| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2008 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

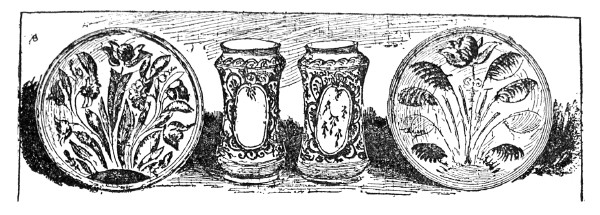

CHAPTER XI EARLY AMERICAN POTTERS THE history of American ceramics tells a story of slower development than that of most of the other industrial arts. Building bricks were made in Virginia as early as 1612, and in New England about 1641; coarse earthenware was made in several places late in the seventeenth century; white ware was first manufactured at Burlington, New Jersey, about 1684; terra cotta roofing tiles were made in Pennsylvania prior to 1740. But no pottery of any consequence was made here till after the middle of the eighteenth century and the most significant part of the history lies within the nineteenth century. Hard porcelain was not manufactured in America till 1825. During Colonial and Revolutionary times tableware was imported from England, France, and China, and it is for that reason that most of our collecting has been of English, Canton, and Sèvres wares. Staffordshire tableware especially was made in large quantities for the American market, and it was apparently difficult, with this competition, for American manufacturers to get a foothold. Nevertheless, with the awakening interest in American antiquities, greater attention is now being paid to such early American pottery as exists. Thus far the demand has been for Bennington and other of the later wares, but the Pennsylvania slip-decorated ware and some of the earlier pottery is now coming to the front. Little or nothing is known of the potters who operated the small kilns that turned out the coarse domestic earthenware of the seventeenth century. Previous to 1649 there were a number of such humble potters in Virginia, and the Dutch settlers of Manhattan produced a ware not unlike Delft. In 1683 a potter and glassmaker by the name of Joshua Tittery came to Pennsylvania to practice his art, and in 1690 there was at least one potter and one maker of clay tobacco pipes in Philadelphia. In New England John Pride of Salem was registered as a potter as early as 1641, and soon after there was a flourishing brick and tile works at Danvers. Here William Osborne started in business and for two centuries he and his descendants carried on the manufacture of plain earthenware or red clay pottery. About 1684, Dr. Daniel Coxe of London, one of the proprietors and later Governor of West New Jersey, caused a pottery to be erected at Burlington, New Jersey, which was conducted by John Tatham, his agent, and Daniel Coxe, Jr., his son. They were probably the first to make whiteware in the Colonies. For fifty years the industry seems to have been more or less at a standstill, though the obscure makers of plain earthenware continued to flourish in many parts of the country. Then, in 1735, John Remmey, a German, started a stoneware factory in New York. This business was continued by three generations of John Remmeys and was discontinued about 1820. In 1742 the firm name of Remmey & Crolius appears, and after 1762 Clarkson Crolius conducted a similar business on his own account. Perhaps the most interesting of all the early American pottery is the slip-decorated and sgraffito ware made in eastern Pennsylvania from about the middle of the eighteenth century, or possibly before that, until well into the nineteenth. This ware was made chiefly by Germans who brought their methods and designs with them from the Rhine. There were a few English potters among them, undoubtedly, but dishes bearing English legends are very rare. The Pennsylvania Museum has collected a large number of good examples of the ware, which has recently be gun to attract the attention of private collectors as well. The slipware is a common red, brown, or buff pottery upon which the decoration was applied in the form of a clay batter poured through a quill and al lowed to dry before firing. This "slip" was cream colored, or tinted green, blue, pink, etc. The designs consisted of crude representations of men and women, birds, beasts, and flowers — the tulip predominating — executed in a sort of futurist style and often accompanied by dates, names, and legends. Cooking pots, vinegar and molasses jugs, jars, tea caddies, mugs, pitchers, coffee pots, sugar bowls, pie plates, meat and vegetable dishes, bowls, and toys were made in this ware. The sgraffito was a similar earthenware, coated with a lighter-colored slip, in which the decorations were scratched or incised, exposing the darker body below. A transparent glaze was then applied, and after the final firing the ware showed a greenish mottled surface with dark red intaglio decorations. A number of small potters appear to have been engaged in this industry, some of them perhaps being farmers who employed their winter months in this way. One of the earliest on record was an Englishman, Joseph Smith, who made pottery at Wrightstown, Bucks County, Pennsylvania, as early as 1763. George Hübener, in Montgomery County, was the creator of some of the most elaborate designs made prior to 1786. Toward the end of the century some of the best of the ware was made by John Leedy, near Souderton, Montgomery County. His tulip designs were particularly good. One of the Germans who appears to have attained considerable prominence in this trade early in the nineteenth century was Johannes Neesz. He operated a pottery near Tyler's Port, Montgomery County, about four miles from Souderton. He manufactured plates, mugs, vegetable dishes, etc., in both slip and sgraffito ware, and also clay toys. One or two pieces of his finer work at the Pennsylvania Museum show him to have been a craftsman of no small ability, and his decoration was always more finished and in better drawing than that of most of his contemporaries. His son, also a potter, changed the spelling of the name to John Nase. David Spinner, a potter from before 1800 until 1811, on Willow Creek, Milford Township, Bucks County, enjoyed considerable local fame. His father, Ulrich Spinner, came to America from Zurich, Switzerland, in 1739. A number of Spinner's signed pieces are in existence and they include some of the most interesting examples of Pennsylvania-German pottery. He used a variety of flower motifs, the fuchsia being a favorite with him. His pictorial treatments were more ambitious than those of most of his contemporaries and were better drawn. They included gay and courtly ladies and gentlemen, gallant soldiers, and spirited hunting scenes. Dr. Barber gives, all told, the names of twenty-two of these potters, the majority of which are German names. There is still a possibility of picking up this ware in Eastern Pennsylvania, and a few pieces have already found their way to the shops of dealers. They are worth anywhere from $1 up, and the values are bound to increase with the demand. A neighbor of mine recently paid $25 for an unsigned slip-decorated plate bearing a peacock and the date 1788. During

the last half of the eighteenth century cups and saucers, plates,

platters, pitchers, bean pots, and jugs of coarse earthenware were

being produced in increasing quantities. In 1751 Edward Annely of

Whitestone, Long Island, advertised flower pots, garden urns, etc. At

about the same time a pottery was started at Huntington, Long Island,

by a man named Scudder for the manufacture of earthenware and

salt-glazed stoneware. In 1775 the Huntington works passed into the

hands of one Williams, and were continued under various proprietors

until 1903. From the middle of the century until 1823 an earthenware

pottery was operated by Thomas, John, and Paxson Vickers,

successively, at west Whiteland, Chester County, Pennsylvania. From

1791 to 1811 John Curtis made a good quality of pottery in

Philadelphia.

In New England, particularly in Connecticut, there were several thriving earthenware potteries. As early as 1760 a pottery and glass works had been established by Joseph C. Palmer and Richard Cranch at Germantown, now a suburb of Quincy, Massachusetts. About 1765 Abraham Hews started at Weston, Massachusetts, a pottery for the manufacture of earthenware milk pans, bean pots, jugs, pudding dishes, etc. He appears to have been a man of some prominence in his community, serving as postmaster for fifty-one years. Later the pottery became famous for terra cotta jardinières, garden vases, etc. Abraham Hews died at the age of eighty-eight, when his son moved the works to North Cambridge, where the business has been con ducted continuously ever since by the grandson and great-grandson. In 1796, C. Potts & Son perpetrated an unintentional pun by starting an earthenware pottery on Bean Hill, Norwich, Connecticut. In 1775 a potter named Upton went from Nantucket to East Greenwich, Rhode Island, and made plates, cups, saucers, and bowls of red clay. In 1793 there was a flourishing pottery at Quasset, Windham County, Connecticut, conducted by Thomas Bugbee. He made bean pots, jugs, jars, milk pans, and ink-stands which he peddled about the country. A little later Adam States of Stonington, Connecticut, made red earthenware and also gray jugs, jars, and pots with a salt glaze. A factory at Norwalk made mugs, teapots, jars, and milk pans of red ware with a lead glaze, and also stoneware as early as 1780, and in 1790 John Stouter started an earthenware enter prise in Hartford. In 1793 John and William Norton went from Connecticut to Bennington, Vermont, and started the red earthenware works that later developed into the famous Bennington potteries. At Morgantown, West Virginia, slip-decorated ware and lead-glazed pottery were made prior to 1785 by a man named Foulke, who was succeeded about 1800 by his foreman, John W. Thompson. Some of Thompson's ware was interesting in form and beautifully colored. The first attempt to manufacture fine china in the Colonies was in 1769, when a pottery was erected for the purpose in Philadelphia by Gousse Bonnin and George Anthony Morris. They made bone china and cream-colored ware, both plain and decorated in blue. It is not likely that they attempted to make real porcelain. The works were run for two years and were then closed. In the same year, 1869, efforts were made to start and maintain a china factory in Boston. Apparently this proved abortive, but the attempt attracted the attention of English potters who began coming to America. In 1774 and 1775 Jonathan Durell of New York advertised "butter, water, pickle and oyster pots, porringers, milk pans of several sizes, jugs of several sizes, quart and pint mugs, quart, pint, and half pint bowls, of various colours, small cups of different shapes, striped and coloured dishes of divers colours, pudding pans and wash basins, sauce pans, and a variety of other sorts of ware, too tedious to particularize, by the manufacturer, late from Philadelphia." With the beginning of the nineteenth century there were many other potters in the field and it will be necessary to mention only the more important enterprises. Philadelphia became the center of the industry. Here Andrew Miller, who had conducted a pottery On Sugar Alley since 1791, was succeeded in 1810 by Abraham Miller, one of the most progressive potters of his day. At his factory at Seventh and Zane Streets he undertook the manufacture of glazed wares, soft-paste porcelain, white ware, Rockingham, and silver luster. He was a prominent citizen, being a leading member of the Franklin Institute and representing his district in the State Senate. In

1808, Binney & Ronaldson made red and yellow coffee and tea

sets

in South Street. From 1808 to 1813 the Columbian Pottery, Alexander

Trotter proprietor, manufactured tea and coffee pots, pitchers,

basins, ewers, and baking dishes, also jugs and goblets of

queensware. From 1808 the Washington Pottery, John Mullawney

proprietor, made bricks and earthenware. David Freytag was making

fine decorated china in 1811 and George Benorton in 1817, and from

1817 to 1822 David G. Seixas made white crockery. In 1812, Thomas

Haig, who came from Scotland, where he had learned his trade as a

queensware potter, started the Northern Liberties Pottery and turned

out an excellent quality of glazed red and black earthenware

— teapots, coffee pots, pitchers, strainers, cake molds, and

pans.

During the first quarter of the century successful potteries were established also in New York, Albany, Troy, Utica, Baltimore, Lancaster, Pittsburg, Allentown, Elizabeth, New Jersey, Middlebury, Vermont, and Jaffrey, New Hampshire. The term antique can hardly be applied to pottery and china made after 1825, yet there are certain wares and factories of later period that are of interest to the collector and to the student of the history of American ceramics. In 1825 the Jersey Porcelain and Earthenware Company was incorporated and erected a factory in Jersey City. For two or three years soft-paste porcelain was made here. The works were purchased by D. & J. Henderson about 1829, and stone ware was manufactured. In 1833, David Henderson organized the American Pottery Manufacturing Company, which turned out a variety of wares, having chiefly a buff body of excellent quality, and including the first transfer-printed china made in this country. Some of the pitchers made by this company are especially sought by collectors, particularly toby pitchers, 1840 campaign pitchers, and the Greatbach hound-handled pitcher which was later improved upon at Bennington. A large portion of the product of this factory was marked with its name. After 1850 the establishment became known as the Jersey City Pottery. Most

important of all the developments of the second quarter of the

century was the work of William Ellis Tucker and his American China

Manufactory in Philadelphia. To him is due the credit of making the

first American hard porcelain on a successful commercial scale. He

was the son of Benjamin Tucker who kept a china shop on Market Street

from 1816 to 1822. In the rear of this shop a small kiln was built

for the use of the son in decorating the imported china. He began

experimenting with various materials in this kiln, and about 1825 he

undertook the manufacture of porcelain as a business venture. In

spite of failures and discouragements he persisted until he was

turning out a very fair grade of porcelain.

After the death of William Tucker in 1832, the business was continued by his brother, Thomas Tucker, in partnership with Judge Joseph Hemphill. They imported foreign artists and began to devote a good deal of attention to form and decoration. They turned out a great variety of ornamental and utility ware which enjoyed a considerable vogue among the well-to-do people of Pennsylvania and New Jersey. Some of the vases, pitchers, and table pieces were close copies of Sèvres forms, and as many of them are unmarked they are often mistaken for French porcelain. The business did not prove a complete success financially and was discontinued about 1838. A similar ware was made in Philadelphia about 1830 by Smith, Fife & Co. The pottery at Troy, Indiana, is interesting chiefly because it was started by James Clews, the eminent potter of Cobridge, England, who made some of the American views familiar to collectors of old blue Staffordshire ware. He came to this country after closing his English works in 1829 and, with a number of capitalists, incorporated the Indiana Pottery Company in 1837. Though started under the best of auspices, this factory was never conspicuously successful. Blue, yellow, and Rockingham wares were made here, but nothing of superior excellence. Mr. Clews returned to England, where he died in 1856, and the business led a desultory existence for a few years longer. Mr. Clews was a skilled and enter prising potter and deserved better success here. He was the father of Henry Clews, the New York banker. Charles Cartlidge was another potter of unusual ability who came from England, where he had worked for William Ridgway. With a Mr. Ferguson he organized the firm of Charles Cartlidge & Co. and started a pottery at Greenpoint, Long Island, in 1848. They first made porcelain buttons, and later a fine quality of decorated table china, bone porcelain tea sets, pitchers, bowls, ornaments, door plates, door knobs, curtain knobs, etc., besides some very excellent jewelry cameos and portrait busts in biscuit porcelain. Cartlidge was a man of artistic instincts and employed the best talent he could find. His chief de signer and modeler was his brother-in-law, Josiah Jones, who executed some beautiful portrait busts and ornamental ware. Other skilled decorators employed by him were Elijah Tattler and Frank Lockett. A group of Bennington pottery in the Pitkin Collection at the Hartford Athenæum, showing Rockingham and parian ware, figures and pitchers. Here are the poodles, cow creamers, a toby, the exquisite figure in parian of the girl tying her shoe, and the famous hound-handled pitcher

The factory was closed in 1856 and Mr. Cartlidge died in 1860. He was prominent in his community, a leading churchman, and an authority on church music. I know of no special attempt having been made to collect Cartlidge china, but it would certainly repay the effort. Pottery enterprises were also started previous to 1850 in New York, Philadelphia, New Brunswick, New Jersey; South Amboy, New Jersey; Louisville, Kentucky; Strasburg, Virginia; at East Liverpool, Ohio, where American Rockingham ware was first made by James Bennett in 1839; and at Bennington, Vermont, where Christopher Fenton started his famous pottery in 1846 and began the production of the first American parian ware. |