Kellscraft Studio, 1999 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click Here to return to Butterflies Content Page Click Here to return to the previous section |

(HOME) |

Kellscraft Studio, 1999 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click Here to return to Butterflies Content Page Click Here to return to the previous section |

(HOME) |

|

The true butterflies are so distinct in their structure and many of their habits from the Skippers that the most careful students of the order are pretty well agreed in making the two great superfamilies--Papilionoidea, the true butterflies, and Hesperioidea, the Skipper butterflies. The latter includes these two families: The

Giant Skippers (Megathymidae).

The Common Skippers (Hesperiidae). These insects as a whole are distinguished from the higher butterflies by their large moth-like bodies, small wings, hooked antennae (except in the Giant Skippers), by having five branches of the radius vein arising from the large central cell. The larvae spin slight cocoons in which to pupate and the pupae are rounded rather than angular. The two families are readily distinguished by the differences in their size and the structure of the antennae. The Giant Skippers measure two inches or more across the expanded wings and have comparatively small heads, with the clubs of the antennae not pointed or recurred. The Common Skippers are smaller, and have very large heads with the antennal clubs drawn out and recurved.

THE GIANT

SKIPPERS

FAMILY Megathymidae

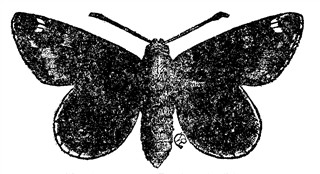

Although large in size, the Giant Skippers are few in numbers. Only one genus and five species are listed for North America, and practically all of these are confined to the Southwestern states and Mexico. Some of them extend as far north as Colorado and as far east as Florida. So far as the story of its life is concerned, the best-known species is the Yucca-borer Skipper (Megathymus yuccae) which was carefully studied by the late Dr. C. V. Riley. As will be seen from the picture above which represents the adult, natural size, this skipper has a body so large as to suggest some of the heavy-bodied moths. The wings are dark brown, marked with red-brown spots and bands. They fly by day and when at rest hold the wings erect.  Megathymus yuccae. Female. (After Riley.) These adults lay eggs upon the leaves of Spanish needle or yucca. The eggs soon hatch into little caterpillars which at first roll parts of the leaves into cylinders, fastening the sides in place by silken threads, and later burrow into the stem and root, often making a tunnel a foot or more deep. Here the caterpillars remain until full grown. They are then nearly four inches long and half an inch in diameter. They now pupate in the top of their tunnel and in due season emerge as adults. THE COMMON

SKIPPERS

FAMILY Hesperiidae

The Skippers are the least developed of the butterflies. They show their close relationship to the moths both by their structure and their habits. The larvae make slight cocoons before changing to chrysalids, and these chrysalids are so rounded that they suggest the pupae of moths rather than those of butterflies. The common name-Skippers--is due to the habit of the butterflies--a jerky, skipping flight as they wing their erratic way from flower to flower. In North America the Skipper family includes nearly two hundred species grouped in about forty genera. From this point of view it is the largest family of our butterflies, but on account of the small size and limited range of most of the species it has by no means the general importance of such families as the Nymphs, the Swallow-tails, or the Pierids. The Skippers are remarkable for the uniformity of structure in each stage of existence. The butterflies have small wings and large bodies. The broad head bears large eyes without hairs, but with a tuft of curving bristles overhanging each. The antennae are hooked at the end and widely separated at the base. Each short palpus has a large middle joint and a small joint at the tip. The fore wings project out at the front angle and the hind wings are folded along the inner margin. There are six well-developed legs in both sexes. The colors are chiefly various tones of brown, dull rather than bright, and many of the forms resemble one another so closely that it is difficult to separate them. The Skipper caterpillars have stout bodies and are easily known by the constricted neck. Most of these have the habit of making nests from the leaves of the food plants, weaving them together with silken threads. In a similar way each also makes a slight cocoon when it is ready to change to a chrysalis. The Skippers found in eastern North America are commonly grouped into two types--the Larger Skippers and the Smaller Skippers. The characteristics are given in the paragraph immediately following and the one on page 278. THE TRIBE OF THE LARGER SKIPPERS

The butterflies of this tribe have that part of the club of the antenna, which is recurred, about as long as the thicker part below it. As a rule, the abdomen is distinctly shorter than the hind wings. The caterpillars are rather short and thick, and the upper part of the head, when looked at from in front, is square or roundish rather than tapering. The chrysalids have the tongue case attached throughout its length and stopping short of the tips of the wing cases. The Silver-spotted Skipper

Epargyreus tityrus

One can seldom draw hard and fast artificial lines in nature. There are all sorts of intermediate conditions which disturb arbitrary classifications. It might seem simple enough to say that some insects are leaf-rollers and others are tent-makers, but as a matter of fact in the case of the Silver-spotted Skipper we have an insect which starts its larval life as a leaf-roller and finishes it as a tentmaker. Its life-history is rather interesting and easily observed, if one can find the larvae at work upon the leaves of locusts and other trees. (See plates.) The Silver-spotted Skipper is one of the largest butterflies of the interesting group to which it belongs. It lays its eggs upon the upper surface of the leaflets of locusts and other plants of the legume family. In less than a week each egg hatches into a little caterpillar with a very large head and a comparatively large body, tapering rapidly toward the hind end. This little creature cuts out from one side of the leaf a small round flap which it turns over and binds in place by silken threads to make a home for itself. This little home shows considerable variation in its construction but it usually has an arched dome held in place by strands of silk running from the eaten fragment to the surface of the leaf. It remains an occupant of this home until after the second moult. About this time it becomes too large for its house and deserts it to make a new one generally by fastening together two adjacent leaves. These are attached along the edges by silken strands in such a way as to give considerable room. It leaves one end open as a door out of which the caterpillar crawls to feed at night upon near-by leaves, returning to the house for shelter during the day. They continue to use this habitation until they are full grown as caterpillars and sometimes they change to chrysalids within it. More commonly, however, they crawl away both from the leafy case and the tree that bears it and find such shelter as they can upon the ground near by. Here they spin slight silken cocoons within which they change to chrysalids. In the more Northern states there is but one brood a year, so these chrysalids remain in position until early the following summer when they come forth as butterflies. Farther south there are two broods each summer, the second brood of butterflies appearing chiefly in August. The Silver-spotted Skipper derives its name from the distinct silvery spots upon the under-wing surface against a background of dark brown. The butterflies appear in the Northern states early in June and remain upon the wing for several weeks, being found even in August. They fly very rapidly and are difficult to catch in an insect net except when they are visiting flowers. This species is widely distributed, occurring from ocean to ocean over nearly the whole of the United States. It extends into Canada only in the eastern part and is not found in the Northwestern states. The Long-tailed Skipper

Eudamus proteus

This is perhaps the most easily recognized of all the Skippers found in the United States for it is the only one that looks like a Swallowtail. Its hind wings project backward as long, broad tails in a way that marks the insect at once as different from anything else. It expands nearly two inches and when the front wings are spread at right angles, the distance from the apex of the front wing to the end of the tail of the hind wing just about equals the expanse. The general color is dark brown, with about eight more or less rectangular silvery spots on each front wing. This is distinctly a tropical species which is common along the Gulf Coast from Mexico to Florida. It ranges north along the Atlantic Coast to New York City and even to Connecticut. In the South Atlantic states it is common, but toward the northern limits of its range it is very rare. In the West Indies this butterfly is very common and has been observed to rest with its wings vertical, the front ones held far back between the hind ones and the tails of the latter held at right angles to the plane of the wings. Apparently, this curious fact was first noted by Dr. G. B. Longstaff. Of course in museum specimens the wings have been flattened into the same plane during the process of drying, so that this peculiarity would not be noticed.

Juvenal's Dusky-wing

Thanaos juvenalis

There are few trees which have so interesting a set of insects attacking them as does the oak. It would be a simple matter to find abundant material for a large volume by making a study of the life-histories of the various insects that live upon or within the various tissues of this tree. The leaves alone provide a home for a remarkably large number of insect species scattered through a great many orders and families. The thickened blades seem to furnish an ideal opportunity for many larvae to get their living, and they are particularly useful to those which need to make a winter nest. By a little searching almost any time after the middle of June, one is likely to find a curious caterpillar home upon some of the oak leaves. The margin of the blade has been turned over, generally from above downward but sometimes from below upward, and has been fastened down to the main expanse of the blade by means of golden threads; commonly this fastening is not continuous but is more or less intermittent, so that the turned-over margin is likely to have an irregular border where it joins the blade. Inside of this tubular construction a rather unusual looking worm-like caterpillar is probably to be seen. Late in the season it will probably be nearly an inch long, with a smooth greenish body and a head that may be a bit brownish and more or less marked on the sides with orange tones. This is the larva of one of the most widely distributed Skippers--Juvenal's Dusky-wing. The species is found from southern New Hampshire west to the Great Plains and south to the Gulf of Mexico. In most localities it is seldom abundant but yet is so general that it may be found by almost every persistent collector. The wings expand about an inch and a half and are of a dull brownish color, more or less marked with darker and lighter spots. Toward the northern limits of its range there is but one brood a year but farther south there are two, although it is not improbable that some of the caterpillars of the first brood remain unchanged throughout the season, so that the insect is both single- and double-brooded in the same locality. The Yearly Cycle

The yearly cycle in southern New Hampshire may be taken as an illustration of the life of the species in regions where there is but one brood. The butterflies appear in open woods and on cut-over lands in May and June. They lay eggs upon the twigs of oak trees, one egg in a place and generally near a leaf stem. The egg soon hatches into a little caterpillar that crawls upon a near-by leaf and begins the construction of its tubular nest by bending over the margin and sewing it with golden silk. It utilizes this nest chiefly as a tent for resting and sleeping and wanders away from it generally to another leaf when it is ready to feed. It grows very slowly, having before it all the weeks of summer to complete its caterpillar growth. As it gets larger it needs a new tent and is likely to desert its early one. When it does this some observers have noted a curious habit. It cuts loose all the silk that binds the margin of the leaf down upon the blade so that the flap is free to spring back to its original position. It would be difficult to suggest an adequate explanation for this habit. When autumn comes our caterpillar is faced with the problem of passing through the winter successfully. It must shelter itself from birds, spiders, predaceous beetles, and many other enemies. It must find a means of keeping out of the reach of snow and rain, for while it can survive a great degree of cold as long as it keeps dry, it might easily be killed by freezing up with moisture. But the caterpillar is able to provide against these dangers. It has apparently an abundant supply of liquid silk to secrete from the silk glands in its head, so it lines its tubular tent with a dense silken web that effectually excludes enemies and moisture. It thus has on the outside of its nest the thick oak leaf and on the inside a dense soft lining that makes a most admirable winter protection. So it remains here throughout the winter, the leaf commonly staying on the tree until early spring. Then leaf, nest, and enclosed caterpillar are likely to drop to the ground to remain until spring arrives in earnest. Just what happens then seems to be a bit doubtful. The caterpillar changes to a chrysalis, but whether it first works its way out of its winter nest and makes a new and less dense covering seems not to be certainly known. Here is another good opportunity for some careful observations. At any rate, the caterpillar changes to a chrysalis, and late in spring it changes again to an adult butterfly that flits about on dusky wing for a few weeks before it dies. The Sleepy Dusky-wing

Thanaos brizo

The appearance of this butterfly both as to size and marking is very similar to that of Juvenal's Dusky-wing except that the white spots arc not present on the front wing of this species. The life-histories of the two species as well as their distribution seem to be closely parallel. The present butterflies are to be found early in summer in the same oak barrens as the other, the blueberry blossoms being freely visited for nectar by both species. Persius's Dusky-wing

Thanaos persius

This is a rather small, dark brown Skipper, with a few white spots toward the apex of the front wing, but otherwise not marked except for a very pale transverse band which is almost obsolete. The butterfly is found from ocean to ocean along the northern tier of states. It also occurs in the Eastern states as far south as Florida as well as in the states along the Pacific Coast. The food plants of the caterpillars differ from most of those of the other Skippers. The butterflies lay their yellowish green eggs, one in a place, upon the leaves of willows and poplars. These soon hatch into little caterpillars each of which cuts out a small flap along the margin of the leaf and folds it over, fastening it in place with silken threads. It thus forms a protecting nest within which it remains during the day, going forth at night to a neighboring part of the same leaf or to another leaf, and feeding upon the green surface tissues. In this first caterpillar stage it does not eat the veins to any extent. As it becomes larger it constructs a larger nest and feeds more freely upon the leaf tissues. When about half grown it has the curious habit of biting out small holes here and there in the blade so that the leaf takes on a very unusual appearance. The presence of these holes is generally the easiest way to find the caterpillars, for when the holes are seen, a little searching is likely to show one the characteristic tent-like nest. After a few weeks the caterpillars become full grown. They then sew themselves in for the winter, fastening all of the crevices in the nest so securely with silken webbing that a very serviceable winter cocoon is formed. An interesting fact is that this sewing up for the winter is likely to take place about midsummer, the caterpillars remaining quiet from this time until the following spring. The nests of course fall in autumn with the leaves and the caterpillars remain unchanged until April or May, when they transform into chrysalids to emerge in May as butterflies. There appears to be normally but one brood a year although there is some evidence of a partial second brood. The Sooty Wing

Pholisora catullus

This is one of the smallest of the blackish Skippers and may be known by its small size, expanding less than an inch, and the series of five white dots near the apex of the front wing, these dots being more distinct on the under surface. The species is widely distributed, occurring over practically the whole of the United States, except in the states along the Canadian border from Wisconsin west-and in several of these it is found along their southern limits. This butterfly is of particular interest because it is one of the comparatively few species that habitually occur in gardens and cultivated fields. The reason for this is that the eggs are laid upon white pigweed or lambs' quarter, the common garden pest of the genus Chenopodium. The eggs are laid singly, generally on the upper surface, and hatch in about five days into tiny caterpillars that make a little shelter for themselves by cutting out the edge of a leaf and folding over the blade, sewing it in place by a few silken threads. Here they remain and feed upon the green pulp of the succulent leaves either within the nest or near by outside. They remain in these cases until the time for the first moult, when they are likely to line the inside of the silken web before moulting. After this they make new cases for concealment and shelter, the cases as they grow older being generally made of two or more leaves securely bound together by silken web along their margin. When they become full grown, they spin a silken cocoon and change to yellowish green chrysalids from which the butterflies emerge a little more than a week later. This species is supposed to be double-brooded in the north. The full-grown caterpillars of the second brood sew up their leafy cases very carefully, making them of such thick silken webbing that they are watertight.: They remain in these coverings until the following spring, when each changes, still within the case, into a chrysalis from which the butterfly comes forth in April or May. THE TRIBE OF THE SMALLER SKIPPERS

In the members of this tribe the tip beyond the club* of the antenna is short and the abdomen is long enough to extend as far as or farther than the hind wings. The caterpillars have long and slender bodies with the upper part of the head, when looked at from in front, tapering rather than roundish or square. The chrysalids have the tongue-ease free at the tip and projecting beyond the tips of the wing-cases. The Tawny-edged Skipper

Thymelieus cernes

This is one of the commonest and most widely distributed of all our Skippers. It is found from Nova Scotia to British Columbia, south along the Rocky Mountains to New Mexico, Texas, and Florida. It is apparently absent west of the Rocky Mountains and along the Gulf Coast except in Florida. Its life-history was carefully worked out by Dr. James Fletcher, late entomologist to the Dominion of Canada, and in the north may be summarized thus: the butterflies come from the hibernated chrysalids in May or June. They remain upon the wing for several weeks so that worn specimens may be taken late in July or, rarely, even early in August. The females lay eggs upon grass blades. These eggs hatch about two weeks later, the larvae eating their way out of the shells so slowly that a whole day may be taken up by the operation. Each little caterpillar weaves a silken nest for itself, in which it remains concealed most of the time, reaching out to feed upon adjacent blades of grass but retiring into the nest at the least alarm. It is a sluggish little creature and grows so slowly that in the north it may require more than two months to become full fed as a larva. It is then about an inch long and has the characteristic outlines of the other Skipper larvae, with a black head and a greenish brown body. It now spins a cocoon, possibly using its larval nest as a basis, and some time later, before cold weather surely, it changes to a chrysalis that winters over. This is the story of the life of the butterfly in the more northern parts of its range. Even in New Hampshire there seems to be at least a partial second brood, and farther south there are probably two regular broods with the possibility that a small percentage of the first set of chrysalids remains unchanged until spring. The Roadside Skipper

Amblyscirtes vialis

This little butterfly is found apparently in most parts of the United States, as it has been collected in New England, California, Texas, and many intermediate points. Over the northern part of its range there is but one brood a year. In New Hampshire the butterflies appear in May and early June and lay eggs upon the blades of various grasses. These hatch about ten days later into slender, silk-spinning caterpillars, each of which makes a nest for itself by sewing together the margin of one or more grass blades. When the larvae get larger, they make larger and denser nests with heavy linings of silken web. After the earlier moults, the thin skin is covered with very fine snow-white hairs, between which there is developed a curious whitish exudation, so that the caterpillars have a flocculent appearance. When full grown, they change to delicate green chrysalids which apparently in the North remain until the following spring before disclosing the butterflies. In more southern regions there are two broods each summer. The Least Skipper

Ancyloxipha numitor

The Least Skipper differs from the other Skippers both in structure and habits. Most of these butterflies have thick bodies and a distinct hook at the end of each antenna. This has a slender body and the antennae lack the hook. Most Skippers have strong wings and show their strength in their rapid, erratic flight. This has feeble wings that show their weakness in their slow, straight flight. But from the fact that it is about the smallest of all our butterflies, expanding little more than three quarters of an inch, it deserves our interested attention. The tawny wings are so marked with broad margins of dark brown that they show the tawny tinge chiefly in the middle spaces. On account of its small size and its retiring habits this little butterfly is often overlooked by all but the most experienced collectors. It generally flies slowly just above the grass in sunny places in wet meadows and along the open margins of brooks and marshes. It rests frequently upon grasses, flowers, or bushes. Mr. Scudder noticed that when resting these butterflies have the curious habit of "moving their antennae in a small circle, the motion of the two alternating; that is, when one is moving in a forward direction, the other is passing in a reverse direction." This is the sort of observation that should challenge us all to sharper wits in watching living butterflies. It would be strange if no others thus twirled their feelers in their leisure moments. Who will find out? The female butterflies at least have something to do besides sipping the nectar of flowers or idly twirling their feelers. They must lay their eggs and thus provide for the continuation of the species; to do this they find suitable blades of grass on which they deposit their tiny, half-round, smooth yellow eggs. A week or so later each egg hatches into a dumpy little yellow caterpillar with a thick head and a body well covered with hairy bristles. This little creature is a silk spinner and makes a home instinctively by drawing together more or less the outer edges of a leaf blade and fastening them with transverse bands of silk. It then feeds upon the green tissues and as it grows larger it makes its nest more secure by thicker walls of silken web. When full grown as a caterpillar it changes into a slender chrysalis generally of a grayish red color, thickly dotted with black. About ten days later it emerges as a butterfly. The Least Skipper is one of the most widely distributed of all butterflies. It occurs from New England to Texas, south to Florida on the east coast, and west to the Rocky Mountains. THE END.

|