|

1999-2004 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click Here to return to Birds Every Child Should Know Content Page Click Here to return to last Chapter |

(HOME) |

|

1999-2004 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click Here to return to Birds Every Child Should Know Content Page Click Here to return to last Chapter |

(HOME) |

|

CHAPTER XV

DAY AND NIGHT ALLIES OF THE FARMER TURKEY VULTURE RED-SHOULDERED HAWK RED-TAILED HAWK COOPER'S HAWK BALD EAGLE AMERICAN SPARROW HAWK AMERICAN OSPREY AMERICAN BARN OWL SHORT-EARED OWL LONG-EARED OWL BARRED OWL SCREECH OWL TURKEY VULTURE Called also: Turkey Buzzard EVERY child south of Mason and Dixon's line knows this big buzzard that sails serenely with its companions in great circles, floating high overhead, now rising, now falling, with scarcely a movement of its wide-spread wings. In the air, it expresses the very poetry of motion. No other bird is more graceful and buoyant. One could spend hours watching its fascinating flight. But surely its earthly habits express the very prose of existence; for it may be seen in the company of other dusky scavengers, walking about in the roads of the smaller towns and villages, picking up refuse; or, in the fields, feeding on some dead animal. Relying upon its good offices, the careless farmer lets his dead pig or horse or chicken lie where it dropped, knowing that buzzards will speedily settle on it and pick its bones clean. Our soldiers in the war with Spain say that the final touch of horror on the Cuban battlefields was when the buzzards, that were wheeling overhead, suddenly dropped where their wounded or dead comrades fell. Because it is so helpful in ridding the earth of decaying matter, the law and the Southern people, white and coloured, protect the vulture. Its usefulness is more easily seen and understood than that of many smaller birds of greater value which, alas! are a target for every gunner. Consequently, it is perhaps the commonest bird in the South, and tame enough for the merest tyro in bird lore to learn that it is about two and a half feet long, with a wing spread of fully six feet; that its head and neck are bare and red like a turkey's, and that its body is covered with dusky feathers edged with brown-an ungainly, unlovely creature out of its element, the air. Another sable scavenger, the black vulture or carrion crow, of similar habits, but with a more southerly range, is common in the Gulf States. Because it feeds on carrion that not even a goat grudges it, and is too lazy and cowardly to pick a quarrel, the buzzard has no enemies. Although classed among birds of prey, it does not frighten the smallest chick in the poultry yard when it flops down beside it. With beak and claws capable of gashing painful wounds, it never uses them for defence, but resorts to the disgusting trick of throwing up the contents of its stomach over any creature that comes too near. When a colony of the ever-sociable buzzards are nesting, you may be very sure no one cares to make a close study of their young.

RED-SHOULDERED HAWK

Called also: Hen Hawk; Chicken Hawk; Winter Hawk Let any one say "Hawk" to the average farmer and he looks for his gun. For many years it was supposed that every member of the hawk family was a villain and fair game, but the white searchlight of science shows us that most of the tribe are the farmers' allies, which, with the owls, share the task of keeping in check the mice, moles, gophers, snakes, and the larger insect pests. Nature keeps her vast domain patrolled by these vigilant watchers by day and by night. Guns may well be turned on those blood-thirsty fiends in feathers, Cooper's hawk, the sharp-shinned hawk, and the goshawk, that not only eat our poultry, but every song bird they can catch: the law of the survival of the fittest might well be enforced with lead in their case. But do let us protect our friends, the more heavily built and slow-flying hawks with the red tails and red shoulders, among other allies in our ceaseless war against farm vermin! In the court of last appeal to which all our hawks are brought-I mean those scientific men in the Department of Agriculture, Washington, who examine the contents of birds' stomachs to learn just what food is taken in different parts of the country and at different seasons of the year-the two so-called "hen hawks" were proved to be rare offenders, and great helpers. Two hundred and twenty stomachs of red-shouldered hawks were examined by Dr. Fisher, and only three contained remains of poultry, while one hundred and two contained mice; ninety-two, insects; forty, moles and other small mammals; fifty-nine, frogs and snakes, and so on. The percentage of poultry eaten is so small that it might be reduced to nothing if the farmers would keep their chickens in yards instead of letting them roam to pick up a living in the fields, where the temptation to snatch up one must be overwhelming to a hungry hawk. Fortunately these two beneficent "hen hawks," are still common, in spite of our ignorant persecution of them for two hundred years or more. Toward the end of summer, especially in September, when nursery duties have ended for the year and the hawks are care free, you may see them sailing in wide spirals, delighting in the cooler stratum of air high overhead. Balancing on wide, outstretched wings, floating serenely with no apparent effort, they enjoy the slow merry-go-round at a height that would make any child dizzy. Sometimes they rise out of sight. Kee you, kee you, they scream as they sail. Does the teasing blue jay imitate the call for the fun of frightening little birds? But the red-shouldered hawk is not on pleasure bent much of the time. Perching is its specialty, and on an outstretched limb, or other point of vantage, it sits erect and dignified, its far-seeing eyes alone in motion trying to sight its quarry-a mouse creeping through the meadow, a mole leaving its tunnel, a chipmunk running along a stone wall, a frog leaping into the swamp, a gopher or young rabbit frisking around the edges of the wood-when, spying one, "like a thunderbolt it falls." If you could ever creep close enough to a red-shouldered hawk, which is not likely, you would see that it is a powerful bird, about a foot and a half long, dark brown above, the feathers edged with rusty, with bright chestnut patches on the shoulders. The wings and dark tail are barred with white, so are the rusty-buff under parts, and the light throat has dark streaks. Female hawks are larger than the males, just as the squaws in some Indian tribes are larger than the braves. It is said that hawks remain mated for life; so do eagles and owls, for in their family life, at least, the birds of prey are remarkably devoted, gentle and loving.

RED-TAILED HAWK

Called also: Hen Hawk; Chicken Hawk; Red Hawk This larger relative of the red-shouldered hawk (the female red-tail measures nearly two feet in length) shares with it the hatred of all but the most enlightened farmers. Before condemning either of these useful allies, everyone should read the report of Dr: Fisher, published by the Government, and to be had for the asking. This expert judge tells of a pair of red-tailed hawks that reared their young for two successive seasons in a birch tree in some swampy woods, about fifty rods from a poultry farm, where they might have helped themselves to eight hundred chickens and half as many ducks; yet they were never known to touch one. Occasionally, in winter especially, when other food is scarce, a red-tail will steal a chicken-probably a maimed or sickly one that cannot get out of the way-or drop on a bob-white; but ninety per cent. of its food consists of injurious mammals and insects. Both of these slandered "hen hawks" prefer to live in low, wet, wooded places with open meadows for hunting grounds near by.

COOPER'S HAWK

Called also: Chicken Hawk; Big Blue Darter Here is no ally of the farmer, but his foe, the most bold of all his robbers, a blood-thirsty villain that lives by plundering poultry yards, and tearing the warm flesh from the breasts of game and song birds, one of the few members of his generally useful tribe that deserves the punishment ignorantly meted out to his innocent relatives. Unhappily, it is perhaps the most common hawk in the greater part of the United States, and therefore does more harm than all the others. It is mentioned in this chapter that concerns the farmers' allies, only because every child should know foe from friend. The female Cooper's hawk is about nineteen inches long and her mate a finger-length smaller, but not nearly so small as the little blue darter, the sharp-shinned hawk, only about a foot in length, but which it very closely resembles in plumage and villainy. Both species have slaty-gray upper parts with deep bars across their wings and ashy-gray tails The latter differ in outline, however, Cooper's hawk having a rounded tail with whitish tip, and the sharp-shinned hawk a square tail. In maturity Cooper's hawk wears a blackish crown. Both species have white throats with dark streaks and the rest of their under parts are much barred with buff and white. Instead of spending their time perching on lookouts, as the red-tailed and red-shouldered hawks do, these two reprobates dash after their victims on the wing, chasing them across open stretches where such swift, dexterous, dodging flyers are sure to overtake them. Or they will flash out of a clear sky like feathered lightning and boldly strike a chicken, though it be pecking corn near a farmer's feet. These two marauders, and the big slate-coloured goshawk, also called the blue hen hawk or partridge hawk, stab their cruel talons though the vitals of more valuable poultry, song and game birds, than any child would care to read about.

BALD EAGLE

Every American boy and girl knows our national bird, which is the farmer's ally, however, only when it appears on the money in his pocket. Without an eagle on that, you must know it would be of little use to him. Truth to tell, this majestic emblem of our republic (borrowed from imperial Rome) that spreads itself gloriously over our coins, flag poles, public buildings and government documents, is, in real life, not the bravest of the brave, nor the most intelligent, nor the noblest, nor the most enterprising of birds, as one fain would believe. On the contrary, it often uses its wonderful eyesight to detect a bird more skilful than itself in the act of catching a fish, and then puts forth its superb strength to rob the successful fisher of his prey. The osprey is a frequent sufferer, although some of the water fowl, that patiently course over the waves hour after hour, in search of a dinner, may be robbed of it by the overpowering pirate. Dead fish cast up on the beach are not rejected. When fish fail, coots, ducks, geese and gulls -- the fastest of flyers -- are likely to be snatched up, plucked clean of their feathers, and torn apart by the great bird that drops suddenly upon them from the clouds like Jove's thunderbolt. Rarely small animals are seized, but there is probably no well-authenticated case of an eagle carrying off a child. It is in their family life that hawks and eagles, however cruel at other times, show some truly lovable traits. Once mated, they know neither divorce nor family quarrels all their lives. Home is the dearest spot on earth to them. They become passionately attached to the great bundle of trash that is at once their nest and their abode. A tall pine tree, near water, or the rocky ledge of some steep cliff, is the favourite site for an eagle eyrie. Here the devoted mates will carry an immense quantity of sticks, sod, cornstalks, pine twigs, weeds, bones, and other coarse rubbish, until, after annual repairs for several seasons, the broad, flat nest may grow to be almost as high as it is wide and look something like a New York sky-scraper. Both parents sit on the eggs in turn and devote themselves with zeal to feeding the eaglets. These spoiled children remain in the nest several months without attempting to fly, expecting to be waited upon even after they are actually larger than the old birds. The castings of skins, bones, hair, scales, etc., in the vicinity of a hawk's or eagle's nest, will indicate, almost as well as Dr. Fisher's analysis, what food the babies had in their stomachs to make them grow so big. Immature birds are almost black all over. Not until they are three years old do the feathers on their heads and necks turn white, giving them the effect of being bald. Any eagle seen in the eastern United States is sure to be of this species. In the West and throughout Asia and Africa lives the golden eagle, of which Tennyson wrote the lines that apply equally well to our Eastern "bird of freedom":

AMERICAN SPARROW HAWK

Called also: Killy Hawk; Rusty-crowned Falcon; Mouse Hawk Just such an extended branch as a shrike or a kingbird would use as a lookout while searching the landscape o'er for something to eat, the little sparrow hawk chooses for the same purpose. He is not much larger than either of these birds, scarcely longer than a robin. Because he is a hawk, with the family possession of eyes that are both telescope and microscope, he can detect a mouse, sparrow, garter snake, spider or grasshopper, farther away than seems to us possible. Every farmer's boy knows this beautiful little rusty-red hawk, with slaty-blue cap and wings, and creamy-buff spotted sides, if not by sight then by sound, as it calls kill-ee, kill-ee kill-ee, across the fields. It does not soar and revolve in a merry-go-round on high like its cousins, but flies swiftly and gracefully, keeping near enough to the ground to see everything that creeps or hops through the grass. Dropping suddenly, like a stone, upon its victim (usually a grasshopper) it seizes it in its small, sharp, fatal talons and bears it away to a favourite perch, there to enjoy it at leisure. This is the hawk that is so glad to find a deserted woodpecker's hole for its nest. How many other birds gratefully accept those skilful carpenters' vacant tenements!

AMERICAN OSPREY

Called also: Fish Hawk A pair of these beautiful big hawks, that had nested year after year in the top of a tall pine tree on the Manasquan River, New Jersey, were great pets in that region. An old fisherman of Barnegat Bay told me that when he was hauling in his seine one day, he saw the male osprey strike the water with a splash, struggle an instant with a great fish that had been following his net, and disappear below the waves, never to rise again. The bird more than met his match that time. The fish was far larger than he expected, so powerful that it easily dragged him under, once his talons were imbedded in the fish's flesh. For the rest of the summer the widowed osprey always stayed about when the fisherman hauled his net on the beach, and bore away to her nest the worthless fish he left in it for her special benefit. But after rearing her family-a prolonged process for all the hawks, eagles, and owls-she never returned to the neighbourhood. Perhaps old associations were too painful; perhaps she was shot on her way South that winter; or perhaps she took another mate with more sense and less greed, who preferred to reside elsewhere. As you may imagine, fish hawks always live near water. In summer they frequent the inlets along the Atlantic coast, but over inland lakes and rivers also, many fly back and forth. You may know by their larger size-they are almost two feet long-and by their slow flight that they are not the winter gulls. Their dusky backs and white under parts harmonise well with the marine picture, North, or South. Their plumage contains more white than that of any other hawk. No matter how foggy the day or how quietly the diving osprey may splash to catch his fish dinner, any bald-headed eagle in the vicinity is sure to detect him in the act of seizing it, and then to relieve him of it instantly.

OWLS

Like many children I know, owls begin to be especially lively toward night, only they make no noise as they fly about. Very soft, fluffy plumage muffles their flight so that they can drop upon a meadow mouse creeping through the grass in the stilly night before this wee, timorous beastie suspects there is a foe abroad. As owls live upon mice, mostly, it is important they should be helped to catch them with some device that beats our traps. If mice should change their nocturnal habits, the owl's whole scheme of existence would be upset, and the hawks would get the quarry that they now enjoy: mice, rats, moles, bats, frogs and the larger insects. You see the farmer has invaluable day and night allies in these birds of prey which take turns in protecting his fields from rodents, one patrol working while the other sleeps. On the whole, owls are the more valuable to him. They usually continue their good work all through the winter after the hawks have gone South. Can you think of any other birds that work for him at night? Not only can owls fluff out their loose, mottled plumage, but they can draw it in so close as to change their shape and size in an instant, so that they look like quite different birds, or rather not like birds at all, but stumps of trees. Altering their outlines, changing their shape and size at will, is one of these queer birds' peculiarities. Their eyes, set in the centre of feathered discs, do not revolve in their sockets, but are so fixed that they look only straight ahead, which is why an owl must turn his head every time he wishes to glance to the right or left. Another peculiarity is the owls' method of eating. Bolting entire all the food they catch, head first, they digest only the nutritious portions of it. Then, bowing their heads and shaking them very hard, they eject the bones, claws, skin, hair and fur in matted pellets, without the least distress. Some children I know, who swallow their food in a hurry-cherry stones, grape skins, apple cores and all-need a similar, merciful digestive apparatus.

Turkey buzzard: one of Nature's house cleaners  The beautiful little sparrow hawk

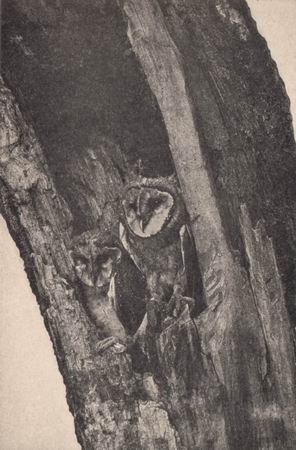

Barn Owl Like the hawks, owls are devoted, life-long mates. The females are larger than the males. Some like to live in dense evergreens that hide them from teasing blue jays and other foes by day; some, like the barn owl, prefer towers, church steeples or the tops of barns and other buildings; some hide in hollow trees or deserted woodpeckers' holes, but all naturally prefer to take their long, daily naps where the sunlight does not penetrate. They live in their homes more hours than woodpeckers or any other birds. No doubt we pass by many sleeping owls without suspecting their presence.

BARN OWL

Called also: Monkey-faced Owl This is the shy, odd-looking, gray and white mottled owl with the triangular face and slim body, about a foot and a half long, that comes out of its hole at evening with a wild scream, startling timid and superstitious people into the belief that it is uncanny. The American counterpart of "wise Minerva's only fowl," its large eye-discs and solemn blink certainly make it look like a fit companion for the goddess of wisdom. A tame barn owl, owned by a gentleman in Philadelphia, would sit on his shoulder for hours at a time. It felt offended if its master would not play with it. The only way the man could gain time for himself during the bird's waking hours, was to feed it well and leave a stuffed bird for it to play with when he went out of the room, just as Jimmy Brown left a doll with his baby sister when he went out to play; only the man could not tack the owl's petticoats to the floor. A pair of barn owls lived for many years in the tower of the Smithsonian Institution, Washington. Dr. Fisher found the skulls of four hundred and fifty-four small mammals in the pellets cast about their home. Another pair lived in a tower and on the best of terms with some tame pigeons. Happily the owls had no taste for squab, but the debris of several thousand mice and rats about their curious dwelling proved that their appetite needed no , coaxing with such a delicacy.

SHORT-EARED OWL

Called also: Marsh Owl; Meadow Owl This owl, and its long-eared cousin, wear the tufts of feathers in their ears that resemble harmless horns. Unlike its relatives, the short-eared owl does some hunting by daylight, especially in cloudy weather, and like the marsh hawk it prefers to live in grassy, marshy places frequented by meadow mice. On the other hand, the long-eared owl respects family traditions, and goes about only after dark. "It usually spends the day in some evergreen woods, thick willow copse or alder swamp, although rarely it may be found in open places," says Dr. Fisher. "The bird is not wild and will allow itself to be closely approached. When conscious that its presence is recognised, it sits upright, draws the feathers close to its body, and erects the ear-tufts, resembling in appearance a piece of weather-beaten bark more than a bird." The long and the short of it is, that few people, except professional bird students, know very much about these or any other owls, for few find them by day or forsake their couches when they are abroad. We may take Dr. Johnson's advice and "give our days and nights to the study of Addison," but few of us give even a part of our days and less of our nights to the study of the birds about us.

BARRED OWL

Called also: Hoot Owl If "a good child should be seen and not heard" what can be said for this owl? Its deep-toned whoo-whoo-who-whoo-to-whoo-ah, like the wail of some lost soul asking the way, is the only indication you are likely to have that a hoot owl lives in your neighbourhood. You can imitate its voice and deliberately "hoot it up." Few people who know its voice will ever see its smooth, round, bland, almost human face. "As useless as a last year's nest" can have no meaning to a pair of these large hardy owls that go about toward the end of winter looking for a deserted woodpecker's nest or a hawk's, crow's, or squirrel's bulky cradle in some tree top. Ever after they hold it as their own. Farmers shoot the owl that occasionally takes one of their broilers or a game bird, not knowing that the remainder of its diet really leaves them in its debt.

SCREECH OWLS

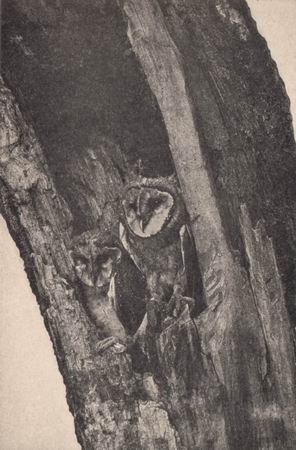

A boy I know had a pair of little screech owls invite themselves to live in a box he had nailed up for bluebirds in his father's orchard. Although they had full liberty, in time they became tame pets, even pampered darlings, with a willing slave to trap mice for them in the corn crib and hay loft. At first mice were plentiful enough, and every day after school the boy would empty the traps, climb the apple tree and feed the owls. But presently the mice learned the danger that may lurk behind an innocent looking lump of cheese. One foolish, hungry mouse now and then was all the boy could catch. This he would carry by the tail to his sleeping pets, arouse them by dangling it against their heads, at which, while half asleep, they would click their beaks like castanets. When both were wide awake he would allow one of them to bolt the mouse while he still held on firmly to the tail. Then, jerking the mouse back out of the owl's throat, he would allow the other owl to really swallow it. When next he caught a mouse, the operation was reversed: the owl that had been satisfied before now gulped the mouse first, only to have it jerked away and fed to its mate. In this way, strange to say, the boy kept on friendly terms with the pair for several weeks, when he discovered that they liked bits of raw beef quite as well as mice. After that he carried his queer pets to the house and kept them in his room all winter. Early in the spring they returned to the bird house and raised a family of funny, fluffy, plump little owlets. This boy discovered for himself the screech owls' strange characteristic of changing their colour without changing their feathers, as moulting song birds change theirs. They have a rusty, reddish-brown phase and a mottled-gray phase. So far as is known, these changes of colour are not dependent upon age, sex, or season. No one understands what causes them or what they mean. Sometimes the same family will contain birds with plumage that is rusty-brown or gray or intermediate. But you may always know a screech owl by its small size (it is only about as long as a robin) and by the ear tufts that make it look wide-awake and very wise. By day it keeps well hidden in some deserted woodpecker's hole or a hollow in some old orchard tree, which is its favourite residence; but some mischievous little birds, with sharper eyes than ours, often discover its hiding place, wake it up, and chase it, blinking and bewildered, all about the farm. By night, when its tormentors are asleep, this little owl goes forth for its supper, and then we hear its weird, sweet, shivering, tremulous cry. Because it lives near our homes and is, perhaps, the commonest of the owls all over our country, every child can know it by sound, if not by sight.  Father and mother barn owls

The heavenly twins: young barn owl |