| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2012 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

| CHAPTER

IV

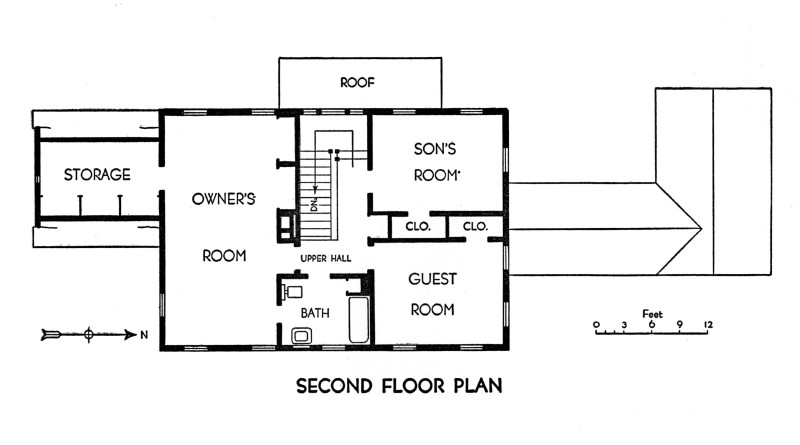

FIRST WE MAKE A PAPER MODEL MONTHS before leaving New England we had practically completed our house plans. We had studied photographs and actual examples of houses sufficiently to reach the point where the actual planning of a house started. We decided upon main foundations twenty-six feet by thirty-eight feet. This would give us a central hall eight feet wide, and a room on each side of the hall fifteen feet wide, not counting partitions. At this point the problem of the central chimney and how to keep it out of the front hall seemed to have been solved. That will be discussed later. But before committing ourselves to anything, we wanted to know how a house such as we had in mind would actually look. No houses I had seen were just like it. They were merely inspirations. I doubt whether there is a house anywhere just like the one we built. There are many, however, that contain many of its features.

Blue

prints are always

unsatisfactory in giving an adequate picture of a house. I felt that

if I could make a paper model to scale it would help a lot. Without

any previous experience in paper model making, I tackled it. It

proved to be some job for a nervous man, but it was such a success as

a model and had so much to do with the finished house that I will

describe it at length.

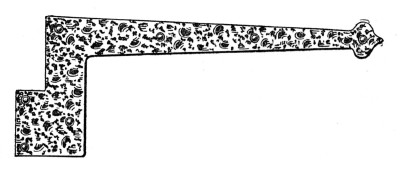

These Garage Door Hinges are 18 Inches Long. They are also left with the Black Iron Effect in Contrast with the Painted Doors.

Making this model was a fascinating experience. At times some of the detail work was irksome, but we were spurred on by the thought that it was the first step toward the house we wanted so much. I first made a rough estimate of what the final dimensions would be, including the connecting colonnade, a garage, and a sunroom. The size of the main house was determined by many houses I had measured. Many old houses are between thirty and forty feet wide and from twenty to thirty feet deep.  Photograph of the Paper Model which was made even before the House Plans were drawn. The Trees and Shrubbery are sponges dyed green. The Lawn is green Blotting Paper. The Model is made of Water-color Artist's Board. We finally decided to paint the Chimney white and black.

These are Black Iron Shutter Dogs Fastened to the House with Hand-Wrought Pins with Projecting Heads.

My dimensions overall were eighty feet. As I planned to make the model on the so-called "quarter scale" 1/4 inch would represent a foot. If you are going to tackle a model yourself, get this straight. Every foot in the house must be 1/4 inch in the model. Eighty feet therefore became twenty inches. A three foot door, seven feet high would be a 3/4 inch door, 1 3/4 inches high. The five foot chimney became 1 1/4 inches square. To make correct measurements, I secured an accurate ruler from a dealer in drawing materials. A five-cent school ruler probably would have served as well. The actual start of the model was made with a large sheet of green blotting paper, the standard kind for desks, 19 x 34 inches, glued on a board. That was my lawn. It was roughly decided where the house should stand, and leading from it to the street an entrance road was laid out twelve feet (three inches) wide. The course of this road was marked on a curve and cut out with an old razor blade. You can get a razor blade holder in the ''five and ten." Mine served for all the necessary cutting to make the entire model. In passing, let me suggest that you save this razor blade gadget. It is the world's best tool to remove paint from windows after a house is built. You can scrape the panes right up to the mullions without the slightest trouble. After the road was cut out and the blotting paper removed, the exposed board was given a coat of shellac and sprinkled with sand. The shellac held the sand in place and made a perfect illusion of a roadway through the lawn. Trees and shrubbery were made by ten-cent sponges dyed green with Easter-egg dyes and mounted on tiny twigs. They looked almost like the real thing in miniature. An artist could dab spots of color here and then on the sponges and create the effect of flowering shrubs, but I was content merely with various shades of green. Besides that, my efforts in landscape gardening had been so intriguing, (every author is entitled to use this overworked word once) that I was r'aring to go at the house itself.

These are Shutter or Blind Hinges. They are Fastened with Wrought-Iron Nails with Projecting Nail Heads.

Making the actual model was a lot of work but it was also so much fun that I was really sorry when it was finished. It also required more patience than I thought I possessed. Anyone with a smattering of what this description is all about should be able to make a paper house model that will give a far better idea of any house than a blue print or even a perspective drawing. The house model itself was constructed of heavy, rough-surfaced artists' board, the kind they sell in art stores for water color addicts. It is pretty expensive but you don't need much of it. To make the model, I first figured the height of the sides of the house. There was no allowance made for foundations because old houses were usually placed to appear as if built right on the ground. They look as if they had sprung up like a mushroom. They were almost never jacked up on high foundations in 1750. The concrete block hadn't arrived yet. I allowed eight feet for the first floor ceiling, seven feet for the second floor and a foot between floors or sixteen feet in all. That was four inches in my quarter scale. The main house was to be thirty-eight feet long, or 9 1/2 inches. Each of the wings, garage, connecting porch and sun room was made separately. When finished the whole thing was glued together. For the front of the main house I carefully ruled a rectangle 4 inches by 9 1/2 inches and cut it out with my trusty blade. Another was made exactly the same size for the back. The ends were not quite so simple. They had to include the pitch of the roof. According to my dimensions, they should be twenty-eight feet (seven inches) wide, but as I planned to lap the front and back on the two ends, I had to allow for double the thickness of the artists' board. This proved, by measurement, to be a scant quarter inch. Therefore the house ends were cut 6 3/4 inches wide. The height at the corners (the so-called posts of a finished house) were the same as the front and back, sixteen feet. Above that was the triangle or gable end which would form the pitch of the roof. After finding various centres and things and marking them with a lead pencil, I laid out a roof pitch that was exactly a right angle or 90°. This is the carpenter's, so-called, square pitch. When I ruled this and made some experimental pieces, the roof appeared too steep for a squatty house, so I cut down the height of my peak 1 1/2 feet (3/8 of an inch). It looked O.K. By measurement, I found that I should still have more than seven feet headroom in the attic. That was sufficient as we did not plan to make use of the attic anyway, and wasps and bats ought to be satisfied with seven foot headroom. On the sides and ends I then laid out windows and doors. That is a tedious job. Have your eraser handy. There are thirty-seven windows in this house, most of them with twenty-four lights or panes. I was pretty well fed up ruling windows before the job was complete. At times came the haunting suspicion that maybe nice big plate glass panes wouldn't be so bad either, but the spirit of John Alden hovered near, and like Shadrach, Meshack and Abednego, I came through the fiery ordeal without the smell of fire on my garments. Windows and doors were outlined in pencil. Then there were thirty-seven pairs of wooden shutters to make, cut out of the drawing board, painted green, ruled to look like shutters and glued in place. They looked for all the world like the real thing, strap hinges, iron shutter dogs, crescents and everything. It would have been possible to have cut out each window opening to make the illusion even more complete. A piece of glassine paper, ruled with mullions could have been glued on the back of each opening, and a small electric bulb would light up the model at night. Cutting out the windows, in addition to all the other necessary work incidental to making the model, seemed more of a job for anyone but a direct descendant of Job to tackle. But if you have enough patience to eat shad, you might get away with it and cut out each window. The lead pencil drawing was all done before I did any tinting. A faint wash of blue made the windows look more real. A little gray gave the roof a weathered look. Anyone with a knowledge of painting could get some wonderful effects. The only thing I had ever painted before was a row-boat. When the house was ready to glue together and assemble, to make the corners more secure, I first glued little strips of wood at the angles. The woodpile did not seem to reveal the kind of strips I wanted, but the frame of a ten cent kite proved to be just the thing. These frequent references to the "five and ten" may make you think that this is really a description of helping to build the Woolworth Tower. The fact is, however, that practically everything you need for a house model, water colors, glue, shellac, razor blade holder, blotting paper, ruler, sponges, dyes, even the kite, can be secured from our genial friend, Mr. Woolworth. The chimney was simply a little box. I really made two chimneys, one white with a black top and the other ruled and painted red to imitate brick. We tried both. The black and white one ultimately won. It is the only one I should consider in a house of this type. Making a house model is like playing croquet or ping pong. If you don't like it, don't do it. It can either be a pleasant experience or a bore. That is up to you. But when the model was completed it thrilled us to see our future home there in miniature, almost as it was finally destined to look. In the twilight we could almost forget that it was still a dream and in our fancy could picture the bluebirds nesting in the birdhouses and the June breezes murmuring in the trees. When I returned from a hot hard day in the city I could imagine my two little doggies running out to greet me telling me how many cats they had chased that day. Once I thought I could almost smell the lilacs in the dooryard, but I afterwards discovered my mistake. That was the glue. The little model settled for us the question whether we really wanted such a house. Everything connected with building the model is now a pleasant recollection. At that time, Heaven spared us from visualizing the bills that were to follow when the house itself was completed. |