|

Click

here to return to

A Great Year of Our Lives At the Old Squire's Content Page Return to the Previous Chapter |

|

CHAPTER XXVII

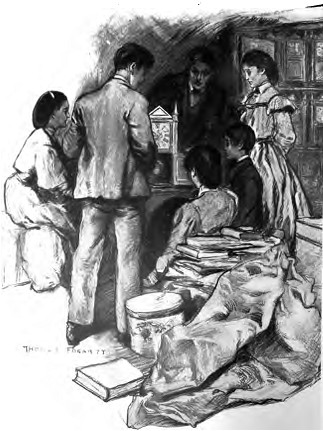

THE OLD SQUIRE'S CLOCKS THANKSGIVING DAY came the following week November 23rd, I think; and our long anticipated winter school, with Master Pierson again, was to begin on the Monday after. The year had rolled round. It had brought us its touch of sadness, also its eager new hopes and ambitions. There was the vacant chair at table, the bright little face absent forever; but the faces of us who remained were now keenly set toward the future. It was my second Thanksgiving at the Old Squire's. The first was at the time of the great snow-storm, when we got lost at Stoss Pond and were out all night as related in book first of this series. This second Thanksgiving was quite a different occasion, marked by a curious incident and not a little excitement at table. To describe it properly, however, I must revert to a circumstance which I forgot to speak of in its proper place. For three generations the old farmhouse garret had been a dim and dusty repository of cast-off articles, and offered a fine field for rummage and discovery, particularly on rainy days. Hung up there were old surtouts, faded blue army overcoats and caps, and still older poke bonnets and hats. There were two old "wheels" for wool "rolls" and a smaller one for flax, "swifts" for winding yarn, a large wooden loom for home-made cloth and blankets, and another for rag carpets. There were saddles and brass-mounted harness, and andirons with big round brass heads; old cradles, bread-troughs and wooden trays; three tall German silver candlesticks and six old whale-oil lamps; a Springfield army rifle and haversack, and a much older "Queen's Arm," with a wooden cartridge-box hanging from the trigger-guard. Then, too, there were dusty chests, a dozen or more of them, pushed back under the eaves, some containing leather-covered books, Bibles, hymn-books, sermons, files of the Pine State News, and many copies of the once popular Columbian Magazine. Indeed, I could hardly more than begin to enumerate all there was in that garret; but I must not forget "Old Uncle Ansel," as we called it, a curious combination of fly-wheels, balance-wheels, tubes and other nondescript gear, set in an oak frame as large as a large table. This odd contrivance stood for the effort of one of the Old Squire's uncles, back in 1830, to solve the then fascinating problem of perpetual motion. It was a disagreeable bit of family history, and there was some sort of queer occurrence connected with it, of which the old people were disinclined to speak. On wet days we used to steal away up there to pore over the stories in those old Columbian Magazines; and Theodora and Ellen were accustomed to time their stay when they knew that Gram could not spare them long down-stairs by giving "Old Uncle Ansel" a whirl as they read. A smart twirl of the fly-wheel would cause the machine to revolve silently for almost exactly seven minutes, and two twirls stood for about a quarter of an hour. By the time we had been at the farm a year, there was not much in that garret which we had not investigated with one exception. At the farther end of it, the end next to the kitchen ell, there was a small, low room, partitioned off by itself, like a large closet, although otherwise the garret was all one large loft, extending back under the eaves of the house on both sides, but having two small windows at each end. The door of this little room was secured by a padlock. There was no peeping in at a keyhole; nor could we boys come round on the ell roof to look in at the window, for the green paper curtain was drawn close down, and there were nails over the top of the window-sashes. No one appeared to know where the key was; and whenever any of us had asked what was in there, Gram always replied, "Nothing of any consequence." But one day, when our elders had gone away, my cousin Ellen chanced to be rummaging for something or other on the top shelf of the high dresser, and knocked down a rusty key. "Now what in the world do you suppose that's the key to?" said she. Theodora was quite unable to answer that question, and they laid the key on the table, where we boys saw it when we came in from the field to our noon dinner. "That looks like a padlock key," said Addison, and he examined it for some moments. "I tell you that's the key to that closet up-garret!" he suddenly exclaimed. "Let's try it and see!" cried Ellen; and with that we all jumped up from the table and raced to the garret. For a long time our curiosity had been gathering strength concerning what was in that closed room. Gram's non-committal replies had but whetted it; and although neither she nor the Old Squire had forbidden us to unlock the door, we yet had the idea that there was something inside which, at least, they did not care to talk about. Addison arrived first, but we were all close behind when he tried the key in the padlock. The lock was rusted and started hard. The key, however, fitted it. Addison unhooked the padlock from the staple, then shoved the door open, and we all peered in. And it was a strange sight! "Clocks!" exclaimed Addison. "Only look at the clocks!" The little room was dim with dusty cobwebs, crossed and crisscrossed; but on two sides of it were tiers of shelves, one above another, three tiers high; and on all those shelves, and on yet another shelf partly under the eaves, stood small clocks, three deep on a shelf, clocks with wedge-shaped tops and little pointed spires at the front corners. "My, did you ever see so many!" cried Ellen. "All just alike, too!" she exclaimed, laughing wildly; for so many clocks standing there all mute in that dim, cobwebby room actually looked uncanny. We went in, Ellen brushing down some of the cobwebs with her kitchen apron, and began counting those clocks. There were eighty-four of them all of the same size and just alike, down to the figure of Father Time, painted on the glass of the little front door. "Now where do you suppose they all came from?" exclaimed Halstead. "And what makes Gram keep them hidden away up here?" said Ellen. "She has never told us a word about them," Doad chimed in. "She always said, 'Nothing of any consequence in there.' Why, we might have a clock in each of our rooms!" "It is queer about them, and no mistake," remarked Addison. "I guess the Old Squire must have robbed a clock factory at some time," he continued laughing; but of course we all knew better than that. But eighty-four clocks! All just alike, and put away in this little garret room years and years ago, apparently. Halstead brought one of the clocks out, set it on a chest, and we looked it over. It was a pendulum clock, about two feet tall, with the key tied to the striking bell, inside the door.  THE OLD SQUIRE'S CLOCKS Addison wound it up. "New clock," said he. "It never was run any." "There's a little label here under the striker," said Halstead. "Says, 'Smith & Skillings, Worcester, Mass., 1836. Brass works. Percussion hammer. Warranted for Four Years. Price, $6.00.' " "Yes, siree!" cried Addison, again surveying the interior of the closet. "All nice, new, sitting-room clocks. Worth six dollars apiece. Jingo, this is a clock-mine!" "But we must never let Gram and the Old Squire know we have been spying here," said Theodora. "We must lock the door again and put the key back where we got it." "I suppose we had better," said Addison. "But where in the world did they ever get all these clocks?" "And never speak of them!" exclaimed Ellen. "There's some reason that we don't know about," Theodora said. "We ought not to have pried. So let's lock the closet again and put the key back on the high dresser. I think, too, that we had better say nothing about it. It is something they don't want us to know about, or they would have told us." So, after yet another wondering look inside that closet, we locked the door. Ellen put the key back where she had found it, and we said no more about it. In a way, too, Theodora was right. Those clocks had a history, and that old closet held a kind of family skeleton. Thirty-one years before, while the Old Squire was a comparatively young man, he had set off for Portland, the week before Thanksgiving, with a two-horse load of dressed poultry, turkeys, chickens and geese, which Gram had been raising and fattening during that whole season. It was understood that if she took care of the poultry, she was to have half the proceeds. There was over a ton of the poultry; and with a part of the profits the Squire was to purchase twenty yards of black silk, best quality, to make a gown, and a "fitch victorine" something like a fur shoulder-cape. He sold the poultry for more than three hundred dollars, but had to remain two nights in Portland, at the old Preble House, and while there fell in with a man named Skillings, of the firm of Smith & Skillings, Worcester, clock-makers. Skillings had recently come to Portland, and had three hundred clocks with him. The retail price was six dollars, but he offered the Old Squire a hundred and fifteen of them at three dollars apiece, and succeeded in convincing him that he could double his money on them by peddling them in the home county that winter. So instead of coming home light, with the money for the poultry, and the black silk and fitch victorine for Gram, he arrived loaded down with clocks. It is a matter of family record that Gram was not pleased, and that she met him with anything save an ovation. But the Old Squire was young and hopeful then; he expected to double his money selling those clocks. He rigged up a covered pung with a rack inside, which would carry twenty of them at a time, and began to make trips round and about the town and the adjoining towns. But times were hard. It was easier to plan selling clocks at six dollars each than actually to sell them and get the money. In fact, he was able to get rid of but twenty-three of the clocks, and some of these at five and four dollars each. Some, too, he "trusted out" for payment the following year. By spring he was sick enough of the investment; and when farm-work demanded his attention, he drew home a load of boards, constructed the closet in the attic, and stored the ninety-two clocks there till another winter, when he sold eight more. By this time the clocks had become such a sore subject between Gram and himself, and he so dreaded to fetch them down again, that he embarked in lumbering the third winter. And from that day onward, down to our time, neither he nor Gram mentioned the matter, nor so much as said clocks to each other. That closet had not been opened for twenty-nine years till we unlocked it that day! But eighty-four clocks! All just alike! It was impossible to forget them and one day, after we had begun planning to raise money for school expenses, we thought of those clocks. The idea of selling them occurred to us; and Addison and Ellen got the key again, and made another examination of the old closet. "They are such old-style clocks, and so out of fashion, I don't believe any one would buy them now," Ellen remarked. But Addison thought that they could be sold. "Brush them up, oil them, and varnish the cases, and those clocks would bring four dollars apiece," said he. "They are nice old clocks, with good works in them." "They're doing nobody any good up there, either," said Halstead. "Why, those clocks might all be ticking and doing some good in the world! And do us some good, too." "But I don't believe the Old Squire and Gram would let us have them," Theodora remarked. "Those clocks have been put away up there for some reason we don't know of." "Well, but they never go near them," urged Halstead. "Maybe they have forgotten all about them." "Oh, no, they have not!" exclaimed Ellen. "Gram knows all about those clocks and why they are there." "But perhaps they would let us have them to sell," said Addison. "I wouldn't like to ask them," said Theodora. "I wouldn't, either," said Ellen. "Well, no more would I," Addison admitted. "I don't quite know why we shouldn't, but somehow it seems a little like digging up an old grave." "Pooh! I'll ask them," said Halstead. "No, don't!" exclaimed Theodora. "No, Halse, not right out bold-faced," said Addison. "But perhaps we could bring it round easy, some time when the Old Squire is feeling real good-natured, and he and Gram are laughing over old times." "Maybe," assented Theodora, "if you were to do it just right." "Well, wait a bit," said Addison. He was the oldest and craftiest among us; and at last he and Ellen hit on a plan for broaching the subject. A day or two before Thanksgiving they two went quietly to the garret and wound up all those clocks, then with a goose feather and kerosene oil touched up the works, so that they would run. The clocks had been there so long that some of them could not be made to run at all; but they fixed up about sixty of them so that they could be started if the pendulum was given a swing. What they did next was to set twenty of them at eleven o'clock, ten more at one minute past eleven, ten more at two minutes past eleven, and all the rest at three or four minutes past eleven. At the old farm we used to have our Thanksgiving dinner at three o'clock in the afternoon. Addison's plan was to go to the garret just before we sat down to dinner, and set all those clocks going, so that by the time we had got well along with our dinner, and every one was feeling in a good and thankful mood, they would begin striking twelve, in platoons, so to speak, and keep it up. None of us knew anything about this, however, except Addison and Ellen. They had thought best to keep it quiet; for we had three of Gram's nieces visiting us that week from Philadelphia, and a girl named Molly Totherly, a distant relative, who was then attending school at Hebron Academy, about a day's drive from the old place. According to Gram's custom, the Thanksgiving dinner-table was set in the sitting-room, the largest room in the farmhouse. A door opened from it into the front hall; and after we had all been at table three-quarters of an hour, and the turkey was well disposed of and the plum pudding was brought on, Ellen suddenly exclaimed against the heat of the room. "Do, please, grandmother, let's have the door into the hall open," she said. "Why, yes, child, if you are too warm," replied the old lady. So up rose Ellen and set the door wide open. Addison had already left the door to the attic stairs ajar. The plum pudding followed the turkey, as usual; the mince pie was being handed round, and Gram was beaming on her company, and the Old Squire was turning a joke on former dinners at the farm, when suddenly a horological commotion broke loose in the garret! Twenty clocks, all starting in to strike at once, raised a tremendous tintinnabulation. Everybody at the dinner-table save Addison and Ellen sat up in astonishment. Dong! dong! dong! Ding! ding! ding! Dang! dang! dang! on as many different keys, with new ones breaking in! The Old Squire's hearing was not what it had once been. He looked first one way, then another, and then out of the window. "Seems to me I hear music," said he. "Where is it? Has anybody hired a brass band?" But Gram exclaimed, "For mercy's sake, what ails the clock?" There came a little lull, but immediately the next platoon opened on yet a different key, some striking fast, some slow. "Appear to have lost the tune!" the Squire remarked, with his hand up to his best ear. "Joseph!" Gram exclaimed, severely. "That's clocks striking. Can't you hear? And it isn't the kitchen clock," she added, with a perplexed look. By that time Molly Totherly and Halse were up from the table and out in the hall, investigating; the rest of us sat spellbound. For by this time platoon number three had got at it: Cling! cling! cling! Clong! clong! clong! Clung! clung! clung! The nieces from Philadelphia were amazed; but Addison and Ellen now jumped up from the table, to keep from shouting with laughter. Halstead and Theodora ran up-stairs, then came rushing down again. "It is in that old closet, up-garret!" Halse cried. "Sounds as if more than fifty clocks were striking at once in there!" for all the rest had now started in, as if executing a grand finale, for which the previous efforts had been merely the overture! But no sooner had Gram heard the word garret than she turned quite pale. The Old Squire was out in the hall. But Theodora came hastily round to the back of Gram's chair. "No, no!" she whispered in her ear. "It is just one of Ad's pranks," at which the old lady sat up. "Oh, the rogue!" she cried, and then she began to laugh, and laughed till she was breathless. "Come back here, father!" she finally called to Gramp. "They have found your load of clocks at last." The Old Squire returned to the table, looking a little queer. "We found them almost by accident," Theodora explained, hurriedly. "We didn't really mean to pry into anything," "But do tell us, Gram, how there came to be so many of them!" cried Ellen. "Oh, that isn't for me to tell!" cried the old lady, airily. "They are not my clocks. You will have to ask your grandfather about that." "Oh, tell us, Gramp!" Ellen exclaimed. Never had we seen the Old Squire so embarrassed; he looked actually sheepish. "You will have to tell them now, Joseph!" cried Gram, exultantly. "You will have to own up to those clocks now!" She fell to laughing again. But he would not enter on the subject at much length. "Oh, I took a consignment of clocks off a man's hands once," said he, in an offhand tone. "They didn't sell quite as well as I thought they might. And those you saw up-stairs were some I had left over." "Yes," said Gram, with intense irony. "Just a few clocks left over! That's all! Just a few!" and she relapsed into another fit of laughter. Clearly, she considered that the Old Squire's description of the transaction was wholly inadequate. But here Addison, who had been watching his chance, put in a word. "Those are pretty good clocks," he remarked. "They're a little out of style, but I think I could sell them. What will you take for the lot, sir?" "Before there's any trading done," said Gram, "I want to say that I've got a black silk dress and a set of furs sunk somewhere in those clocks." "Yes, yes, Ruth, that's so, that's so," replied the Old Squire, hastily. "You shall have all that the clocks bring." With that, Addison addressed himself more particularly to Gram. "What do you say, Gram, to about a dollar apiece for those clocks?" But she had dealt with too many tin pedlers in her day to be caught napping. "That's not enough," she said. "But as it is all in the family, Addison, if you will promise me a hundred dollars out of it, you may have them and no more said." Addison hastily consulted with Ellen and the rest of us. We all went up-stairs and looked again at the clocks. It seemed a promising speculation; so we wound up that Thanksgiving dinner with a bargain for the Old Squire's clocks, all amid much laughter on the part of our guests as well as ourselves. I may add here that as far as we young folks were concerned, it was well that we had our laugh at the time and made sure of it. For we never had a chance afterwards to laugh much over the outcome of that clock speculation. If anything, we fared worse with those clocks than the Old Squire had, thirty years previously. Bad fortune seemed destined to go with them; but that is part of another experience which runs far ahead of the limits of this volume. While yet we lingered at table, bargaining for the clocks, Thomas and Catherine came jingling to the door in a new sleigh with Tom's colt. They had had their Thanksgiving dinner in advance of us and driven to the post office for the mail. They brought a letter for Addison from Master Pierson and came in to hear it read, for they were quite as eager as we to learn what "Old Joel" had to say. His letter put even those clocks out of mind. "Hullo, all you young Latinites up there!" (That was the way it began.) "How's Ζsop's Fables? How's Cζsar and the Helvetii? How's Ariovistus rex Germanorum? Have you forgotten all you learned last winter? Did the mumps ump it all out of your heads? Better be brushing up and reviewing from now till Monday. Catch your breaths and get ready, because this winter I am just going to make you all everlastingly pick up and hiper! So be all ready to pitch in and not waste a minute. We will have a Quiz on Latin to start with. I'm going to put you through four Books of Cζsar this winter. So get ready to do some tall studying, evenings. "Tell 'Mother Ruth' to get the burlap down on the sitting-room carpet." "My sakes," muttered Gram. "If this Latin business goes on another winter, I will have to buy a new carpet for that room." "Ask the Old Squire how his 'Constitution' is holding out," Joel's letter ran on. "Ask him if the 'Monroe Doctrine' is still in force up that way? Tell him to have a writ of 'Habeas Corpus' ready to get me out of jail on, if I should happen to have a difficulty with School Agent Tibbetts. And, by the way, how is Old Toddy-Blossom's health this fall? Pretty quiet, isn't he, since that little episode of the County Attorney's letter which he opened? Not quite so rampant as he was at school meeting last spring? Nothing so quieting, sometimes, as a little wholesome fear. Particularly with a rum-seller. One like Tibbetts who knows he is doing wrong and injuring everybody. That's the worst kind of a sinner the fellow who knows he is doing wrong and keeps at it. "I tell you boys, that is the one thing you can't live in peace and harmony with rum, intoxicants. I defy you to. It demoralizes everything, puts everything wrong, drags the whole neighborhood down hill. You cannot have peace with it. You've got to fight it." "Good!" exclaimed Gram. "That's just right!" "That reminds me," the letter continued. "Tell that Alfred Batchelder, if it comes handy, that I've got a bigger stick than I had last winter. Also verbum sap. if he learned Latin enough to know what that means." "I don't believe he did," Catherine remarked, laughing. "That will be thrown away on Alfred." "Say to Halstead, too, that I am very much in earnest to have him start with right ideas this winter," the letter went on. "He had wrong notions in his head last winter, and they did him a whole lot of harm. I want to have the school amount to something to him this winter." "O, shucks!" Halse exclaimed. "Old Joel's got only one idea in his head, and that is, study, study, study! For my part I want a little fun as I go along." "That depends on what a fellow calls 'fun,' "Thomas remarked. "For my part I thought we had plenty of fun last winter." "You call Latin fun, I suppose!" Halse retorted. "The way we took it, yes, pretty good fun," said Thomas. "It made us work, but we got lots of fun out of it; and somehow it made us feel as if we were getting on in the world and were going to be somebody." "Oh, you think you are going to be 'somebody,' do you?" said Halse, sarcastically. "I don't know yet, and you don't," Tom rejoined, laughing. Not relishing this sort of conversation Catherine interrupted it to ask Addison if that were all of Master Pierson's letter. "No," said Ad and resumed, smiling broadly: "Tell Round Head" (this humble chronicler) "that I've got to rub his ears for him again and wake him up. He hasn't really waked up, yet. He doesn't seem to know what he is in the world for. But tell him that I'm going to wake him up, this winter, or I will wear his ears out. What he needs is to make up his mind what he wants to do in the world, so as to go about it and feel certain of something." It wasn't easy for me to see the joke in this, nor understand why the others laughed. It is said there are persons who never do really wake up to life and its actualities. I have often feared that I was one of that kind. "Remember me to 'Sister' Theodora and to 'Sister' Ellen and 'Sister' Catherine," Joel's letter concluded. "I never had any sisters of my own, you know, and I never knew what I had missed by it till I boarded there at the Old Squire's so long. A fellow really does need sisters. Sisters are a great institution. So I've concluded to adopt all three of them if they can put up with such a brother. And anyhow they will have hard work to shake me off!" The girls looked at each other and laughed. Jocose as was the compliment, it pleased them immensely. "Look for me Sunday afternoon," the letter ended, "with the old melodeon, all the old maps and books, and a few new ones. Vale. Selah. Yours for school, "JOEL." That was Joel, dear old Joel, Joel all over; the best schoolmaster we ever had. THE END OF BOOK SECOND.

|

Web and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio

1999-2008

(Return to Web Text-ures)