| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2011 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

| CHAPTER XIV.

TROUBLES OF THE POLAR EXPLORER. It is doubtful whether Dr. Cook will ever be able to paint in vivid enough colors the privations he endured in his rush toward the north. To him, probably, much of what he endured will appear as a nightmare. He will start from his pillow, some nights, fancying himself still driving a dog sled through blinding snows. Even if his memory retains distinctly what he suffered, he will doubtless find it hard to pick out words to convey the idea to others. To understand it at all, one may go back to the records that are left to the deeds of Cook's predecessors in polar search. No more thrilling suggestion could be found of the experiences men are willing to suffer in the pursuit of knowledge for the sake of outstripping others. The early arctic explorers, of course, endured much that Cook was saved through his being able to profit by experience, and through his taking advantage of modern methods. Scurvy, for example, the disease that has brought a horrible end to so many who lived for months in bitter cold, did not threaten him. He knew how to guard against it, and he had foods that did not contain the seeds of that malady. But the death he faced was the same that carried away some eight hundred men who sought the pole at one time or another — the death, slow, torturing, and malignant, caused by intense cold. Farther on in this volume will be found an account of some of the early arctic voyages that ended in tragedy. Here, however, an effort will be made to give some idea of the sight and sounds peculiar to the polar region. At the north pole itself the sun rises and sets only once in twelve months. From March 21 to September 23 daylight continues; from September 23 to March 21 the sun is never visible. Dr. Cook arrived at the pole during the period of daylight; yet it must have been a cheerless daylight he saw. For what is daylight unless it reveals life and beauty? At the pole, so Dr. Cook himself says, there was no sign of animation at all — either of man or beast. It was, he says, "an endless field of purple snows. No life. No land. No sight to relieve the monotony of frost. We (he and his two Eskimo companions) were the only pulsating creatures in a dead world of ice." The heat at midsummer in the polar region is hardly ever above the freezing point; at midwinter, the cold is so intense that one's eyes would freeze in their sockets if exposed to it. And there are other strange and terrifying features. As summer gives place to the cold of autumn, and as winter gives way to the mild temperature of spring, there comes down upon the water a dense mass or fog, to which the name of "frost-smoke" is given. An ancient Greek mariner, Pytheas, who sailed far north, was led by this "frost smoke" to give a curious account of his trip. He was there during the six months' darkness, and he says he came to a great dark. wall rising up out of the sea. He could not see beyond it. At the same time, according to his story, something seized his ship and held it motionless on the water, so the winds could not move it. He supposed he had come to a place where a parapet ran around the world to keep men from falling over (for in the time of this explorer, of course, men believed the world was flat). So this voyager hurried home and told his friends he had reached the limits of the earth. Later navigators saw sights some of which are to be experienced today. Many of these mariners got far enough north to see the great icebergs, floating majestically in the sea and towering like mountains. Some saw the animals that dwell in the far north — the polar bear with its coat of shaggy white, fur; the walrus, with its gleaming tusks hanging down from its upper jaws; the ungainly seals; the penguins, strange birds with short stumps of wings and uncouth cries; and whales, spouting and floundering in the sea. The sounds are sometimes as terrifying as the sights. The frosty air carries noises a long distance. When Commander Peary was on a far northern island he says he heard the voices of men talking a mile away. "In the depth of winter," says a writer, "when the cold has its icy grip on everything, the silence is unbroken along the shores of the Polar Sea; but when the frost sets in, and again when the winter gives way to spring, there is abundance of noise. As the frost comes down along the coast, rocks are split asunder with a noise of big guns, and the sound goes booming away across the frozen tracts, startling the slouching bear in his lonely haunts, and causing him to give vent to his hoarse, barking roar in answer. The ice, just forming into sheets, creaks and cracks as the rising or falling tide strains it along the shore; fragments falling loose upon its skid across the surface with the ringing sound which travels so far. In the spring the melting ice-floes groan as they break asunder; with a mighty crash the unbalanced bergs fall over, churning the water into foam with their plunge, and bears and foxes and all the other arctic animals call and bark to one another as they awaken from their winter sleep." A source of trouble to arctic travelers often are the characteristics of the Eskimo dogs. These animals are the only ones that can be depended on to draw the sledges, for no others could endure the cold and the lack of food that accompanies travel in regions of solid ice. But no traveler, unless he be as experienced as Dr. Cook, who used them exclusively after leaving his ship, can manage the queer creatures. Some of their traits are interestingly described by a writer on polar exploration, as follows: "When a dog team is harnessed up to a sledge, every dog does not pull his hardest, and a suggestion from the whip is advisable. The dog, however, is inclined to resent it, and at once bites his neighbor by way of protest. The neighbor in turn bites his neighbor, who does the same, until the whole team has received the sting arising from the first lash, and all the dogs are howling and snapping and jumping over one another. The application of the whip handle instead of the whip lash is then necessary, and when at length quiet is restored, the driver has to set to work to unplait the harness, which has been twisted and tied into a terrible tangle by the antics of the team. When, at the expense of a great deal of patience and time, everything is ready for a fresh start, the inexperienced driver is able to estimate the value of cracking the whip over, instead of on, the back of a lazy dog. "Even then, however, it is not all plain sailing. The dogs possess a wisdom of their own, and they never act so well together as when they reach a piece of particularly rough ice over which the sledge does not move easily. Directly they find that they have to lean heavily against the collar to pull the load forward, they with one accord turn around, sit down, and look at the driver. If he is inexperienced, he lashes about him with his whip, and the dogs fight and tangle the harness; if he knows his animals, he puts his shoulder to the sledge, pushes it forward on to the toes of the team, whereupon each one gets up, hurries out of the way of the threatening sledge runners, and together pull it. easily over the rough place. "Another peculiarity of the dogs is their extraordinary appetite for leather. Shark skin the Eskimo consider to be bad for them because of its excessive roughness, but birds' skin, with the feathers on, are greatly relished by the insatiable feeders, and, as has been said, leather is an especial luxury. The dogs are incorrigible thieves, and frequently sneak into the tents or, if on board ship, into cabins, in search of plunder. They are generally greeted with a kick, but should it be sufficiently energetic to dislodge the kicker's shoe, the dog at once seizes the delicacy and makes for a quiet spot on the ice where he can devour it at his leisure." Desperate courage and the skill of a big-game hunter are required if one journeys in the arctic. When the rations run out, as they did in Dr. Cook's case before his return journey was over, the traveler has to depend on his ability to bring down the animals of the region. Some of the experiences of an exploring party under these conditions are thus described: "A small opening in the ice pack was discovered a mile or so from the camp, and on the ice around the water three seals were resting, having evidently been caught in the ice when it closed. With great care the hunters crept over the ice toward the animals, whose sacrifice meant so much to the castaways. Only two had rifles, the others carrying harpoons they had made from the tent poles, and which were anything but reliable weapons. Steady aim was taken by the two men who had the rifles at the two larger of the seals. Firing together one seal fell dead; the one which was not aimed at plunged into the water, and the other, badly wounded, hobbled to the edge of the ice. In another moment he would have been over and probably sunk to the bottom, had not one of the men flung away his harpoon and, springing forward, managed to seize the hind flippers of the wounded creature. His comrades rushed to his assistance and dragged both him and the seal back from the opening onto the ice, where the latter was quickly despatched. "They were harnessing themselves to their victims in order to drag them over to the camp, when a loud snort from the opening caused them to start around just in time to see the third seal disappearing under the water. At once they understood the situation. The opening was the only one for miles, and the seal was compelled to come to the surface there to breathe, as he could not reach the top anywhere else for the ice. It was at once decided to wait for him, but as, if he were shot while in the water, he would inevitably sink to the bottom and be lost to them, they determined to lay a trap for him. "The seals already killed were placed in natural attitudes near the water, and the men hastily retired to sheltering hammocks, to wait the return. The men with the rifles were both to fire upon him as soon as he emerged onto the ice, for he was too valuable to be lost. They had not waited very long before he reappeared and, raising his head high out of the water looked around. Seeing nothing but the two seals on the ice, he swam leisurely round and round the opening before scrambling up onto the ice. As he reached it and moved towards his two companions, the men, who had been carefully aiming at him, fired and killed him. "With the three seals, the party returned to the camp in high spirits, their arrival being the signal for general rejoicing, for not only would the blubber of the seals keep the lamp supplied with oil, but their skins were very welcome additions to the stock of warm coverings and the meat was an invaluable addition to the larder. "Really it was more, but of that they were not aware until two days later, when one of the men was awakened by a short barking roar of a bear. He quickly roused his companions, and they made their way out of the hut with what weapons they possessed. "The flesh of the seals had been suspended on a line between two poles near the other provisions so as to protect it from any chance visit by wolves or bears. As the first man peered out from the hut opening, he saw in the dim twilight two bears standing underneath the line of meat, sniffing up at it and growling. They had, it was afterwards learned, picked up the trail where the dead seals had been dragged from the opening in the ice, and had followed it to the camp. "The man whispered back to his companions what he saw, and another man, armed with a rifle, crept to his side. Aiming together behind the shoulder of the larger of the bears, they fired simultaneously and brought their quarry down. Immediately the other bear turned towards the opening and with snarling teeth advanced. A third rifle was fired point-blank at its head, but the bullet failed to penetrate the massive skull, though it made the beast change its direction. As it turned away the men realized what it meant if it escaped, and there was a rush after it, the men loading and firing as quickly as they could load, so as to secure it before it disappeared in the dim grey twilight. It fell wounded, and was despatched by means of the impromptu spears." Major-General A. W. Greeley, himself a polar hero, has this to say, in his "Handbook of Polar Discoveries," of the hardships encountered in the ice fastnesses: "If one would gain an adequate idea of the true aspects of such voyaging he must turn to the original journals, penned in the great White North by brave men whose 'purpose held to sail beyond the sunset.' In those volumes will be found tales of ships beset not only months, but years, of ice packs and ice fields of extent, thickness and mass so enormous that description conveys no idea; of boat journeys where constant watchfulness alone prevented instant death by drifting bergs or commingling ice floes; of land marshes when exhausted humanity staggered along, leaving traces of blood on snow or rock; of sledge journeys over chaotic masses of ice, when humble heroes straining at the drag ropes struggled on because the failure of one compromised the safety of all; of solitude and monotony, terrible in the weeks of constant polar sunlight, but unsettling the reason in the months of continuous Arctic darkness; of silence awful at all times, but made yet more startling by astounding phenomena that appeal noiselessly to the eye; of darkness so continuous and intense that the disturbed mind is driven to wonder whether the ordinary course of nature will bring back the sun or whether the world has been cast out of its orbit in the planetary universe into new conditions; of cold so intense that any exposure is followed by instant freezing; of monotonous surroundings that threaten with time to unbalance the reason; of deprivations wasting the body and so impairing the mind; of failure in all things, not only of food, fuel and clothing and shelter — for Arctic service foreshadows such contingencies — but the bitter failure of plans and aspirations, which brings almost inevitably despair in its train. "Failure of all things, did I say? Nay, failure, be it admitted, of all the physical accessories of conceived and accomplished action, but not failure in the higher and more essential attributes — not of the mental and moral qualities that are the foundation of fortitude, fidelity and honor. Failure in this latter respect have been so rare in Arctic service as to justly make each offender a byword and scorn to his fellow laborers and successors. Patience, courage, fortitude, foresight, self-reliance, helpfulness — these grand characteristics of developed humanity everywhere, but which we are inclined to claim as especial endowments of the Teutonic races, find ample expression in the detailed history of Arctic exploration. If one seeks to learn to what extent man's determination. and effort dominate even the most adverse environment, the simple narratives of Arctic exploration will not fail to furnish striking examples." Many interesting accounts are given of the terrible cold, which, after all, is the worst of the polar explorers' troubles. Capt. John Franklin — afterwards admiral — speaks of fish being frozen, saying: "It may be worthy of notice here, that the fish froze as they were taken out of the nets, and in a short time became a solid mass of ice, and by a blow or two of the hatchet were easily split open, when the intestines might be removed in one lump. If, in this completely frozen state, they were thawed before the fire, they recovered their animation. This was particularly the case with the carp; and we had occasion to observe it repeatedly, as Dr. Richardson (one of the party) occupied himself in examining the structure of the different species of fish, and was always, in the winter, under the necessity of thawing them before he could cut them. We have seen a carp recover so far as to leap about with much vigor after it had been frozen for thirty-six hours." If such is the effects on fish, what of men? This same Dr. Richardson nearly lost his life while the expedition of which he and Franklin were members in 1821 was exploring the north coast of America. They traveled for a time in canoes, and their food gave out. Daily they became weaker, and less capable of exertion; one of the canoes was so much broken by a fall, that it was burned to cook a supper; the resource of fishing, too, was denied them, for some of the men, in the recklessness of misery, threw away the nets. Rivers were to be crossed by wading, or in the canoe; on one of these occasions Franklin took his seat with two of the voyageurs in their frail bark, when they were driven by the force of the stream and the wind to the verge of a frightful rapid, in which the canoe upset, and, but for a rock on which they found footing, they would there have perished. On June 19th, previous to setting out, the whole party ate the remains of their old shoes, and whatever scraps of leather they had, to strengthen their stomachs for the fatigue of the day's journey. "These," adds Franklin, "would have satisfied us in ordinary times, but we were now almost exhausted by slender fare and travel, and our appetites had become ravenous. We looked, however, with humble confidence to the great Author and Giver of all good for a continuance of the support which had hitherto been always supplied to us at our greatest need." Dr. Richardson finally undertook to swim the Copperwire river, carrying a line by which a raft might be hauled over. "He launched into the stream," says Franklin, "with the line round his middle, but when he had got to a short distance from the opposite bank, his arms became benumbed with cold, and he lost the power of moving them; still he persevered, and, turning on his back, had nearly gained the opposite shore, when his legs also became powerless, and, to our infinite alarm, we beheld him sink. We instantly hauled upon the line, and he came again on the surface, and was gradually drawn ashore in an almost lifeless state. Being rolled up in blankets, he was placed before a good fire of willows, and, fortunately, was just able to speak sufficiently to give some slight directions respecting the manner of treating him. He recovered strength gradually, and, through the blessing of God, was enabled, in the course of a few hours, to converse, and by the evening was sufficiently recovered to remove into the tent. We then regretted to learn that the skin of his whole left side was deprived of feeling, in consequence of exposure to too great heat. He did not perfectly recover the sensation of that side until the following summer. I cannot describe what every one felt at beholding the skeleton which the doctor's debilitated frame exhibited. When he stripped, the Canadians simultaneously exclaimed, 'Ah! que nous sommes maigres!' " After reading that, could one imagine a mosquito in the Arctic? Yet they are a terrible pest there. Captain Hall describes a walk in July, in the following language: "The sun was about five degrees high. Not a breath of air stirring, the sun shining hot, and the mosquitoes desperately intent on getting all the blood of the only white man of the country. I kept up a constant battling with my seal-skin mittens directly before my face, now and then letting them slap first on one and then on the other of my hands, which operations crushed many a foe. It seemed to me at times as if I never would get back. Minutes were like hours, and the distance of about two miles seemed more like half a score. At length I got back to my home, both temperature and temper high. I made quick work in throwing open the canvas roof of our stores, and, getting to our medicine-chest, snatched a half-pint bottle of mosquito-proof oil, and with a little of this besmeared every exposable part of my person. How glorious and sudden was the change! A thousand devils, each armed with lancet and blood-pump, courageously battling my very face, departed at once in supreme disgust at the confounded stink the coal-oil had diffused about me." Of the dreadful thirst of the Arctic, which some seek to allay by eating snow, the diary of an explorer of the last century says: "The use of snow when persons are thirsty does not by any means allay the insatiable desire for water; on the contrary, it appears to be increased in proportion to the quantity used, and the frequency with which it is put into the mouth. For example: a person walking along feels intensely thirsty, and he looks to his feet with coveting eyes; but his sense and firm resolutions are not to be overcome so easily, and he withdraws the open hand that was to grasp the delicious morsel and convey it into his parching mouth. He has several miles of a journey to accomplish, and his thirst is every moment increasing; he is perspiring profusely, and feels quite hot and oppressed. At length his good resolutions stagger, and he partakes of the smallest particle, which produces a most exhilarating effect; in less than ten minutes he tastes again and again, always increasing the quantity; and in half an hour he has a gum-stick of condensed snow, which he masticates with avidity, and replaces with assiduity the moment that it has melted away. But his thirst is not allayed in the slightest degree; he is as hot as ever, and still perspires; his mouth is in flames, and he is driven to the necessity of quenching them with snow, which adds fuel to the fire. The melting snow ceases to please the palate, and it feels like red-hot coals, which, like a fire-eater, he shifts about with his tongue, and swallows without the addition of saliva. He is in despair; but habit has taken the place of his reasoning faculties, and he moves on with languid steps, lamenting the severe fate which forces him to persist in a practice which in an unguarded moment he allowed to begin. . . . I believe the true cause of such intense thirst is the extreme dryness of the air when the temperature is low." The woes of the explorer cannot better be told than by extracts from the diary of John Herron, one of a party left adrift on an ice-raft during the expedition of the ship Polaris, under Charles F. Hall, in 1872. There were nineteen persons in his party, including two women and four children. Describing the way the party was lost, Herron says: "October 15. — Gale from the southwest; ship made fast to floe; bergs pressed in and nipped the ship until we thought she was going down; threw provisions overboard, and nineteen souls got on the floe to receive them and haul them up on the ice. A large berg came sailing down, struck the floe, shivered it to pieces, and freed the ship. She was out of sight in five minutes. We were afloat on different pieces of ice. We had two boats. Our men were picked up, myself among them, and landed on the main floe, which we found to be cracked in many places. Saved very little provisions. "October

16. — We remained shivering all night. Morning fine; light breeze

from the north; dose to the east shore. The berg that did so much

damage half a mile to the northeast of us. Captain Tyson reports a

small island a little to the north of the berg and close to the land.

Plenty of open water. We lost no time in launching the boats, getting

the provisions in and pulling around the berg, when we saw the

Polaris. She had steam up, and succeeded in getting a harbor. She got

under the lee of an island and came down with her sails set — jib,

foresail, mainsail and staysail. She must have seen us, as the island

was four or five miles off. We expected her to save us, as there was

plenty of open water, beset with ice, which I think she could have

gotten through. In the evening we started with the boats for shore.

Had we reached it, we could have walked on board in one hour, but the

ice set in so fast when near the shore that we could not pull through

it. We had a narrow escape in jumping from piece to piece, with the

painter in hand, until we reached the floe. We dragged the boat two

or three hundred yards, to a high place, where we thought she would

be secure until morning, and made for our provisions, which were on a

distant part of the floe. We were too much worn out with hunger and

fatigue to bring her along to-night, and it is nearly dark. We cannot

see our other boat or our provisions; the snow-drift has covered our

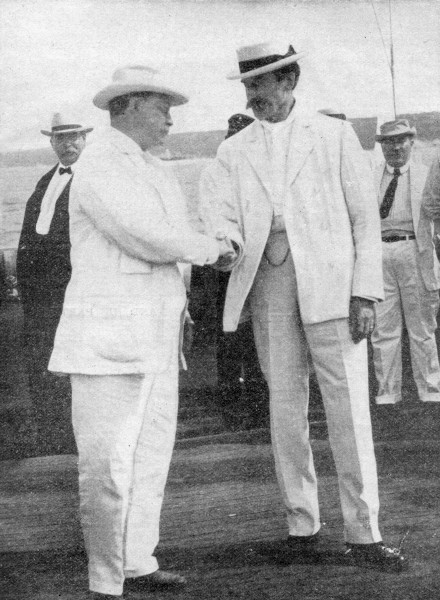

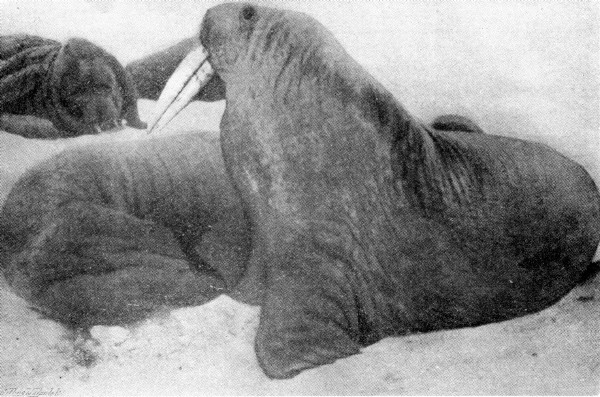

late tracks."  ROOSEVELT BIDDING PEARY GOOD-BYE JUST BEFORE THE START FOR THE POLE.  THE WALRUS — THESE ANIMALS KEPT DR. COOK AND HIS PARTY ALIVE ON THEIR RETURN JOURNEY.  DR. COOK IN THE ICE NORTH OF THE 37TH PARALLEL. There was talk that Captain Buddington, of the Polaris, wilfully deserted the party; but Harron says: "I don't think Captain Buddington meant to abandon us; he either thought we could easily get ashore, or else he could not get through the ice; I don't think he would do anything of the kind; standing on the ship, you would naturally think we could get ashore; it may have looked to him that we were right under the lee of the shore; it is very likely that he thought we could get ashore, and that he didn't understand our signals." Further on Herron tells of numberless positions. His account reads: "Thursday, Nov. 28. — Thanksgiving to-day; we have had a feast — four pint cans of mock turtle soup, six pint cans of green corn, made into scouch. Afternoon, three ounces of bread and the last of our chocolate — our days' feast. All well." The next day, the 29th, they did not fare so well; they had to be content with boiled seal-skin; but the thickness of the hair baffled the masticatory powers of some of them. Further extracts from the same source show the straits they were reduced to: "December 2. — No open water has been seen for several days; cannot catch anything. Land has been seen for several days; cannot determine what shore it is, E. or W. It has been so cloudy that we cannot select a star to go by; some think it is the E. land; for my part, I think it is the W. Boiled some seal-skin to-day and ate it — blubber, hair and tough skin. The men ate it; I could not. The hair is too thick, and we have no means of getting it off. "December 5. — Light wind; a little thick; 15° below zero. A fox came too near to-day; Bill Lindemann shot him; skinned and cut him up for cooking. Fox in this country is all hair and hair. "December 6. — Very light wind; cold and clear. The poor fox was devoured to-day by seven of the men, who liked it; they had a mouthful each for their share; I did not think it worth while, myself, to commence with so small an allowance, so I did not try Mr. Fox. Last night fine northern lights. "December 8. — All in good health. The only thing that troubles us is hunger — that is very severe; we feel sometimes as though we could eat each other. Very weak, but, please God, we will weather it all. "December 13. — Light wind; cloudy; 19° below zero. Hans caught a small white fox in a trap yesterday. The nights are brilliant, cold and clear. The scene is charming, if we were only in a position to appreciate it. "December 20. — Light wind; cloudy. Joe found a crack yesterday and three seals. Too dark to shoot. It is a good thing to have game underneath us. It would be much better to have them on the floe for starving men. "December 22. — Calm and clear as a bell; the best twilight we have seen for a month. It must have been cloudy or we are drifting south fast. Ouf spirits are up, but the body is weak; 15° below zero." They began now to count the days until they could expect the sun to shine forth, with how much joy we can partially imagine, when we recollect that for nearly three months he had hidden his glorious face, and they had been groping in the darkness of an Arctic winter. Herron tells of their Christmas: December 24. — Christmas Eve. We are longing for to-morrow, when we shall have quite a feast — half pound of raw ham, which we have been saving nearly a month for Christmas. A month ago our ham gave out, so we saved this for the feast. Yesterday, 9 degrees below zero; to-day, 4 degrees above zero. "December 25. — This is a day of jubilee at home, and certainly here for us; for besides the approaching daylight, which we feel thankful to God for sparing us to see, we have quite a feast to-day — one ounce of bread extra per man, which made our soup for breakfast a little thicker than for dinner. We had soup made from a pound of seal blood, which we had saved for a month; a two-pound can of sausage meat, the last of the canned meat; a few ounces of seal, which we saved with the blood, all cut up fine; last of our can of apples, which we saved also for Christmas. The whole was boiled to a thick soup, which I think was the sweetest meal I ever ate. This, with half pound of ham and two ounces of bread, gave us our Christmas dinner." As Spring came on the experiences became dreadful. Herron says: "April 5. — Blowing a gale from the N. E., and a fearful sea running. Two pieces broke from the floe. We are on one close to the ten. At 5 a. m. removed our things to the centre. Another piece broke off, carrying Joe's hut (just built) with it; luckily, it gave some warning, so that they had time to throw out some things before it parted. A dreadful day; cannot do anything to help ourselves. If the ice break up much more, we must break up with it; set a watch all night. "April 6. — Wind changed to N. W.; blowing a very severe gale. Still on the same ice; cannot get off. At the mercy of the elements. Joe lost another hut to-day. The ice, with a roar, split across the floe, cutting Joe's hut right in two. We have but a small piece left. Cannot lie down tonight. Put a few things in the boat, and now standing by for a jump; such is the night. "April 7. — Wind W. N. W.; still blowing a gale, with a fearful sea running. The ice split right across our tent this morning at 6 a. m. While getting a few ounces of bread and pemmican we lost our breakfast in scrambling out of our tent, and nearly lost our boat, which would have been terrible. We could not catch any seal after the storm set in, so we are obliged to starve for a while, hoping in God it will not be for a long time. The worst of it is we have no blubber for the lamp, and cannot cook or melt any water. Everything looks very gloomy. Set a watch; half the men are lying down, the others walking outside the tent. "April 8. — Last night, at twelve o'clock, the ice broke again between the tent and the boat, which were close together — so close that a man could not walk between them. There the ice split, separating the boat and tent, carrying away boat, kayak and Mr. Meyer. There we stood, helpless, looking at each other. It was blowing and snowing, very cold, and a fearful sea running. The ice was breaking, lapping and crushing. The sight was grand, but dreadful to us in our position. Mr. Meyer cast the kayak adrift, but it went to leeward of us. He can do nothing with the boat alone, so they are lost to us unless God returns them. The natives went off on a piece of ice with their paddles and ice-spears. The work looks dangerous; we may never see them again. But we are lost without the boat, so that they are as well off. After an hour's struggle we can make out, with what little light there is, that they have reached the boat, about half a mile off. "There they appear to be helpless, the ice closing in all around, and we can do nothing until daylight. Daylight at last — 3 a. m. There we see them with the boat; they can do nothing with her. The kayak is the same distance in another direction. We must venture off; may as well be crushed by the ice and drowned as to remain here without the boat. Off we venture, all but two, who dare not make the attempt. We jump or step from one piece to another as the swell heaves it and the ice comes close together, one piece being high, the other low, so that you watch your chance to jump. All who ventured reached the boat in safety, thank God! and after a long struggle we got her safe to camp again." "April 20. — The wind here from the northwest. Blowing a gale in the northeast. The swell comes from there, and is very heavy. The first warning we had — the man on watch sang out at the moment — a sea struck us, and washing over us, carried away everything that was loose. This happened at nine o'clock last night. We shipped sea after sea, five and ten minutes after each other, carrying away everything we had in our tent, skins and most of our bed-clothing, leaving us destitute, with only the few things we could get into the boat. There we stood from nine in the evening until seven next morning, enduring, I should say, what man never stood before. The few things we saved and the children were placed in the boat. The sea broke over us during .that night and morning. Every fifteen or twenty minutes a sea would come, lift the boat and us with it, carry us along the ice, and lose its strength near the edge and sometimes on it. Then it would take us the next fifteen minutes to get back to a safe place, ready for the next roller. So we stood that long hour, not a word spoken, but the commands to "Hold on, my hearties; bear down on her; put on all your weight," and so we did, bearing down and holding on like grim death. Cold, hungry, wet and little prospect ahead." The crisis seemed to be rapidly drawing near. Their little ice-cake, already too small for the erection of a hut on it, was wasting away hourly, and at last, on the 25th, the gale reached them, and they were compelled at great risk to embark again in their boat. They were forced back to the floe, however. At the end of April a steamer appeared. Herrons tells of it thus: "April 28, — Gale of wind sprung up from the west. Heavy sea running; water washing over the floe. All ready and standing by our boat all night. Not quite so bad as the other night. Snow squalls all night and during forenoon. Launched the boat at daylight (3.30 a. m.), but could get nowhere for the ice. Heavy sea and head wind; blowing a gale right in our teeth. Hauled up on a piece of ice at 6 a. m. and had a few hours' sleep, but were threatened to be smashed to pieces by some bergs. They were fighting quite a battle in the water, and bearing right for us. We called the watch, launched the boat and got away, the wind blowing moderately and the sea going down. We left at 1 p. m. The ice is much slacker, and there is more water than I have seen yet. Joe shot three young bladder-nosed seals on the ice coming along, which we took in the boat. 4.30, steamer right ahead and a little to the north of us. We hoisted the colors, pulled until dark, trying to cut her off, but she does not see us. She is a sealer, bearing southwest. Once she appeared to be bearing right down upon us, but I suppose she was working through the ice. What joy she caused! We found a small piece of ice and boarded it for the night. Night calm and clear. The stars are out the first time for a week, and there is a new moon. The sea quiet, and splendid northern lights. Divided into two watches, four hours' sleep each; intend to start early. Had a good pull this afternoon; made some westing. Cooked with blubber fire. Kept a good one all night, so that we could be seen." The morning of the 29th Herron says: — "Morning fine and calm; the water quiet. At daylight sighted the steamer five miles off. Called the watch, launched the boat and made for her. After an hour's pull gained on her a good deal." And they finally reached the steamer and were rescued, in latitude 53:35. The vessel was the Tiqess, of St. John's, N. F. Sometimes polar explorers are able to save lives. The loss of the transport Bredalbane, in Aug. 21, 1853, near Cape Riley, was such an instance, the steamer Phoenix being the agent of rescue. Mr. Fowekher, agent for the Bredalbane, tells the story thus: About ten minutes past four the ice passing the ship awoke me. I put on my clothes, and on getting up, found some hands on the ice endeavoring to save the boats, but these were Instantly crushed to pieces. I went forward to hail the Phoenix, for men to save the boats; and whilst doing so the ropes by which we were secured parted, and a heavy nip took the ship, making her tremble all over, and every timber in her creak. I looked in the main hold, and saw the beams giving way; I hailed those on the ice, and told them of our critical situation. I then rushed to my cabin, and called to those in their beds to save their lives. On reaching the deck, those on the ice called out to me to jump over the side — that the ship was going over. I jumped on the loose ice, and, with difficulty, and the assistance of those on the ice, succeeded in getting on the unbroken part. After being on the ice about five minutes, the timbers in the ship cracking up as matches would in the hand, the nip eased for a short time, and I, with some others, returned to the ship, with the view of saving some of our effects. Captain Inglefield now came running toward the ship. He ordered me to see if the ice was through the ship; and, on looking down in the hold, I found all the beams, &c., falling about in a manner that would have been certain death to me had I ventured down there. It was too evident that the ship could not last many minutes. I then sounded the well, and found five feet in the hold; and whilst in the act of sounding, a heavier nip than before pressed out the starboard-bow, and the ice was forced right into the forecastle. Every one then abandoned the ship, with what few clothes he could save — some with only what they had on. The ship now began to sink fast, and from the time her bowsprit touched the ice until her mastheads were out of sight it was not above one minute and a half. From the time the first nip took her until her disappearance, it was not more than fifteen minutes." |