| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2013 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

| CHAPTER

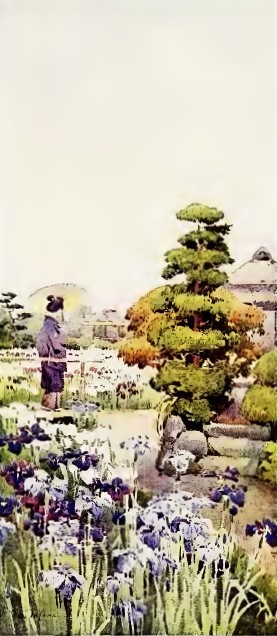

XII THE IRIS IF I were to be asked which of all the show gardens in Japan — a garden devoted to the cultivation of one especial flower — gave me most pleasure to visit, I should unhesitatingly answer Hon-kin, the garden of hana shobu or Iris Kæmpferi, in the neighbourhood of Tokyo. Throughout the month of June this garden remains a feast of subdued colour; for the iris is no gaudy, flaunting flower, but a delicate blossom shading from pure white, through every shade of mauve and lilac to rosy purple, and so deep a blue as to be almost black. In the first days of June the paths winding through the rice fields from the banks of the river Sumida will be crowded with sight-seers whose steps are all bent in one direction and with the same intent — to pay their annual visit to Hori-kiri; and throughout the month this never-ending stream continues from early dawn until the setting of the sun or the rising of the moon. Flower-sellers there will be too, one perhaps with only a modest bunch of half-opened buds in a wooden tub shaded from the sun by a large umbrella, not the unpicturesque object recalled to our English minds by the word umbrella, but one made of pale yellow paper, large and flat, with bamboo ribs, the owner's name inscribed in bold, black Chinese characters — or farther on a little stall decked with lanterns, and a gay-coloured curtain with some device suggestive of the iris; tiny toys, little fairy baskets of split bamboo with just one iris blossom, or fans painted with a giant bloom covering the whole fan, and other dainty trifles, to carry home to the little ones left at home or as a souvenir of this iris-land. The garden of Hori-kiri must be of very ancient date, as the fine old pine-trees, dwarfed and gnarled maple and juniper bushes, are not the growth of this generation, or even the last. The garden is said to date from some three centuries, and to be handed down from father to son, always in the same family. Nothing could be more perfectly laid out for the proper display of its especial flower, the shaping of the beds, the placing of the bridges, and even the colouring of the little summerhouses in which to entertain their host of guests — all has been thought out by this artistic family; and last, but by no means least, the clothing of the little maids who wait on them with untiring zeal — their kimonos and obis all harmonising in colour. I have lingered too long on the surroundings of the flowers, and the reader will want to know more of this wonderful flower which deserves so much attention — it does indeed deserve the attention, for surely by the middle of the "dew month" it is hard to imagine anything more beautiful than the scene which meets the eye. Some seventy varieties of this king of irises are grown, many raised from seed and jealously treasured by the owner of the garden. There are early and late varieties, three weeks almost between their time of flowering, but by the second week in June the second blooms of the early varieties will have opened and the first blooms of the later ones, so the effect is as if all were flowering together; every shoot of the plants seems to bloom; there are no gaps in their serried ranks. The mere variety is amazing. Some are pure white, only veined with a faint tinge of green; some have a margin of lilac; some are shaded; some mottled; but surely the most beautiful of all is just a great single bloom of one shade, be it white, lilac, or blue. Many people prefer the duplex flowers with an inner row of small petals, but to me this form seemed to have lost some of the natural beauty and grace of the true iris. I tried to learn something of their cultivation, hoping it might be of help to those who grow those poor specimens known in England as Iris Kæmpferi. It is not the plants themselves, or the varieties, which are at fault, for many thousands of roots leave the Hori-kiri garden every year to be scattered throughout the world, — it would seem to be the soil and climate which they resent and stubbornly refuse to adopt; for a few years they linger and even bravely flower, and then they begin to pine and droop like some poor home-sick mortal pining for his native land.  An Iris Garden August appears to be the especial month for dividing the roots or replanting them, so that month had better be chosen as the beginning of the iris year. The yellowing foliage is ruthlessly cut to half its natural height and the plants divided, for no clump is ever allowed to grow so large and old that it is hollow in the centre; the outer shoots appear to be the strongest, and have most promise of bloom for the following year. The beds are sunk a foot or so below the paths; and the rich soil is like a quagmire, not with standing water, but like swampy ground. In November the plants are all cut down, in preparation for the first dressing of manure in December. The liquid sewage is liberally applied, once towards the end of the year, and then again after an interval of a few weeks, the final dressing being given in January. By February the growth has started, and once the young leaves appear there can be no more manuring, or the foliage would suffer. From now until the time of flowering, the regulation of the irrigation seems to be the chief matter to ensure success in their cultivation. Each variety has its own especial name, generally with some poetical meaning, but difficult for the European ear to grasp, and I noticed that, no doubt for the sake of the foreign market, all the rows were numbered as well as named. Do not imagine that this is the only iris garden of Japan. There are many others, though I always think that Hori-kiri ranks first, not only for the beauty of the garden, but the actual flowers seem larger and better grown than anywhere else. Only a few minutes' drive from Hori-kiri will take you to Yoshino-en, celebrated for its wistaria as well as its irises. The ground is larger than Hori-kiri and the irises are well grown, but as the garden is not devoted entirely to their culture the effect is not so pleasing. The whole district almost seemed devoted to the culture of shobu — many, many fields of them I passed; but as they are grown entirely for the sake of cutting the blooms for market, there is never any mass of colour to be seen. The gardens at Kabata, belonging to the Yokohama Nursery Company, are perhaps the most extensive iris gardens in Japan; I felt almost dazzled and bewildered by the very size of the grounds — acres of irises — a beautiful sight; but I never derived the same pleasure from it as from the smaller garden. The iris is one of the few flowers which seems to be allowed to enter into the precincts of a true Japanese landscape garden: in many a private garden a stream will be diverted to feed an iris bed, placed where a piece of swampy ground would be most in keeping with the rest of the miniature landscape; or even the margin of a tiny lake will be utilised for just a few plants of shobu. I remember seeing an old priest tending his little colony of irises, which no doubt were chosen with great deliberation from a large collection for some especial beauty. How often have I seen an old man and woman considering on which particular favourite their few sen shall be expended, and then departing, the happy possessor of a new treasure to add to their little store. My friend the priest's collection all grew in pots; they did not look as though they would attain their full height and beauty; but as if to reward the loving care bestowed on them they all showed promise of flower; and no doubt in due time they will have been arranged so as to give the best effect and greatest pleasure to their grower. I asked a Japanese who, with his little gentle wife, was sitting in quiet contemplation and evident enjoyment of the scene, to tell me something of the flower as it appeals to the Japanese, and he said: "We live here in the choicest floral kingdom; and to our mind the flowers are beautiful, and we do not ask why or how, the sight of their beauty is far more real to us than any meaning which they may suggest. You will find no other nation like Japan, which loves Nature so truly in her varied forms and holds communion with all her aspects; we love the iris as a flower, but as nothing else. I cannot make my mind associate it with any meaning of zeal or chivalry, nor do I think of it as any messenger; it appeals to me only as a little quiet beauty of the water side, making friends with the sadness of the rainy season. In our poems the iris is almost inseparable from water; one of our celebrated poetesses has written the following seventeen-syllable poem —

Midzu

ga kaki,

Midzu ga kashikeri kakitsubata. (Water was the painter, Water again was the eraser Of the beautiful fleur-de-lis.)

"It is the universal custom throughout Japan to celebrate the fifth day of May by hanging bunches of shobu beneath the eaves of our houses, and to put them into the hot water of the public baths, as it is perfectly delicious for the bathers to inhale their odour. We also drink saké in which they have been steeped, on the same day. I felt proud to hear that the fleur-de-lis, as I believe you call the iris, is the national flower of France, as I like to think that it has found a home in the West, and when I was told that the flower which was put above Solomon's greatest glory was not the lily of our country, but that of the iris family, I felt glad and agreed with it." The delicate Iris Tectorum would be an immense addition to our English flower gardens, if only our summers were hot enough to bake their roots sufficiently to make them flower. I succeeded in making them grow; they threw up their shoots each year, but never one single flower, until at last, disgusted, I condemned them, like so many other treasures brought from foreign climes, as unsuited to our cold grey skies. Late in May these irises will be in full bloom and forming a purple spur on the top of the thatched straw roofs of the farmhouses; they are generally planted in this way (hence their name), and transform the roof ridge of many a peasant's dwelling into the aspect of a flower garden. Many different reasons are ascribed to their being planted in this manner; some say the irises are planted to avert the evil spirits, and there is a superstition that they are efficacious in the prevention of disease. There is also a legend that during one of the famines that devastated the land in olden days an order went forth that all cultivated land was to be given up to the growing of rice, but that the women of Japan, determined to save their iris roots, from which their powder (so essential to the toilette of every young Japanese lady) is made, planted them on the roofs of their houses. I give the tale with all due reserve, as I was never able to verify it, nor do I even know for certain that their precious gird is made from iris roots.

Other people no less positively affirm the growth to be accidental. Others, again, assert that the object is to strengthen the thatch. We incline to this latter view; bulbs do not fly through the air, neither is it likely that bulbs should be contained in the sods put on the top of all the houses in a village. We have noticed, furthermore, that in the absence of such sods, brackets of strong shingling are employed, so that it is safe to assume that the two are intended to serve the same purpose. (Chamberlain's Things Japanese.)

No matter the reason for their being so planted — be it for protection, be it for the sake of vanity or merely for safety — the effect is none the less charming, and later in the year these little roof gardens are sometimes gay with Hemerocallis aurantiaca or a stray tuft of scarlet Nerine. The true Iris japonica or chinensis is a shade-loving plant, with many lavender-coloured flowers on a branching stem, each outer petal marked with purple lines, and in the centre of the flower a deep orange horn. Like so many delicately marked flowers, it has a very short life, each individual bloom appearing to last only from one sunrise to the next, but the stems bear so many blooms that other buds quickly open and fill the gap of yesterday's blossom.  Irises

Iris gracilipes seems the commonest and most free-flowering of all the irises. In May its graceful purple flowers and vivid green grass-like foliage seemed to fringe each pond, and the only fault I had to find with this form of iris was the short duration of its flowering season; the plants bloom so freely they appeared to flower themselves to death, and after one short week their slender heads would hide themselves until the resurrection of the next "flower month." I learnt that the Iris lævigata, which appears to be synonymous with Kämpfer's iris, is much used as a decoration for ceremonies and congratulatory occasions, but on account of its purple colour it is not desirable for weddings, though permissible for betrothals. It is much honoured in the art of flower arrangement, and ranks high among the flowers used for the vase on the tokonoma; and the leaves are as much prized as the flowers, lending themselves to the bending and twisting required to attain the regulation curves. As a rule it is not permissible to use the leaves alone of a plant which may bear a flower, or the flowerless branches of a shrub which may bear blossoms or berries; but Iris japonica seems an exception to this rule, and the leaves alone may be used before the flowers appear. The first of the ten artistic virtues attributed to certain special combinations is headed in Mr. Conder's list by Simplicity — expressed by rushes and irises in a two-storey bamboo vase. The beautiful arrangement known as Rikkwa (double stump arrangement) consists of a combination of pine, iris, and bamboo grass. |