| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2009 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click

Here to return to

A Great Year of Our Lives At the Old Squire's Content Page Return to the Previous Chapter |

(HOME)

|

|

CHAPTER XXVI

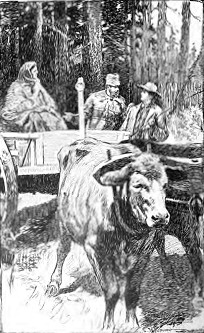

MY RIDE WITH MARY INEZ FOUR or five days later, after we had finished our task of cutting the hop-poles, I had a curious adventure, of a somewhat similar nature to that just recorded. Of the Old Squire's lumber camp on Lurvey's Stream, up in the Great Woods, I have already spoken. The loggers had now gone there for their winter's work, cutting spruce; and if the snow had come and laid, as the weather during the first of the month seemed to promise, the teams for hauling the lumber would have been sent up there before this time, and taken their grain for the winter, also the food supply for the men. But there came a week or more of warm clays — a kind of belated Indian summer — which carried off what little snow had fallen earlier in the month. Hungry loggers who work hard consume rations rapidly; and on the evening of the 13th word was sent down to us at the farm that the camp was running short of food. The stores were already bought and put up, waiting to go with the teams and sleds; but as the weather continued soft, with the ground still bare, the Old Squire sent me off, next morning, with one yoke of oxen and the two-wheeled cart, to pick my way up to camp, and haul a load of supplies. The distance was nearly twenty miles, much of the way through the woods; and as oxen are slow, a day was required for the journey to the camp, and another to return home. The road was about as bad as a road can be — a mere trail, never much used till after snow came. I had three bushels of white beans, two barrels of pork, a barrel of flour, a ten-gallon keg of molasses, four bushels of Indian meal in two bags, a two-gallon keg of vinegar, two barrels of cooking apples and one of eating apples, four bushels of potatoes, four of turnips, half a barrel of sugar, two boxes of salt, and some other articles, besides half a dozen axes, three peevies and two steel wedges — altogether about a ton in weight, but well packed in the cart body and securely lashed on account of the rough road. It was not deemed a hazardous trip for me. Old Bright and Broad were used to carting. They were two eight-year-old Durham cattle, seven feet and four inches in girth, and steady as clocks. However rough the road, they could be depended on to move calmly and slowly. In fact, they were rather too slow; two miles an hour was about their natural rate of travel, unless they were hastened with the goad. I was given an early start from home, stopping only for a half-hour to bait by the roadside. I reached the camp just at dusk, and was hailed with delight by the eighteen loggers there. In prudence, I should have started on my return trip before sunrise the next morning; but after breakfast I was tempted to go off with two of the younger loggers to see a beaver house at a pond in a stream, some distance from camp. We lay in wait here for two hours, hoping to get sight of the beavers: and with one delay and another, it was noon before I yoked my team and made a start. I now found that I was to have a passenger in the cart, the wife of one of the loggers, who had come up to the camp on foot during the forenoon from their house, fourteen miles below, to bring her laboring husband his winter supply of socks and knit leggings. As there was no place for her to stay overnight, she had to return that afternoon; and as she was tired from her long walk, I could do no less than offer her transportation, if she deemed riding in the cart over that rough road easier than walking — a subject for doubt.  She decided to ride, and her husband, having found a half-barrel for her to sit on, asked me to drive very carefully. The affectionate manner in which he then took leave of his dear "Mary Inez" — as he frequently called her — impressed my youthful mind with a high sense of her preciousness. We had not proceeded far when we began to have music. The previous morning some one, whose duty it was, had forgotten to "grease the cart," that is, to lubricate the large wooden axle of the wheels. It had not run dry during the outward trip; but now it began to call out piercingly for grease. The massive wheels had great wooden fellies and huge hubs, such as the pioneer wheelwright was accustomed to hew out fifty years ago. The axle, or "ex," as the farmers called it, required frequent applications of lard. I knew very well what the matter was. But there was no help for it now, so I drove on. There was no danger that the wooden axle would heat or choke, but the sounds that issued from it were horrible. Groo-ooo-oo-eee-ew-ew-aw-oook! Groo-ooo-oo-eee-ew-ew-aw-oook! at every revolution. It soon became about as much as the human ear could endure. I had driven slowly to spare my passenger the jolts. But the sky had been growing overcast since morning, and now the certainty of rain led me to hasten our progress with the goad. This proved rash, for immediately an unusually hard jounce over a log threw the woman off her seat. Falling forward, she struck her nose on the rail of the cart body, with the result that the blood began to flow. She got out of the cart and sat down on a stone, and a very distressful interval followed. About all I could do for her was to fetch cold water in my bucket from a rill at a distance, and then look on. It seemed to me that she must surely bleed to death. The hemorrhage continued for nearly an hour. I thought it would never stop, and was filled with panic. If she bled to death there, I was afraid that her husband might accuse me of maltreating her, for I felt a little guilty because I had driven the cart so fast. The flow of blood stopped at last, and looking very pale and dishevelled, the woman got into the cart again. The oxen, meanwhile, had lain down in the yoke, and were chewing their cuds. We went on. But it was not long before sleet began to fall, the beginning of one of those southerly storms which in that part of the country often come on in the afternoon, increasing in violence during the evening and night. Evening, in fact, was at hand, for at this season of the year the afternoons are short. Passing an opening where several haystacks had been put up for the lumber camps, I stopped, and bringing large armfuls of the hay, piled it high about my passenger's seat, to keep Mary Inez from bumping her precious nose again. As the wayside was very brushy, I now took up my own position on the cart tongue, where I could hold on by the "sword" at the front end of the cart body, and hastened old Bright and Broad on with frequent pricks from my goad. At best, however, we could proceed only at a walk — and with every turn of the wheels that long, loud and dismal Groo-ooo-oo-eee-ew-ew-aw-oook! went echoing through the forest. Cloudy nights in November are always very dark, but I do not believe that ever a darker one than this descended. I had a whale-oil lantern, which we always carried when out with a team; and lighting it, I tied it by the ring to the top of the sword, whence it cast a feeble light on the backs of the oxen and on the wan face of my passenger in the cart. We went squeaking and bumping on our way for two or three miles more, the oxen keeping the road from an instinct which cattle have, rather than from sense of sight. Owls hooted, as they often do before storms; and once the oxen stopped short and were very reluctant to go on, probably from scenting a bear in the road ahead. Shortly afterward we forded a brook, and then the woman knew where we were. "'Tis three miles from here home. We'll soon be there," said she, and became more cheerful. She had been anxious concerning her three small children, left in the care of their grandfather, an old hunter and Maine woods guide. But the worst of our adventures was still to come. As we plodded up the ascending ground beyond the brook, I heard a loud snort behind us, and above the squeaking of the cart caught the sound of hoofs splashing through the brook. Somebody's coming!" exclaimed the woman. Indeed, my first thought was that a man on horseback was galloping after us, although to gallop a horse over such a road in such darkness would have been a feat worthy of The Wild Huntsman himself. In a moment the sounds of galloping came close up behind us, and I shouted, "Hello, there! Wait a bit and I'll turn out!" and jumped down to execute the promise. But with another wild snort of his horse, the rider turned and went galloping back down the hill to the brook and across it. "My goodness!" cried the woman. "He must be crazy!" I thought so, too; moreover, I was mystified, and began to be frightened. Another snort far back along the road blended with the creak and groan of our axle, then more galloping; and again the wild rider came close up behind us! Again I shouted, "Hello, there! Who are you? What do you want? Do you want to go by? If you want to go by, say so." The only response was another snort and another mad gallop back along the road. "I caught a glimpse of something!" said the woman, in an awestruck whisper. "It looked like an old stump — as if he was carrying an old stump over his head!" This was far from lucid or explanatory. I had discerned nothing myself. The glimmer of the lantern was a little nearer my face than that of my passenger and prevented my seeing. A chill stole over me — fear, no doubt. The oxen, too, were hurrying forward at an unusual rate. One of them gave vent to low mooing sounds. We had gone on but a few rods, however, when our strange pursuer rushed after us yet again at a furious gallop, as if to ride us down, and came up to the very tail-board of the cart. Once more I shouted, "Hello, there! What's wanted, anyhow? Are you trying to get by us?" Again it wheeled, snorting. Mary Inez screamed outright, then hid in the hay. "Oh, I saw that stump again!" she cried. But I saw nothing. The thing galloped away, but instead of going back far, plunged into the woods to the right of the road. We heard it go tearing through the fir growth, crash on crash. The sounds moved past us, describing a circuit through the woods, then crossed the road ahead, came completely round us on the left, and approached from the rear again. I now felt sure that no human being was concerned in the demonstration, since a man could hardly ride a horse at such a rate through thick woods. A suspicion as to what it was began to dawn in my mind. Meanwhile the oxen had been hurrying on at a great rate, and presently we heard some one shout, and saw through the storm the glimmer of a lantern in the road ahead. "That's father!" cried the woman. "We're most home!" and she called out joyfully. As she surmised, it proved to be her father, Jared Robbins, who had heard the distressful squeaking of my wheels, and guessing that his daughter might be with me, had come forth to meet her. When we told him that we were being followed by some prodigious beast, the old guide at once confirmed my suspicion as to what it was. "That 'ere's a moose!" said he. "He heerd your cart ex creaking, and he thought 'twas another moose, a cow moose, bawlin'! I don't wonder. I vum, I thought 'twas one myself when I heerd ye comin'! "Now put out your light," the old man continued, in some little excitement. "Put out your light and I'll put out mine. Then you drive on slow and let her creak, while I hiper back to the house and git my rifle." The old man hastened away. And getting down from my perch on the cart tongue, I drove slowly into the opening where their house stood. Robbins soon came out with his gun; but although we heard the moose snort several times at a distance, the animal did not approach the cart again. It was now about nine o'clock, and owing to the storm, I decided to remain there for the night. Before morning the sleet had changed to snow, as much as five inches having fallen. So inclement was the day that I was in no haste to set off. But the old woodsman, Robbins, had risen and gone out at daybreak to hunt the moose. He tracked the animal to a swamp some two miles away, and getting sight of it here amidst the snowy boughs of a thicket of young firs, brought it to the ground with his first shot. He returned in great good humor; and after Mary Inez had prepared breakfast, I yoked my oxen, and going with the old man to the swamp, hauled the moose to the house. It had a fine spreading set of antlers — probably the "old stump" which my passenger had seen. While I was assisting Robbins to hang up the carcass and dress it, a messenger from home, in the person of Addison, arrived in quest of me, riding one of the farm horses. The family had become alarmed for my safety, and had sent Addison to look me up. We were all the afternoon getting down to the farm, six miles, but had a quarter of moose meat to show for my adventure. |