| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2009 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

|

Chapter

III

Of

the Renewal of War — Mr. Williams' Apprehension and the Warning of

Col. Schuyler — The Superstitions of the Times — The Winter March

of the Invaders — The Bell of St. Regis — The Attack on the Town

— The Old Indian House

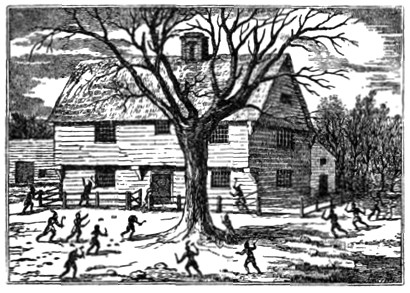

AS has been said France and England were for nearly three-quarters of a century almost continually at war, and there was a feeling of intense hostility between their colonies over the seas, even when there was no armed expedition in the field. Under the pretext of protecting the eastern Indians from English encroachment the French were constantly inciting them to marauding the New England frontiers. In 1703 plans were laid to cut off the outlying English settlements from one end of New Eng land to the other, but these plans were not fully executed. Many eastern settlements were destroyed, but those on the western borders remained unmolested It is true there were rumors of an expedition against Deerfield, and Rev. Mr. Williams was so apprehensive of danger that he applied to the government of the province to detail a guard for the town, on which twenty soldiers were sent for a garrison. Besides, the minister sufficiently roused his people so that they strengthened the fortifications, but the danger was not as clearly realized as it should have been. What was known of the intentions of the enemy came from Col. John Schuyler at Albany, who was in the habit of get ting such intelligence from the Indians trading in that place. The Indians who furnished him information were Mohawks who knew of Canadian affairs through a band of their relatives settled at what was then called Saint Louis, now Caughnawaga, nine miles above Montreal. The latter had been converted by the Jesuits and persuaded to emigrate and settle on the St. Lawrence where they naturally allied themselves with the French. Deerfield, at that time, except for a few families at Northfield, was the most northerly settlement on the Connecticut river. It was perfectly easy for the enemy to approach it unawares, and there was in the air a feeling that some untoward calamity was brewing. It was an age of superstition. Women were hung for witches in Salem, and witch craft was believed in everywhere. Did the butter or soap delay their coming, the churn and the kettle were bewitched. Did the chimney refuse to draw, witches were blowing the smoke down the flue. Did the loaded cart get stuck, invisible hands were holding it. Did the cow's milk grow scant, the imps had been sucking her. Did the sick child cry, search was made for the witches' pins. Ideas of this sort and the tales told to illustrate them so worked on the minds of the people that adults, as well as children, were ready to see a ghost in every slip of moonshine and trace to malign origin every sound that broke the stillness of the night — the rattle of a shutter, the creak of a door, the moan of the winds or the cries of the beasts and birds.  For two or three evenings previous to February 29th, 1704, a new topic of supernatural interest had been added to the usual stock. Ominous sounds had been heard in the night, and, says Rev. Solomon Stoddard, "the people of Deerfield were strangely amazed by a trampling noise around the fort, as if it was besieged by Indians." The older men recalled similar omens before the outbreak of Philip's war, when from the clear sky came the sound of horses' hoofs, the roar of artillery, the rattle of small arms, and the beating of drums to the charge. These tales of fear were in everybody's mouth, and even the thoughtful were possessed with an undefinable dread. At that moment, just beyond the northern horizon, their foes were on the southward march bent on overwhelming the settlement. A horde of Frenchmen turned half Indian, and savages armed with civilized powers of destruction were hurrying towards our doomed frontier over the dreary waste of snow which stretched away for hundreds of miles to the St. Lawrence. This expedition, under the command of Hertel de Rouville, advanced by way of Lake Champlain, which they left near the present city of Burlington to follow up the Winooski river. From the head waters of this stream they passed through a gap in the Green Mountains, came down the valley of White river, then for a long distance traveled southward on the frozen Connecticut. In the dark shades of some ravine, a day's march nearer our border, each night their camp was pitched and kettles hung. Their fires lighted up the mossy trunks and overhanging branches of the giant hemlock and towering pine, throwing their summits into a deeper gloom, and building up a wall of pitchy darkness, which enclosed the camp on every side. A frugal supper, and quiet soon reigned within this circle, and around each camp fire the tired forms of the invaders were stretched on beds of evergreens, to be up at dawn, and, after a hasty breakfast, onward again. Dogs with sledges aided to transport the equipage of the camp, and the march was swift. The final day came and dogs, sledges and such baggage as was not needed were left behind, while the army pushed forward over the last miles of the journey with celerity and caution, and reached a pine-clad bluff overlooking the Deerfield Valley on the night of February 28th. Here, behind a low ridge, the packs were unstrapped, the war paint put on, and all preparations made. One tradition has it that the object that brought these three or four hundred French and Indians all this winter journey from their northern homes was the capture of the bell in the village church. They were moved by righteous indignation, for this bell had been taken by a colonial privateer from a French vessel while on its way to a Catholic church in Canada. It is said further that the invaders, after securing the bell, dragged it away on sledges to Canada, and that there, in a little church in St. Regis, it calls the worshipers to service to this day. Several times since its capture, so the story goes, efforts have been made by Deerfield people to have the bell re turned, and negotiating committees have made the pilgrimage to St. Regis with this end in view. But the French will not part with the bell, and if it ever comes back it will come as it went — the spoils of war. The enemy lay in concealment on the bleak ridge two miles north of the town till the darkest hour of the night came — that preceding the first grayness of morning. Then they crept in on the sleeping village. It was midwinter and the slight defence of palisades was in many places drifted over with snow. More than that, a stiff crust had formed on the snow sufficient to bear the weight of a man, and the enemy left their snow shoes behind at the borders of the meadow that intervened between their hiding place and the village. The town sentinels proved unfaithful. They had retired shortly before, and there was no alarm given at the enemy's approach. The savage foe came noiselessly over the palisades at the northwest corner, where the winter winds had lifted the highest drifts, and distributed themselves among the peaceful homes. Then came the dreadful warwhoop, the blows of axes on resisting doors, the leaping of flames and the report of muskets. Only two houses — one within the palisades and another outside — made a successful resistance, and except for the occupants of these and a few who escaped to the woods, the rest of the inhabitants were either killed or captured. There was no time to fly to the garrison house, in which lived Captain John Sheldon, for it was surrounded by the savages in the first onslaught. Its door was heavily bolted and the savages, finding they could not push it in by main force, hacked a hole with their tomahawks, then thrust a musket through the aperture and fired and killed the captain's wife. The captain's son leaped from a chamber window, gained the shelter of the woods and escaped to Hatfield. Soon the garrison house fell into the hands of the foe, and as it was one of the largest in the place, they used it as a depot for the prisoners they were fast collecting.  The

house that made the stoutest fight was one about fifty yards distant

from Sheldon's, where were seven armed men and several women. While

the men fired on the savages the women loaded their guns or cast

bullets for future use, and after various attempts to take the house

by stratagem or burn it, the enemy gave their attention to keeping

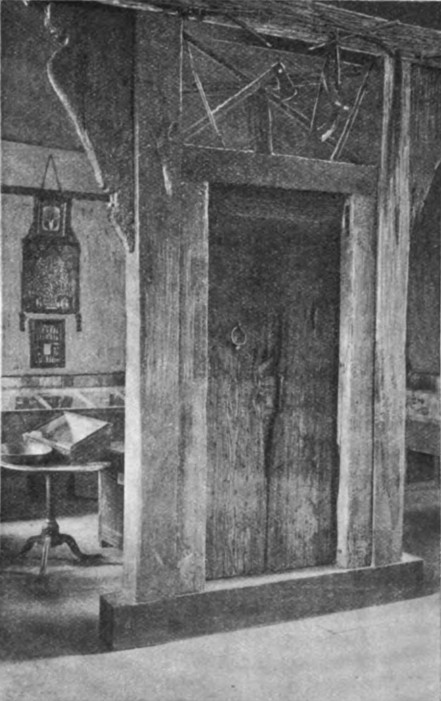

out of range of the defenders' shot.  The Door of the Old Indian House

At the end of the fight the only two houses within the palisades that were not smoking ruins were the one so bravely defended and the garrison house. The latter had been pillaged, and when the enemy began their retreat they set it on fire, but it was saved by the efforts of the few English who had escaped death and capture and were still in the village. This building, as time went on and the events of this February night receded into the past, came to be known as "The Old Indian House." It stood in its wonted place till 1848, when in its mossy and loose-clapboarded old age it was torn down. Even then its sills and other timbers were as sound as when the house was first erected. The old door, filled with nails and gashed by Indian tomahawks, has luckily been preserved, a most interesting relic, with a few other fragments of the house, in the Deerfield Museum. |