Web

and Book design, Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2008 (Return to Web Text-ures) |  (HOME) |

| THE LAKES AND

STREAMS OF MAINE THE Indian

names of

lakes, streams, and mountains in Maine are not as difficult as they

seem, being

pronounced as they are written. At our first knowledge of these names,

they

furnish not a little humorous comment. At length, however, their

pleasing

syllables become poetic, and stand for the sweet, wild districts where

they

nestle or flow, as waters, or dominate the landscape in noble

elevations. Though the

number

of the Maine lakes is legion, their total area is only sufficient to

render

them charming. A lake of great extent loses the beauty of winding

waters,

broken by many peninsulas. There seems to be a very decisive line of

opinion

drawn between those who regard these lakes as sources of power, and

those who

regard them as lures for the traveler. If the state insists, as it

easily may,

that any lands flooded shall previously be carefully cleared of timber,

there

is no reason why the beauty of Maine should not be conserved, together

with its

waters. In no case should the flooding of a timbered country be

permitted. It

can work no hardship to insist on the clearing of timber. The product

ought to

come near balancing the cost. Every one of us ought to stand strongly

against

the unnecessary ugliness of dead timbers, forlorn monuments of

carelessness or

greed, amid the slack waters formed by dams. The mountains

about

the Rangeley Lakes are not so lofty, yet afford, in conjunction with

the lakes,

scenes of noble splendor. One compares the Rangeleys with the English

lake

country. That country also we have pictured and admired. We feel that

the

Rangeley region is not a little superior in its beauty as well as in

its

extent. The Rangeley forests are more interesting. These regions must

be

considered as a unit with New Hampshire scenery. To the west of Umbagog

one is

often disappointed by the absence of pine trees near the margins of our

Maine

lakes. Whenever we do find good forest specimens they are likely to be

in a

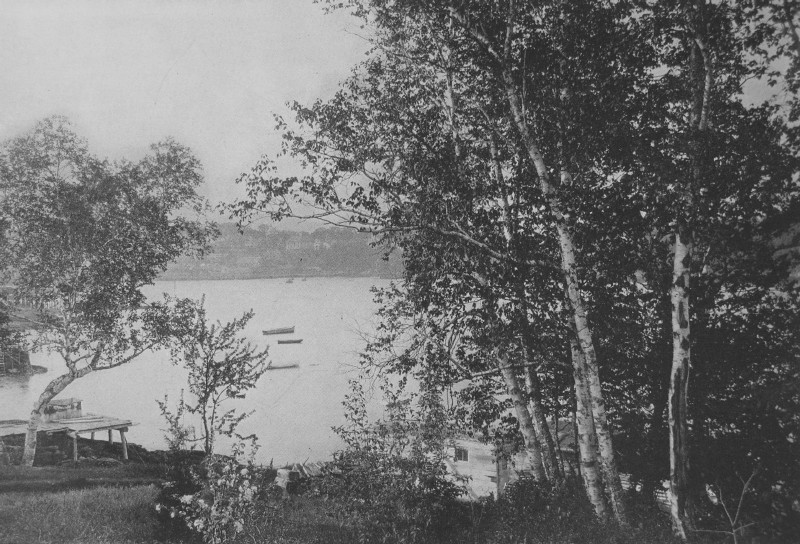

tangle, so that we may view them only in a general way. Here and there

we find

birches have been left growing on the very shores, for which they have

a strong

affection. The mountains of Maine and New Hampshire seen from Upper

Kezar Lake

in Lovell are to be commended as affording a lake setting of grandeur. About Lake

Meddybemps in Washington County, the hills, while of much beauty, do

not rise

to the dignity of mountains. The fine mountain shores about Camden and

Mount

Desert are unique in this northeastern American coast in that mountain

and sea

come together. The inlets between the mountains and Mount Desert some

one

called the only fiords in America. The statement seems to us very much

forced.

Certainly on the Pacific Coast in Puget Sound there are fiords greatly

surpassing in grandeur any of those in Norway, but it is not necessary

to look

so far away. The waterways about Wiscasset appeal to us as true fiords.

There

are other inlets on the Maine coast where swiftly-descending hills meet

deep

water. However that may be, we should not overlook one region at the

expense of

another. As one sails up the Penobscot and sees below one, opposite

Bucksport,

Mount Waldo and Treak Hill, the latter rises directly from the water's

edge. He

finds at the entrance of Marsh Bay a slope sufficiently high and rapid

to be

defined as a fiord. In fact the sail through the Penobscot in daytime

or on the

borders of morning or evening unrolls grandeurs never to be forgotten

by those

who love the hills. They are much higher and bolder than those seen on

the

Kennebec, which gains its attractions through the intimate and tender

green

slopes. The great part of the district in Maine, from somewhat west of

Augusta,

well on for one hundred and fifty miles due east, is a country just

escaping

the dignity of mountains. It is spattered over with fine hills very

often

wooded. If one would patiently and slowly thread the farm roads through

this

region he would be in a state of continual joy as one graceful contour

after

another unfolded itself. To return to

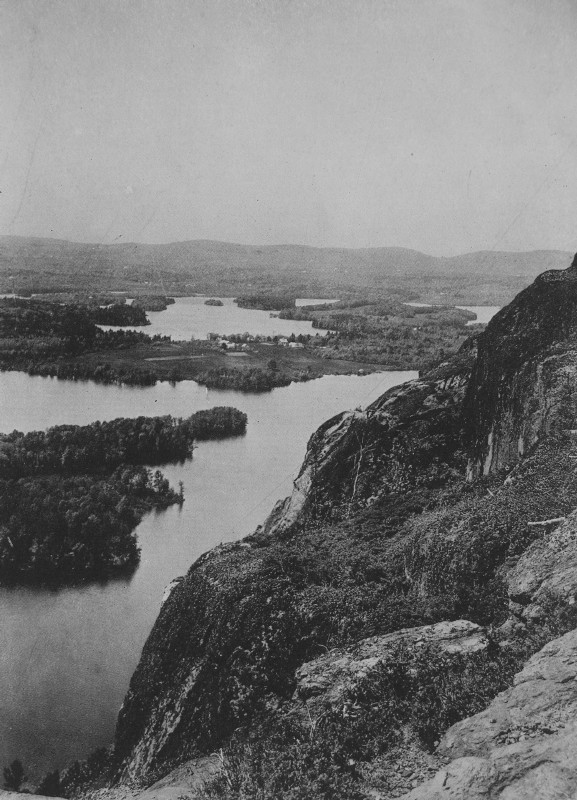

the

features of the shore and mountains, let us say that the outlook from

Maiden's

Cliff on the north side of Megunticook is of surpassing beauty, such

that we

should be at a loss to match it in our country. While the terrifying

and

majestic elevations of the Cascade Range are lacking, there is here on

Maiden's

Cliff an intimate outlining of lakes below, and, looking southeasterly

to the sea,

all together affording the highest satisfaction. We were happy in our

day's

visit to this spot. The view is well known and everywhere used in

pictorial

advertising literature. It is apparent, however, that visitors to this

point

are not as numerous as they should be. The trail is easy for a mountain

trail,

and is a climb of only twenty-five minutes even allowing for intervals

of rest.

The approach is from a farm house on the lake side, which must be

sought out by

inquiry since no signs appear. Ascending the main peak and looking

seaward, a

wholly different view is unfolded. At our feet lies Camden Harbor, and

well

easterly are the elevations of Mount Desert and northeasterly flows

along the

Penobscot River. There is a healthful, and what we hope not a too

sharp,

rivalry between Camden and Mount Desert. Each has its peculiar

beauties, and

they are sufficiently different to set off one another. The loftiness

of the

Camden Range is as impressive, viewed from the sea or from the lakes,

as any of

our eastern mountain scenery.

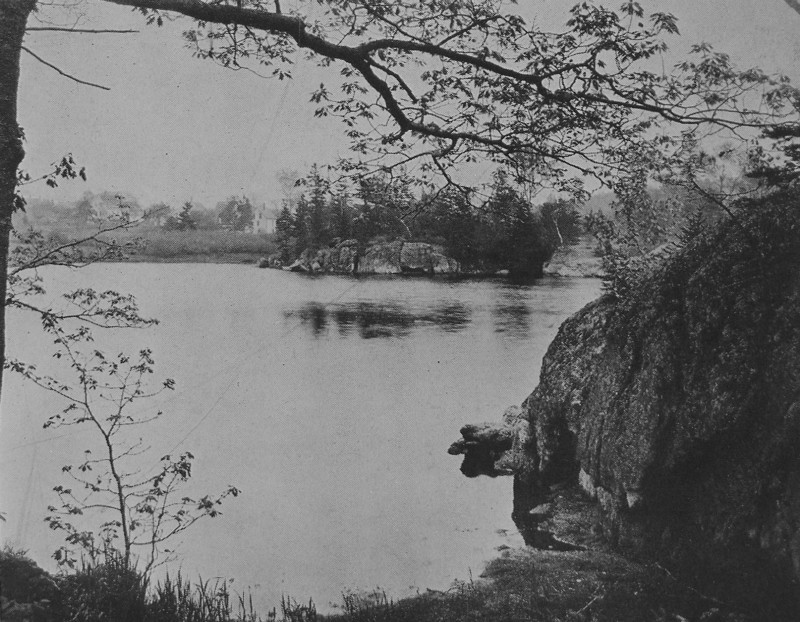

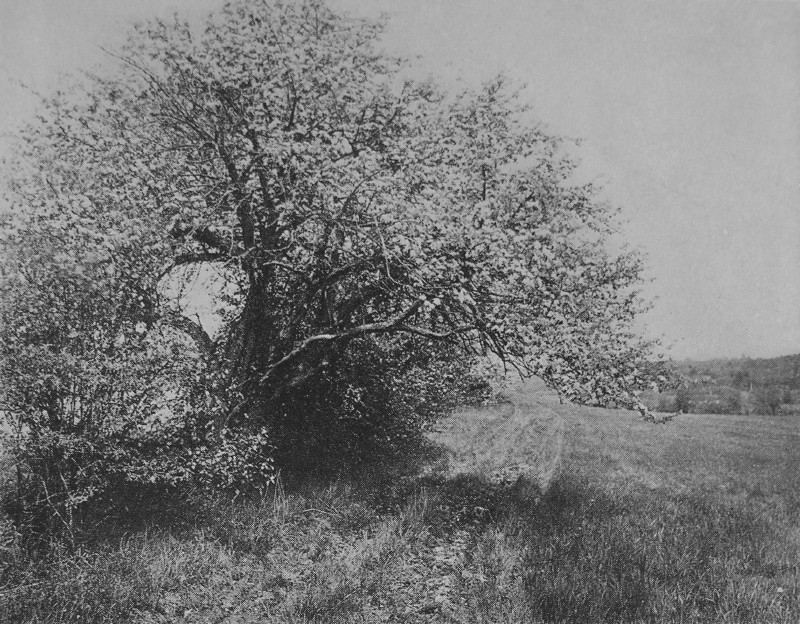

FROM MAIDEN'S CLIFF - CAMDEN  AROUND THE BLOSSOMS - WOOLWICH  A BELFAST COVE  KENNEBEC BIRCHES - HALLOWELL  A WISCASSET WATER NOOK  A GRACIOUS HEDGEROW  A MAINE FARM ENTRANCE - WOOLWICH ROAD  COTTAGE ORCHARD - BATH-WISCASSET ROAD  A HONEYMOON RETREAT - DRESDEN  A WELL SWEEP BACKGROUND - LISBON  A BLOSSOMY CURTAIN - ROCKPORT  SACO BOWS - FRYEBURG  THE OLD BARN GABLE - LOVELL

At Mount

Desert, in

the setting aside of a portion of the island known as Lafayette

National Park,

and the beginning of a road to the greatest elevation on the island, we

have a

very satisfactory undertaking and accomplishment. Happily it has not

been too

late in America to secure under national control a great many of our

country's

landscape glories. The beauty of Somes Sound and of the fine cliffs and

headlands of the various parts of Mount Desert has been rather fully

disclosed

in our travel literature. The island scene on Mount Desert that most

pleased us

was a foreground of a field of daisies beyond which lay a lake and

Mount Green.

On the Southwest Harbor shore we also found a daisy field sloping

sharply down

to the beach, with evergreens beyond. On the east shore of the island

is the

impressive cliff which is named Cathedral Rock, from the fact that an

arch

opens behind its foremost buttress. In the sea there is an endless

charm as one

wanders along the beach at low tide. We were obliged to climb down a

rugged way

since we happily came upon these cliffs at high tide. As a rule the

tide evades

us. They tell us that there are two high tides in a day, but our

experience

seems to contradict astronomy. These fine cliffs, with the water

breaking upon

them, are of course more impressive than when one walks upon the beach.

The

caves formed by the erosion of softer rocks are called The Ovens, and

are

curious massive cavities in the cliffs. Mount Desert has the peculiar

distinction of being at once the summer home of leaders in the

financial and

intellectual world. It would perhaps be a betrayal of Mount Desert to

state

that its summer mildness is hurt by occasional fogs. But who in the

reeking and

torrid July in the great city would not welcome a cool fog? The

contours of

Mount Desert are in general not so bold as those about Camden, but a

mountain

island ever holds its own fascination. This portion of Maine is without

doubt

destined to become completely occupied by seasonal dwellers. If they

prove to

have the wisdom not to tame the scenery it will be a most happy

outcome. For

ourselves we can never see the appropriateness of city lawns among the

cliffs,

rapids, and mountain streams. The vista of

Mount

Desert, as it spreads itself before a traveler on the road from

Ellsworth

eastward, and especially in Sullivan, suggests somewhat a scene in the

Greek

Isles only that our elevations are beautifully wooded. The mountain

districts

of Maine are almost always rich in lakes, and this affords more than

half their

charm. There is almost no end to the cottage sites to be found made up

of a

hill slope, below which lies a lake. We observe usually that cottages

are

huddled on the very bank of a lake, and not seldom where the highway

dust is

wafted against them. The joy of a lake is as much in looking down upon

it as in

sailing over it. Since nature has provided so many admirable hill

curvatures in

Maine it is high time that their excellence should be recognized. It often

happens

that an entrancing feature of lake scenery consists of the large and

small

islands that dot the larger lakes of Maine, from the mere breaking of

the surf

by a bold rock to the extent of many acres finely wooded. These

islands, or at

least several score of them in the Maine lakes, are still calling to

the seeker

for independence, quiet, and beauty. As seen from above, these islands

appear,

especially in a quiet day, inexpressibly beautiful. We almost fear that

the

universal use of motor-cars may prevent the development of homes upon

these islands.

Human nature, however, is not easily modified, and whatever means of

locomotion

there is in store for us, we may safely believe that an island home

will always

be attractive. Perhaps in the general development, the islands will

come into

their own again, especially since the invention of the amphibious

airplane.

BACK DOOR BLOSSOMS - DRESDEN  A COTTAGE SQUARE - LOVELL  CRYSTAL COVE - GRAY  A COUNTRY PARSONAGE - MANCHESTER  AN ABANDONED ORCHARD - MANCHESTER  ENTERING THE FOREST - NEAR WALDOBORO  THE PATH - CAMDEN OLD MAINE MILLS MAINE is the

paradise of miniature mills. There is a little valley, beloved of our

boyhood,

where a tannery and a saw mill followed one another on a stream with an

interval only sufficient for the little reservoirs between. One can

scarcely

take a half-hour's run on Maine roads without encountering one or more

such

mills or sites where they once stood. They were seldom operated the

year

through, but only at the time of high water. This time coinciding with

that in

which farm labor was least demanding, the mill was a convenient outlet

for

energy. The winter was spent in the forest preparing the logs, the

early spring

in sawing. These little water powers have lapsed into disuse, owing to

the

modern specializing in the matter of labor, so that one man does one

thing all

the time, and loses the pleasure and the development connected with

variation

of labors. What will become of the little old dams is a question that

nature is

answering for herself. Occasionally, in a rampant freshet, she gives

them a

shoulder thrust, and the freed waters of the stream babble over their

little

cascade as they have done for ages. An occasional structure of great

strength

still impounds a placid pond, on the margins of which the rushes grow. At the old

Coombs.

Mills in Augusta, on a gently shelving shore, baptisms used to occur.

This mill

has survived, and become more important than of yore. We do not connect

the

sanctifying of the waters with its prosperity. we are far from

believing that the

righteous are always well looked after on this planet. Another mill

has

been for long a source of tan-bark banking, used to protect the farm

houses in

winter. Here and there an old mill-dam has been utilized for esthetic

purposes,

to decorate the grounds of a summer place. One and another of the

better of

these ancient reservoirs has been purchased by power companies, to be

drawn

upon in seasons of drought. Some of the old dams have sunken to

puddles, owing

to the cutting away of timber. Largely, such mill ponds are anybody's

property,

in the sense that they are unused and await the coming of someone to

set them

to work again or to beautify their banks. In the olden

time

the mill was often the only lively spot in a country town, when the

farmers

were bringing in their logs or drawing away their sawed product. The

delicious

odors of the boards as they came from the saw, or the fragrance of the

yellow

meal that sifted down into the receiving tray, linger yet in our

nostrils. It was a period

of

small enterprises and slow wheels. There was no Minneapolis hum at the

old

mill-dam. At North Berwick, Ebenezer Hobb had an old water mill which

was famed

for the fine quality of the meal it turned out, but in another respect

it was

like the mills of the gods; it ground slowly, so slowly that the meal

drizzled

down in a minute stream. A farmer from afar came one day with four

bushels of

corn to grind. Ebenezer got busy. He descended to the lower regions,

and

jiggled around with the water gate. He came up and jiggled with other

controls.

At last the old wheel began to growl, like a rheumatic brute. After a

short

eternity the farmer inquired, "How you

getting along, Ebenezer?" "Oh, we're

doing pretty well. What's your hurry?" Another

interminable interval, then the farmer breaks out, "Ebenezer,

I've got an ox at home that will eat that meal faster than you can

grind

it." At that

Ebenezer

flared up, and retorted, "I'd like to

know how long he could eat it?" "He could eat

that meal," said the farmer, "till he starved to death!" CANOEING IN

MAINE IT is natural to suppose that Maine, a State of waters, would develop the finest form of the canoe. This supposition is borne out by the fact. The Indian canoe of birch bark, a rather fragile affair, has been supplanted by a canoe with close set, thin, cedar ribs, and cedar strakes, all covered by canvas. Such a canoe, twenty feet long, weighs about ninety pounds, and is ample for three people with their dunnage. More can be accommodated if necessary, but three is the right number for comfort. This canoe is not too heavy at the carries for two men, the third toting dunnage in a pack. The shape of

this

canoe is closely modeled on the lines of the Indian canoe of bark, with

a round

bottom rather flattened, and with the ends coming together in a quick,

sharp,

graceful curve. The shape is the embodiment of an Indian dream. we may

think

that the horns of the moon and the curves of the graceful birch tree,

and the

crescent beaches of the Maine lakes gave the suggestion. The result at

least is

perfection. The canoe combines more than any other human creation the

practical

and the ideal, reminding us of "the perfect woman, nobly planned."

Fur lightness, for grace, for mobility, for its perfect adaptation to

its

purpose, no device of man has ever equaled the canoe. It is the home of

the

woodsman for the greater part of the year. Even at night he draws it on

shore

and, upturning it, has a roof above him. It is his home and companion.

More

than any other inanimate thing, it is lovable and beloved. We stroke

its curves

as we pet a fine horse. It is not without good reason that the canoe

has

appealed, in picture, song, and story, to the minds of those who

discovered it

full-grown and beautiful, in the hands of the adept Indian, who evolved

it. To

be at once a thing of perfect beauty and perfect adaptability to use,

is true

of few human creations. Its very lightness and elasticity preserve it

from

harm, where a clumsier craft would be smashed. Its very resilience and

fragility make it durable. Like the human character it has the power to

rebound

after a blow, and to bob up serenely, ready for the next bump. Henry

Ward

Beecher once made a very telling simile, regarding the resilience of

the ferry

slips. An analogy based on the canoe would have supplied him with a far

more

apt and telling illustration. It is highly

significant that the old guide gains an affection for his canoe, and

thinks it,

despite all the battering it has received, better than a new one. Here

and

there a strake has been broken. Again and again the canvas has been

punctured.

Never mind. After a few deft repairs, and one more coat of new skin,

otherwise

orange shellac, the voyageur launches forth again, happier than before,

because

his own feeling and skill have entered into the craft that bears him.

It is a

monument to his ability as a boatman, and every scar is a kind of

notch-stick

history of his experiences in the rapids, from season to season. Like a

child,

none too perfect, it is the best for him because it is his. In winter

he renews

it, in the other three seasons he paddles it. It is at once his living

and his

life. It combines poetry and practicality, so that, even if he reads

with

difficulty, and has not heard of Keats, his life is nevertheless an

idyll. Maine is

especially

happy, indeed preeminent, in the range that may be covered in a canoe,

with an

occasional short carry just sufficient to emphasize the rest and

comfort of

launching again. A seat in the bottom of a canoe is a post of

observation, more

joyous and more profitable than the throne of a king. The world passes

in

review before one. The fish leap about one. The birds twitter as one

passes.

The marks on the stones show the range between high and low water. The

mosses

on the trees and the direction of the branches indicate the prevailing

winds.

The keen and experienced guide reads a long history and indulges in

sure

prophecy, as the canoe glides along. It is a story not read in history,

but

none the less worth while and delightful. The canoe has

more

to do with the development of history in America than has the

battleship. The

canoe might well be taken as the symbol and seal of Parkman's wonderful

histories. For the canoe was the pioneer of European civilization in

the west,

even more than the prairie schooner or the Conestoga wagon. When we see a

canoe, we live again our childhood with Cooper. This slight, airy

affair, begun

by the Indian, and finished by the even subtler skill of the white man,

is on

its way again to the forefront of American life. There are doubtless

more

canoes now than in the days of the Indians, and their number is

constantly and

deservedly increasing. Contrary to the supposition of the unknowing,

the canoe

is a safe craft. One may, indeed, overset it, but the finest forms and

implements used by man require delicacy of control, and when so

controlled they

are safer than more clumsy implements. It takes little practice to gain

as

great assurance of safety in a canoe as upon the land. One is far more

likely

to catch his foot in a root than to catch his keel on a rock. The use

of a

canoe encourages a certain litheness, combined with a daintiness of

touch,

which reacts upon the mind of the person who acquires these faculties,

and

gives a sense of power. One feels almost the assurance of a bird in the

sky. A

construction which is at once a vehicle and a home, which may be used

to sleep

in or under, to float in quiet water or to dash through cascades, is an

achievement into which doubtless many centuries have entered. The waters of

Maine

are competed for by the lumbermen, so that until we get into the real

backwoods, we do not have the streams to ourselves with the canoes. But

even

so, it is highly entertaining and sometimes amusing to observe the

adroitness

of the paddler in overcoming obstacles. Mr. Thornton Burgess, the

notable

naturalist and writer for children, was telling the author of his

experience

with an Indian paddler as they approached a boom. Mr. Burgess asked

what his

guide would do about that. The reply was, "When I holler, you paddle

like

——." When they neared the boom, each put his

strength to his paddle, and

the canoe gracefully mounted the obstacle like a hurdler. The writer,

in

canoeing on the Penobscot, was carried through a mass of pulp wood,

over which

the paddler, working alone, easily shot. On one occasion, when we

thought there

was no lumber near, we felt a rumbling. When we asked Roberts what it

was, he

said, "Oh, we are just on rollers." We bumped about for a long time

among sticks, some of them quite formidable, but with not half the

annoyance

caused by the mosquitoes. Upsets in rapids do occur, but they are so

rare that

every one hears about them, and the guide is always chagrined, as it is

a point

of honor with him to avoid such mishap. He fears the laugh of his

fellows more than

anything else. The guides acquire an almost uncanny skill in riding the

rough

water, and in knowing where they are safe. Of course well-known rapids

are shot

by them so often that they feel as much at home as in a parlor

— probably more

so. The delights of

the

night camp serve to perfect the experiences of a canoe trip, like a

luscious

bit of ham between sandwich slices. All the joys in life being

emphasized by

contrast, the evening is never so delightful as when it closes an

active day,

nor is the day ever so delightful as when we leave the morning camp.

All foods

are tasty, though it should be understood that the best is not

considered too

good to take along. Canoeing with a camera has marked advantages over

gunning.

One is more likely to bring home spoils, and those spoils are more

attractive

than the eyes of a dead beast. Further, in spite of the number of

cameras, it

is rare that one is used in the woods. The catch with a camera is more

likely

to be original than any catch of fish or game. Though many

indulge

in rhapsodies regarding the delights of the forest, most human beings

love a

crowd. Indeed, when among solitudes we often feel a bit selfish that we

should

have several square miles to our individual selves. A new train of

reflections

is suggested. The uninhabited parts of the earth are still very

extensive. Its

surface, if we ignore the water, which we decidedly are not doing at

the

present time, still affords some fifty acres to a family! Practically,

however,

if a man wants room, there are so many ready to resign it to him that

he may

easily acquire several square miles for the price of a diamond of

moderate

size. A certain gentleman has been adversely criticised because he

acquired an

island many miles in extent. Since no one else wanted it, we see no

reason to

object to his ambition. Some may enjoy canoeing where there are many

canoes.

Give us the wild! Let us move over the mirrored surfaces where the call

of the

moose or the loon is the only break in the celestial silence. There are

stretches

of hundreds of miles in extent in Maine, like the Allagash River trip,

during

which one scarcely sees a human being. Yet the sense of loneliness

never

descends on a true canoeist. The canoe, in

fact,

is the only available means of seeing Maine over a great part of its

extent.

Some years ago, we contributed an article on the fitting up of an old

street

car with a canoe slung in the clerestory. By negotiation the car was

taken in

tow to interesting points, and there derailed, and the canoe made use

of. Since

that time the motor car has made much more elastic a similar plan. By

carrying

a canoe thus on a specially constructed body, one may live on a motor

car with

day trips by canoe. We commend this suggestion to those who would like

to do it

first and report. It is an adventure that we propose entering upon at

the first

opportunity. When the newness of motoring passes, Americans may return

to the

water as the more pleasing and the safer recreation. The water is much

softer

to fall upon than are stone roads. Canoeing for

man

and wife, or for a tourist and his guide, offers such a variety of

attractions

that it must increase, if, indeed, the spirit of freedom still stirs in

the

blood of Americans. Three-quarters of the state of Maine is an area as

perfect

as any in existence for this incomparably attractive recreation.

Aroostook,

Piscataquis, Somerset, and Penobscot counties in the north, Washington

county

in the east, Kennebec in the center, and Cumberland and Oxford in the

West,

possibly in the order in which we have named them, offer the widest

series of

attractions. To us the streams and the small lakes are not only most

beautiful,

but in other respects most alluring. We would, however, not convey an

impression that a long or a strange trip is safe without a guide. The

very

independence and freedom of spirit which induces men to make canoe

journeys,

also sometimes induces them to venture too far and to depend wholly on

their

own wisdom. This is just as dangerous as it is to buy antiques without

advice,

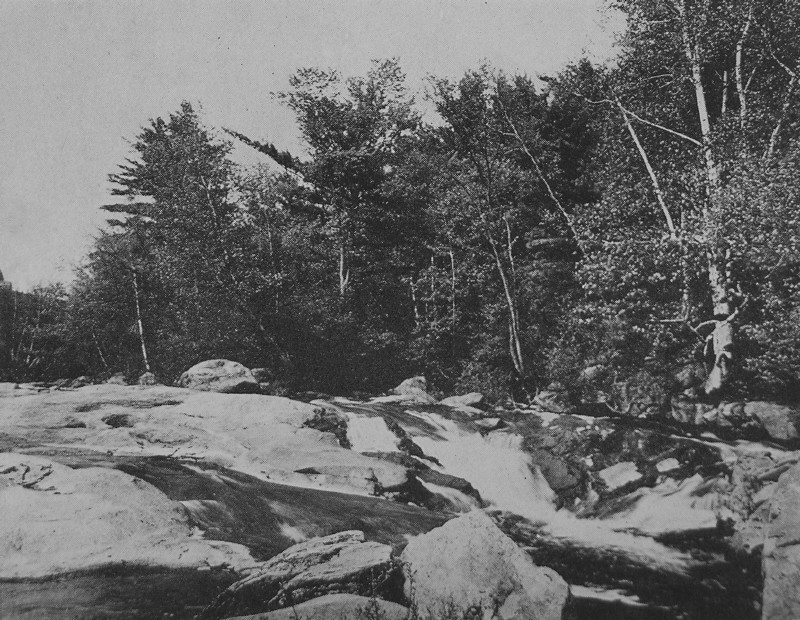

or after advice. On a canoe journey, one should frankly dispense with the usual paraphernalia of civilization, and dress precisely as a woodsman does. This remark is especially pertinent to footwear, including heavy, home-knit socks. Otherwise what might be a delightful journey may be very annoying. Those who must keep all the finical aids of the city will not enjoy a canoe journey. Beyond the comfort of a shave, and a dip in the summer streams, one should think of nothing personal.  MAINE IN SPRING - WISCASSET  GREAT ELMS OF RANDOLPH  A CAMDEN ELM ROW  SEAWARD - NORTH EDGECOMB  UNDER THE OAK BOUGH - EAST BOOTHBAY  OVER THE FIELD ROAD - DRESDEN  SWEET WATER CASCADE - WALDOBORO A great

surprise

awaited the writer, who found that in the open he could tramp three

times the

distance that he could walk in town. Dwelling beneath the sky is the

only true

elixir of youth. A trip of this sort derives additional attraction from

a

knowledge, at least in a moderate degree, of the trees and shrubs and

flowers.

The little creatures of the wood, and the game one occasionally comes

upon,

increase our pleasure. One confession,

however, we have to make, humiliating though it be. Always in country

journeys

we take a stock of blank paper, to enroll the thoughts that rush upon

us.

Always all the paper is brought back as blank as at the beginning. The

rushing

thoughts are drowned or blown away! They seem very important at the

time, but

while a black fly is crawling through one's hair, or the glory of a

summer

cloud is overhead, how can one stop to write? Except to a few geniuses

like

Thoreau, whose memory was perhaps phenomenal, the woods are not

productive of

literary achievement. Even artists in oil, if the truth is to be blazed

abroad,

frequently whisk away, when there is a knock at the door, the

photographs of

the scenes they are "painting from nature." |