| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2012 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

| CHAPTER

VI

HOUSEBUILDING IS JUST ONE THRILL AFTER ANOTHER NO one ever watched his house grow from the foundations without first being disappointed in its size; it always looks so small. When you have all outdoors to compare your foundation with, it suffers from the comparison, like the hero of the Johnstown flood when he first met Noah in heaven. But don't let this disturb you. Don't say to yourself, '*Did that architect gyp me after all? This isn't going to be a house, it's more like a pen for a flock of Bantam chickens. Where is the piano going? How in the world will Uncle Podger ever fit in our guest room when he comes on to visit us at Christmas'?" Cellar foundations always look small. But a foot is a foot. Don't ever forget that. By this time you have your plans. If you are wise you made your little paper model before you had plans made. So just possess your soul in patience and wait for the next blow. As the frame starts to go up, the house begins to look like a piano box. You wonder whether there will be enough 2 x 4's — as the upright studs are called — left in the world to build another house after yours is finished. There are millions of them — and they are never pretty. Then the carpenters put on the roof rafters. Now it does begin to look a little like the house of your dreams. It has acquired some shape and size over night. But the beginning of a house is a trying experience. Before starting to build, we had acquired a large file of building material literature. Catalogs make a fascinating library when you really are planning a home. Housebuilding magazines are full of advertisements relating to homes. Send for the catalogs. That is what they are for — woodwork, doors, plumbing fixtures, electric fixtures, hardware, shingles, paints, furnaces. Frequently you will get some facts more specific than those your architect has acquired. He may prefer to read Mencken's Mercury or the New Yorker, and deem a perusal of house-building catalogs as unworthy of a graduate of Beaux Arts. He may have utterly missed the fact that Sears Roebuck have a type of early six-panel doors at low cost nearly as good as those a mill will charge you $20. apiece to make. The first real blow our own house produced was when sidewalls were up and carpenters were shingling the roof. Then any house should give some indication of what it would ultimately look like. But what in the world had happened to that low, squatty ''out of the ground like a mushroom" look that was so characteristic of the paper model? This house wasn't a mushroom. It was a bean pole. Its terrible ridge reared its head high above the trees like a barn on a bleak hill. Far down in the cellar, masons were pottering around on fireplace foundations, big enough it would seem to support one end of Brooklyn Bridge. In a few days the rough brickwork of the fireplace was finished and the chimney wormed its way through the second floor and disappeared into the attic. It happened that we did not see the house for a few days. When we did, the chimney was finished. It had worked a miracle. Gone was that awful leggy look, suggestive of military barracks. The chimney proved itself to be the keynote that made everything else harmonize. When you come to think about it, the main difference between any barn and an early New England farm-house is the chimney. But in settling the chimney detail is where so many people fall down. What are houses going to look like when chimneys are no longer necessary? With electric ranges and gas-fired boilers, chimneys are almost unnecessary now except for fireplaces. Electric household heat is going to be the next step with each room thermostatically heated by an electric radiator built into the wall. Without chimneys, houses are going to look as much alike as taxicab drivers — and to my notion be just as ugly. You can't tell much about a house until you live in it. Sometimes features you admired the most in the plans don't seem so good in the house. We have lived in this house long enough to know that it is just as practical and livable as a house modeled on modern lines. It is true that almost every detail was thought out in advance, but that is due to a firm conviction of mine that most of the mistakes people make in building are due more to laziness than to things that couldn't have been foreseen. It doesn't require an architect to tell you in advance what will happen to your furniture, for example, when it gets in a new setting. Just take your floor plans and make little cardboard models of your furniture drawn to the same scale. Suppose you plan to furnish a bedroom with twin beds, a dresser, a small table, a chest of drawers, arid a chair or two. Your beds 6' 6" X 4 feet in quarter scale become 9/16 inches by 1 inch, your two foot by three foot dresser is ½ x 3/4 inches. Label the little card "beds," "dresser" "table," etc. Then place them in the room. You can see whether they will fit, or whether they overlap windows, get in the way of electric switches, or in any way promise to make a nuisance of themselves. You can also plan the places to have baseboard outlets for table or bridge lamps. You can decide whether a closet door will swing right or left to be the most convenient for you. Mistakes which develop from too few hours spent with plans can be caught and corrected then, merely by changing a few lines. But, once your house is built, they mean ripping out partitions, or, what is more likely to happen, enduring some inconvenience for the next twenty years. Merely to show how carefully advance planning can be made, I found that to place my kitchen sink where I wanted it, would leave only a scant 1/4 inch leeway for the ice-box door to swing past it. But I also found that the type of ice-box I wanted was made exactly to size. I did not even take the clerk's word for it. I measured several myself in the showroom. When the box arrived it fitted perfectly. True, there is but a quarter inch. But a miss is as good as a mile. One favorite building nightmare doesn't require the services of Freud to analyze: it is found in the stupid placing of electric light switches. I don't suppose any house was ever built with all switches in the proper place. And yet there is an exceedingly simple rule to follow. Place your switches where you expect to find them in the dark. Remember the story of the village nitwit who found the lost cow when the whole village had searched in vain. He said, "I just thought ef I wuz a cow, where I would go, and I went there and there she wuz." If you were a stranger in your own house where would you expect to find switches? Well that is the place to put them. First and second floor hall switches should be controlled two ways, so that you can light either from both floors. By fairly close calculations, I estimate that I might have traveled up and down stairs seventeen miles in a year, by omitting a first floor central switch upstairs and by forgetting to put out the lower hall light until I reached the second floor. As this book, to have an excuse for existence, is supposed to help prospective house builders, I will tell about one mistake we made and how it occurred. To get the job started promptly, we let the contract for the cellar before we had any bids on the house itself. A contracting mason with a large force of men was operating in my vicinity. I showed him the cellar plan which called for a cellar foundation 26 x 38 with certain wing walls in addition. He made me a bid of $675.00 for digging the cellar and building the walls; fair enough! We made a verbal agreement that I was to pay for necessary blasting of large rocks. There was no written agreement for anything. This contractor, instead of putting on his own force of men, promptly sublet the cellar digging to a local garage mechanic temporarily out of work and the garage man hired an old darkey and thus the cellar was started. Before they had gone far into the ground they ran into a stratum of hard pan that scarcely yielded to the pick at all. It was the hardest *!-##-*! hard pan, to quote the subcontractor, that he ever saw. Naturally he soon became discouraged. The real contractor, with whom I had dealt, kept studiously away. I alone had to listen to the daily tale of woe from the subcontractor. After about three weeks he called the job done. The cellar bottom was completely covered with boulders ranging in size from a pumpkin to a bale of hay. There were certainly a lot of them. The house is built on what geologists describe as a lateral moraine of the great glacier which picked up all the loose rocks of Hudson's Bay a few million years ago and dropped them along the way as far south as Kentucky. The subcontractor claimed that I had agreed to blast all the rocks that two men could not lift. There were at least twenty-five such rocks in my cellar. I contended that this proposition was manifestly absurd. I cited legal authorities to the effect that in excavating work, a rock isn't considered a subject for blasting unless it contains at least a cubic yard of material. But he was stubborn and I wanted my house, so I hired a team which, with a chain and a man who knew his business, snaked out every rock but three in a single morning and rolled them down the bank where they made a mighty splash into the river. Then we got into another jam about the foundations. The contractor squealed about building the necessary retaining walls, claiming that he had agreed to build only one. There were two, so I asked him who was to build the other. He didn't seem to have an answer for that, neither had I. So I paid him for digging the cellar and discharged him. That was my building nightmare. It doesn't seem so bad now. Next to the plan of a house, the most important thing to decide is, who is to build it. It is customary to submit plans and specifications to several contractors. It is also considered ethical to award the job to the lowest bidder. But the lowest bidder is not always the best man. Sometimes, if he discovers later that his bid was too low, he may slight the work or attempt to make substitutions at the finish. It is a pretty safe rule not to invite bids from anyone to whom you would not award the contract. An early American home requires different treatment from the ordinary house. If I built another I wouldn't award the job to any contractor, irrespective of his bid, unless he had real enthusiasm for this type of house. I can't imagine anything more discouraging than the contractor who meets your idealism with a shrug of the shoulders or a breath of garlic. Some changes are almost always necessary no matter how carefully you have planned. But a straight shooter is always willing to meet his customer half way on any changes, even if he is a contractor. Never forget that architects and contractors are merely in a state of armed truce. They are rarely friends. Contractors like to pick flaws in plans and to show up the architect whenever they can. Your architect is the go-between in disputes. He is a valuable man. No contractor likes to have wholesale alterations made in plans. I have built a number of houses without a definite estimate. The so-called ''cost plus" plan is very good if you know approximately what your house will cost from the cost of similar houses in your neighborhood. In ordinary houses there is a fairly close limit for plumbing and heating costs. The same is true of painting, woodwork and hardware. But in early houses there is so much built-in woodwork and such unusual hardware and floors, that past experience will not serve. Up to the point where the frame is up and a house is ready for the plastering, there is comparatively little opportunity to botch things, but after that is the time when the wood-butcher gets in his work. When your floors are laid, your doors and windows trimmed and cabinet work installed, defects begin to appear which might take but a few minutes to correct, but which will be an eyesore for years if they are not corrected. You can be sure with any new house, windows and doors are bound to stick. Every house should have a little expert attention a few months after it is built to correct minor defects. If a door sticks, try a little soap on the place that binds before you send for the carpenter. In building, don't forget to include built-in china bathroom fixtures. Tile fixtures are apt to craze. Have the electric light for your mirror front medicine closet above the closet instead of having two lights, one at each side. Provide a clothes chute to the laundry. Ours is in a corner of the linen closet. If you expect to have two cars, some day, don't build a one-car garage. Provide closets in the cellar for a million things. Have a switch plate at the head of the cellar stairs that shows red when the cellar light is on. Don't have clothes poles in your closets too thick to hold garment hangers (we did). Have a telephone extension run to your bedroom. Don't darken your windows with a porch. Make a friend of the tax assessor. One of the things you don't need to include in your new home, just to please me, is: A floor buzzer under the dining room table which your wife can never find without giving an imitation of a hostess about to have a paralytic stroke, but which a guest will find with a leg of his chair with unerring accuracy.

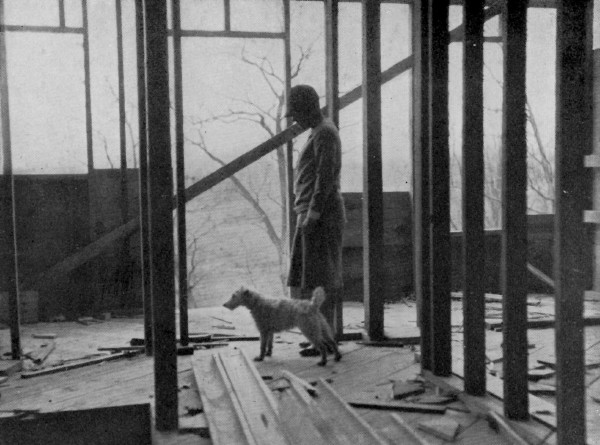

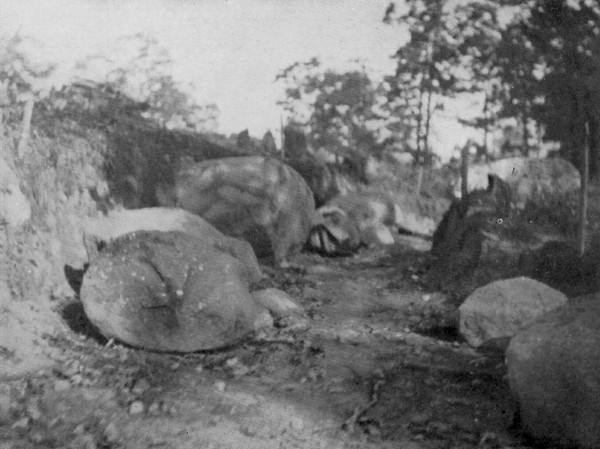

The modern way to frame a simple House using 2x4 studding. Old Houses would have huge Oak Frames morticed and tennoned together. That is why they last several hundred years. In the foreground of this picture are shown the old fashioned wooden gutters similar to those used by the colonists.  Eight months after our Foundations were started the House described in this book looked like an old landmark.   Just a suggestion of some of the Rocks encountered in digging the Cellar. The Site of this House is directly in the path of the Lateral Moraine of the great Glacier of the Ice Age.

The ideal place is never finished. Half the fun of building a home, instead of being a cuckoo bird living in a nest already built, is to plan improvements to make some day. It often happens that the thing you were sure you wanted may lose its appeal before you get it. Right now a few "some days" we are working for are:

A two-car garage with servant's quarters above. A flagpole. A chicken coop. A grape arbor. A photographic dark room in the cellar. A rose arbor. A big sugar maple tree. A canoe landing. A stone grist-mill wheel for the centre of our sunken garden. A swimming pool.

You might say that these things should be fairly easy after getting the house, and so they should, but before them must come lawns, grading, shrubbery, more tree surgery, more stone walls, more picket fences, a vegetable garden, currants, gooseberries, plums, apples, pears, quinces, rhubarb, blackberries, raspberries, and finally loads of top soil if we ever expect to have a real lawn. I was never very strong for rocks in a lawn. We have three old settlers that must be removed some day. We are a little shy of blasting since when they were digging the cellar a piece of rock as big as a football landed in the road directly in front of a car. A split-second later, and there might not have been any house to tell about. It is often as easy to dig around a rock and bury it as to blast it. You can tell a lot about the size of a buried rock by tapping it with a sledge. If it quivers and the sand rolls off it is said to "wink." That means it can be pried out with crowbars. Beware of the rock that doesn't "wink." Like the traditional iceberg in the school geography — four-fifths of its bulk or more is hidden from view. When you build any house, or plan for stone work, one of the most difficult types of labor to get is a good mason. You can get any number of so-called carpenters and painters. These seem to be among the occupations a man takes up when he isn't good for anything else. But the art of laying old-fashioned stone walls seems to have died with the advent of concrete blocks and wooden forms. The chances are that somewhere in your community there is some old codger who can do the trick. You may have some trouble to find him. Possibly he may be a Slav or Italian who did similar work in the old countree. The younger ones as a rule are no good. A real mason can size up a rock the way you appraise the snappy pair of golf stockings or sport shoes your theatre program tells you the "well-dressed man will wear." With the right mason, a few well directed blows of a hammer and a rock will split along some line of cleavage that he knew about all the time. He will shake his head in disapproval of some of the ''nice" building stones that you recommend and pick out an old relic that looks to you like a piece of roquefort cheese. If you can get your foundation stones from an old building, so much the better. Part of our house foundations came from a barn built two hundred years ago. Good building stones were plentiful then. Since then, like antiques, they have been culled over by thousands of collectors. Some of the old stones I used had been whitewashed and they crop out here and there in the wall; as much of a treasure as the patina on mahogany. I once tried to have a moss-covered stone laid in a wall. Never again. The result was appalling. First, the mason smashed his thumb in his effort not to rub off the moss. With a bandaged thumb and much profanity he had such great difficulty in handling his trowel that much of my treasured moss was covered with mortar. Finally the remaining moss unaccustomed as it was to the glare of the sun promptly curled up and died. It is apparent to me that sun-baked stones gather no moss either. A good mason always breaks joints. He never lays ''quakers" (flat stones laid on edge to look like big ones) . He never makes his mortar rich in sand to save a bag or two of cement. He can't be hired to build a wall on filled ground without a deep trench wall for foundations. He takes as much pride in his work as an artist. He realizes that it will be there long after he is gone. Like the people who dig their graves with their teeth, he builds his monuments with his own hands. No carpenter I have ever known ever said with pride, "I hung that door or shingled that roof," but I have driven miles with a mason friend of mine to see some wall or fireplace he has made. Mason work is hard work. If you don't believe it, try swinging a sixteen-pound sledge against a rock when you feel the need of more exercise. Lift a 200-pound boulder in place and hold it with one hand, while you daub mortar around it with the other, meanwhile balancing yourself on a scaffold, trying to keep your pipe lighted, and acting as though the green bottle horse-fly that is sure to light on top of your head is a welcome guest. Mason work usually seems to go slowly in comparison with other work. That is why it is good business to get good stone. Cobble-stone effects are not appropriate for old houses, although the Whitfield house at Guilford, Connecticut, has walls of stone, but they look old and have none of the smug look that we get from cobble stones pointed up with black or colored mortars. Always use white mortar if you want to be authentic. Colored mortars are a new trick of the trade. Colonial walls look as if they meant business. They never hoped to be called "pretty" any more than Pike's Peak. They were rugged old veterans built to stand the rugged climate of New England. Be sure you get the right mason. The wrong one can spoil the whole works. |