|

1999-2004 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click Here to return to Birds Every Child Should Know Content Page Click Here to return to last Chapter |

(HOME) |

|

1999-2004 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click Here to return to Birds Every Child Should Know Content Page Click Here to return to last Chapter |

(HOME) |

|

CHAPTER XI

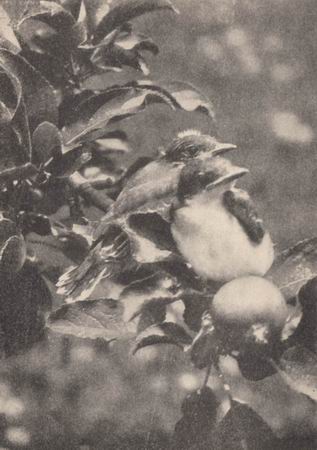

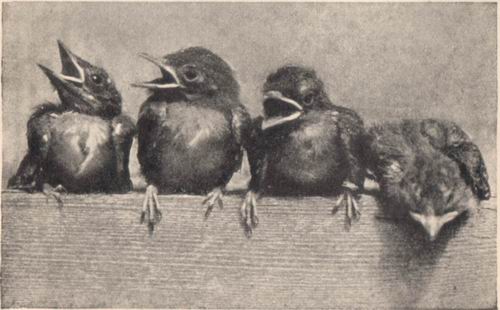

THE FLYCATCHERS KINGBIRD CRESTED FLYCATCHER PHOEBE PEWEE LEAST FLYCATCHER THE FLYCATCHERS WHEN you see a dusky bird, smaller than a robin, lighter gray underneath than on its sooty-brown back, with a well-rounded, erect head, set on a short, thick neck, you may safely guess it is one of the flycatchers-another strictly American family. If the bird has a white band across the end of its tail it is probably the fearless kingbird. If the feathers on top of its head look as if they had been brushed the wrong way into a pointed crest; moreover, if some chestnut colour shows in its tail when spread, and its pearly gray breast shades into yellow underneath, you are looking at the noisy "wild Irishman" of birddom, the crested flycatcher. Confiding Phoebe wears the plainest of dull clothes with a still darker, dusky crown cap, and a line of white on her outer tail feathers. She and the plaintive wood pewee, who has two indistinct whitish bars across her extra-long wings, are scarcely larger than an English sparrow; while the least flycatcher, who calls himself Chebec, is, as you may suppose, the smallest member of the tribe to leave the tropics and spend the summer with us. Male and female members of this family wear similar clothes, fortunately for " every child" who tries to identify them. You can tell a flycatcher at sight by the way he collects his dinner. Perhaps he will be sitting quietly on the limb of a tree or on a fence as if dreaming, when suddenly off he dashes into the air, clicks his broad bill sharply over a winged insect, flutters an instant, then wheels about and returns to his favourite perch to wait for the next course to fly by. He may describe fifty such loops in mid-air and make as many fatal snap-shots before his hunger is satisfied. A swallow or a swift would keep constantly on the wing; a vireo would hunt leisurely among the foliage; a warbler would restlessly flit about the tree hunting for its dinner among the leaves; but the dignified, dexterous flycatcher, like a hawk, waits patiently on his lookout for a dinner to fly toward him. "All things come to him who waits," he firmly believes. None of the family is musically gifted, but all make a more or less pleasing noise. Flycatchers are solitary, sedentary birds, never being found in flocks; but when mated, they are devoted home lovers. We are apt to think of tropical birds as very gaily feathered, but certainly many that come from warmer climes to spend the summer with us are less conspicuous than Quakers.  The dashing, great crested flycatcher  Baby kingbirds in an apple tree KINGBIRD Called also: Bee Martin In spite of his scientific name, which has branded him the tyrant of tyrants, the kingbird is by no means a bully. See him high in air in hot pursuit of that big, black, villainous crow, who dared try to rob his nest, darting about the rascal's head and pecking at his eyes until he is glad to leave the neighbourhood ! There seems to be an eternal feud between them. Even the marauding hawk, that strikes terror to every other feathered breast, will be driven off by the plucky little kingbird. But surely a courageous home defender is no tyrant. A kingbird doesn't like the scolding catbird for a neighbour, or the teasing blue jay, or the meddlesome English sparrow, but he simply gives them a wide berth. He is no Don Quixote ready to fight from mere bravado. Tyrannus tyrannus is a libel. For years he has been called the bee martin and some scientific men in Washington determined to learn if that name, also, is deserved. So they collected over two hundred kingbirds from different parts of the country, examined their stomachs and found bees -- mostly drones -- in only fourteen. The bird is too keen sighted and clever to snap up knowingly a bee with a sting attached, you may be sure; but occasionally he makes a mistake when, don't you believe, he is more sorry for it than the beekeeper? He destroys so many robber flies-a pest of the hives-that the intelligent apiarist, who keeps bees in his orchard to fertilise the blossoms, always likes to see a pair of kingbirds nesting in one of his fruit trees. The gardener welcomes the bird that eats rose chafers; the farmer approves of him because he catches the gadfly, that torments his horses and cattle, as well as the grasshoppers, katydids and crickets that would destroy his field crops if left unchecked. From a favourite lookout on a tall mullein stalk, a kingbird neighbour of mine would detect an insect over one hundred and seventy feet away, where no human eye could see it, dash off, snap it safely within his bill, flutter uncertainly an instant, then return to his perch ready to "loop the loop" again any moment. The curved clasp at the tip of his bill and the stiff hairs at the base helped hold every insect his prisoner. While waiting for food to fly into sight the watcher did a good deal of calling. His harsh, chattering note, ching, ching, which penetrated to a surprising distance, did not express alarm, but rather the exultant joy of victory.  Four crested flycatchers who need to have their hair brushed  Time for these young phoebes to leave the nest  Young phoebes on a bridge trestle He and his mate were certainly frantic with fear, however, when I climbed into their apple tree one June morning, determined to have a peep at the five creamy-white eggs, speckled with brown and pale lilac, that had just been laid in the nest in a crotch near the end of a stout limb. Whirling and dashing about my head, the pair made me lose my balance, and I tumbled ten feet or more to the ground. As the intruder fell, they might well have exclaimed -- perhaps they did -- "Sic semper tyrannis!"

CRESTED FLYCATCHER

Far more tyrannical than the kingbird is this "wild Irishman," as John Burroughs calls the large flycatcher with the tousled head and harsh, uncanny voice, who prowls around the woods and orchards startling most feathered friends and foes with a loud, piercing exclamation that sounds like What! Unlike good children, he is more often heard than seen. That the solitary, unpopular bird takes a mischievous delight in scaring its enemies, you may know when I tell you that it likes better than any other lining for its nest, a cast snake skin. Is it any wonder that the baby flycatchers' hair stands on end? If the great-crest cannot find the skin of a snake to coil around her eggs, or to hang out of the nest, she may use onion skins, or oiled paper, or even fish scales; for what was once a protective custom, sometimes becomes degraded into a cheap imitation of the imitation in the furnishing of her house. Into an abandoned woodpeckers' hole or a bluebirds' cavity after the babies of these early nesters have flown, or into some unappropriated hollow in a tree, this flycatcher carries enough grasses, weeds and feathers to keep her nestlings cozy during those rare days of June beloved by Lowell, but which Dr. Holmes observed are often so rare they are raw.

PHOEBE

Called also: Bridge Pewee; Dusky Flycatcher; Water Pewee The first of its family to come North, as well as the last to leave us for the winter, the phoebe appears toward the end of March to snap up the first insects warmed into life by the spring sunshine. Grackles in the evergreens, redwings in the swampy meadows, bluebirds in the orchard may assure us that summer is on the way; but the homely, confiding phoebe, who comes close about our houses and barns, brings the good news home to us every hour. Pewit-phoebe, pewit-phoebe, he calls continually. As he perches on the peak of a building or other point of vantage, notice how vigorously he wags his tail when he calls, and turns his head this way and that, to keep an eye in all directions lest a bite should fly by him unawares. Presently a mate comes from somewhere south of the Carolinas where she has passed the winter; for phoebes are more hardy than the rest of the family and do not travel all the way to the tropics. With unfailing accuracy she finds the region where she built her nest the previous season or where she herself was hatched. This instinct of returned direction is marvellous, is it not? Sometimes it is hard enough for us humans to find the way home when not ten miles away. Did you ever get lost? Birds almost never do. Phoebes like a covering over their heads to protect their nests from spring rains, so you will see a domesticated couple going about the place like a pair of wrens, investigating niches under the piazza roof, beams in an empty barn loft and projections under bridges and trestles. By the middle of April a neat nest of moss and lichen, plastered together with mud and lined with long hair or wool, if sheep are near, is made in the vicinity of their home of the year before. The nursery is exquisitely fashioned -- one of the best pieces of bird architecture you are likely to find. Some over-thrifty housekeepers, nevertheless, tear down nests from their piazzas, because the poor little phoebes are so afflicted with lice that they are considered objectionable neighbours. Many wild birds, like chickens, have their life-blood drawn by these minute pests. But a thorough dusting of the phoebe's nest with Persian powder would bring relief to the tormented birds, save their babies, perhaps, from death and keep the piazza free from vermin. No birds enjoy a bath in your fountain or water pan more than these tormented ones. From purely selfish motives it pays to cultivate neighbours ever on the lookout for flies, wasps, May beetles, click beetles, elm destroyers and the moth of the cutworm. The first nest is usually so infested that the phoebes either tear it down in July, and build a new one on its site, or else make the second nest at a little distance from the first. The parents of two broods of from four to six ravenously hungry, insectivorous young, with an instinctive desire to return to their old home year after year, should surely meet no discouragement from thinking farmers' wives. Shouldn't you think that baby phoebes, reared in nests under railroad bridges, would be fearfully frightened whenever a train thundered overhead?

WOOD PEWEE

When you have been wandering through the summer woods did you ever, like Trowbridge, sit down

Doubtless this demure, gentle little cousin of the noisy, aggressive, crested flycatcher has no secret sorrow preying at its heart, but the tender pathos of its long-drawn notes would seem to indicate that it is rather melancholy. And it sings (in spite of the books which teach us that the flycatchers are "songless, perching birds") from the time of its arrival from Central America in May until only the tireless indigo bunting and the red-eyed vireo are left in the choir in August. But how suddenly its melancholy languor departs the instant an insect flies within sight! With a cheerful, sudden sally in mid-air, it snaps up the luscious bite, for it can be quite as active as any of the family. While not so ready to be neighbourly as the phoebe, the pewee condescends to visit our orchards and shade trees. When nesting time comes, it looks for a partly decayed, lichen-covered branch, and on to this saddles a compact, exquisite cradle of fine grass, moss and shreds of bark, binding bits of lichen with spiders' web to the outside until the sharpest of eyes are needed to tell the stuccoed nest from the limb it rests on. Only the tiny hummingbird, who also uses lichen as a protective and decorative device, conceals her nest so successfully.

LEAST FLYCATCHER

Called also: Chebec It is not until he calls out his name, Chebec! Chebec! in clear and business-like tones from some tree-top that you could identify this fluffy flycatcher, scarcely more than five inches long, whose dusky coat and light vest offer no helpful markings. Not a single gay feather relieves his sombre suit. Isn't this a queer, Quakerly taste for a bird that spends half his life in the tropics among gorgeously feathered friends? Even the plain vireos, as a family, wear finer clothes than the dusky flycatchers. You may know that the chebec is not one of those deliberate searchers of foliage by his sudden, murderous sallies in mid-air. Abundant from Pennsylvania to Quebec, the least flycatchers are too inconspicuous to be much noticed. They haunt apple orchards chiefly at nesting time, fortunately for the crop, and at no season secrete themselves in shady woods as pewees do. A little chebec neighbour of mine used to dart through the spray from the hose that played on the lawn late every afternoon during a drought, and sit on the tennis net to preen his wet feathers; but he nearly put out my eyes in his excitement and anger when I presumed on so much friendliness to peep into his nest. |