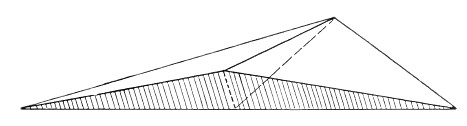

FIG. 36. DIAGRAM

OF IMAGE AHU

The

general principle on which the sea or main walls are constructed is

usually the

same, though the various ahu differ greatly in appearance: first comes

a row of

foundation blocks on which have been set upright the largest stones

that could

be found; the upper part of the wall is composed of smaller stones, and

it is

finished with a coping. The variety in effect is due to the difference

in

material used. In some cases, as at Tonga riki (fig. 33), the most

convenient

stone available has consisted of basalt which has cooled in fairly

regular

cubes, and the rows are there comparatively uniform in size; in other

instances, as at Ahu Tepeu on the west coast (fig. 37), the handiest

material

has been sheets of lava, which have hardened as strata, and when these

have

been used the first tier of the wall is composed of huge slabs up to 9

feet in

height. Irregularities in the shape and size of the big stones are

rectified by

fitting in small pieces and surmounting the shorter slabs with

additional

stones until the whole is brought to a uniform level; on the top of

this now

even tier horizontal blocks are laid, till the whole is the desired

height

(fig. 42). The amount of finish put into the work varies greatly: in

many ahu

the walls are all constructed of rough material; in others, while the

slabs are

untouched, the stones which bring them to the level and the cubes on

the top

are well wrought; in a very few instances, of which Vinapu (fig. 35) is

the

best example, the whole is composed of beautifully finished work.

Occasionally,

as at Oroi, natural outcrops of rock have been adapted to carry statues

(fig.

122).

FIG. 37. AHU

TEPEU.

Part of seaward

wall showing large slabs

some of the stones forming upper courses

are wrought foundation-stones of canoe-shaped

houses.

The study

of the ahu is simplified by the fact that they were being used in

living memory

for the purpose for which they were doubtless originally built. They

have been

termed "burial-places," but burial in its usual sense was not the

only, nor in most cases their principal, object. On death the corpse

was

wrapped in a tapa blanket and enclosed in its mattress of reeds;

fish-hooks,

chisels, and other objects were sometimes included. It was then bound

into a

bundle and carried on staves to the ahu, where it was exposed on an

oblong

framework. This consisted of four corner uprights set up in the ground,

the

upper extremities of which were Y-shaped, two transverse bars rested in

the

bifurcated ends, one at the head, the other at the foot, and on these

transverse bars were placed the extremities of the bundle which wrapped

the

corpse. The description and sketch are based on a model framework, and

a

wrapped-up figure, one of the wooden images of the island, prepared by

the

natives to amplify their verbal description.4 At times,

instead of

the four supports, two stones were used with a hole in each, into which

a

Y-shaped stick was placed (fig. 38). While the corpse remained on the

ahu the

district was marked off by the pera, or taboo, for the dead; no fishing

was

allowed near, and fires and cooking were forbidden within certain marks

the

smoke, at any rate, must be hidden or smothered with grass. Watch was

kept by

four relatives, and anyone breaking the regulations was liable to be

brained.

The mourning might last one, two, or even three years, by which time

the whole

thing had, of course, fallen to pieces. The bones were either left on

the ahu,

or collected and put into vaults of oblong shape, which were kept for

the

family, or they might be buried elsewhere. The end of the mourning was

celebrated by a great feast, after which ceremony, as one recorder

cheerfully

concluded, Pappa was finished."

FIG. 38. METHOD

OF EXPOSING THE DEAD FROM

ILLUSTRATED DESCRIPTIONS.

Looked at

from the landward side, we may, therefore, conceive an ahu as a vast

theatre

stage, of which the floor runs gradually upwards from the footlights.

The back

of the stage, which is thus the highest part, is occupied by a great

terrace,

on which are set up in line the giant images, each one well separated

from his

neighbour, and all facing the spectator. Irrespective of where he

stands he

will ever see them towering above him, clear cut out against a

turquoise sky.

In front of them are the remains of the departed. Unseen, on the

farther side

of the terrace, is the sea. The stone giants, and the faithful dead

over whom

they watch, are never without music, as countless waves launch their

strength

against the pebbled shore, showering on the figures a cloud of mist and

spray.

Reconstruction and

Transformation. Those

which have been described are ideal image ahu, but not one now remains

in its

original condition. It is by no means unusual to find, even in the

oldest parts

now existing, that is in walls erected to carry statues, pieces of

still older

images built into the stonework; in one case a whole statue has been

used as a

slab for the sea-wall, showing that alteration has taken place even

when the

cult was alive (fig. 42). Again, a considerable number of ahu, some

thirteen in

all, after being destroyed and terminating their career as

image-terraces, have

been rebuilt after the fashion of others constructed originally on a

different

plan (fig. 39). This is a type for which no name was found: it is in

form that

of a semi-pyramid, and there are between fifty and sixty on the island,

in

addition to those which have been in the first place image-ahu (fig.

42). A few

are comparatively well made, but most are very rough. They resemble a

pyramid

cut in two, so that the section forms a triangle; this triangle is the

sea-wall; the flanking buttress on the land side is made of stones, and

is

widest at che apex or highest point, gradually diminishing to the

angles or

extremities. The greatest height, in the centre, varies from about 5

feet to 12

feet, and a large specimen may extend in length from 100 feet to 160

feet. They

contain vaults. In a few instances they are ornamented by broken pieces

of

image-stone, and occasionally by a row of small cairns along the top,

which

recall the position of the statues on the image-platform; for these no

very

certain reason was forthcoming, they were varyingly reported to be

signs of pera"

or as marking the respective right of families on the ahu. As

image-terraces

may be found reconstructed as pyramid ahu, the latter form of building

must

have been carried on longer than the former, and probably till recent

times,

but there is nothing to show whether or not the earliest specimens of

pyramid

ahu are contemporary with the great works, or even earlier.

Overthrow of the Images and

Destruction of

the Ahu. The only piece

of a statue which still remains on its bed-plate is the

fragment already alluded to at Tongariki (fig. 34). In the

best-preserved

specimens the figures lie on their faces like a row of huge nine-pins;

some are

intact, but many are broken, the cleavage having generally occurred

when the

falling image has come in contact with the containing wall at the lower

level. The

curious way in which the heads have not infrequently turned a

somersault while

falling and now lie face uppermost is shown in the eighth figure from

the

western end on Tongariki ahu (fig. 34).

FIG. 39. A

SEMI-PYRAMID AHU.

FIG. 40. DIAGRAM

OF SEMI-PYRAMID AHU.

No one

now living remembers a statue standing on an ahu; and legend, though

not of a

very impressive character, has already arisen to account for the fall

of some

of them. An old man arrived, it is said, in the neighbourhood of

Tongariki, and

as he was unable to speak, he made known by means of signs that he

wished for

chicken-heads to eat; these were not forthcoming. He slept, however, in

one of

the houses there, and during the night his hosts were aroused by a

great noise,

which he gave it to be understood was made by his feet tapping against

the

stone foundations of the house. In the morning it was found that the

statues on

the great ahu had all fallen: it was the revenge of the old man. Such

lore is,

however, mixed up with more tangible statements to the effect that the

figures

were overthrown in tribal warfare by means of a rope, or by taking away

the

small stones from underneath the bed-plates, and thus causing them to

fall

forward. That the latter method had been used had been concluded

independently

by studying the remains themselves. It will be seen later, that other

statues

which have been set up in earth were deliberately dug out, and it seems

unnecessary to look, as some have done, to an earthquake to account for

their

collapse.

Moreover,

the conclusion that the images owed their fall to deliberate vandalism

during

internecine warfare is confirmed by knowledge, which still survives,

connected

with the destruction of the last one. This image stood alone on an ahu

on the

north coast, called Paro, and is the tallest known to have been put up

on a

terrace, being 32 feet in height. The events occurred just before

living

memory, and, like most stories in Easter Island, it is connected with

cannibalism.

A woman of the western clans was eaten by men of the eastern; her son

managed

to trap thirty of the enemy in a cave and consumed them in revenge; and

during

the ensuing struggle this image was thrown down (fig. 78). The oldest

man

living when we were on the island said that he was an infant at the

time; and

another, a few years younger, stated that his father as a boy helped

his

grandfather in the fight. It is not, after all, only in Easter Island

that

pleasure has been taken during war-time in destroying the architectural

treasures of the enemy.

While,

therefore, the date of the erection of the earliest image ahu is lost

in the

mists of antiquity, nor are we yet in a position to say when the

building

stopped, we can give approximately the time of the overthrow of the

images. We

know, from the accounts of the early voyagers, that the statues, or the

greater

number of them, were still in place in the eighteenth century; by the

early

part of the middle of the nineteenth century not one was standing.

FIG. 41 AHU MAHATUA, SEAWARD SIDE

Image ahu, with

east wing clearly defined.

Landward side and centre converted to semi-pyramid form.

The

destruction of the ahu has continued in more modern days. A manager,

whose

sheep had found the fresh-water springs below high water, thinking they

were

injuring themselves by drinking from the sea, erected a wall round a

large part

of the coast to keep them from it. For this wall the ahu came in of

course most

conveniently; it was run through a great number and their material used

for its

construction. One wing of Tongariki has been pulled down to form an

enclosure

for the livestock. In addition to the damage wrought by man, the ocean

is ever

encroaching: in some cases part of an ahu has already fallen into the

sea, and

more is preparing to follow; statues may be found lying on their backs

in

process of descending into the waves (fig. 43). One row of images, on

the

extreme western edge of the crater of Rano Kao, which were visible,

although

inaccessible, at the time of the visit of the U.S.A. ship Mohican

in 1886, are now lying on the shore a thousand feet below.

As the result of these various causes the burial-places of Easter

Island are,

as has been seen, all in ruins, and many are scarcely recognisable;

only their

huge stones and prostrate figures show what they must once have been.

FIG. 42. AHU

MAITAKI-TE-MOA, SEAWARD SIDE.

An Image ahu

partially destroyed and changed

to semi-pyramid type. A statue from Raraku lies in foreground; another

statue

of different stone forms part of the main wall.

FIG. 43. AHU RUNGA-VAE, ON SOUTH COAST,

UNDERMINED BY THE SEA.

Statue has fallen

backwards

1 For an

illustrated description of the method of expanding the ear, see With a Prehistoric People, the Akikuyu of

British East Africa, p. 32.

2 A full

description of the statues is given in chap. xiv.

3 This

excludes some fifteen which may have carried statues, but about which

doubt

exists.

4 The body

was no doubt supported by staves, though they were dispensed with in

the model,

being unnecessary for the wooden figure.

|