CHAPTER II

THE rabbit skin was very

light and warm and soft. Jimmy snuggled down in it, and half dreamily

watched

the banks of the river slip past. The tea had made him sleepy. He saw

the Magic

Forest through a haze, and the great trees and the little trooped by

solemnly

like an army with banners. Before him the lithe bowsman swung his

paddle tirelessly.

The whispering swish swish

of the water lulled him. At this early moment

in a strange adventure little Jimmy might have fallen sound asleep had

not a

diversion aroused him

.

The leading canoe suddenly

stopped short, worked noiselessly sideways, and came to rest against

the bank.

The other canoes joined it. No

word was

spoken, and Jimmy was warned by an expressive gesture to keep silent.

After a

moment Ah-kik, the bowsman, drew from a long greasy case a musket bound

in

brass. The canoe crept forward around the bend.

Not a drip of water broke

the absolute stillness. Makwa, although Jimmy could not see him, was

still

paddling without raising the paddle from the water, and indeed with a

barely perceptible

motion of the wrists. To the little boy's imagination the craft seemed

suddenly

to take the character of a wind vane he had watched from his windows,

turning

to right, to left, swimming across the cloud-strewn ether as though

guided by a

will of its own.

Something exciting was going

on. He did not know what it was, but his eyes grew large and bright,

and he

held himself so still as hardly to breathe. Now it became evident that

the

canoe was quietly but steadily approaching a certain point on the shore

where a

little sandy beach and a grass plot interposed between the

forest and the

river. A broad maple tree rose just outside the edge of the woods,

under which

lay a deep shadow backed by the dusk of the forest. Nearer and nearer

the canoe

crept. And then suddenly, as though it had been evoked by the wave of a

magician's wand, Jimmy saw that the deep maple shadow had a living

tenant.

And even then he could not

realize that he looked on a deer. This had the graceful shape of the

creature,

to be sure, but it was so exactly the color of the maple shadow that it

seemed

to be the unsubstantial ghost of a deer, as though one could

see through it as

through a clouded glass.

The excitement in Jimmy's

little breast was intense. His heart thumped, his breath caught in his

throat,

and in spite of his best efforts he trembled all over as though with a

violent

chill. Each moment he expected to see the deer run away. But still the

canoe

slipped silently forward as idly as a leaf wafted thither by the wind.

Then all

at once, when the prow was actually within a few feet of the bank,

Jimmy was

conscious of a violent trembling. Makwa had thrust his paddle down to

stop the

headway. Ah-kik, still unobtrusively, without abrupt motions, raised

the

brass-bound musket.

A sudden roar broke forth, a

cloud of white smoke enveloped the bow, the canoe leaped

backward

like a spirited horse.

Makwa dropped the paddle

aboard with a clatter and stretched his arms. Ah-kik called back

something in

his natural voice. From around the bend streamed a flotilla of canoes.

The

everyday sounds after the period of strained silence and patient

endeavor

seemed almost profane.

Jimmy leaped ashore with his

companions, fully prepared to exult over a dead deer. What was his

disappointment

to discover only four deep, sharp footprints where the

animal

had leaped. Evidently the shot had

failed.

But Jimmy had still a long

way to go before the rudiments of his woodcraft should be complete. He

did not

know that Ah-kik could tell by the way the deer carried its tail

whether or not

the animal was wounded, and how badly. And so he was much surprised

when two of

the young men returned after some minutes carrying the venison.

In the bustle of making camp

Jimmy was for some time unnoticed. Certain of the men cut up dry wood.

Old

women swiftly built little fires of birch, touchwood, bark, and twigs.

Even the

little children busily collected and carried in the wood chopped by the

men.

The deer was quickly skinned and cut up. Pots bubbled and steamed over

little

fires. Dogs yelped with delight as bits of offal were tossed them.

Then when the first tasks

were over, he was surrounded. The younger children

stared at him wide-eyed,

the older teased him; but as he did not

understand what they

said, this did

not worry him in the least. One handsome little fellow

slightly older than

himself smiled at him, and when Jimmy smiled back, he promptly drove

the others

away. Then he squatted on his heels at Jimmy's

side.

"Minne-qúa-gun,"

said he, picking up a tin cup. And so Jimmy learned his

first Indian word.

In this was a new and

delightful

occupation. To speak real Indian words was an accomplishment

Jimmy would have

reverenced in another. And here was a chance to

learn for himself. He

memorized tschimon,

the canoe; and ah-boo-é,

the paddle; and ah-gáh-quit,

the axe. Then he resolved to

find out something useful to himself. He

hugged his arms close about his chest, shivered violently, and looked

inquiringly toward his companion.

"Kss ina," said

the latter at once.

Jimmy immediately ran to old

Makwa, who was smoking a pipe on a fallen tree.

"Kss

ina," said he, pointing to his thin

night-dress and his bare shins. "Kss ina, kss ina!"

Makwa laughed, his fine old

face wrinkling in a hundred deep little lines. He called

sharply. An old woman

came forward. Makwa spoke a few words to her, whereupon she went away

for some

moments, only to return bearing a bundle wrapped in canvas which she

laid at

Makwa's feet.

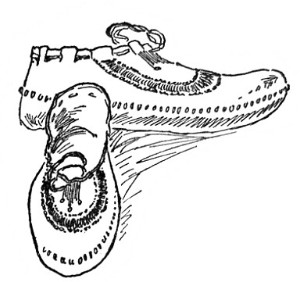

The bundle when opened was

found to contain a variety of things. Makwa picked out a little

deerskin shirt,

a pair of blue leggings made of stroud, two squares of blanketlike

material

called duffel, and a pair of deerskin moccasins.

The

squares he wrapped about Jimmy's feet in place of socks, the

leggings he bound with a pair of heavily beaded garters,

the

deerskin shirt he slipped on deftly, and

fastened with a worsted sash. When arrayed in them, the little boy was

too

happy to sit still.

But now the meal was cooked,

Jimmy discovered that he was very hungry. He sat

with a group of women

and children, and accepted thankfully his share of venison, fish, and

tea. A

little girl sat next to him, a pretty little brown thing with big, soft

eyes.

She gazed at him solemnly during the meal.

At last he nodded and smiled

at her, whereupon she showed all her teeth in the prettiest fashion in

the world.

Jimmy, with a full stomach, began to feel very contented. The sun was

warm, the

people about him looked on him kindly, this open-air meal under the

greenwood

tree was inexpressibly thrilling to his young imagination.

That

afternoon he was given a short paddle and set

to work. Nor was the paddling a matter of play merely. When his

unaccustomed

little wrists and shoulders became very tired, old Makwa sternly

forbade him to

rest. He was compelled to keep on, although his arms at times seemed

ready to

drop off, and his efforts could certainly have added little to the

speed of the

canoe. However, twice the party disembarked on the beach, drew the

canoes up,

unloaded all they contained, and set off through the forest, carrying

packs.

Here, too, Jimmy was given his share to carry, and his thin moccasins

were

slight protection to his feet, which speedily became bruised and wet.

However,

the life and mystery so filled Jimmy's mind that he only partly noticed

these

things.

Of course the trees were

still bare of leaves, but the spring was awakening. All sorts of noises

sounded

through the woods. Jimmy did not know what they were, but little by

little he

learned from Taw-kwo, the young boy.

"Bump! bump! bump!

bump! br-br-rr-r!"

boomed a hollow wooden note.

"Penáy,"

said

Taw-kwo. Some

days later a partridge

was flushed into a tree. "Pe-náy," said

Taw-kwo again, and so

Jimmy knew that penáy was a large bird

with a fan-tail

whose capture was most desirable, and who made remarkably good eating.

But he

did not know the English name for it.

In this fashion he acquired

much information about the woods which he would have found

quite valueless in

the towns, for the simple reason that he would have been unable to tell

any one

about it. The hawk, the rabbit, the squirrel, the muskrat, the jay, and

many

others he learned thus. Of course he could not always

remember, but Taw-kwo

was patient in repeating, and Jimmy was just of the age to learn

quickly by

absorption.

On the way

back through the

woods for a second load on the second carry, Jimmy saw his first live

porcupine. The beast was scornful and

lordly, and disinclined to hurry in the least, after the manner of

porcupines

everywhere, but to Jimmy a wild animal of this size which would permit

itself

to be approached, was a brand-new experience. Of course he wanted to

kill it.

That is invariably the first instinct. But May-may-gwan, the soft-eyed

little

girl, would not allow him to do so. Jimmy learned thus his lesson in

woods

moderation, for the woods Indian never kills wastefully.

scornful and

lordly, and disinclined to hurry in the least, after the manner of

porcupines

everywhere, but to Jimmy a wild animal of this size which would permit

itself

to be approached, was a brand-new experience. Of course he wanted to

kill it.

That is invariably the first instinct. But May-may-gwan, the soft-eyed

little

girl, would not allow him to do so. Jimmy learned thus his lesson in

woods

moderation, for the woods Indian never kills wastefully.

The rest of the afternoon

the canoes floated down the river. The shores glided by silently. Jimmy

many

times forgot the ache of his shoulders in the excitement of a swiftly

vanishing

wing, the mysterious withdrawal of some brown spot that, in

this manner only,

proclaimed itself a forest creature. Once a mink bobbed up for a moment

on a

piece of driftwood, and paused, its forefeet under its chin,

to stare

malevolently at them as they glided by. Often the muskrats would be

seen

swimming in arrow-shaped ripples.

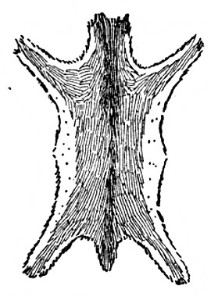

Once a

slim, graceful animal

of some size slipped from a rock ledge ahead. This the Indians thought

important enough to discuss, gathering their canoes into one idly

drifting

bunch. For it was nigig, the otter,

and the value of his pelt in the winter won him consideration

as a personage.

Often squirrels crossed the river, steering themselves with their bushy

tails.

Makwa, noting the interest of the boy, good-naturedly extended his

paddle to

one of the little animals, whereupon, to Jimmy's vast delight, it

scrambled up

the paddle to the gunwale within two feet of his hand, where it sat

resting for

a moment, and then plunged into the water again.

About the middle of the

afternoon the women's canoes were permitted to go ahead for the purpose

of

making camp, so that by the time the sun was low the men were enabled

to draw

ashore for the night. A number of little birch-bark shelters were

already in

place, the tiny fires were winking bravely, the dogs were

squatted in a

semicircle just at the edge of the brush

awaiting their share

of the

meal.

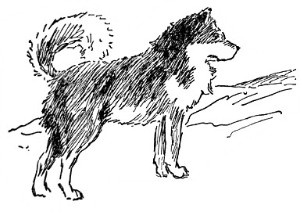

Jimmy thought he had never

seen such funny dogs. Their noses and

ears were pointed, their hair long and thick, and their tails as furry

as a

fox's brush. He tried to make friends with them, but they snarled at

him so

savagely that he drew back alarmed. In after days he succeeded in

knowing them

better, but now they were distrustful. They were

more

than half wolf, with the wolf's fierce instincts.

But now Taw-kwo

touched him

on the shoulder, smiling and motioning him to follow. He did so. The

two boys

picked their way through the brush to the mouth of a little creek

flowing into

the river. There Taw-kwo unrolled a finemeshed net he was

carrying, fastened

one end to a staff which he braced upright in the bottom, waded across

and

stuck the other end in a similar manner, so that the mouth of the creek

was

entirely closed by the net. Taw-kwo did not seem to mind in the least

wading in

the cold water with his moccasins and leggings on. "Kee-gawns," said

he, making with his hand the motion of a fish swimming.

He

touched his finger to his lips to enjoin caution.

Stealthily he lay on his stomach and crawled to the sharp edge of the

bank.

Jimmy followed his example and peeped over. Below his eye ran five or

six grooves

through the thick water-mud which ended in a regular gallery

of holes. And

just as Jimmy looked, some bright-eyed, solemn, whiskered animal seemed

to fade

into hiding. "She-shesk,"1

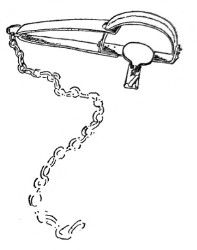

whispered Taw-kwo. He signed

to Jimmy to remain, and returned shortly

carrying two steel traps. These he set

at the mouths

of the grooves, covering them craftily with mud, and touching none of

the

surroundings with his hands.

At camp by this time the evening

meal was

prepared. Jimmy had never been so hungry, in his life. He ate and ate

until he

could not cram down another mouthful, and he was almost too lazy to

move over

to the larger fire, or to hang up before the blaze his moccasins and

duffels as

did the others. The flames leaped, making shadows on the Magic Forest.

Over in

its depths a night-bird began to moan whip-poor-will. The dogs

sat on their

haunches blinking their eyes. Men smoked and laughed and talked. Women

conversed in low voices.

Little May-may-gwan

sat beside him and held his hand.

After a long time Taw-kwo led him

to

a

shelter in which was spread six inches of balsam browse. The Indian boy

laid

out the rabbit-skin robe. The balsam smelled good to Jimmy. His eyes

grew

heavier and heavier.

But he was not to sleep yet.

Suddenly a tremendous row brought him to his feet. The dogs were

clamoring,

excited figures were running past the firelight. Jimmy instinctively

thrust his

feet into his moccasins and followed.

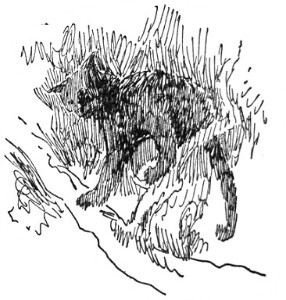

Down

through the tangled

forest the chase went pell-mell, the dogs always in the lead. Some of

the Indians

had snatched up torches. Stumbling, shouting, clambering, breathless,

the

multitude streamed through the silent dark. Then it bunched at a slim

tree

about which the dogs were leaping frantically. Jimmy could

distinguish a

fierce-eyed dark animal, about the size of a dog, crouched in the

branches. The

little boy was still half asleep.

What

followed was much confused. Something dislodged the

lodged

the beast. It fell among the dogs. Immediately there was

a great fight, in which the Indians seemed to be trying desperately to

deliver

a telling blow. Then it was all over. Two of the dogs were dead; from

others

blood was streaming. One of the Indians was tying a bandage

around the calf of

his leg.

Back

through the ancient forest filed the convoy with

its prey. At the fireside Jimmy saw that the beast was powerful, blunt

nosed,

with long claws, "Swingwadge," replied Makwa to his look of

inquiry.

Many years after Jimmy again saw one of them stuffed at the Sportsman's

Show,

and so knew that he had assisted at the killing of a carcajou, the

fiercest

fighting animal for its size in America. And thus closed what he always

thought

of afterward as his Wonderful Day.

____________________

1

Muskrat.

Click the

book image to turn

to the next Chapter.

Click the

book image to turn

to the next Chapter.

|