|

CHAPTER VII

THE KERMESSE

GERARD and his little friends

began to make their preparations for going to the Kermesse. Their

parents had all given their consent as soon as they learned that the

school-master had promised to go with the boys to see that they did not

get into mischief.

Helda was the only one who had any troubles left. She, too, wanted very

much to go to the Kermesse. How could it be managed? She knew that it

was useless to worry Aunt Ursula about it, but the good lady knew well

what Helda had on her mind, for though she was usually as lively and

chirpy as a bird she now went about with a very thoughtful and sad

face. Aunt Ursula said nothing, thinking it better to let Helda find a

way out of her difficulty herself.

After much thought Helda wrote a very blotty, but nice, little letter

to her family asking why her papa and mamma would not like to go to the

Kermesse and take her along, too. She then carefully directed the

envelope to Mynheer Shorel, Bruges, and dropped it into the letter box

by the great gate of the Beguinage.

But alas! Papa Shorel wrote back and said that while he would like

nothing better than to give his little daughter pleasure and that he

and her mamma would enjoy seeing a Kermesse again but -- and it was a

big BUT -- he was just in the midst of curing the flax and Helda would

know how busy they all were, and that neither he nor her mamma could

think of leaving home just at the present time.

Helda sighed. Yes, it was so. She had forgotten how very busy every one

was at the time of drying out the flax before it was put away in the

big storage lofts behind the house.

Helda's mother reread the letter and smiled over it and thoughtfully

set about to work out a plan. Helda's brother, Dirk, was soon coming

home from Antwerp, and he might stop on his way and take his little

sister for a day to the Kermesse. This decided, Vrouw Shorel wrote a

letter to Dirk and a letter to Helda, and you can imagine what a happy

little girl Helda was when she learned how it had all been arranged.

Just before the Kermesse Dirk came. He had grown so tall and looked to

Helda so like a grown man, and he probably felt that he was one too,

though he was only fifteen. Helda thought he was a wonderful brother as

she listened to his tales about Antwerp, the fine old city, with its

beautiful old cathedral with its tall tower and the old buildings and

the valuable pictures. Ships come and go from every port of the world

to the very city gates. Helda listened attentively as Dirk told of the

great warehouses and the wealthy merchants and valuable cargoes from

over-seas that were piled up on the quays. Dirk himself had walked

between piles of ivory tusks of elephants, out of which all sorts of

ivory things were carved, and had seen bales and bales of rubber from

the great African forests.

Dirk said that when he had finished school he was going to work in the

office of one of the great Antwerp merchants who dealt in rubber.

"These merchants of Antwerp are rich men," said Dirk. "I am going to be

a merchant in Antwerp myself some day, and Helda, you can come and live

with me and keep house for me," finished up the big boy, grandly. And,

of course, Helda said she would, and forgot for the time all about her

wish to become a Beguine.

On the day of the Kermesse there were no laggards at the train that was

to take them to Ostend. The little band had clubbed together to share

all the expenses and buy the tickets. The train was crowded with

holiday-makers for the Kermesse at Ostend was always a very popular

event, the city being situated right on the sea. It was with some

little difficulty that all our little friends found seats but finally

they were all placed. Dirk and Helda with Saskia, whom Helda had

brought with them. Gerard hugged his violin case in his arms, and the

rest of the boys, with freshly scrubbed faces and in their best

clothes, fairly brimmed over with glee.

It was not long before they were at Ostend. Everything was very gay,

everywhere were garlands and flags flying. Booths were set up on either

side of the streets and there were tents for the dancers in the middle

of all the Kooters. Already there were such crowds swinging up and down

the streets that the children found if hard to make their way and keep

together. Gerard would never have been able to find his way but for the

help of the school-master, who piloted him to the tent where he was to

play for the dancing. Here Gerard was installed on a high wooden seat

half hidden in the greenery and bunting and soon began to play to let

the people know that the dancing was about to commence. He felt a

little strange at first, especially when his friend the school-master

had to hurry away to look after the rest of the parry, but as soon as

he drew his bow across the violin all his shyness left him and he

played away so merrily that the couples at once began to come into the

tent and take their places on the sand-strewn floor.

Meanwhile, after listening to Gerard for a time, Dirk and Helda and

Saskia joined hands to keep from becoming separated and wandered about

just bent on having a good time. There were the usual amusements to be

found at a Belgian Kermesse, merry-go-rounds, shooting galleries,

places where fortunes were told, noisy mechanical melodeons grinding

out popular Flemish airs, and everywhere were stacks and stacks of

brown gingerbread.

It all seemed very marvellous to the children. Dirk was at first a

little high and mighty, and tried to tell them how much better it was

all done in Antwerp, but he soon forgot his dignity and entered into

all the fun with as much glee as did Helda and Saskia.

When it was time for luncheon they went back for Gerard, who was then

released from his duties until later on in the afternoon.

The whole party gathered on the beach where they ate the lunch which

they had brought with them, and afterwards walked up and down the

Digue, a splendid promenade, or walk, which runs for more than a mile

along the shore, lined on one side by magnificent villas and hotels.

The best part of the day for the children was when the Archery Clubs

began their practice. There are numbers of clubs of archers in Belgium

to-day, as there have been for long years, for, in the old days, the

Belgian archers were a famous body of fighters. They defended their

country from invasion for hundreds of years.

"Are they not fine?" exclaimed Helda, as the archers were drawn up on

the shooting field before their targets.

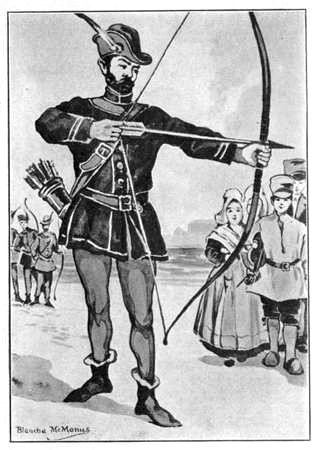

"THE ARCHERS WERE DRAWN UP ON THE SHOOTING FIELD BEFORE THEIR

TARGETS."

The archers wore green jerkins, or belted-in coats, leather knee

breeches and buskins, and little bonnets, or caps, of green, with a

feather on one side, were set jauntily on their heads. Each archer

carried a long bow just like the bows with which the ancient archers

were equipped, and slung over the shoulder was a leather case, or

quiver, which held the arrows.

By this time Gerard was playing to a much bigger crowd than in the

morning. Presently he saw a tall man with long black hair brushed back

from the forehead watching him from the other side of the tent. It was

the same man who had been beside the Burgomaster at the band

competition.

When the dance was finished the tall man walked over to Gerard and

said, "So you are a violinist as well as the leader of a band, my

little man. Who taught you to play the violin?"

Gerard then told him of his struggles to become a musician and how he

loved music, and how it was the dream of his life to be able to study

under the great master at Brussels.

The man's rather severe face softened as the little boy poured out his

story.

"You must have the chance," he said, when Gerard had finished his tale.

"You play better than you know, my little fellow."

He then took a card out of his pocket and wrote something on it and

handed it to Gerard. Gerard gasped when he read the name on the card.

It was that of the great violinist of Brussels. Not only the best in

Belgium, but one of the best in the world.

"You know that name, eh? " continued the tall man with half a smile.

Did Gerard know it? Did not every music lover in Belgium know it?

"Well, you must come to me in Brussels and I will see that you become

the violinist that you wish to be. It will cost you nothing, and I can

soon put you in the way of earning money. Now talk it over at home. The

directions on the card will tell you how to find me when you are ready

to come to Brussels. No, don't thank me" -- as Gerard began to stammer

-- "I am always looking for boys such as you. I see they are waiting

for you to begin again, so good-by for the present, and don't forget."

Before Gerard could utter a word the tall man had gone. Gerard was

dazed. How he went on playing he never knew. Was this really he, little

Gerard Maes? Was it not all a dream?

How the school-master ever managed to get his little charges together

again is difficult to tell, but it was finally accomplished and at dusk

the weary but happy little party of young folks found themselves on the

train homeward bound.

Some had their pockets stuffed with knickknacks which they had bought.

Dirk had a walking stick and Helda had bought a gingerbread lion for

Aunt Ursula. Karel had cut his thumb on a wonderful knife he had

bought, and every one had more or less sticky fingers and faces.

It was a sleepy lot that finally separated to go to their homes that

night, but Gerard and his mother sat up very late talking seriously

together.

Did Gerard's dream come true? Yes, it did. Gerard did go to Brussels to

study with the great violinist who had befriended him, and Aunt Ursula

loaned him enough money so that his mother might hire some one to help

her in his stead.

Gerard studied diligently in Brussels under his master, and worked so

hard that he was soon able to play at important concerts when he

commenced to make money seriously.

The very first money that he earned he sent to Aunt Ursula to repay her

loan, and he was soon able to send some to his mother, too, but the

first time that he had any left over for himself he bought a fine,

young, strong dog for the cart so that good, faithful old Hugo could

rest from his long hard work and sleep on a mat before the door and do

nothing, like a real house dog.

Little Helda's dream came true, too. She made great progress in her

work and became a maker of beautiful lace like Aunt Ursula, so that the

visitors who came to buy lace of the Groot Jufvrouw almost always chose

some from the stock made by Helda.

And you will be glad to know that the little band prospered under

Karel's leadership, and that Hubert became an excellent carpet weaver

and a fine young fellow.

THE END.

|