| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2009 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

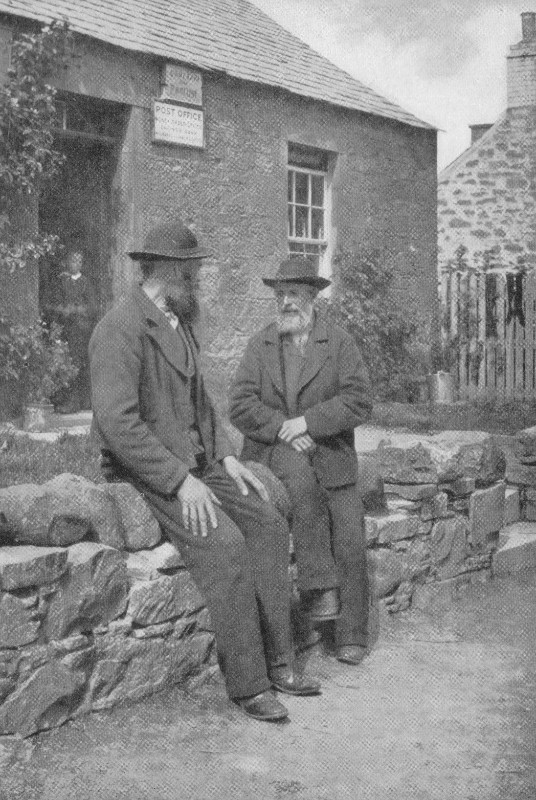

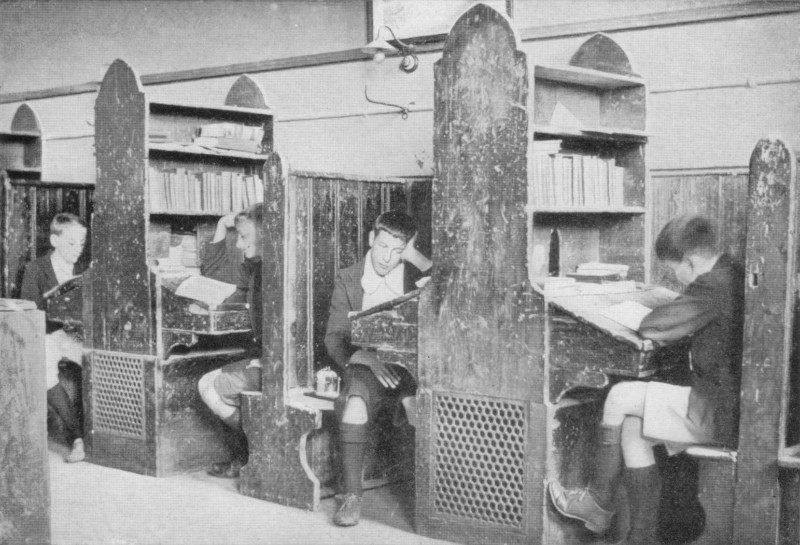

The

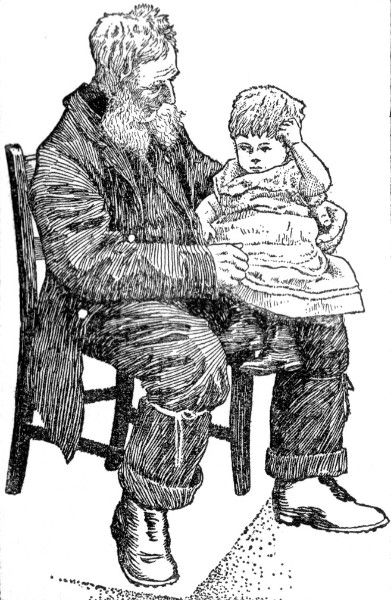

Land of Heather I A RURAL HAMLET  His Favorite Grandchild

IN southern England the hawthorn hedges had shed their petals and taken on their summer greenness; but when I continued northward and crossed the vague boundary line which separates the two ancient kingdoms of the island, the hawthorn was in full bloom. This was reassuring, for I had been half afraid I was too late to see the Scotch spring at its best; and the unexpectedness of the transition made these northern hedgerows, with their white flower-clusters and their delicate emerald leafage, seem doubly beautiful. That I might lose nothing of Nature's charm in its early unfoldings of buds and greenery, I did not pause in any of the large towns, but kept on until I reached the secluded hamlet of Drumtochty, among the hills a few miles beyond Perth. There I made my home for several weeks in the cottage of the village shoemaker. A wide-spreading farm and grazing district lay round about, and the Highlands were not far distant. Indeed, their outlying bulwarks were always in sight, rising in blue ridges that cut ragged lines into the sky along the north. Drumtochty, or "the clachan," as it was familiarly called by the natives, was the central village of the region. It was situated on a long slope, or "strath," that swept gently downward to where a sudden declivity marked the verge of a winding, half-wooded ravine, in the depths of which flowed a small river. Aside from the clachan on the strath, habitations were much scattered. They consisted mostly of neighborless farmhouses, and a few lonely shepherds' cottages on the borders of the moors. In the midst of an imposing grove a mile or two from the village stood the big decayed mansion of Logie House, reminiscent of days not very remote, when the district had its own local lairds; but at present resident gentry were entirely lacking. There was, however, a shooting-lodge, at the head of a wild ravine up toward the hills, to which the aristocracy resorted in the season; and I ought to mention Trinity College, on a high terrace, in plain sight from the clachan, just over the river, its brown walls and pinnacles rising above its environing trees, like some ancient castle. The college clock could be plainly heard when. it tolled the hours, and the college bells made pleasant music chiming for evening service. But it was only by sight and sound that Trinity College had any connection with the life of the people who dwelt in its vicinity; for while they were strenuous Presbyterians, the school was strictly Episcopal, and the pupils all came from a distance.  Threshold Gossip The low stone houses of the clachan were built in two parallel lines. One row fronted on the east and west highway. The other was behind the first, up the hill a few rods. The homes on the foremost row were just enough removed from the road to give space before each for a narrow plot of earth that the householders dug over with every return of spring and set out to flowers. Rose bushes in abundance clambered up about the windows and doorways, and several of the cottages had a pair of ornamental yew trees so trimmed and trained as to arch the gate in the stone wall or picket fence which separated the flower-plots from the street. The people took great pride in their dooryard plants, and in all such adjuncts of the house-fronts as were constantly in the eyes of the critical public. The flowers were more especially the care of the women, but it was not uncommon to find the children and the men working among them; and there was "Auld Robbie Rober'son," now over eighty and living all alone, who kept the flower-beds that bordered his front walk as tidy as anybody. I stopped to speak with Auld Robbie one day while he was in his garden, pulling some grass out of a bunch of columbines — "Auld ladies' mutches" (caps), he called them. He was glad to tell me about his plants and blossoms, and when I started to go he picked a rose and presented it to me, first carefully removing all the leaves from the stem, that its beauty might be the more apparent. The houses on the back row of the clachan were but little exposed to public view, and the approaches to them were often carelessly unkempt. The neat paths and flower-beds characteristic of the fronts of the more prominent row were here lacking. Grime and disorder had their own way. Perhaps this was because these houses had no back doors; for their rear walls bordered a little lane and were wholly blank, save for now and then a diminutive window. Some place for tubs, old rags, and rubbish was a necessity, and as the front door was the only entrance, odds and ends naturally gathered there. Between the two rows of houses the land was checkered with little square gardens, and I found these at the time of my arrival crowded full of green, newly started vegetables. In some convenient nook of the gardens, next the hedges that enclosed them, was often a hive or two of bees. It was swarming-time, and almost any warm midday an incipient migration was liable to be discovered. Immediately arose a great commotion of noise and shoutings intended to distract the bees; and there was an excited running hither and thither to borrow a hive and get a certain ancient of the village, who was a bee expert, to help settle the swarm in its new home. This bee expert, who was commonly spoken of as "The Auld Lad," comes hobbling into the garden where the bees, supposedly by virtue of the racket made, have delayed their flight and suspended themselves in a brown branch on a gooseberry bush or some other garden shrub. All the women and children of the vicinity gather at a safe distance and look on while the Auld Lad with apparent unconcern sets some stools covered with white cloths near the swarm. Then he puts the hive on the cloths and brushes the bees into it as if they were so much chaff. His face is unprotected and his hands bare, and the crowd regard him as a sort of wizard in his dealings with the hot-handed insects; but he says it is nothing — bees do not care to sting at such a time. Drumtochty had two shops. Each occupied one room in the owner's dwelling. The post-office was in the larger shop, but about all that was needful for official purposes was a desk, as the mail was delivered at the houses twice a day. Any community in Britain that receives an average of fifty letters a week is entitled to free delivery, and the people of the Drumtochty district were not so few or seclusive but that they did much more postal business than this minimum. The chief daily mail arrived at twelve, when a stout, heavy-shoed man in uniform would come tramping in from the west with a brown bag strapped over his shoulder and a cane in his hand. He enters the post-office and the mail is emptied from his bag and sorted on the little counter. The postmaster and all his family join in this task, and it is soon finished, and "Posty" with a new load goes trudging in his steady swing down the road. At the same time the postmaster's daughter shoulders a smaller bag, dons her straw hat, and starts out to distribute the mail through the clachan and for a mile and a half west among the farmers. The sign over the door of the second of the village shops read thus: "R. Wallace, General Grocer, licensed to sell tea, tobacco, and snuff." The room in which these articles, together with "sweeties" and other small wares, were sold was tiny and much crowded. Near the door was a little counter with a pair of scales on it, and behind this counter presided Mrs. Wallace, the proprietor of the shop. She was a short, uneasy-looking body with a sharp tongue, and a long story of trials and wrongs and complaints which she retailed with the goods from her shelves to every customer. She had a remarkable propensity for keeping in hostilities with her neighbors, but always felt herself to be the innocent and injured party; and to any person who would listen she discoursed endlessly on others' blackness and her own immaculateness. In fact, these wordy outpourings made it so difficult for a customer to get away that many of the villagers avoided her shop altogether.  A Favorite Loitering Place Until within a few years she and her husband had kept the village inn. They were turned out, according to her story, through a very wicked series of plottings, deceptions, and broken promises. Her husband's brothers were the chief villains in the affair, and it was understood that she lay awake nights hating them. The two dissenting ministers of the village were also objects of her antipathy. Both in preaching and in practice they were opposed to the use of spirits as a beverage, and the things they had said about those who sold intoxicants were not at all to the liking of the lady of the shop. "They're a'ways meddlin'," she declared in tones full of venom, "and they'll preclaim frae the poopit aboot the weekedness o' the public (the grog shop); but I say, dinna they ken that in the Bible the publicans are aye ca'ed much better than the sinners?" The public house of the clachan was on the back row. At noon, in the evening, and on holidays, there were many loiterers in its neighborhood, and the sound of boisterous laughing or singing was often heard from the taproom. Occasionally the merriment was increased and encouraged by the drone of a bagpipe. The inn stood near a narrow byway which connected the front row of the village with the back, and down this byway, drunken men frequently came staggering after too freely partaking of the wares of the publican. Sometimes a man would be so overcome when he reached the main road that he would throw himself down on the grass that bordered the wheel tracks and lie there for hours in tipsy stupor, while the rest of us who travelled that way passed by on the other side like the priest and Levite of old. These inert figures were most often stretched on the turf near the outskirts of the clachan, with the "U. P." (United Presbyterian) kirk looking gloomily down from just over the hedge. The local "polis" had headquarters a mile down the road, and a lone policeman was often in the village, but he never interfered with a drunken man as long as he was moderately peaceable. If a man fell by the wayside, the polis let him lie there. The U. P. Church was at the end of the front row of the village, and immediately behind it was the Free Kirk, at the end of the back row. Both were plain, small edifices of stone. The U. P. was entirely without ornament, but the Free had a tiny porch at the entrance, and up aloft on the peak was perched a little cupola with a bell in it, while at the rear of the edifice was a vestry. The diminutive size of this vestry made it seem as if it had been built for a joke. Here is Ian Maclaren's realistic description of it from "Beside the Bonnie Brier Bush": "The Free Kirk people were very proud of their vestry because it was reasonably supposed to be the smallest in Scotland. It was eight feet by eight, and consisted largely of two doors and a fireplace. Lockers on either side of the mantelpiece contained the church library, which abounded in the lives of the Scottish worthies, and was never lightly disturbed. Where there was neither grate nor door, a narrow board ran along the wall, on which it was a point of honor to seat the twelve deacons, who met once a month to raise the sustentation fund. Seating the court was a work of art, and could only be achieved by the repression of the smaller men, who looked out from the loopholes of retreat, the projection of bigger men, on to their neighbors' knees. Netherton was always the twelfth man to arrive, and nothing could be done till he was safely settled. Only some six inches were reserved at the end of the bench, and he was a full sitter, but he had discovered a trick of sitting sideways and screwing his leg against the opposite wall, that secured the court as well as himself in their places, on the principle of a compressed spring. When this operation was completed, Burnbrae used to say to the minister, who sat in the middle on a cane chair before the tiniest of tables — "'We're fine and comfortable noo, Moderator, and ye can begin business as sune as ye like."' Ian Maclaren, or, to use his real name, the Rev. John Watson, was the minister of the Free Kirk in early life and lived in the adjoining manse, a substantial and pleasant house that in its situation is uncommonly favored; for it turns its back to the village and looks down on a sweet little dell through which rambles a clear, pebbly brook. The view from the manse is extensive, and to the north the hills sweep up finely to dim ranges of the Grampians dreaming in the distance.  On the Moorland The Drumtochty folk esteemed Dr. Watson a very clever man, but they did not care much for his writings, aside from the interest stirred by their purely local flavor. His descriptions of character, and the humor and the pathos, were largely lost on them. When the "Brier Bush" stories first appeared the U. P. minister in his delight over them read one of the most laughter-provoking chapters at a meeting of his elders. But the elders were perfectly imperturbable, and sat unmoved to the end. The minister did not repeat the experiment. The inhabitants saw nothing of story interest about the region or about themselves; and if truth be told, any visitor who goes there expecting something extraordinary will be disappointed. Surrounding nature is by no means especially picturesque or beautiful, and life runs the usual course of labor, gossip, and small happenings. It is the author's skill that transforms all this in the books and makes ideal and heroic much that in the reality seems dull and commonplace to the uninspired observer. One book character of whom I often heard was Dr. Leitch, who, a good deal modified, is the lovable Dr. Maclure of the "Brier Bush." He had been dead now a score of years, and I saw his grave among the others that huddled about the gray walls of the Established Kirk in the little parish burying-ground. But the doctor was never any hero to the Drumtochty folk. Their view was quite disparaging. He was a picturesque figure, awkward and rudely clad, and his professional methods were as crude as his outward appearance. Still he was a fairly good doctor when you caught him sober. It was proverbial in Drumtochty that he was all right if his services were asked when, mounted on his white horse, he was riding east; but when he was returning west he was sure to have visited the public and was worse than no doctor at all. Often, on his way home, he was so exuberant with the "mountain dew" he had imbibed that he rode along like a mad man, swinging his hat on his stick and singing, "Scots wha ha'e wi' Wallace bled," at the top of his voice. Of all the people who figure in Dr. Watson's narratives perhaps the one who was copied most faithfully from life is the guard of the Kildrummie train. Kildrummie, six miles distant from Drumtochty, is the nearest railway town. A short branch line extends to it from the main route that connects Perth with Crieff, and a single train runs back and forth between the town and the junction. This is pulled by a superannuated little engine which is said to sometimes fail on the up grade so that the passengers have to get out and push. The guard, or conductor, as we would call him, is the Peter Bruce of the "Brier Bush" stories to perfection, and every reader of the tales who journeys to Drumtochty recognizes him at once and always calls him Peter, entirely independent of the fact that his real name is "Sandy" Walker. It was a pleasure to watch this gray little old man, he was so bustling and good-natured, and his eyes were so full of twinkle. He looked after the welfare of the passengers as attentively as if they were his children, and it seemed to come natural for him to get acquainted with all strangers and to find out their business the first time they rode on his train. He always spoke as if he did not relish the notoriety the books brought him, yet I fancy his protests were mainly bluff. Probably it will be a long time before he sues Dr. Watson for "defamation of character," as he hinted was his intention. He did his best to correct romance by a relation of the actual circumstances. "Oh, I ken Watson fine!" he said, "but thae books are two-thirds lees. The Drumtochty men were aye a drunken lot. It's a' very true aboot their stannin' aroon' on the Junction platform, but it wasna for the clatter that Watson tells aboot — it was because they was too drunk to know enough to get on the train. Mony's the time they had to be put on — pushed into their places like cattle, or lifted like bags o' grain." No doubt Peter's trials with the stubborn farmers of the uplands made him take an extreme view of their failings; but it was true that the Drumtochty folk were addicted to liquor beyond anything I am familiar with in rural America. Nearly all the farmers drank in moderation, and even a church elder could stagger after a visit to Perth without losing caste. Yet whatever their lacks, past or present, one would have to travel far to find people more kindly and whole-souled. They make hospitality a fine art, and if you asked a favor, even of some old farmer in garments that would shame a scarecrow, it was sure to be granted with a courtesy that won your affection on the spot. Another attraction which the Drumtochtians possessed in common with all the Scotch was their peculiar patois. The burr was always present, and they never failed to roll their r's, while a ch was sounded low in the throat in a way that made you wonder enviously how the children had ever caught the knack of pronouncing it. When reference was made to anything diminutive the ending ie or y was commonly added, and the word thus softened and caressed was very pleasant to the ear, and a decided improvement, I thought, over plain English. The only time I had any doubts about this extra syllable was when a woman spoke of her "Mary's little gravy," not meaning any portion of the family bill of fare, but the spot in the burial-place where lay a child she had lost.  A Schoolroom Corner in Drumtochty College Perth was the commercial centre of the district, and business or pleasure, or more likely a combination of the two, took most of the people of Drumtochty there very frequently. The Kildrummie train was not the only public conveyance thither. Twice a week a short omnibus, or "brake" as it was called, made the journey, starting from Drumtochty in the early morning and returning the same evening. The round trip was twenty-two miles. It was not as tiresome as one might fancy — at least that was my experience on the only occasion I took advantage of the vehicle. I recall the return journey with most interest. The brake stood by the curbing on Perth's chief street ready to start when I climbed in. A moment later the driver came out from a near public, mounted to his seat and off we went. But we had not gone far when a small boy in a tradesman's apron came shouting along the street after us with a great bundle in his arms. Other boys, nearer, took up the cry, and our driver became cognizant of the hubbub and halted until the lad came panting to the wagon side and passed up his bundle. Again we started, and again we were stopped almost immediately by a woman, who hailed us from the sidewalk. She climbed in, but pretty soon said she was in the wrong brake, and had the driver let her out. The horses had just begun to trot once more when we heard a halloo in the far distance behind, and saw two women and a man hastening in our pursuit, all three laden with a great variety of parcels. We waited for them and they squeezed in, stowed what parcels they could under the seats, and handed the surplus to the driver to be packed away in front. Some of the passengers were in danger of finding their sittings cramped, but when the driver questioned them they always said they were fixed "fine," and everybody tried to make everybody else as comfortable as possible. Thus we jogged on up and down the hills until we began to near our destination. Every now and then in this part of our journey one or more of the passengers would call to the driver, and he would pull in his horses and roll down from his seat to help them in alighting. This done, and the bundles handed out, he said, "Good nicht, and thank you kindly," and we were off once more. Often people on the watch would run out from wayside houses to get parcels brought by the driver or to meet friends, and sometimes a lone boy would be in waiting at the entrance to a lane that led away to a farmhouse. In the village itself there was quite a bustle of unloading, with half the inhabitants loitering in home doorways, or on the sidewalk, watching proceedings. During my stay in Drumtochty hardly a day passed in which I did not get out for a walk, and I gradually explored all the region within tramping distance. I became familiar with the windings of the Tochty, as the river in the hollow was called, and knew where it was swift and stony, and where it was quiet and deep. I followed up the side ravines through damp woods and open fields. I climbed ragged, rocky gorges where were constant waterfalls sliding into dark pools — ideal lurking-places for the wary trout. I acquired the names of all the burns and of several lesser rivulets that the natives called burnies. It did not take me long to learn the village with its front row and back row, and its three or four narrow lanes, nor the main road for a number of miles east and west; but the byways and field paths, the farms and the outlying pasture lands, were not as easily conquered.  Kathie scrubs the Front Walk I often went up in the evening to the edge of a moor, a half-mile back on the strath. There I would linger till after sundown. This upland was perfectly treeless and stretched away in a boggy level to some low hills far off in the west. Occasional sheep picking about gave almost the only hint that the land was of any human use. Once I saw five brown deer grazing in the distance, but usually, except for the sheep, I had no company save the peewits and whaups (curlews) and other "muirfowl" which screamed and flapped about in the twilight, making great ado over my presence. The whaups were strange, large birds with long, bent the edges of the woods and fields, and when they heard my footsteps, up they sat on their haunches, all alert to interrogate the nature and intents of the intruder, and then they went bobbing away in great terror to their holes in the banks along the hedges. They were such gentle, domestic little creatures, with their sensitive ears and stubby tails, and had such a soft, twinkling way of flying to cover when they took fright, that I always welcomed encounters with them, no matter how frequent. Gulls were common at this season in the Drumtochty neighborhood, for it was their nesting time, and they had come inland to breed. They made their homes by hundreds in the reeds at the borders of a shallow pond a few miles up the valley. I saw their white wings flipping about at all hours of the day, and noticed them frequently feeding with "craws" in the newly ploughed fields. I often heard the skylarks singing in their aerial flights, and there were great numbers of other song-birds, many of them tame almost to the point of sociability. Their companionableness was evidenced most clearly by the way they would hop along the roadway and the hedges in my vicinity, and by their approaching to within arm's-length when I sat down in a woodland coppice or among the alders that fringed a streamside. I perhaps ought to say before leaving this subject that my walks were not always an unmixed pleasure. There were times when the midges attacked me, and it was astonishing that such tiny creatures could be so irritating — "awfu' wild little things" my landlady called them. They were so persistent and so hard to catch, and their bites were so discomforting, that I concluded I would rather take my chances among our American mosquitoes. But the midges had one virtue the mosquitoes have not — they confined their operations to out-of-doors. There was the more reason for thankfulness in this because the houses usually furnished other creatures to battle with.  "A Wall of Crockery" Among other places to which I was attracted in my rambles was Trinity College, across the Tochty. It has a noble square of buildings, and looks as if it might have been transplanted from Cambridge or Oxford. To it come yearly several hundred sons of the gentry from all over the kingdom to prepare there for the universities. Their ages vary from eight to fifteen years, and to such youngsters the immediate surroundings of the college were, I thought, particularly attractive. The grounds themselves included wide sweeps of lawn that gave ample opportunities for games, and there was a shooting-range, and there were swimming holes conveniently near in the Tochty, while the neighboring hills and dales, with their patches of woodland, their moors and trout brooks, offered many varied pleasures. In what I saw of the college interior I was most impressed by an apartment set full of ancient battered desks that looked as if they had been suffering at the hands of youthful savages of the schoolroom from time immemorial. They were in truth so dark and grim as to be more suggestive of a penal institution than a modern school; yet both students and faculty are very proud of these desks. They take pains to show them to all visitors, and call attention to the fact that there are very few schools in Britain that can boast of anything older or more defaced by accumulated scratchings and carvings. The desks were heavy, rudely made affairs, standing back to back. On top rose a series of bookshelves which apparently separated the boy on one side from the lad who sat facing him on the other side very effectively. But closer observation showed that the boys always kept a friendly hole cut through the partition. In decided contrast with the desks were the modern electric lights with which the room was fitted. Pride in antiquity did not go to the length of studying by candle-light. The students in their dress were quite unlike the local inhabitants of the district. On week days they went about hatless in all sorts of weather, and wore a very light costume that left the knees bare. In winter, too, hatless heads and bare knees were still the fashion, and frost and falling snow made no difference. The boys discarded head-coverings to promote the growth of their hair, and the scantiness of their other apparel was imagined to assist them in acquiring an athletic toughness. But on Sundays there was a change. Then they wore chimney-pot hats and blue suits, with long trousers and Eton jackets, and they looked like grown men boiled down. My home while in Drumtochty was, as I have mentioned, at the shoemaker's. The house was one of several joining walls in the front row of the village. It had four rooms. Of these I had the parlor and bedroom, while the shoemaker, with his wife and two children, occupied the kitchen and scullery. In a corner of the kitchen was a bed, and by the fireplace was a great, wide chair that could be opened out and made into a sort of crib. This chair-crib was pushed up beside the bed every night, for the use of the little girl, Cathie. Jamie, the boy, slept next door, at his grandmother's. All the humbler village homes were like the shoemaker's, in having one or more beds in the kitchen. Often the bedsteads were simple modern frameworks of iron, but in many instances they were old-fashioned box-beds, more like cupboards or closets than beds. But the main feature of a kitchen was always a black fireplace, its lower half filled across by a "grate." This grate consisted of an oven on the right hand, and a tank for hot water on the left, between which was an open space for the fire with bars across the front. Most of the cooking was done on griddles and in pots that were either set on the coals or hung over the blaze from the crane. To start the fire, dry twigs of broom, cut on the near braes (hillsides), were first put on, then a few sticks of kindling-wood added, and on top of all, some of the great lumps of soft coal that are used nearly everywhere in Britain. The broom, when it was touched off, made a very brisk and pleasant crackling, and the fire itself, as long as it burned, lent to the most commonplace apartment a relieving touch of cheerfulness. I greatly enjoyed my parlor fire, and on days of driving rain and chilling winds, often sat long before it, watching the dancing and beckoning of the rosy sprites released from the prisoning coals. At the approach of mealtime my landlady would come in, put a white spread over the centre table, and set forth various dishes from the parlor cupboard. Then she brought from the kitchen the food she had prepared. I fared simply, yet always had what was good, and plenty of it. I liked to eat real Scotch foods, and I had bannocks and scones at every meal, and pancakes and kail-broth not unfrequently. Breakfast invariably began with a soup-plate full of the coarse oatmeal of the region, but I drew the line at eating it without sugar, though my landlady assured me that the only proper way to eat it was with milk only. Nor could I quite reconcile myself to the Scotch butter. It has an individuality of its own, and when I first tried it I had the notion I was eating some new sort of cheese. But the trouble was that the butter was unsalted. The Scotch prefer it so, and even at fashionable hotels fresh butter is set before you, unless you request something different. My meals at the shoemaker's were served very tidily, but this was not typical of the family meals in the other part of the house. I suppose the kitchen and little room behind it, known as the scullery, had to serve too many purposes to be very neat. They were crowded and disorderly, and it was a mystery how the housewife managed to get through all her work without coming to grief. The family had an exceedingly plain bill of fare, and they were very economical in the use of dishes. They rarely, if ever, ate together, but each one sat down when he or she found it convenient. The few eatables that made a meal were always close at hand, and it took only a moment to put them on the table. Cathie was the last to eat in the morning. She lay abed till after eight, and when she did get up she breakfasted in her nightgown. With her knees on a chair and her elbows on the bare boards of the kitchen table the towsled little girl would finish her plate of porridge and call out, "Maw, got my tea ready?" She had to have tea with every meal, but her mother took care it should be very weak. After breakfast followed dressing and making ready for school, and then a mate would come to the door and both little girls would walk away up the road, hand in hand, each with a dinner bag strapped over her shoulder. In the home doorway stood Cathie's mother and watched the bairns till an intervening hedge hid them from sight. The shoemaker ate with his hat on unless the occasion was one of those special times when company was present and the kitchen table had been made imposing with a white spread. But there was nothing peculiar about his keeping on his head-covering. Every Scot wears his "bonnet" in his own house. It is a sign that he is at home and not visiting. Some say the cap is the first thing he puts on when he gets out of bed in the morning and the last he takes off at night; and there are Scotch workmen in America who, having eaten supper bareheaded out of deference to the customs of the land of their adoption, will get their caps and wear them the rest of the evening, even if they stay indoors until they retire. The scullery at my boarding-place was a nondescript room with many shelves along the walls and numbers of tubs, kettles, and odds and ends about the floor. The back door was here, and just outside were pails to receive the refuse and dirty water of the household. These pails were carried up into the garden and emptied only when necessity compelled. The kitchen was hardly less generously supplied with shelves and cupboards than the scullery. Prominent among these was the dresser, or "wall of crockery," opposite the fireplace. The lines of plates and cups and other decorated ware on the dresser, and the row of mugs pendent along a near beam, were kept in shining order if none of the other household furnishings were. I think the wall of crockery, the stiff best room, and the little patch of flowers at the front door were the three chief points of pride in most cottage homes. The gardens between the two village rows were planted to tatties (potatoes), kail, cabbages, onions, peas, etc. In a sunny corner would be a bunch of enormous rhubarb with stems as thick as one's wrist and leaves a yard broad. Small fruits were represented by gooseberries, currants, strawberries, and "rasps." Often there was a cherry tree or two, and, more rarely, an apple tree. The most notable Drumtochty apple tree stood in the midst of the manse garden next the Free Kirk. This was a stunted, shrublike tree pruned down to about the height of a man. A record of its apples was carefully kept, and the minister was willing to take his oath it had produced as many as 143 in a single season.  Village Bairns The shoemaker and his wife often worked together of an evening in their home garden. Cathie worked with them too, though her energies were mostly given to setting out in a neglected corner that she called her own various weeds and grasses that she had pulled up. Cathie was aged five. She was plump, red-cheeked, and good-natured, but with strangers was so shy she hardly let out a word, and she would drop her head the moment she caught any one looking at her. Among her companions or alone she was lively enough, and her tongue was capable of keeping on the trot all day long. Often she entertained herself by singing, and on a rainy day she would very likely play circus in the kitchen by the hour. She had seen a show at some time, and had taken a fancy to the right-rope lady. So she would imagine herself in a spangled dress, lay a narrow board across two chairs and dance on that with an old cane for a balancing stick. She at first begged for a rope to tie between the bedstead and the table, but her mother thought it best she should begin more humbly. Occasionally, when another little girl came in on a dull day, the two would play the dambrod (checkers); but Cathie was not clever at that, and after she had been beaten two or three times her opponent would say to her, "I'll hae to tak' aff yer heid an' pit on a neep" (turnip), and then Cathie would refuse to play any more. Drumtochty and the country for miles round about was owned by the Earl of Mansfield. He was one of the richest of Scotch landed proprietors, and his residence was at Scone Palace, near Perth. There was little liking for him among his tenantry, for he showed slight interest in their prosperity, and was quite content to see the farms degenerate into grazing moorland; and such was his partisanship for the Established Kirk, of which he was a supporting pillar, that he discriminated against dissenting tenants — at least this was common report. But the clachan on the strath, although it belonged to the Earl, was not wholly in his power. It was built on land leased for a term of ninety-nine years, and about a quarter of this time was still unexpired. Houses and churches, both, were built by the people, but all would be the Earl of Mansfield's unconditionally in twenty-six years. Nevertheless, there was no fear of any special severity; for, whatever might be a landlord's personal pleasure, he would not dare go against the public sentiment of the nation, and the dissenters will continue to have their kirks and their ministers. The district had become the property of the Earl comparatively recently. For many generations previous it had been the domain of the Lairds of Logie, whose ancient home still stands about a mile east of the village, not far from the Auld Kirk. In the early part of the last century Logie House had been a fine mansion with beautiful grounds surrounding. Now the place has gone to decay, and the great mansion is unoccupied save by an old woman and her daughter, who have two rooms in the second story. It is in a retired spot well back from the main road, in its old-time park, and the quiet is such that the wild rabbits feed fearlessly in the grassy roadway right before the grand front door. If you go inside you are shown through many lofty rooms, with wall and ceilings bare and stained, their frescoing and marble fireplaces cracked, and their high windows staring curtainless out on the trees and shrubbery of the park. Back of Logie House is a still more ancient residence of the Lairds of the district, larger and much more ruinous. The roof is gone, the upper floors have fallen, the walls are crumbling; and grasses, rank weeds, bushes, and even good-sized trees grow in the old halls. I explored a secret hiding-place in a tower, where a winding stair crept up behind what had been a china closet, to a black pocket of a chamber above, and I went down into the gloomy passages and vaulted rooms of the cellar. Some of these underground rooms had grated windows, and were so dismally dark and damp that they were exact counterparts of the traditional dungeon; and the whole ruin was enchanting in its suggestion of mysteries, ghosts, and the rough fighting days of centuries ago. Logie House was perched high on a hill slope that commanded a long view down the winding valley of the Tochty. In the wooded depths of the hollow could be caught glints of the stream, and on a quiet day you heard its far-off murmur. A footpath threaded through the woodland down the valley, most of the way keeping high up on the edge of a precipitous bank, with the river a hundred feet or so below. The trees along this path were very fine. They grew clean and large and tall — firs, larches, pines, lime trees, and graceful beeches. The evergreen woods were perhaps the most attractive of all, not so much in themselves, however, as in the fact that no matter how thick the trees were the ground beneath was very sure to be delicately carpeted with thin green grasses. This light undergrowth was very pleasant to the eye, without being heavy enough to appreciably obstruct one's footsteps. Another thing noticeable in the woods was the absence of dead leaves on the earth. The climate is so damp they soon mould and become a part of the soil. The effect of the dampness was further shown by the heavy moss which grew on tree trunks, shadowed fences, and decayed branches, and frequently was so pronounced as to be shaggy and pendent. In a forest dell, two miles down the path in the valley of the Tochty, is a rough cairn of stones which marks the spot where dwelt long ago Bessie Bell and Mary Gray of the old ballad. It was a time of plague, and these two young women, daughters of the nobility, fled from their homes and built a woodland hut here. "O

Bessie Bell and Mary Gray,

They war twa bonny lasses! They bigget a bower on yon burn-brae, And theekit it o'er wi' rashes." In its seclusion they intended to live till the dangers of contagion were past. But their lovers presently sought them out, and unfortunately at the same time brought the plague with 'them. Both maids took the disease and died. After their death the attempt was made to take their bodies to the town. But when the bearers came to the ford in the river some distance below, the authorities, fearful that the plague would be spread, refused to allow them to cross. So Bessie Bell and Mary Gray were buried by the waterside near the ford, and now a weather-worn shaft of stone enclosed by a rusty, decrepit square of iron fence marks their grave. Close by is a second cairn of stone, which no doubt was piled up to mark the maidens' resting place long before the monument within the iron fence was erected. The great trees tower up overhead and make the glade below very shadowy and quiet save for the unceasing ripple of the near stream; and the day I was there the stillness and wildness of the spot were accentuated by the appearance of a little mouse that crept in and out of the crannies of the stone heap.  Logie Ruin As I was loitering along the path on my way back to Logie House I was overtaken by an old shepherd with a crook in his hands and a collie at his heels. It's vera warum thae day," he remarked by way of greeting. The Drumtochty folk never said "Good morning," or, "Good afternoon," but instead made some comment on the weather, declaring it was warum, cauld, stormy, or whatever it happened to be at the moment. Their statements did not always seem very literal. For instance, "stormy" simply meant windy, while "rain" was a term only used to express the superlative. The drops might be falling thick and fast, and yet a man responding to a friend who had mentioned that it was "Shoorie like," would be apt to say, "Ay, Tammas, but there'll no be ony rain." A rain in Scotland means an all-day downpour. This kindly view of the weather was further illustrated by their calling any day "fair," no matter how gloomily clouded the sky, so long as there was no actual precipitation. According to the shoemaker's wife, if on a threatening day the water drops had descended "to the roof o' the hoose and werena come doon to the ground yet, we wad say it was fair — fair, but a bit dull like." The old shepherd showed an inclination to be sociable, and I kept on in his company. He said his age was eighty, but that he still kept at his work and walked many miles daily. Nearly all his long life had been spent in tramping the Drumtochty moorlands within a narrow radius of his home. But there had been one journey to the outside world that took him as far as the royal castle at Balmoral. He recalled this trip with peculiar pleasure and animation. He advised me that I must not fail to see the castle, too, and he would recommend that I should view it from a certain hill. Seen thence he declared it did look beautiful and "stood up juist as white and fine as a new-starched shirt." On his visit to Balmoral the shepherd had seen a man who was making a tour of Scotland exhibiting his prowess as an archer, "and he was an Ameerican, like yoursel'," the shepherd explained — "a cannibal, aye, one o' them Injun fellers." Then he told of one of his relatives who had lived in America and now had returned to his native Scotland, and who said that nothing could induce him to marry an American woman. Rather than that he would "coom awa' hame and marry a tinker (gypsy), because thae Ameerican weemen's na strang. Their lungs gang awa' frae them." It was the shepherd's impression that we Americans still lived in the midst of the primeval forests, through which roamed all sorts of savage and ravenous beasts. He made particular inquiry about our American snakes, and said he had been told about a "sarpint" twelve feet long, and he understood that such "sarpints" crawled into our houses and under our beds!  Conducting her Coo to Pasture |