THE GOLDEN COBWEBS

A STORY TO TELL BY THE

CHRISTMAS TREE I am going to tell you a

story about something wonderful that happened to a Christmas tree like

this,

ever and ever so long ago, when it was once upon a time.

It was before Christmas, and

the tree was all trimmed with pop-corn and silver nuts and [name the

trimmings

of the tree before you], and stood safely out of sight in a room where

the

doors were locked, so that the children should not see it before it was

time.

But ever so many other little house-people had seen it. The big black

pussy saw

it with her great green eyes; the little gray kitty saw it with her

little blue

eyes; the kind house-dog saw it with his steady brown eyes; the yellow

canary

saw it with his wise, bright eyes. Even the wee, wee mice that were so

afraid

of the cat had peeped one peek when no one was by.

But there was some one who

hadn’t seen the Christmas Tree. It was the little gray spider!

You see, the spiders

lived

in the corners, -- the warm corners of the sunny attic and the dark

corners of

the nice cellar. And they were expecting to see the Christmas Tree as

much as anybody. But just before Christmas a great

cleaning-up began in the

house. The house-mother came sweeping and dusting and wiping and

scrubbing, to

make everything grand and clean for the Christ-child's birthday. Her

broom went

into all the corners, poke, poke, -- and of course the spiders had to

run.

Dear, dear, how the spiders had to run! Not one could stay in the house

while

the Christmas cleanness lasted. So, you see, they couldn’t see the

Christmas

Tree.

Spiders like to know all

about everything, and see all there is to see, and they were very sad.

So at

last they went to the Christ-child and told him all about it.

"All the others see the

Christmas Tree, dear Christ-child," they said; "but we, who are so

domestic and so fond of beautiful things, we

are cleaned up! We cannot see it, at all."

The Christ-child was sorry

for the little spiders when he heard this, and he said they should see

the

Christmas Tree.

The day before Christmas,

when nobody was noticing, he let them all go in, to look as long as

ever they

liked.

They came creepy, creepy, down the attic stairs,

creepy, creepy, up the cellar stairs, creepy, creepy, along the halls,

- and

into the beautiful room. The fat mother spiders and the old papa

spiders were

there, and all the little teenty, tonty, curly spiders, the baby ones.

And then

they looked! Round and round the tree they crawled, and looked and

looked and

looked. Oh, what a good time they had! They thought it was perfectly

beautiful.

And when they had looked at everything they could see from the floor,

they

started up the tree to see more. All over the tree they ran, creepy,

crawly,

looking at every single thing. Up and down, in and out, over every

branch and

twig, the little spiders ran, and saw every one of the pretty things

right up

close.

They stayed till they had

seen all there was to see, you may be sure, and then they went away at

last,

quite happy.

Then, in the still, dark

night before Christmas Day, the dear Christ-child came, to bless the

tree for

the children. But when he looked at it -- what do you suppose? -- it

was

covered with cobwebs! Everywhere the little spiders had been they bad

left a

spider-web; and you know they had been just everywhere. So the tree

was

covered from its trunk to its tip with spider-webs, all hanging from

the

branches and looped around the twigs; it was a strange sight.

What could the Christ-child

do? He knew that house-mothers do not like cobwebs; it would never,

never do to

have a Christmas Tree covered with those. No, indeed.

So the dear Christ-child

touched the spiders' webs, and turned them all to gold! Wasn’t that a

lovely

trimming? They shone and shone, all over the beautiful tree. And that

is the

way the Christmas Tree came to have golden cobwebs on it.

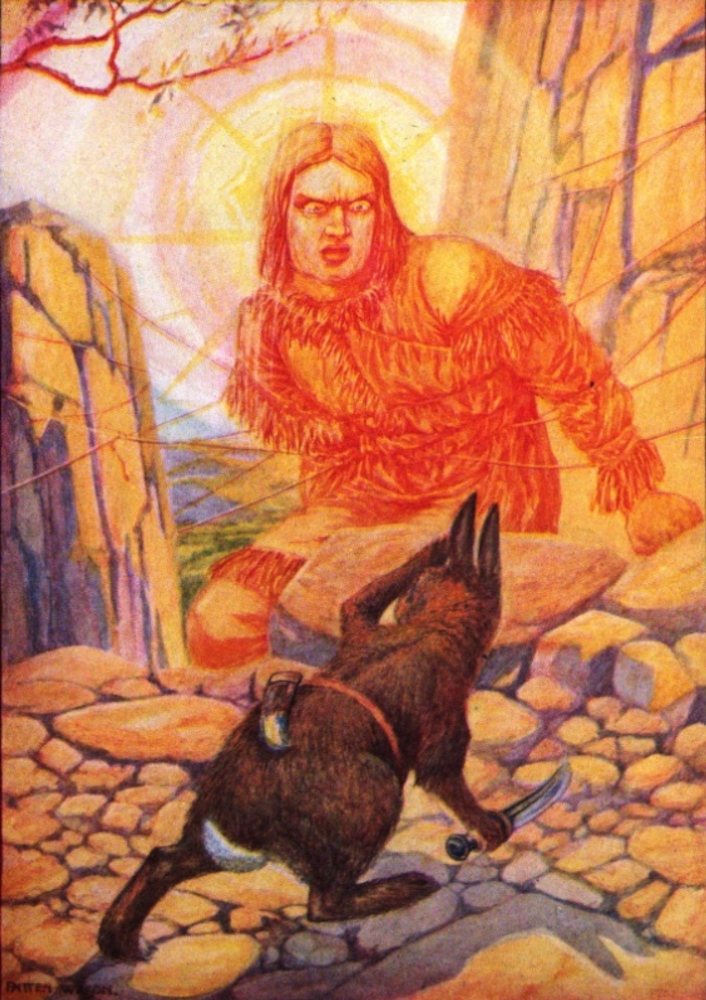

THE STORY OF LITTLE TAVWOTS

This is the story an Indian

woman told a little white boy who lived with his father and mother near

the

Indians' country; and Tavwots is the name of the little rabbit.

But once, long ago, Tavwots

was not little, -- he was the largest of all four-footed things, and a

mighty hunter.

He used to hunt every day; as soon as it was day, and light enough to

see, he

used to get up, and go to his hunting. But every day he saw the track

of a

great foot on the trail, before him. This troubled him, for his pride

was as

big as his body.

"Who is this," he

cried, "that goes before me to the hunting, and makes so great a

stride?

Does he think to put me to shame?"

"T'-sst!" said his

mother, "there is none greater than thou."

"Still, there are the footsteps in the

trail," said Tavwots.

And the next morning he got

up earlier; but still the great footprints and the mighty stride were

before

him. The next morning he got up still earlier; but there were the

mighty

foot-tracks and the long, long stride.

"Now I will set me a

trap for this impudent fellow," said Tavwots, for he was very cunning.

So

he made a snare of his bow-string and set it in the trail overnight.

And when in the morning he

went to look, behold, he had caught the sun in his snare! All that part

of the

earth was beginning to smoke with the heat of it.

"Is it you who made the

tracks in my trail?" cried Tavwots.

"It is I," said

the sun; "come and set me free, before the whole earth is afire."

Then Tavwots saw what he had

to do, and he drew his sharp hunting-knife and ran to cut the

bow-string.

But the heat was so great

that he ran back before he had done it; and when he ran back he was

melted down

to half his size! Then the earth began to burn, and the smoke curled up

against

the sky.

"Come again,

Tavwots," cried the sun.

And Tavwots ran again to cut

the bow-string. But the heat was so great that he ran back before he

had done

it, and he was melted down to a quarter of his size!

"Come again, Tavwots,

and quickly," cried the sun, "or all the world will be burnt up."

And Tavwots ran again; this

time he cut the bowstring and set the sun free. But when he got back

he was

melted down to the size he is now! Only one thing is left of all his

greatness:

you may still see by the print of his feet as he leaps in the trail,

how great

his stride was when he caught the sun in his snare.

TAVWOTS

... DREW HIS SHARP HUNTING-KNIFE AND RAN TO CUT THE BOW-STRING

TAVWOTS

... DREW HIS SHARP HUNTING-KNIFE AND RAN TO CUT THE BOW-STRING

THE PIED PIPER OF HAMELIN

TOWN

Once I was way over across

the ocean, in a country called Germany; and I went to a funny little

town,

where all the streets ran uphill. At the top there was a big mountain,

steep

like the roof of a house, and at the bottom there was a big river,

broad and

slow. And the funniest thing about the little town was that all the

stores had

the same thing in them; bakers' shops, grocers' shops, everywhere we

went we

saw the same thing, -- big chocolate rats, rats and mice, made out of

chocolate

candy. We were surprised about it after a while. "Why do you have rats

in

your stores? " we asked them.

"Don't you know this is

Hamelin town?" they said. "What of that?" said we. "Why,

Hamelin town is where the Pied Piper came," they told us; "surely you

know about the Pied Piper?" "What about the Pied Piper? we said. And

this is what they told us about him.

It seems that once, long,

long ago, that little town was dreadfully troubled with rats. The

houses were

full of them, the stores were full of them, the churches were full of

them,

they were everywhere. The people were

just about eaten out of house and home. Those rats,

They fought the dogs and

killed the cats,

And bit the babies in the

cradles,

And ate the cheeses out of

the vats,

And licked the soup from the

cooks' own ladles,

Split open the kegs of

salted sprats,

Made nests inside men's

Sunday hats,

And even spoiled the women's

chats

By drowning their speaking

With shrieking and squeaking

In fifty different sharps

and flats!

At last it got so bad that

the people simply couldn’t stand it any longer. So they all came

together and

went to the town hall, and they said to the Mayor (you know what a

mayor is?),

"See here, what do we pay you your salary for? What are you good for,

if

you can't do a little thing like getting rid of these rats? You just go

to work

and clear the town of them; find the remedy that's lacking, or -- we'll

send

you packing!"

Well the poor Mayor was in a

terrible way. What to do he didn’t know. He sat there with his head in

his

hands, and thought and thought and thought.

Suddenly there came a little

rat-rat at the door. Oh! how the

Mayor jumped! His poor old heart went pit-a-pat at anything like the

sound of a

rat. But it was only the scraping of shoes on the mat. So the Mayor sat

up, and

said, "Come in!"

And in came the strangest

figure! It was a man, very tall and very thin, with a sharp chin and a

mouth

where the smiles went out and in, and two blue eyes, each like a pin;

and he

was dressed half in red and half in yellow, -- he really was the

strangest

fellow! -- and round his neck he had a long red and yellow ribbon, and

on it

was hung a thing something like a flute, and his fingers went straying

up and

down it as if he wanted to be playing.

He came up to the Mayor and

said, "I hear you are troubled with rats in this town."

"I should say we

were," groaned the Mayor. "Would you like to get rid of them? I can

do it for you."

"You can?" cried

the Mayor. "How? Who are you, any way?"

"Men call me the Pied

Piper," said the man, "and I know a way to draw after me everything

that walks, or flies, or swims. What will you give me if I rid your

town of

rats?"

"Anything,

anything," said the Mayor. "I don't believe you can do it, but if you

can, -- I'll give you five thousand dollars."

"All right," said

the Piper, "it is a bargain."

And then he went to the door

and stepped out into the street and stood, and put the long flute-like

thing to

his lips, and began to play a little tune. A strange, high, little

tune. And

before three shrill notes the pipe uttered, You heard as if an army

muttered;

And the muttering grew to a

grumbling;

And the grumbling grew to a

mighty rumbling;

And out of the houses the

rats came tumbling!

Great rats, small rats, lean

rats, brawny rats,

Brown rats, black rats, gray

rats, tawny rats,

Grave old plodders, gay

young friskers,

Fathers, mothers, uncles,

cousins,

Cocking tails and pricking

whiskers,

Families by tens and dozens,

Brothers, sisters, husbands,

wives –

Followed the Piper for their

lives!

From street to street he

piped, advancing, from street to street they followed, dancing. Up one

street

and down another, till they came right down to the edge of the big

river, and

there the Piper turned sharply about and stepped aside, and all those

rats

tumbled hurry scurry, head over heels, down the bank into the river and - were - drowned. Every single last

one. Except one big old fat rat; he was so fat he didn’t sink, and he

swam

across, and ran away down south to live.

Then the Piper came back to

the town hall. And all the people were waving their hats and shouting

for joy.

The Mayor said they would have a big

celebration, and build a tremendous bonfire in the middle of the town.

He

asked the Piper to stay and see the bonfire, -- very politely.

"Yes," said the

Piper, "that will be very nice; but first, if you please, I should like

my

five thousand dollars."

"H'm, -- er --

ahem!" said the Mayor, "You mean that little joke of mine; of course

that was a joke" -- (You see it is always harder to pay for a thing

after

it is all used up.)

"I do not joke,"

said the Piper very quietly; "my five thousand dollars, if you

please."

"Oh, come, now,"

said the Mayor, "you know very well it wasn’t worth five cents to play

a

little tune like that; call it five dollars, and let it go at that."

"A bargain is a

bargain," said the Piper; "for the last time, -- will you give me my

five thousand dollars?"

"I'll give you a pipe

of tobacco, something good to eat, and call you lucky at that!" said

the

Mayor, tossing his head.

Then the Piper's mouth grew

strange and thin, and sharp blue and green lights began dancing in his

eyes,

and he said to the Mayor very softly, "I know another tune than that I

played; I play it to those who play me false."

"Play what you please!

You can't frighten me! Do your worst!" said the Mayor, making himself

big.

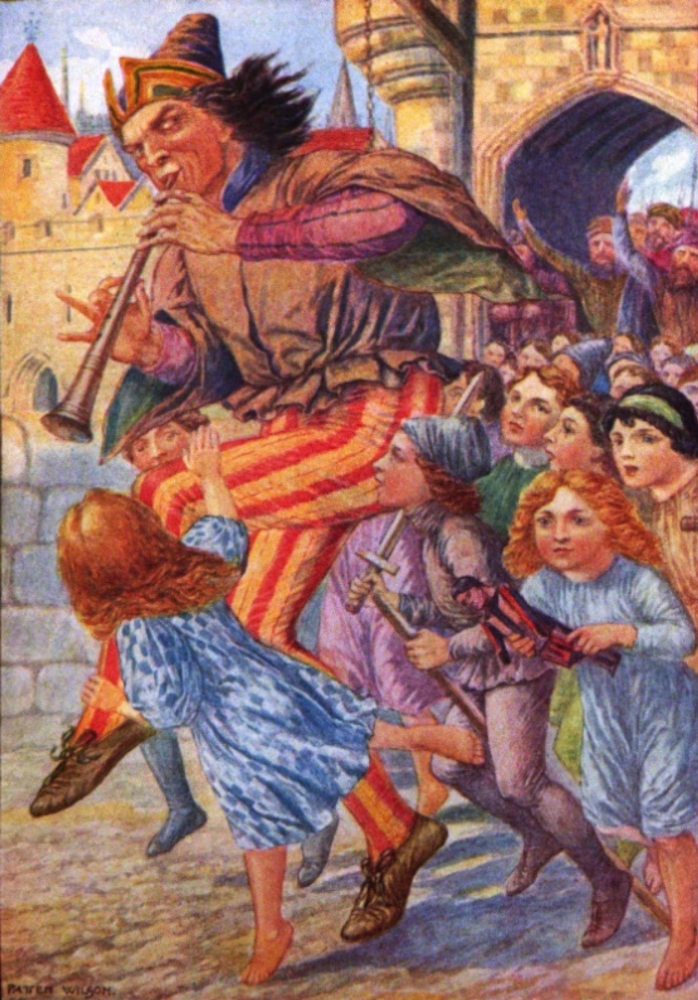

Then the Piper stood high up on the steps of the town hall, and put the

pipe to

his lips, and began to play a little tune. It was quite a different

little tune,

this time, very soft and sweet, and very, very strange. And before he

had

played three notes, you heard a rustling, that seemed like a bustling

Of merry crowds justling at

pitching and hustling;

Small feet were pattering,

wooden shoes clattering,

Little hands clapping and

little tongues chattering,

And like fowls in a farmyard

when barley is scattering,

Out came the children

running.

All the little boys and

girls,

With rosy cheeks and flaxen

curls,

And sparkling eyes and teeth

like pearls,

Tripping and skipping, ran

merrily after

The wonderful music with

shouting and laughter.

"Stop, stop!"

cried the people, "He is taking our children! Stop him, Mayor!"

"I will give you your

money, I will!" cried the Mayor, and tried to run after the Piper.

But the very same music that

made the children dance made the grown-up people stand stock-still; it

was is

if their feet had been tied to the ground; they could not move a

muscle. There

they stood and saw the Piper move slowly down the street, playing his

little tune,

with the children at his heels. On and on he went; on and on the

children

danced; till he came to the bank of the river.

"Oh, oh! He will drown

our children in the river!" cried the people. But the Piper turned and

went along by the bank, and all the children followed after.

Up, and up, and up the hill

they went, straight toward the mountain which is like the roof of a

house. And

just as they got to it, the mountain opened,

-- like two great doors, and the Piper went in through the

opening, playing

the little tune, and the children danced after him -- and -- just as

they got

through -- the great doors slid together again and shut them all in!

Every

single last one. Except one little lame child, who couldn’t keep up

with the

rest and didn’t get there in time. And they never came back anymore at

all,

never.

WITH

THE CHILDREN AT HIS HEELS

WITH

THE CHILDREN AT HIS HEELS

But years and years

afterwards, when the fat old rat who swam across the river was a

grandfather,

his children used to ask him, "What made you follow the music,

Grandfather?" and he used to tell them, "My dears, when I heard that

tune I thought I heard the moving aside of pickle-tub boards, and the

leaving

ajar of preserve cupboards, and I smelled the most delicious old

cheese in the

world, and I saw sugar barrels ahead of me; and then, just as a great

yellow

cheese seemed to be saying, 'Come, bore me' -- I felt the river rolling

o'er

me!"

And in the same way the

people asked the little lame child, "What made you follow the music?"

"I do not know what the

others heard," he said, "but I, when the Piper began to play, I heard

a voice that told of a wonderful country just ahead, where the bees had

no

stings and the horses had wings, and the trees bore wonderful fruits,

where no

one was tired or lame, and children played all day; and just as the

beautiful

country was one step away -- the mountain closed on my playmates, and I

was

left alone."

That was all the people ever

knew. The children never came back. All that was left of the Piper and

the rats

was just the big street that led to the river; so they called it the

Street of

the Pied Piper.

And that is the end of the

story.

|