| STRUCTURE

OF THE PLANTS.

If

we closely examine the varieties of any one species of the

Strawberry, we find that they resemble each other in their general

habits or manner of growth. No one at all familiar with these plants

would ever mistake an Alpine Strawberry for one of any other of the

well-known species, and even the Hautbois Strawberry, which, in some

respects, resembles the Alpines, is sufficiently distinct to be

easily recognized. There are varieties of the Wood or Alpine species

that produce no runners, growing in clumps or stools; still the

foliage plainly shows their origin, and, as we have no hybrids

between the Alpines and other species, there is no difficulty in

recognizing them wherever found. But with the North and South

American species or Virginian and Chilian Strawberries the line

of demarcation is not so easily determined as formerly, because

they hybridize so readily that their specific characteristics have

become almost obliterated in the cultivated varieties.

The

Chili Strawberry in its wild state produces larger and milder

flavored fruit than our common American or Virginia Strawberry, and

probably for this reason it has been a favorite with the cultivators

of the Strawberry in Europe, and nearly all of the noted varieties

raised abroad are of this species. This is why so few of the European

varieties, as they are termed, succeed in this country, having

descended from a semi-tropical species. But in recent years the

European and native sorts have been crossed and so thoroughly

intermingled that it is only occasionally that we can detect the

peculiar and distinct characteristics of either species in the

common cultivated varieties.

Fig.

6 —VIRGINIA STRAWBERRY

In

the old Triomphe de Gand Strawberry we have a pure descendant of the

Chilian species, and in the Wilson's Albany and Charles Downing,

pure native blood. The Wilson may be considered as a large

representative of the Wild Strawberry of the Eastern States, and the

Downing of the Western or of F. Virginiana var.

Illinoensis.

Fig.

7 — CHILI STRAWBERRY

The

varieties of our native species usually have long thread-like or wiry

roots, which penetrate the soil deeply and spread widely in search of

nutriment and moisture, while the roots of the pure Chilian varieties

appear to be more fleshy, shorter and not so hard and firm.

Another

peculiarity in the form and structure may be observed by an

examination of the old and mature plants. In our native varieties,

like the Downing and Boston Pine, they appear to remain low down in

the soil — not inclined to push above the surface — dividing

naturally, as shown in Fig. 6, while the Chilian varieties

assume the form shown in Fig. 7, which is an exact

representation — half natural size — of a three year old

plant of the Triomphe de Gand. It will be observed, by examining the

illustration, that all of the crowns are united to the main or

central one, with little. inclination to separate from it. These

elevated crowns contain the embryo fruit-buds, and the more they

extend above the surface of the soil the more likely they are to be

injured by the frosts of winter.

Varieties

of this form of root or crown soon extend, so far above the surface

that their new roots cannot, or at least do not, take a firm hold of

the soil in sufficient numbers to supply the plant with nutriment.

There

are many excellent varieties in cultivation that are inclined to

assume this form of growth, and they require somewhat different

treatment from those with shorter and. low-spreading crowns, as shown

in Fig. 6. When the latter are cultivated in hills or single rows,

the soil may be drawn up against the plants as their crowns protrude

above the surface, covering the new lateral roots, thereby increasing

the vigor and prolonging the life of the plants.

PROPAGATION.

The

three most common modes of propagation of the Strawberry are, viz.,

by seeds, runners and divisions of the crowns or stools. The first

mode, or by seeds, is practiced mostly for the purpose of producing

new varieties, but the wild plants of all the species reproduce

themselves from seed with very slight variations, and it is only from

the already improved varieties that we can expect to raise new ones

of any considerable value. If, however, we fertilize the pistils of a

wild plant with pollen from an improved one, we stand a fair

chance of obtaining seedlings showing an advance upon the wild

or parent plant. However, unless there is some special object in view

— such as extreme hardiness, or the adaptation of a variety to a

certain soil or situation — it is better to save seed from the

improved sorts than to go back or resort to the primitive or wild

species for a supply.

To

obtain seed it is only necessary to select the ripe berries, and

either crash the pulp and spread it out and dry it with the seeds,

thus preserving both, or the fruit may be crushed and the seeds

washed out. The sound good seeds will fall to the bottom, and the

pulp and false ones remain on the surface, from which both may be

readily removed. I have found seed preserved in the dried pulp of the

Strawberry remain sound and good for several years, and, if it is to

be kept for any considerable time, I should much prefer to have it

preserved in the pulp than to have it removed or washed out, but the

berries should be thoroughly dried and then put away in paper bags as

usually practised with clean seeds. I have received dried

Strawberries from Europe that were several years old, the seeds of

which, when soaked and washed out, sprouted almost as readily as

fresh ones.

My

usual practice in raising seedling Strawberries has been to gather

the largest and best berries, then mix them with dry sand, crushing

the pulp between the hands and so thoroughly manipulating the mass

that no two seeds will remain together. Then set away the box

containing the sand and seed in some cool place until the following

spring. Then sow the sand and seed together either in some

half-shady situation in the garden, or in pots, boxes or frames. The

soil in which the seed is sown should be of a light texture, to

prevent baking of the surface after watering. The seed should be

scattered on the surface, and fine soil sifted over them to a depth

of not more than one-quarter of an inch, or less than one-eighth.

Apply water freely with a watering pot or garden syringe, using

a fine rose in order that the water shall fall on the surface in the

farm of spray instead of a stream, as the latter is likely to wash

out the seed. By keeping the soil moist the plants will usually

appear in two to four weeks after sowing, and, if sown under glass or

in warm weather, in less time.

If

the plants do not come up so thickly as to be crowded, they may

remain in the seedbed during the entire season, but usually it is

better to transplant them into rows in the open ground where they can

have more room for development. All runners should be removed the

first season in order to secure as vigorous growth of the original

plant as possible. The following season the plants will bear fruit,

when the best and most promising may be preserved and the others

destroyed. It must not, however, be expected that a one-year-old

seedling is a fully developed plant, and for this reason it is well

to preserve all which give promise of excellence.

If

the seed is sown as soon as it is removed from the freshly-gathered

fruit in summer, it will sprout in two or three weeks, and produce

plants with several well developed leaves before the end of the

season, and, if given protection the first winter, they will make a

vigorous growth the next, and become somewhat larger plants than

those raised from seed sown in the spring of the same year. It is

best to give the seedlings some protection in cold climates in

order to secure their full development.

When

the plants come into bloom they should be carefully examined, and

those with pistillate flowers — as these will usually be the least

numerous — marked so that they will be known when the fruit is

ripe. When a variety has been raised that promises to be valuable,

the plant should be carefully lifted during rainy weather and set out

by itself for propagation.

The

plants may be removed from the seedling bed or rows soon after the

fruit is mature, or its character fully determined if carefully

lifted, and then given plenty of water and shaded a few days after

re-planting. It is not at all difficult to raise new varieties, but

to obtain one. worthy of propagation and dissemination is quite

another matter, and the chances are not more than one in a thousand

of obtaining a new variety from seed equal to the best of the old

ones now in cultivation. It is well enough, however, for every person

who has the time to spare and inclination to experiment, to try,

because there is not only a chance of producing varieties better

than any now in cultivation, but in addition the pleasure of watching

one's own seedlings grow and bear fruit.

Propagation

by Runners. — This is the natural method of propagation of all

the species and varieties except the Bush Alpines. The first runner

produced on a plant in summer is usually the strongest and best for

early removal, but those that are produced later in the season on the

same runner are equally as good when of the same age and size.

Certain theorists have, however, claimed that the first plant formed

on a runner near the parent plant was naturally stronger and better

in every way than those following or produced later, but long

experience has not proved this to be true. If the second, third

or fourth plant should happen to thrust its roots into richer soil

than the first one, they will become the larger and stronger plants

before the end of the season. To insure the rooting of the young

plants, the surface of the soil should be kept loose and open, and if

a top dressing of fine old manure can be applied just before or at

the time the runners are pushing out most rapidly, it will greatly

facilitate the production of roots.

Pot

Plants. — In the last few years what are called "pot-grown

plants" have become very popular among amateur cultivators, who

may desire to purchase a few plants and have them in the best

possible condition to insure rapid growth and early planting. To

accommodate this class of buyers our Strawberry growers have

made these pot-grown or layered plants a distinct feature of their

business. In propagating plants by this mode small two or three-inch

flower pots are filled with rich soil and then plunged in the ground,

around the old stools and in such positions as will admit of placing

a young plant while attached to the runner in each, or on the surface

of the soil in the pot so that the new roots will penetrate it. When

the new plants have produced a sufficient number of roots in these

pots to form a somewhat compact mass or ball of the earth

within, they are carefully separated, the pots lifted, and either

sent to the purchasers in the pots or knocked out, and each plant

rolled up separately in a piece of paper or some similar material.

Plants

that have become well established in the pots in time for planting

out early in the fall will often yield a moderate crop of fruit the

following season, which the amateur cultivator may value far more

highly than the professional who raises fruit for market. Pot-grown

plants cost more than those raised in the ordinary way, and they are

worth more, especially to persons who are anxious to test a new

variety or see Strawberries ripening in their own garden.

PROPAGATION

BY DIVISION.

This

mode is seldom practiced except with the Bush Alpines, which do not

produce runners. To propagate these varieties the old stools should

be lifted early in Spring and divided, leaving only one or two crowns

to a plant. If the old or central stems are very long, the lower or

older part may be cut away, leaving only the upper and younger roots

attached. In setting out again, the crown of the plant should be just

level with the surface of the soil in order that new lateral

roots may spring out above the old ones on the central stalk or stem.

SOIL

AND ITS PREPARATION.

In

its wild state the Strawberry is found growing in a great variety of

soils, from the rich alluvial deposits along rivers, up to the sand

hills and even bleak rocky ridges of Alpine regions. But as the

largest species and varieties are found growing in the richest soils,

so in cultivation we will ever find that large fruit, and this

in abundance, can only be secured by supplying a corresponding amount

of nutriment. New soils, free from weeds and noxious insects, are

certainly preferable to old, worn and badly infested; but as the

Strawberry grower can seldom have his choice in such matters, he must

use such as he has and overcome natural obstacles with artificial

remedies. A rather light soil or what would be called loamy soil, is

preferable to heavy clay, or the opposite extreme as seen in

sand and gravel. But natural defects can usually be remedied, for the

stiff cold clay can be improved by underdraining and subsoiling, also

by adding vegetable matter in large quantities. The main point to be

observed is to secure a good depth of soil with good drainage and

plenty of nutriment for the plants. Next in importance after

supplying what may be termed the substantial elements in the form of

nutriment comes moisture, for the Strawberry plant will use an

immense amount if it is obtainable, but stagnant water at the roots

or a constantly water-soaked soil are conditions to be avoided. A

soil that will allow the water falling in the form of rain to pass

down through it in a few hours, and still hold enough in suspension

to keep it moist for weeks, is a proper one for the Strawberry,

whatever may have been its original nature or condition.

Land

that will produce a good crop of corn or potatoes may be

considered in a fair condition for Strawberries, provided that

it is not so situated as to be in danger of flooding during the time

of the usual overflow of streams in winter and spring. But the

Strawberry requires a deeper soil than corn, and this may be

readily secured by deep plowing, or what is better, turning over the

surface soil shallow, and following with a subsoil plow, and in this

way avoid bringing the poorer subsoil to the surface. The land, if

naturally hard and compact, should be cross-plowed in the same way,

and, if manure is to be applied at all, let it be spread over the

surface before the first plowing, in order that it may become

well mixed and intermingled with the soil before the plants are set

out, that is, if ordinary kinds of composts or barnyard manure

are used. When commercial manures are employed they are usually

applied in the form of top, dressings at the time of setting out the

plants, or at various times afterwards as the plants may show

the need of more stimulants and nutriment.

Manures.

— The Strawberry is not so capricious as to refuse nutriment

in

almost any form when presented to its roots, but the quantity and

quality may be varied according to circumstances. On the rich

prairies of the Western States, or on newly-cleared land in the East,

no manure may be necessary in order to secure a heavy crop of fruit,

but the plants require nutriment in abundance, and, if it is not

natural in the soil, we must place it there in some form. As for the

kind of fertilizer to use, I have never, as yet, found anything to

excel thoroughly decomposed barn-yard manure. On light, warm, sandy

soils I prefer cow manure to that of the horse, as it is of a cooler

nature, but if manure from barn yard or stables is left in the yard

until it has become well rotted, or is composted with muck, leaves

and similar materials, it may be used on sandy soils, and in liberal

amounts without danger of over stimulating the plants. Bone dust,

superphosphate of lime, sulphate of ammonia, muriate of potash,

and wood ashes, may all be used where the land is poor or extra

stimulants are needed to force the growth and increase the size of

the fruit.

HOW

AND WHEN TO PLANT.

While

it is perfectly practicable to transplant the Strawberry at any and

all seasons of the year — except when the ground is hard frozen and

covered with snow — still there appear to be certain months during

which this operation may be performed with less labor and more

uniform success than during any other of the twelve. In warm

climates, as in our Southern States, the best time for setting out

the plants is late in the autumn or at almost any time during the

winter, but the earlier the better, in order to secure the benefits

of the cool moist weather during which the plants become well

established and in condition for growth at the approach of warm

weather in spring. But in cold climates late fall planting will, in

most instances, result in a total loss, as the frosts of winter will

lift the plants from the soil and destroy them. The two seasons most

favorable for planting the Strawberry in cold climates are early

fall, or from the middle of August to the first week in September and

early in the Spring. Fall planting, however, of the Strawberry is not

generally practiced in the Northern States except by amateurs and

with pot-grown plants. But in this matter of transplanting much

depends upon the season; if there is an abundance of rain during the

summer, strong, well-rooted plants may be obtained in August or by

the first of September, and if these are set out, and the weather

continues favorable, they will become well established by the time

cold weather sets in, and the following season make a much better

growth than if the planting was delayed until spring. But favorable

seasons are so uncertain that autumn planting is not a general

practice among those who make Strawberry culture a specialty.

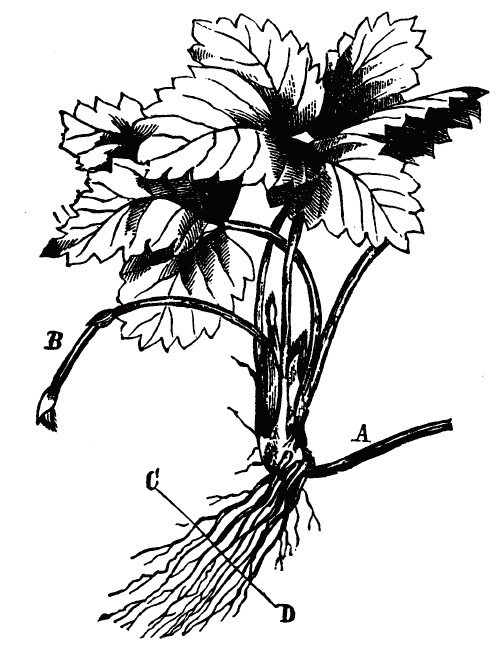

Fig.

8 —YOUNG STRAWBERRY PLANT.

When

transplanting in the spring, the half-dead leaves should be removed

and the roots shortened one-third or one-half their length. In Fig. 8

is shown a terminal plant on a runner as taken from the ground. A,

the runner connecting it with the parent plant. B, the tip of the

runner which would have extended and produced another plant had it

not been checked by frost.

C

— D, the cross line showing the point at which the roots should be

cut. This pruning or shortening of the roots causes the production of

a new set of fibres from. the severed ends. It also causes other

roots to push out from near the crown, and if a plant thus pruned be

taken up in a few weeks after planting, its roots will appear

somewhat as shown in Fig. 9. This pruning of the roots is not so

generally practiced as it deserves to be, especially with plants that

have been out of the ground for several days, or until the roots are

withered or have commenced to decay at the ends. No matter how

carefully the plants are taken up, some of the fibres will be

broken off, and it is much better to sever all the roots with a clean

cut than to plant them with ragged and broken ends. Roots pruned in

this way are more readily spread out when placed in the ground again

than when left intact or of full length.

Fig.

9 — PLANT WITH ROOTS PRUNED.

Selection

of Plants. — Young runners of one season's growth are

best, and old plants should not be used for transplanting, if it can

be avoided. But, if a variety is scarce and valuable, the old stools

may be taken up and pulled apart, and the lower end of the central

stalk cut away as recommended for the Bush Alpines, and then set out

again, planting deep enough to ensure the emission of new roots above

the old ones.

DIFFERENT

MODES OF CULTIVATION.

The

cultivators of the Strawberry are not all of one opinion in regard to

the best mode of cultivation either in the field or garden;

consequently, we hear much about raising Strawberries in hills, rows,

matted beds, annual renewal systems, etc., all of which may give good

results, with productive varieties and on rich soils.

But

different varieties often require a different mode of culture in

order to obtain the largest yield and the largest berries. The large,

coarse-grown varieties of the Chili species, or the hybrid between

these and the Virginia Strawberry, succeed best when grown in

hills or single rows, and they are usually quite unproductive if

the plants are permitted to run together and become in the least

crowded. The Triomphe de Gand, Jucunda, Champion, Agriculturist and

Lennig's White are well-known varieties of this type; while others,

such as Charles Downing, President Wilder, Green Prolific and

Manchester, will yield well either in narrow rows or wide beds, and

where the plants become matted.

In

the "hill system" the plants are usually set out in rows

about three feet apart, and the plants eighteen inches to two feet

apart in the row. The ground is kept thoroughly cultivated among the

plants daring the entire season, and all runners removed as soon

as they appear, or at least once a week. This treatment will

insure very large and strong plants, with numerous crowns or

buds, from which fruit-stalks will push up the following spring.

In cold climates and where the plants are likely to be exposed to

alternate freezing and thawing, or to cold winds during the winter,

they should be protected by a light covering of hay, coarse

manure, or some similar material — just enough to protect the

crowns from injury but not enough to prevent freezing. In the spring

the materials used for protection may be removed, and the plants

given a good hoeing or a cultivator run between the rows to

soften up the soil, which may have become hard and compact during the

winter; but this cultivation in the spring will depend somewhat upon

the character of the soil, for, if it is light and of a sandy nature,

it will not be necessary, but it will certainly do no harm and may

prove of great benefit to the plants. After the beds are cleared up

and before the plants come into bloom, the entire surface of the

ground should be covered with long straw or some similar material as

a mulch to keep the soil moist and the fruit clean when it ripens. It

is almost a waste of time to undertake to raise the large varieties

in hills without mulching the plants, for the largest berries are

almost certain to become splashed with soil during heavy rains.

When

grown in single rows the plants may be set about twelve inches apart

in the rows, and for garden culture the rows should be about three

feet apart, but for field culture I prefer to allow a little more

space between the rows, or four feet, but the distance may be

varied according to the habit of the plants — some of the

rank-growing varieties requiring more room than those of a medium

growth, but it is much better to allow the plants plenty of room than

to have them crowded.

During

the first season the plants must be given good cultivation, and the

more the soil is stirred among them the better, provided the roots

are not disturbed by the implements employed in this work. In the

field a one-horse cultivator is the best implement to use for keeping

the soil loose and free from weeds between the rows, and, while the

hoe may be used early in the season to stir the surface about the

plants, it will have to be abandoned later on when the runners push

out, for these are to be allowed to take root in the row, and form a

bed about one foot wide, and all that extend out beyond this may be

cut off or torn up with the cultivator. Some cultivators allow the

runners to take root over a space of eighteen to twenty-four inches

wide, leaving just room enough between the narrow beds to give a path

in which to stand in gathering the fruit the following season. It is

doubtful, however, if any more fruit will be obtained from a larger

number of small plants than from less but of a stronger and more

vigorous growth, as they are more likely to be, if restricted to a

narrow row.

If

protection in winter is necessary — and usually it is in our

Northern States — it should be given as soon as the ground begins

to freeze in the fall or early winter. If applied before the weather

has become cool and the nights frosty, there is danger of the plants

sweating and bleaching. Still, it is not well to delay covering up

until snow falls and prevents it.

Coarse,

strong manure from the stable or barnyard, scattered along over the

crowns of the plants, makes an excellent winter protection, but as

such material contains many weed seeds, it should be employed only on

beds that are to be plowed up after fruiting the ensuing season.

In fact, it will seldom pay the cultivator to clean out an old weedy

plantation, for it costs less to set out a new one.

Bed

or Matted System. — In this mode two or three rows are planted

in beds four feet wide, and the . plants allowed to cover the entire

surface until they form a close mat or bed; hence the name. One or

two crops are taken and then the plants are plowed up as usual when

cultivated in rows. But, by thinning out occasionally, the beds

may be kept in a moderately productive condition for several

years, especially with some of the more slender growing of our native

varieties. Some cultivators, who raise Strawberries for market, adopt

what may be called an annual system, setting out plants in spring

either in single rows or narrow beds, giving them extra care during

the first season, then, after the fruit is gathered the next summer,

the beds are plowed up. This mode necessitates the making of a new

plantation annually. On very rich soils and with the larger

varieties — which generally command the highest price in market —

this system is no doubt an excellent and profitable one. But

amateurs and others, who have only a limited space to devote to this

fruit, will prefer either the hill or row system, because, by

devoting a little more labor to cultivation and removing the runners,

the beds may be kept in good condition for fruiting a half dozen

years. By an occasional top-dressing of old and well rotted manure,

and forking in the materials used for protecting the plants and

a mulch, the soil will be kept in fine condition for insuring a

vigorous growth of plants. Old beds, however, are usually more likely

to be infested by noxious insects than new ones, in addition to

weeds, such as white clover, which are difficult to eradicate without

disturbing the roots of the plants.

Planting.

— The surface of the bed or field to be planted should be made

smooth, level and free from lumps and stones. If it is uneven and

there are many little hillocks and depressions, as are naturally left

after plowing, the plants will follow these undulating lines, and

some will be buried too deep and others have their roots exposed

after the first heavy shower.

Always

choose a cloudy day for planting, and it is far better to heel the

plants in for a few days and give them a little water and shade than

to set them out in dry weather. Draw a line where you are to set a

row of plants, keeping it a few inches above the ground, so that you

may plant under it instead of along one side. Use a transplanting

trowel for making holes for the reception of the roots, and

these should be spread out evenly in all directions, or spread apart,

so that they will lie against one side of the hole made with the

trowel Cover the plants as deep as possible without covering the

crowns, and then press the soil down firmly around the roots. Some

cultivators use a small wooden dibber for planting, merely making a

round hole in the soil into which the roots are thrust all in a

clump. Plants may live under such treatment, but careful planting

with a trowel is far the best mode. If the weather should prove dry

after planting, watering will, of course, be beneficial; but is only

practicable on a small scale, as in gardens, or where it may be

necessary to save some new and choice variety.

Where

pistillate varieties are raised for the main crop then every fourth

or fifth row should be planted with some hermaphrodite or perfect

flowering variety, which blooms at or about the same time as the

pistillate.

If

the plants are cultivated in wide beds, then about every third one

should be planted with some perfect flowering sort to supply pollen

to the pistillate plants. But, as I have said elsewhere, there is no

need of, or good reason for, cultivating these imperfect flowering

varieties at all, and, unless one should appear better than any as

yet known, they might all be discarded without loss to either

cultivators or consumers of this fruit.

To

Raise Extra Large Fruit. — First of all secure plants of

varieties known to grow to a large size, then plant in rich soil,

remove the runners as soon as they appear, keep the weeds down,

stir the surface of the soil frequently, apply water as often as

necessary, which will be at least twice a week in dry weather, also

give liquid manure occasionally; in fact, force the plants to make a

strong and vigorous growth. In the fall, or at the approach of

cold weather, cover the plants with hay, straw, or some similar

material, and in the spring remove it and spade or fork up the ground

between the rows, after which spread over the ground sufficient mulch

to keep the soil moist even during the time of drought. Under such

treatment extra large berries may usually be produced. The cost

of raising fruit by such modes of cultivation is, of course,

seldom taken into consideration, and it really ought not to be any

more than any other amusement devised for our own pleasure or that of

our friends.

Of

course, it is not to be supposed that large and fine fruit cannot be

raised without extra and expensive modes of cultivation, but I have

yet to learn of an instance where "astonishing" large

Strawberries have been produced without a corresponding outlay

in manure, labor and care.

POT

CULTURE AND FORCING.

It

often occurs that Strawberries ripening out of season are far

more valuable than those maturing in the usual or natural season.

Ripe Strawberries in mid-winter or even a month or two in

advance of the crop ripening out of doors, always command an

extra price in our markets; and, if a person does not care to raise

fruit to sell, he may take pride in having them on his own table out

of the regular season.

It

is not at all difficult to raise Strawberry plants in pots and force

them into fruiting at almost any season as desired, provided a person

has a greenhouse, pit or hot-house in which the plants may be stored

and forced with artificial heat during cold weather.

The

plants to be forced may be of either one or two seasons' growth. If

strong plants are desired and such as will produce a number of

fruit-stalks, small young plants should be potted in the spring,

using four or five inch pots for this purpose. The pots containing

the plants should be plunged in the open ground, and where water can

be given as required, and all runners removed as soon as they appear,

also flower and fruit stalks. In June or July shift the plants into

eight-inch pots, using very rich and compact soil. A few pieces of

broken pots or old sods should be placed in the bottom of the pots

for drainage, but the ball of earth about the roots must not be

broken when transferring from the smaller to the larger pots. Give

water to settle the soil in the pots, then plunge the pots in a frame

where they will continue to grow without check until the approach of

cold weather.

Plants

wanted for an early crop may be brought into the house in November,

as it will take from ten to twelve weeks from the time they are

placed in the house before ripe fruit can be obtained. The pots may

be plunged in tan or some similar material in the forcing house or

merely placed on the benches or shelves, but more care is required in

giving water, if the pots are exposed, than when plunged in tan or

soil.

If

a succession of crops is desired, then only a portion of the

plants should be brought in at one time.

The

temperature of the house should be only moderate at first, but

increased gradually as the plants commence to grow and the fruit

stems appear, when it should range from 65 to 75 degrees during the

day and about ten degrees lower at night.

The

plants will be benefited if syringed or watered overhead once or

twice a week until they come into bloom; then omit it until the fruit

is set, after which it may be continued as before. While the plants

are in bloom, admit as much air as possible without lowering the

temperature to a dangerous. degree, and, as there will be neither

wind or insects to scatter the pollen, it is usually necessary to

scatter it artificially. This can be done very rapidly with an

ordinary camel's hair brush or pencil, lightly touching the stamens

and pistils as each flower becomes fully expanded. This is not

necessary with every variety, but a larger and more uniform crop will

usually be secured if practised on those fruiting most freely in the

house.

The

plants that are kept for forcing later in the season should be

stored in a cold frame or pit, where they will remain in a dormant

state until ready for use.

Plants

of one season's growth or those struck in pots during the summer will

answer well for forcing in winter. The plants will not be as

large as older ones, or produce as many berries, but, as they are

smaller, a greater number can be forced in a given space. The first

or earliest runners should be selected for this purpose, and a

three or four-inch pot plunged in the ground underneath, or if roots

have formed on the young plant when the pots are set in place, they

may be thrust into the pot and good soil filled in about them. These

pot-grown plants should be lifted early, or about the first of

October, and shifted in to five or six-inch pots, filled with very

rich compost and plenty of drainage — thenceforward treated as

advised for older stock.

Such

pot-grown plants may be fruited in the windows of an ordinary

dwelling, provided the temperature does not fall below 40 or 45

degrees at night. The best varieties of the Strawberry for the

purpose, however, are the Monthly Alpines, as they will thrive in a

lower temperature than those of other species, and, with

ordinary care, will continue to bloom and bear fruit all the year

round. Fruit is not produced in any great abundance at any one

season, but, the crop being a continuous one, it amounts to a pretty

fair quantity during the year. As an ornamental window or greenhouse

plant there are very few bearing edible fruit worthy of more care or

attention than the Monthly Alpine Strawberry.

VARIETIES

FOR FORCING.

Nearly

all of the perfect flowering varieties succeed when forced under

glass, but the largest and most prolific are to be preferred,

because size and quantity are properties sought more than high

flavors in a Strawberry "out of season." An eminent English

authority (G. W. Johnson) in referring to that subject in a work

published some forty years ago, very truly says that "no

plant is more certain of producing a good crop, when forced, than is

the Strawberry, if properly treated; and none will more assuredly

disappoint the gardener's hope, after a fair promise, if he adopts

the too common error of forcing too fast." The Strawberry

naturally blooms in the spring when the nights are cool and the day

temperature far lower than later in the season; consequently, a

high temperature is neither required nor beneficial to plants when

first placed in the forcing house. Air should be admitted freely

during the night, and the temperature kept low until the plants

come into bloom, then an increase of several degrees is admissible,

but at no time is a very high temperature required.

The

larger varieties, such as Sharpless, Miner's Prolific, Seth

Boyden, Cumberland Triumph, and American Agriculturist, are all

excellent sorts for forcing, especially when extra size berries

are an object.

In

Europe forcing the Strawberry is practised more extensively than in

this country, but the demand for this fruit out of its natural season

is constantly increasing, and will, no doubt, continue to

increase for many years to come. Twenty-five years ago the Strawberry

season in our large cities scarcely extended beyond a period of six

weeks, but now it is nearly six months, for ripe Strawberries come

North from the Gulf States before the frost has left the ground in

the Northern, and before these two early berries reach us from the

South, those raised by forcing houses may be found in limited

quantities in our fruit stores. Of course, this early or forced

fruit commands a high price, but those who are able and willing to

pay for such luxuries should be, and are usually, accommodated.

FORCING

HOUSES.

Almost

any ordinary greenhouse may be used as a forcing house for the

Strawberry, provided it is so constructed that the plants can be

placed near the glass. If the plants are placed several feet below

the roof or glass, they are likely to be drawn, as it is termed, the

leaves and fruit-stalks growing tall and slender. Low houses are,

therefore, better for this purpose than high ones, and even

low-walled pits, heated by brick flues or earthen pipes, answer well

for forcing the Strawberry.

INSECT

ENEMIES.

Until

within the past decade or two the Strawberry was rarely injured —

at least not to any extent — by either insect or disease. But as

its cultivation is extended it naturally encounters a greater number

of enemies. Probably the most destructive pest is known under the

common name of White Grub, or larva of the May Beetle. There

are, however, over sixty distinct species of the May Beetle

inhabiting the United States, but, as their habits are very nearly

the same, they may for all practical purposes be considered as

one. There is scarcely a mile square of good arable land in the

United States that will not yield to the careful collector at least a

half dozen species of Lachnosterna or May Beetles. They are

more or less abundant in the Gulf States, and northward to Canada;

thence westward to California and along the entire Pacific

coast. These insects are usually more abundant in grass-lands,

prairies, meadows and pastures than elsewhere, as the principal food

of the grubs is the roots of grass and small herbs like the

Strawberry. They sometimes become so abundant in meadows and pastures

that, if such land is plowed up and planted with Strawberries, the

grab will destroy every plant almost as soon as it is put into the

ground. As these insects remain in the grub stage two or three years,

they consume a large amount of food, and they appear to prefer the

roots of the Strawberry to those of the common kinds of grasses.

Owing

to the wide distribution of these insects, and their almost universal

presence in old meadows and pastures, these lands should be

avoided whenever possible. If broken up and cultivated for a year or

two, or until the grubs have passed into the beetle stage, there can

be no objection to such lands if otherwise adapted to the

Strawberry. The female beetles usually resort to uncultivated

fields to deposit their eggs; consequently they are not likely to

become very abundant in those that are constantly kept under

cultivation.

The

Strawberry worm (Emphytus maculatus) is occasionally very

abundant and destructive. It is a small, slender, pale-green worm

about five-eighths of an inch long, attacking the leaves, eating

large holes in them at first, but eventually entirely denuding the

plant of foliage. Dusting the plants with lime when the leaves

are wet with dew, or with Paris green, will usually check this pest.

In

Canada And some of the Western States an insect known as the

Strawberry Leaf-Roller is occasionally quite abundant and

destructive. It is the larva or caterpillar of a small and handsome

moth, the Anchylopera fragaria. It is quite probable that

Paris green would be an effective remedy and might be safely used

after the fruit was gathered in summer.

There

are also several species of beetles that attack the crowns and stalks

of the Strawberry, and the common Strawberry Crown-borer

(Tyloderma fragaria) attacks the embryo fruit-stalks in the

spring, thereby destroying the most important organ of the

plants. The only remedy known is to immediately plow under the plants

and destroy the grubs while in an immature stage. In my own

experience, however, I have never, as yet, encountered an insect

enemy of the Strawberry which could not be readily vanquished by

clean cultivation and frequent renewal of the beds on

plantation.

|