| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2013 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

| CHAPTER

V TEMPLE GARDENS OF all the gardens in Japan, and surely in no other country are there so many different forms of gardening, the temple garden, or often the garden surrounding some mouldering Buddhist monastery, remains a peaceful, secluded spot, recalling the Old Japan and days gone by. Unluckily many of them are fast falling into decay, like the buildings they surround; but perhaps it is better so, as they would surely suffer at the hands of the restorer, just as many of the temples have suffered; and though little may remain of the original gardens, the stones, beautified possibly by time, are still the same; the trees may have grown old and gnarled, but the form of the garden remains unchanged. It has been said that every good garden should be a "modulation from pure nature to pure art," and no one seems to have understood the saying better than the makers of these old temple gardens: they are always a setting for the building they surround, adding to its grandeur, never dwarfing it; the placing of every stone, the curve of every walk, the shape of the pond, all seem to have been duly weighed and considered, and the result is an harmonious whole. The grand Nikko temples, the shrines in Uyeno or Shiba, have been left in their natural surroundings; the tall grey masts of the cryptomerias stand like sentries to guard their precious treasure, the avenues broken only by long vistas of enormous steps or the uprights of a colossal granite torii. Nothing could be more imposing, and the effect of the bronze green of the cryptomerias against the splendid colour of the temple gives the crowning touch to a picture which in itself alone is worth travelling many thousand miles to see.

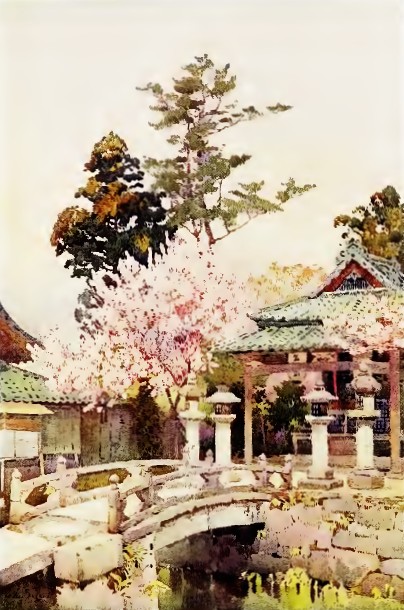

At Kitano Tenjin At Uyeno the cherry-trees reign all supreme, they do their full work; the mixing of other shrubs or trees would be unnecessary and meaningless; this is the simplest and yet the grandest form of gardening; a few large bronze lanterns and grey stones help to show off the delicate pink of the blossoms when they are in their glory, and yet seem to be part of the temple itself as no temple or shrine is complete without some of these beautiful votive offerings. At Nara, again, the cryptomeria forms the principal setting; in spring, many of the trees are wreathed with wistaria, the royal fuji, but this only helps to enhance their colour, and is suggestive of a grey misty vapour rather than a real flower, as often one sees no trace of the stem of the wistaria, and one wonders how the mass of mauve flowers has managed to appear suddenly at the very top of one of those giants of the forest. It is not around these large and world-renowned temples that one finds a garden, in the sense that we Europeans regard a garden, but rather in some peaceful spot which seems to have been overlooked by the hustle and bustle of the large town in which it may be situated. I am thinking now of one such garden in Kyoto; the evening bell seems to call you to come within its sanctuary, and once there one would surely never leave until the final closing of its great outer wooden door sends the loiterer away. It has an irresistible charm this tiny garden, hardly more than a toy compared to the scale of our English gardens, and it was no surprise to me to learn that it was planned to suggest in miniature the fabulous Garden of Paradise. One enters its outer precincts through one of those solid wooden gateways which seem so fitting to guard their charge, wood guarding wood, for remember all temples are made of wood in Japan; though many different kinds may be used, and the rarer and more beautifully veined pieces are brought together and collected from far and wide, still it is all wood, and for that reason the buildings seem to be especially in keeping with a garden.  The Drooping Cherry On either side of the gateway stand two old pine-trees, carefully trained and thinned at the proper season; but the most beautiful guardian is just within the gate, a grand old weeping cherry-tree, in April its boughs bent down by the weight of its blossoms, while its glory lasts for a week or two, casting a pinky light on all around. Even now you are only being prepared for the beauty to come, as you must knock on yet another little wooden door and ask permission of the acolyte to enter; he will offer to tell you the history of the garden in his peculiar sing-song note, suggesting a recitative, and utterly incomprehensible, unless you have thoroughly mastered his language. Seeing a foreigner he will probably reconcile himself to letting you wander at your will, and enjoy the beauties of this little haven of rest. We are told that the buildings were formerly magnificent, but have suffered from fire at the hands of the ronins, and in later days from accidental fires. What remains of the original building seems complete in itself, and one feels one would not have it otherwise. The garden was designed by the celebrated Kobori Enshu, and, like all his work, is much regarded and valued by the Japanese. The plan, roughly speaking, appears to be two ponds, a wooden bridge, and three tiny islands; but to the understanding one, they are the Crane and Tortoise ponds, the two small islands on the south being regarded as a crane, while the northern one is a tortoise. The wooden bridge is a Bridge of Heaven, and contains the Kwangetsudai, or Moon-gazing Platform, brought from the Momoyama Palace at Fushimi, where Hideyoshi is said to have used it for that purpose. All this is of deep interest to the Japanese; but to our eyes the charm of the garden lies in the fact that it is a little old-world garden full of repose, suggesting the Old Japan, and spots where foreign feet have seldom trod. I have known this garden at all seasons of the year. In February, when biting snow-showers remind one that winter is not yet over, the moss- and lichen-clad stones, the trim, clean-cut azalea and sweet box bushes, and the carpet of velvety moss in broad patches where the turf has not yet recovered from the winter frosts, are its only adornments. The pink buds of the one plum-tree it contains are fast swelling, and show you that spring's fairy raiment is being prepared by Nature; the buds of the large bush of flame-coloured Azalea mollis possibly the pride of the garden also help to give promise of future glories. Kodaiji was once famous for its cherry-trees, but now few remain, and we must content ourselves with its other treasures, which seem to bloom in one never-ending succession throughout the year. July is the only month in which I have never seen this garden, but I feel certain that even then there is no blank, something would spring up to be the pride of the garden. In March her one plum-tree reigns supreme, in April the cherry blossom; in May the Crane pond is fringed with purple irises, and the gorgeous azalea casts its reflection also; in June the later Azalea indica.... flower as best they can, but how many of their buds fall victims to the gardener's shears. In July the lotus leaves in both the ponds are already getting taller every hour, and in the early hours of some morning late in July the first lotus bud will open with a crack and gradually unfurl its beautiful pink or white blossom. All through August fresh buds will appear, and indeed well into September, when at last the leaves will begin to curl and shrivel, and one can only wonder how they stood the scorching heat of the sun all through those long weeks. By the beginning of October the leaves of the maples will be turning, gradually growing more and more fiery in colour as the month dies out, till in November they are in all their gaudy splendour, and Kodaiji is noted for its momiji. The priest, too, who evidently loves his garden, has by now moved with tender care his chrysanthemum plants, whose pots have been kept from the sun's fiercest rays, and never allowed to cry out for water, and placed them in one of those curiously fragile little structures which seem to exist only for the protection of chrysanthemums, with a roof more suggestive of a chess-board than anything else, and arranged them in front of his dwelling-room, so that he can sit and gaze at them, just as in old days Hideyoshi sat on the neighbouring platform to gaze at the moon. Do not imagine that when the last maple falls, or the last kiku flower is cut, the year is over in this favoured little spot, for in December the Camellia Sasanqua holds its own against frost and even snow; its lovely rose-coloured flowers, which with their yellow stamens, are more suggestive of the blooms of Penzance briar roses than of camellias, are in sharp contrast with the deep glossy foliage, and seem more fitted for a spring flower than one for the dying year.

A Shrine at Kyomidzu It is not always easy for the foreigner to obtain permission to visit some of these secluded and hallowed spots. I can recall a long rough ricksha drive in the environs of Kyoto, through somewhat uninteresting country, consisting of endless miles of rice-fields Hiezan, it is true, forming a beautiful background; but though I was armed with credentials which I was assured would gain me admission to a veritable holy of holies, a garden so old that no one knew its origin, my enthusiasm was beginning to wane when we arrived within some large rambling temple grounds. We asked to see the garden, and were bowed into a not very interesting and rather uncared-for court, but I felt this could not be the spot I had come so far to see; besides, admission had been too readily granted; it would require patience and perseverance to find this inner sanctuary. After many explanations and many times being assured there was no other garden, we were eventually directed to the priest's private dwelling, and then I knew my chance had come, as an especially holy man was the owner of the precious little garden. I was greeted with a look of horror and incredulity: "Was it possible that the foreigner had even penetrated within these mouldering monastery grounds?" The permission was granted, and I entered the spotlessly clean white-matted rooms, which all looked on the garden. First a little forecourt, and beyond, the sacred spot. At the first glance what did it consist of? A few stone lanterns, almost diminutive in size, to be in  White Cherry at Kitano keeping with the rest of the garden; some so buried in velvety moss that their shape seemed almost altered by the thickness of their green canopy; a few curiously shaped and fantastic stones, also with their covering of grey lichen and moss; some old gnarled and twisted shrubs, and two or three little toy stone bridges. Not a single flower to break the severity of the outline. The garden lay in a pine wood, and at first I thought, "How curious that a spot so evidently well cared for should be carpeted thickly with pine needles!" Never had I seen stone bridges placed where there was no water to cross; the only water in the garden appearing to be a tiny little ceaseless trickle in the beautifully shaped water-basin, which stands at the entrance to nearly all Japanese gardens, however small; but presently I noticed that the pine needles only covered the actual ground, not one was lying on the little rising mound or lodging in any bush, and then I realised the cleverness, the ingenuity of the idea the pine needles represented the water; each spine seemed to be in its place under the little bridge; they came perfectly smooth and always following each the same way like flowing water. Presently some projecting point or little island in this fancy lake would break their regularity, and they would be turned and twisted to represent the current of the water. It took one's breath away. "Who ever had the patience to arrange this carpet?" It seemed almost as if it might be the work of some one undergoing a penance, being condemned to keep these pine needles in perfect order; one puff of wind might mean hours of work to their guardian. I felt that my perseverance had been well repaid, as during all my wanderings in Japan I never came across another example of that style of gardening, nor was I ever able to obtain the real history of this garden. The gardens round the smaller temples seem generally to be in the special care of some old priest. Many of them unfortunately are fast falling into decay, and are often neglected; but many are evidently the pride and joy of their owner, who usually seems much gratified by the admiration they evoke. Often only a very small piece is kept in anything like trim and formal order, and then one wanders up the hill and finds a different scene nature running riot, helped by a minute mountain stream, as an unceasing supply of moisture seems almost more necessary to the vegetation of Japan than to that of any other country; but still the path winds on, and the wanderer is impelled to see where it will lead him to. The end is always the same, some silent graveyard perhaps only a score or so of memorials of the dead, or perhaps hundreds, or even it would seem almost thousands, of these ghostly moss-blackened monuments, jostling each other, so crowded are they, hardly any two alike in size or shape, leaning all of them, suggesting endless earthquakes, but mostly with a section of bamboo in front of them to hold a branch of evergreen or flower, showing that some one still remembers the departed one, and loving hands light the humble incense bowl. Perhaps one of the most elaborate gardens I ever saw was that of Sampo-in, on the way to Otsu. Here one feels as if the work of man had almost distorted nature, if such a thing were possible, and yet the picture would be poor indeed were it not for its splendid setting of forest trees. Again a giant weeping cherry stands like a guardian within the gate, and then you pass on; and never have I seen trees so fantastically twisted into the most impossible angles and shapes. The keynote of the garden seems to be the lilliputian mountain torrent, for does not that give a raison d'κtre for the stone or turf bridges which are flung across it to connect the mossy banks with the diminutive islands, on one of which stands a celebrated pine, twisted, and torn, and cut, so that it has lost all trace of what nature intended it to be, but surely not lost all charm. In this garden also there are no flowers, only little trespassers. I noticed numbers of little wild flowers nestling in the shadow of the bridges or between the mossy rocks, seeming to pray to be left undisturbed by the ruthless weeder. The pride of this especial garden was its maples. When I saw it, they had not yet lost the red glow in which their leaves unfurl in spring; but in November they would doubtless be better still, and the garden illuminated by a blaze of colour. On leaving, it seemed impossible to avoid marring the patterns traced in the silver sand, patterns of a thousand years ago. Round some of the larger and more imposing temples and monasteries the ground is less a garden than a pleasaunce, for the little miniature gardens I have described would be no fitting framework, for instance, for that noble building the Chion-in in Kyoto, whose grounds include some sixty acres on the wooded slope of those hills which form an unrivalled background to the fairest city of Japan. So large an extent could not possibly be broken up and formed into a garden such as I have already described; the effect would be grotesque and all sense of true proportion lost. How imposing is the great gate standing in its setting of pines, in spring softened by the cherry blossom which shows here and there between them. A long dizzy flight of stone steps leads up to the main building of the temple. Here the ground has been levelled, the work of many thousand hands, it being no petty task to level a plateau large enough for the main building of this mighty edifice, some 146 feet long and 114 feet wide. Hardly less imposing is the assembly hall or room of a thousand mats, surrounded by a wooden corridor so constructed that in walking round it there is produced a sound which is thought to resemble the singing of the uguisu, the Japanese nightingale, and there is yet another grand hall, the Dai Hojo. How grandly and simply the grounds of this temple are adorned. The large square in front of the main building has for its chief adornment two stone lanterns of colossal size, and the celebrated bronze water-basin in the form of a lotus leaf, from whose lip runs a ceaseless stream of clear water brought from the hill above. A few specially beautiful cherry-trees and some grand old pines, leaning most of them, but all the more beautiful for that reason, surround this square, and form a fitting setting to that massive pile. Yet another flight of steps leads to the bell-tower also a fitting guardian, as more than once the thundering of this mighty bell has summoned all who revered their beloved Chion-in to come and protect it from an imminent danger of fire.  Cherry Blossom, Chion-in Temple The Japanese are great respecters of legends, which may make a tree or stone sacred for all time. The Melon Rock, Kwasho Seki, has been so called from the story that a melon plant sprouted out from beneath the rock and grew so rapidly that in a single night it had covered the whole rock, blossomed, and borne fruit. Many hundred sight-seers trail during their weary tramp to gaze with awe at this plain grey stone inscribed with the characters of Gozu Tenno or Bull-head Emperor, and we in our turn cannot fail to gaze with respect at their simple faith. |